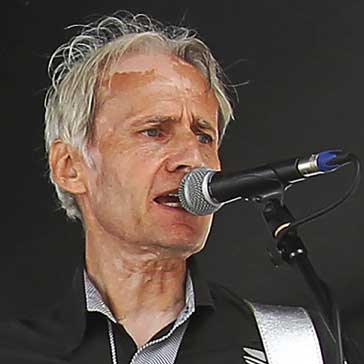

You might not recognise Earl Slick if you saw him in the street. But you would know he is a rock star. With his spiky, jet-black hair and elegantly undernourished physique, the 63-year-old guitarist is rocking a look somewhere between Ronnie Wood and Derek Zoolander. We meet face to face in a rehearsal complex in North London in a room with no exterior windows. But I never see his eyes, which remain encased behind big, black shades.

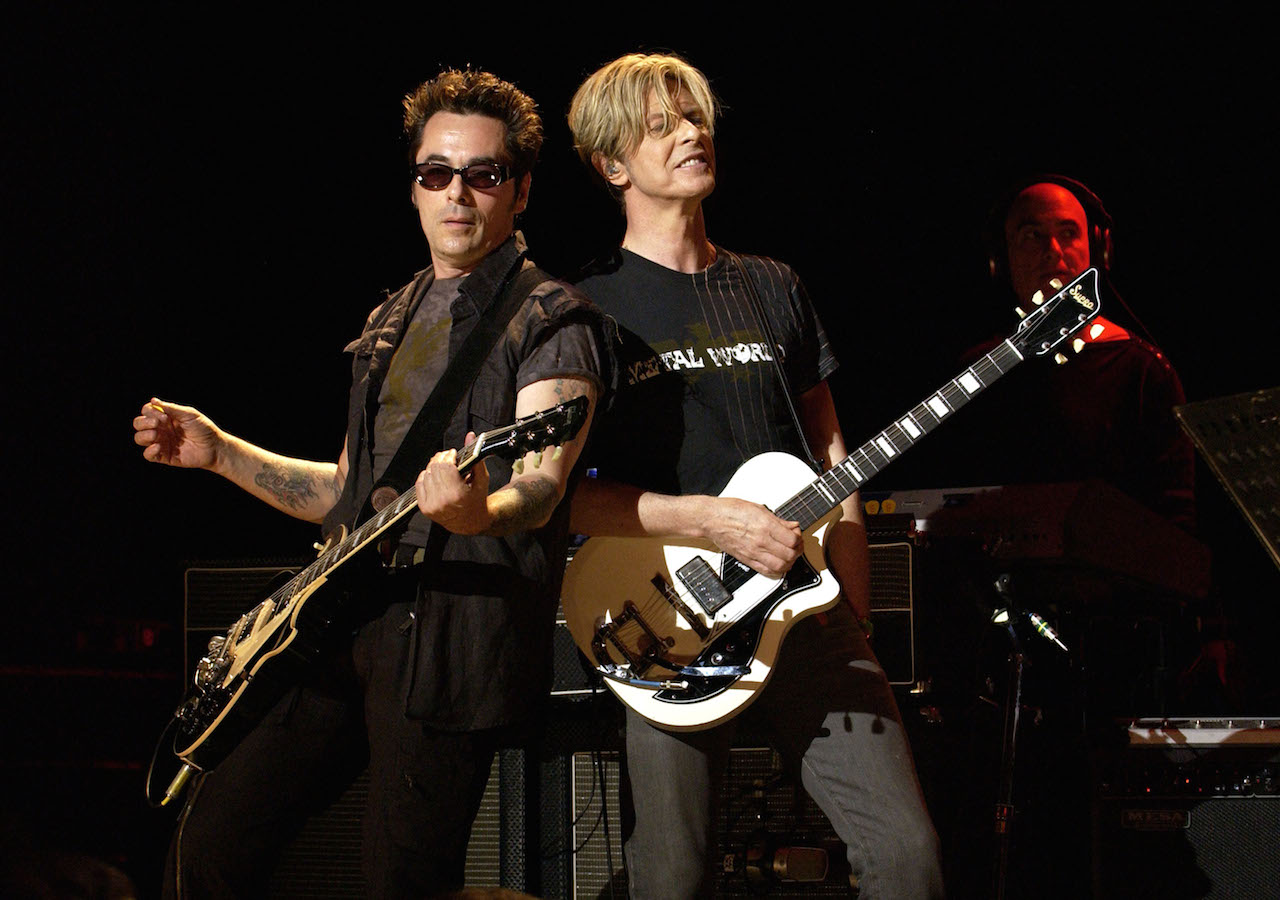

He has been summoned to the capital overnight, under conditions of strict secrecy, to perform in a special tribute to David Bowie at the Brit Awards. As we talk, the sound of various Bowie tracks comes drifting through the studio walls. At one point, Bowie’s voice intoning the familiar message ‘Ground control to Major Tom,’ seems to have got stuck on a tape loop, lending a ghostly backdrop to our chat.

Slick was the most longstanding of Bowie’s many decorated guitarists. The New Yorker, who was born Frank Madeloni in Brooklyn, first joined Bowie for the Diamond Dogs tour of 1974 and last played with him on 2013’s The Next Day. In-between, he played on the albums David Live, Young Americans, Station To Station and Reality and took a key role in the Serious Moonlight Tour in support of the Let’s Dance album. He has also worked with Ian Hunter, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, as well as releasing his own albums both as a solo act and in bands including Dirty White Boy and Phantom, Rocker & Slick.

