“We’re trying to uphold a delicate state of anarchy. Anarchy in Egypt”: The incredible story of The Grateful Dead’s legendary gigs at the Pyramids Of Giza

In 1978, The Grateful Dead and their entourage landed in Egypt for three gigs at the Pyramids of Giza. This is what happened

In late 1978, The Grateful Dead made history by playing three shows at the Pyramids of Giza, accompanied by acid guru Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters. Journalist Max Bell was there to witness the magic and the madness unfold.

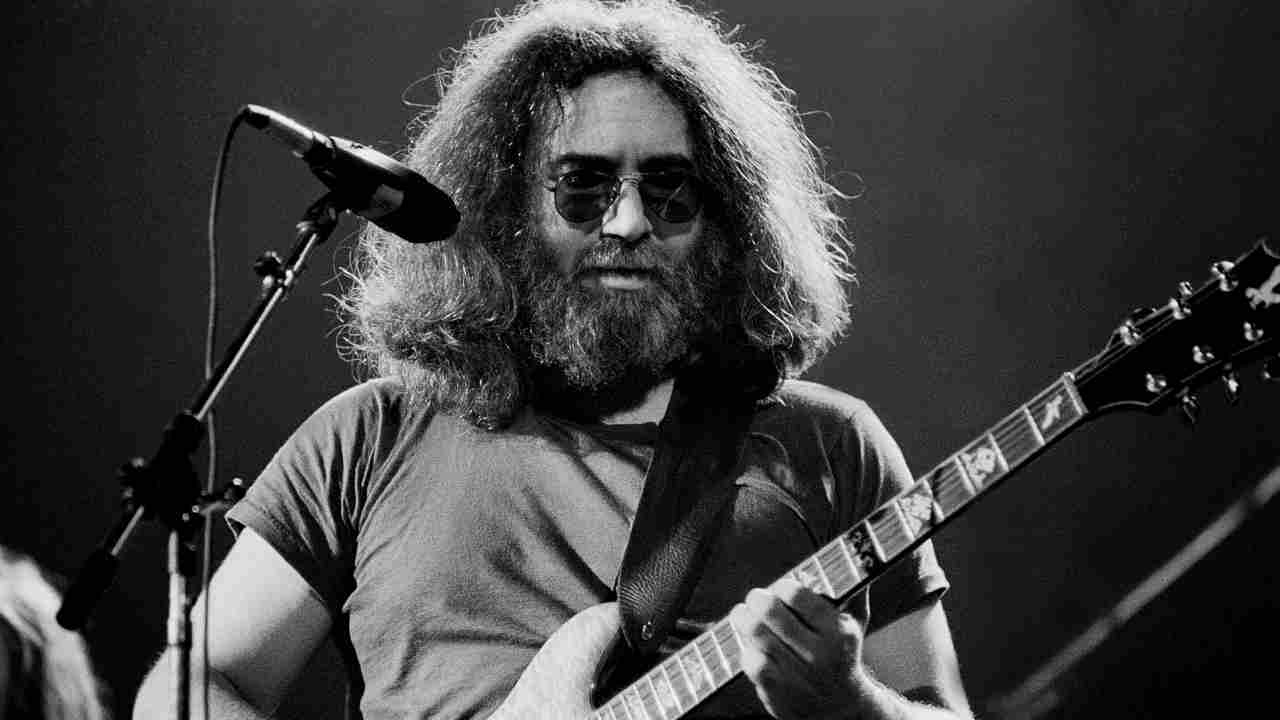

Cairo, Egypt. September 16, 1978 – a date on which, in the evening, there will be a total eclipse of the full moon. Grateful Dead head Jerry Garcia is standing on the Sound and Light stage that has been built in the desert at El-Giza, overlooked by what remains of one of the ancient Seven Wonders Of The World.

“You’re asking me whether the Grateful Dead still represents the ideals of the 60s?” he says. “No, we don’t. We’re trying to uphold something else today. Not so much idealism, more a delicate state of anarchy: anarchy in the USA, I guess. And now – anarchy in Egypt. Coming here’s a dream we’ve had for a long time and the Pranksters are here too, which is great. It’s been a long time since we hooked up with Kesey. This is like the Grateful Dead’s first annual pyramid prank. I love it. God knows how we’ve managed to actually get here. Heh heh. Allah be praised.”

A few days earlier outside Cairo International Airport, at 4am, two guys from the British rock press, one photographer and a distraught Arista Records representative are looking for somewhere to sleep. The Egyptian government officer who’s meant to be meeting the party isn’t here and their hotel reservations don’t exist. We disappear into the rising dawn, the sun spilling orange across the desert. It’s going to be another hot one in a freak heatwave that sees midday temperatures reach a skin-blistering 46 degrees centigrade.

Arista man and the duo from Melody Maker opt for a cushy Sheridan in downtown Cairo. Me and my friend Tim, who has shut his central London record store to “see the old hippies again”, book into a cheap flophouse on the edge of the Eastern Desert, in full view of the three pyramids. The room’s a cupboard with a shower that doesn’t work, and a TV that does, when kicked.

After no sleep it’s time to investigate; time to brave the six-lane superhighway and dive between the donkeys and diesel lorries into the city. Cairo is where the Occident meets the Orient. But the Egyptian has no love for deadline. His watchword is ‘baksheesh effendi’ and the local pound goes a long way, given the poverty of an environment that has evolved over 5,000 years. As Herodotus remarked: ‘Egypt is the gift of the Nile.’ And it’s a gift that keeps on giving. Striped djellabas [robes] are purchased to ward off the heat and mosquitos in a bazaar where Coptics, Jews, Christians and Muslims exist in a sensory cauldron.

In the ghetto of the City of the Dead the lepers – the untouchables – lie in leprous discomfort. But it’s cooler in the medieval market, where you swap stories with the juice bar guy and share a hookah. Smoking hashish is tolerated, so you squat in the dirt while the Bedouin splits his stash from the Lebanon and cuts up chandu for the water pipe. “Hubble-bubble is good, yes? Smoke him, then you forget.” Indeed you do.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

A world away from the market and the mosques a crowd of long-haired Americans is congregating in the coffee shop of the Mena House hotel in Oberoi. This ornate edifice isn’t the real Egypt, rather a haven for the rich tourist who doesn’t mind the sight of Armalite wielding guards and the military Jeeps touring the barbed wire perimeter. Israel and Egypt have been locked in endless conflict but are on the verge of a historic peace treaty. Bombs have gone off in Cairo all year and the REAF [Royal Egyptian Air Force] runs its hardware across the sky while elderly tourists lie on silver tanning sheets by the pool while the thermometer hits 120 in the shade.

The Mena House is used to catering for wealthy visitors but they’ve never seen the likes of the Dead’s entourage spilling into the lobby. Californian dudes in cut-offs and day-glo Kelley Mouse T-shirts hold hands with ladies in jangling ethnic head dresses studded with turquoise scarabs. Away from the hubbub I notice a large figure with a substantial beard and greying black locks. Jerry Garcia, the boss man.

A waitress brings coffee, oblivious to his notoriety as Captain Trips, launcher of hallucinogenic mind travel. Dressed in a faded shirt, worn Wranglers and battered boots, Garcia pores over Philip Jose-Farmer’s The Dark Design. He lowers his shades and proffers a clumpy hand. “I was wonderin’ when you English would arrive. They treatin’ you well? Crazy place, ain’t it?” he chuckles approvingly.

Phew, we are on the case. As assignments go this is a fucking peach. The Grateful Dead’s ultimate Acid Test with Merry Pranksters in tow has been months in planning but only passed at the eleventh hour and even then, according to promoter Bill Graham, here for the ride, “Three of the sons of bitches lost their passports.”