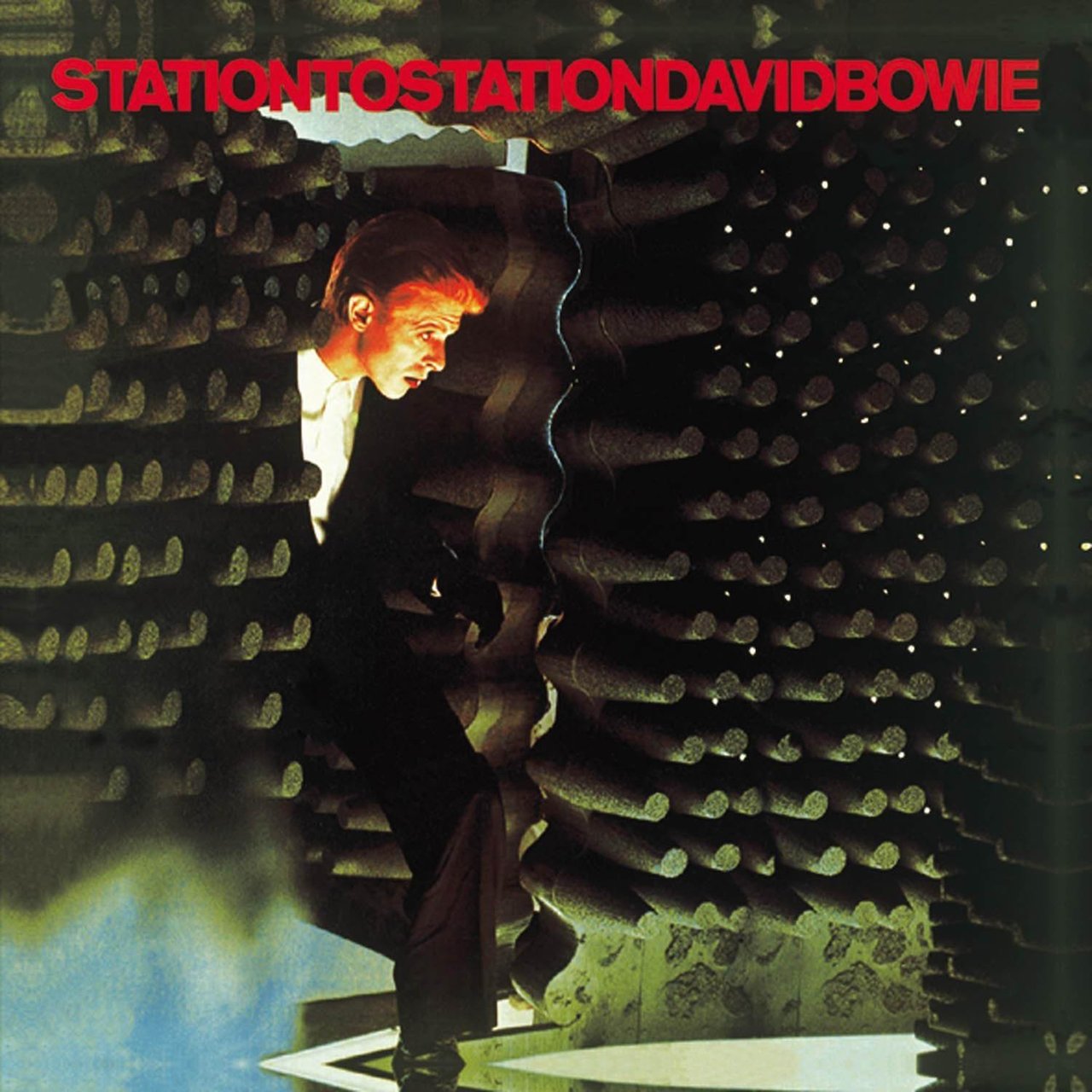

Slick can’t talk beforehand about the Brits tribute (which turns out to be an overture of Bowie’s signature riffs – Rebel Rebel, Ziggy Stardust, Heroes and others – followed by a glorious version of Life On Mars sung by Lorde). But he can and does talk about his time with Bowie, and in particular his part in the making of Bowie’s landmark album Station to Station, released in 1976.

Slick was first recommended to Bowie by the late conductor and composer Michael Kamen, who knew that Bowie was looking for a guitarist to replace Mick Ronson on the forthcoming Diamond Dogs tour, which Kamen also played on. At the audition, the then 22-year-old Slick was understandably nervous. “I wasn’t really sure what DB was going to want, because I never did a job for somebody else before. I thought, ‘Oh my God. Have I got to copy all Mick [Ronson]’s stuff, note-for-note? This is going to be a nightmare.’ Even to this day, I don’t take direction very well. I can’t read music and I don’t like being told what to do note for note, because if I do that it doesn’t sound like me. So why am I there? I’m a stubborn sonofabitch. David picked up all of that. And he said to me: ‘You learn the song and then do it the way you do it.’ I always loved Mick’s playing, but I couldn’t be Mick and I didn’t want to be. Nobody’s going to sound exactly like him, ever.”

The full scale of the challenge – and how incredibly well Slick rose to it – is there for all to hear on David Live, the double-album recorded during the Diamond Dogs tour. It was Bowie’s first live album and became a big hit in both America (No.8) and the UK (No.2). On track after track Slick proved himself a lead guitarist with a surefooted