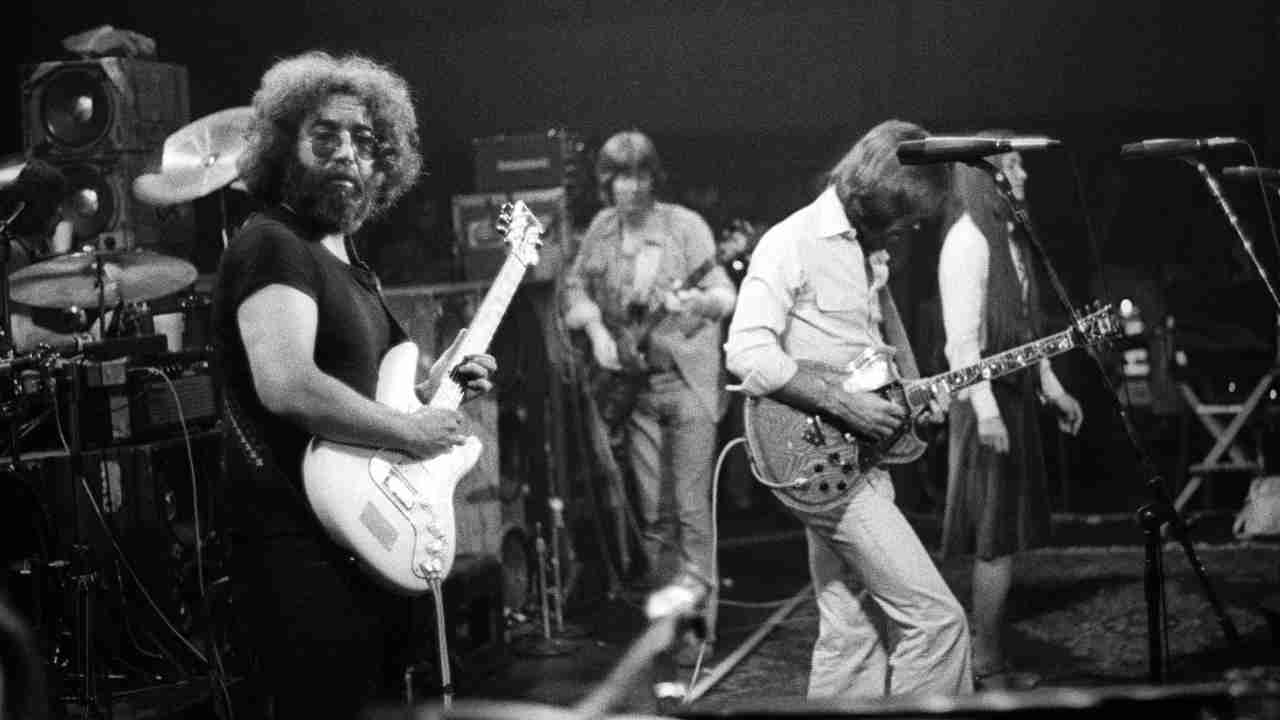

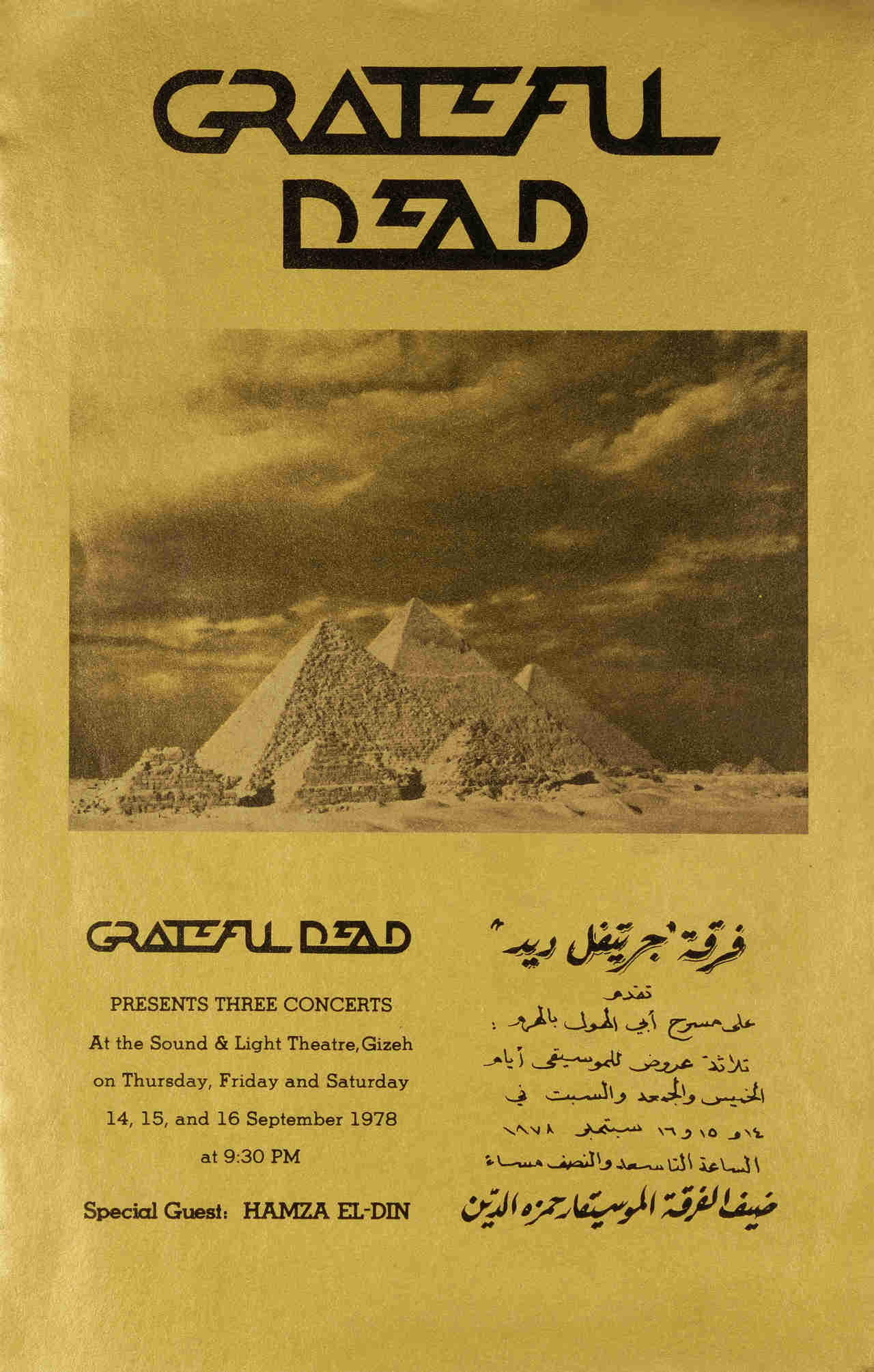

Given the fallacy that the Dead took their name from the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, this short strange trip makes weird sense. They will play in front of the last survivors of the Seven Wonders of the World: Cheops’ Great Pyramid and Kepren’s Sphinx – the woman lion – on the Son et Lumiere stage. Their sixth and final set is timed to coincide with a total eclipse of the full moon.

There’s a back story. The Grateful Dead’s Egyptian jaunt will cost the band $500,000 in advanced future royalties. Any profits go to Mrs Anward Sadat – the president’s wife – and her Faith and Hope Society for the rehabilitation of the handicapped, and a backhander to the Department of Antiquities, responsible for the maintenance of Nubian culture.

The project originally stems from a photographic assignment carried out by Grateful Dead manager Richard Loren, scouting for unusual Dead-friendly venues – Easter Island is also mentioned. Loren’s visit is blessed by the Minister for Culture so co-manager Alan Trist, Loren and bass player Phil Lesh do another rock’n’roll recce. Lesh’s discovery of the eclipse date sends him back to the band’s Marin County HQ bursting with important news. “Once that was discovered the trip became essential,” says Lesh. “Too good to miss. They got off their asses.”

The three concerts are tightly restricted to a crowd of only 1,000 a night, 300 of whom are a group of American Dead Heads who have chartered a flight out of San Francisco. Despite their notorious insularity, the visit piques the attention of NBC and CBS news crews. Rolling Stone magazine, who have ignored the Dead of late, send a writer. The British press, sucking on the full impact of punk, has to admit this is a stunt only the Dead might pull off. Give the old bozos some credit.

It’s a pleasant surprise to discover Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters amongst the mayhem, unpacking kaftans for one last out-there adventure and armed with a stash of Stanley Owsley’s legendary liquid LSD. The Pranksters have travelled from farms in Eugene, Springfield and Pleasant Hill, where Kesey’s brother Chuck runs a creamery.

When I meet Kesey by the pool he produces a manuscript, The Trial Of Neal Cassady, a biography of the Prankster Supreme. In his satchels are spools of 16mm film and tapes he wants to edit – to document the Acid Tests and the Last Whole Earth Catalogue. Gruff and hoary, Kesey has evidently taken many more drugs than I’ve had hot dinners. He looks around and points out the other Merry Pranksters to me: “Mountain Girl, the jock is George Walker. Those guys rapping are Mike Hagen and that’s Paul Krassner, editor of The Realist. That wild-looking man is Zonker. He’s brought a metal detector with him and he’s been discovering artefacts near the Sphinx. That can’t be legal!” Kesey laughs. “The missing shadow is Cassady. He’s here in spirit. Man, he would go nuts here.”

Jerry Garcia’s Presidential Suite is on the top floor of Mena House, overlooking the Great Pyramid which is reflected in his glasses. He gazes at the creation King Cheops financed by sending his daughters out whoring. The peak was encased in gold. Atop the summit a tiny figure is shinning up the spike. He slips then rights his balance to avoid a 481-foot fall. Garcia hands me a telephoto lens and shouts in triumph. “He’s done it! The brave fucker’s got the Grateful Dead flag up there!”

Yep. The ‘Laughing Jap’ skull and flash is planted for all to see. Bob Weir strolls in smoking a Winston, drawling like a Colorado cowboy. “I believe he’s gonna try and throw a Frisbee off the top, but he won’t be able to. People have attempted to clear the Pyramid with a gold ball but the wind always blows it straight back. Strange atmospherics. I’m gonna race Mickey Hart up there this afternoon. Fifty bucks says I beat the little bastard, huh Garcia?”

“I don’t know, man. Hart is wiry and he don’t smoke,” the guitarist counters. A procession flows through his room, stepping over guitars, banjos and piles of books. Not many clothes though. “I’m not fashion conscious,” he laughs. “I expect you noticed.”

Phil Lesh wanders in clutching a bottle of ale, snorting with delight at Walker’s derring-do. “You heard about Weir and Hart, Garcia? I’m betting neither fucker makes it and the road crew concur.” Lesh departs to the sanctuary of the bar where he becomes a permanent fixture with girlfriend Debra Kashmir and liberal quantities of Egyptian Estella.

Garcia locks the door and I take a good look at the man. The half stump of his right-hand middle finger reflects his demeanour. He’s solid and reassuring, commanding respect without trying.

But this Egypt trip has been soured for the band’s English fans by the cancellation of what would have been their first British engagement since Wembley Stadium, 1975. They won’t return until March 1981 at the Rainbow. “We feel bad about it and sure it’ll harm our reputation – we continually harm it. It’s a bit late to be thinking about building a career. We’ve fucked up before, but we just couldn’t afford to fly home then go to Europe. We owe Arista way too much and our next album – the work in progress Shakedown Street – has to cement our relationship. Weir’s saying we need to get practical and I agree.”

In these punked up dog days of 1978 the Dead’s failure to honour a commitment made to promoter Harvey Goldsmith has raised eyebrows. Plus Goldsmith is having a bad month. He gets Loren’s no-can-do Telex on the same day that he discovers The Who won’t be going on the road since Keith Moon has overdosed on prescription drugs in Harry Nilsson’s Mayfair flat, coincidentally on the birthday of the late Dead singer Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan. It’s a case of phuck the pharaoh for old Harve.

Any suggestion that the Dead bask in California counting their loot is greeted with hilarity by Garcia. “That is bullshit, a total misconception. We don’t have servants or lots of cars. I run a VW. We don’t accumulate money or invest in apartments or any of that crap. Some years lots of money goes through the account, other times we lose a fortune.” Garcia’s Mountain Girl, Carolyn Adams, looks up from a magazine. “They’ve lost several fortunes. They’re hopeless at finance. Especially Jerry.” Her old man smiles ruefully. “Well, thank you darlin’”.

The new wave’s desire to sweep away old timers like the Dead doesn’t faze Garcia. “That’s natural. I like the Ramones. They’re kinda funny. Speaking sociologically, punk is different in the States. In Long Island and New York it’s produced by the cultureless middle class. Musically it’s just rock’n’roll, either good or bad. I don’t believe in any other label. I mean I object to us being typecast as just a psychedelic band. We ain’t.”

Garcia fires up a Camel and Red Leb joint and considers the ongoing Shakedown Street album, some of which is previewed in Egypt. “We chose Lowell George as producer because we wanted someone who understands band dynamics, I’d rather not have a producer at all but some of the others disagree. I’m not happy with all the tracks, I never am. It’s a modest album, simple in design like American Beauty. Our last record, Terrapin Station, was spoiled by Keith Olsen and Paul Buckmaster putting on a gazillion strings and counterparts you can’t hear. Fucking unbelievable. He came in spouting minimalism and then went ape. We gave him songs with dotted shuffles and he turned them into orchestrated four beat marches. What a screw up.”

The Captain mentions a few cuts from the record, like Fire On The Mountain, influenced he says by “reggae’s rich vocal phrasing rather than syncopated bass and backwards drumming. We’ve only rehearsed that for five years,” he chuckles. “Then there’s the All New Minglewood Blues (aka Born In The Desert), which is more ancient. The title song is Dead go disco with funky rhythms. We’ve even been messing with an instrumental version of the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive. That’s a great song.”

Bob Weir is down the hallway listening to Tom Petty and Patti Smith tapes when I stagger out of Garcia’s den. There’s something of the Dead’s image-maker about Weir. He’s the least enamoured with the band’s laissez-faire attitude.

“We tend to seek out trouble,” he says. “All of us are legendary soft touches. On a good night we’re still a great live band, none better in my view. I’m aware of the constant criticism we receive for the way we construct shows and our lack of presentation. I also hear the opposite viewpoint. Sure, the solos are long but they’re shorter than they used to be. Instead of visiting three nebulous regions we now aim at a few more. I’m not always happy with the space stuff – unless the feeling is right. Before we left we played the Giants Stadium in New York City and Garcia slept through it in my opinion. It was too early for him.”

As for the Dead family, Weir, the youngest member at 30, isn’t looking to bail out. “These people are the closest thing I have to brothers, despite age old impasses which we tend to ignore. I can’t imagine how we’ve made it day to day but having got this far intimacy should keep us going.”

Even so there are ugly rumours about heavy drug use in the Dead – cocaine is now rife in the West though few are aware yet of Garcia’s heroin addiction. It’s hardly front page news to Weir of course. “Drugs are a feature and that worries me. I’m not a heavy doper, haven’t done acid in a while either. I smoke more than I should. Garcia certainly needs to take better care and get in shape but he’s a grown man. Moralising isn’t part of our psyche.”

I’ll have several more conversations with Garcia over the next few days. One recorded sitting on the Sphinx later emerges on tape as oscillating white noise, which delights the guitarist when I tell him so later on. It’s Saturday night, the eve of the eclipse. A lunar wind lifts the sand in vicious waves that sting the skin. In the hills outside Giza Bedouins form eerie caravanserais. Owls and bats swoop overhead.

Backstage I find Garcia laid out on a slab after soundcheck, sleeping like a corpse in a mortuary. When he stirs we chat. “The Mariner space probe showed that there was evidence of of pyramid shaped objects on Mars,” he cryptically remarks.

He picks out a neat country sketch on his custom Doug Irwin guitar, encrusted with mother of pearl, and lets a barely smoked cigarette burn to ash. “Just being out here in the open collecting sensory information, like that tribal chanting in the hills, is better than constructing any hypothesis about pyramid theory. I’d just like to know who we are, and how we got here. I don’t care how I find out. A lot of 60s people got high, dropped out or turned out disciplined PhDs trying to account for the wider psychedelic experience.” Garcia produces a copy of The Invisible Landscape by the brothers McKenna. “Fuckin’ weird book. It’s all about the properties of ultra violet psilocybin located in the Amazon delta. Fancy a visit? Heh heh. I sure do.”

Garcia is a subscriber to Scientific American (who will put him on their cover) and, er, The Brain News. “Fine magazine. The transition of material reveals that one as an organism is continually breaking out. Wanting to produce living elements out of rock, say, arises from the surprise element, and intelligence would rather be surprised. It’s more delightful.”

The Dead’s road crew – noisy Americans and aloof English – are scuttling around the base of Great Pyramid for tonight’s tour de force, a sonic concept fastidiously mapped out by Owsley. Cables are burrowed through tunnels into the burial chamber to produce a brain scrambling candy. Chaos theory. “It may work but knowing Owsley it may also blow up the pyramid,” Garcia smiles before returning to camp for a pre-show livener.

Out in the desert, Weir and his bosom buddy David Freiberg, ex-Quicksilver Messenger Service, and then bass player for Starship, are racing camels. Bottles of dropper acid are passed around. Thai stick and blonde Lebanese hash are toked. It’s close to show time now so I take my seat for the third night running and wait for the shadow of the earth to cover the moon with the aid of musical stimulants.

My neighbours in the bleachers turn out to be Freiberg and Kesey, both sporting pupils like saucers. “Owsley’s finest, no doubt. A secret stash. Prepare for take off!” Kesey roars as Freiberg produces a dropper with, it turns out, Owsley’s liquid windowpane LSD 365. “A special occasion drug, it won’t be repeated,” says Kesey as Freiberg drops it in my eyeball. “A small package of great value just came your way. Sit back and enjoy it like us old timers.” Indeed I do.

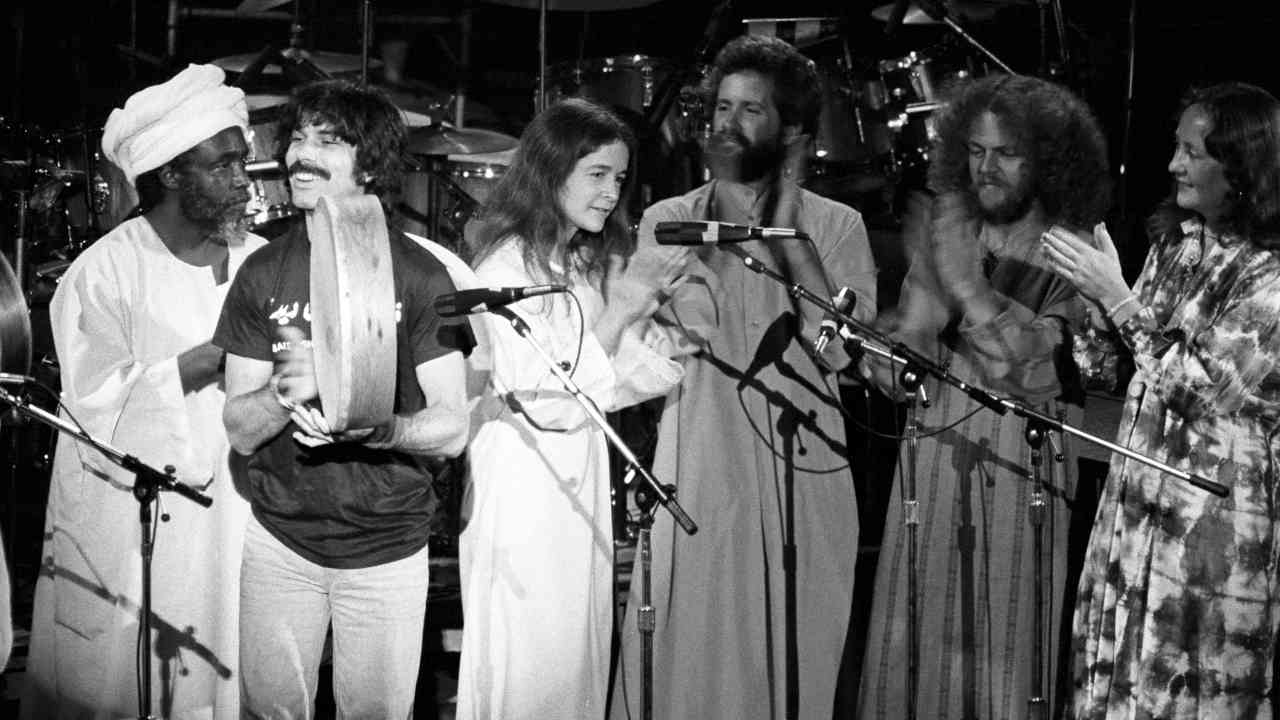

For the next… Allah knows how many hours, the supermen of psych rock lock onto their serpentine groove with Billy Kreutzmann’s heavy toms pummelling Bertha, The Young Rascals’ Good Lovin’ and the ever-spooked Candyman. Local oud legend Hamza el-Din, godfather of Nubian night music, who’s been in California giving Hart drum lessons, drifts in and out of a lengthy Egyptian space jam, manoeuvring his troupe of players around plastic bins full of ice and beer, while search light beams strafe the pyramid and Sphinx – the world’s most cosmic monoliths. As the eclipse bites they kick into Chuck Berry’s Around And Around – they don’t stop rocking til the moon goes down.

Afterwards at the Mena, Kesey’s shouting into Lesh’s ear. “That was the Dead like the Dead, man. Fucking crazy. I can’t believe it!” And Lesh is fizzing over. “Did you hear that Owsley feedback when the eclipse hit? I thought the pyramid was gonna levitate. Completely out there.”

For an encore Bill Graham has organised a shindig with sheep’s eyes in Sahara City, ten miles outside Giza. The Dead and the rest hitch up their camels and ride to the hotch-potch of chalets and tents where small jaal goats nibble the dry grass and tiny cats scuttle among Arabian stallions, chasing sand fleas.

Inside the main tent Kesey and Garcia are rapping away, already planning a visit to Khartoum and the Sudan. As it transpires only Weir and Hart will use Egypt as a springboard, visiting Asia Minor in search of riffs and rhythms.

The end of the night, the beginning of the new dawn. Weir, Krassner, Hart and Kreutzmann have swapped dromedaries for horses. The clinking of cans and the aroma of hash receptacles fills the air. Viewed from the north, the pyramids resemble floating space ships. As Garcia put it: “They dwarf the horizon and they may dwarf us, but this is an event, it isn’t about defining musical history.

“Those weren’t gigs, they were the Acid Tests, where anything was okay. Thousands of people, man, all helplessly stoned, all finding themselves with thousands of other people, none of whom any of them were afraid of. It was just magic, far-out, beautiful magic.”

For one night only, the old motto could be used with some precision. In the land of the night, the ship of the sun is drawn by the Grateful Dead.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 124, September 2008

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.