touch and a buccaneering spirit. From the spiralling outro of Moonage Daydream to the breathtaking solo in Candidate and the monumental totality of The Width Of A Circle, Slick dished out sounds and solos that marked him out as a world-class performer. But making the album almost led to an insurrection among the band.

“We were not told that they were recording an album at the live shows,” Slick recalls. “But back then if you were recording something live you would have two sets of microphones: one for the live sound and one for the recording. I was still inexperienced, but the other guys in the band noticed the two sets and figured out what was going on. When they questioned it, we all got a bit of paper under the hotel door offering us a pathetic fee for recording an album. It turned into a dispute between us [the band] and DB’s management. Herbie [Flowers, bass] and some of the others negotiated a decent fee. The management then didn’t pay the money. So we sued and eventually we got paid.”

Bowie’s manager at the time was Tony DeFries, and soon after this and other incidents, Bowie fired him and began legal action to free himself from his contract. “DeFries fucked David over really bad,” Slick says. “He fucked us all over. He was a creep. You can print that.”

While David Live was a tremendous showcase for Slick, he played a subsidiary role to Carlos Alomar on the Young Americans album in 1975. “I’m playing guitar on a lot of the record, but it’s really background stuff,” Slick says. “That’s really a Carlos album. I think he did a great job. When you make records you got to do what works. What does the song need? If it doesn’t need me on it or it just needs me to be in the background, fine. You play for the song.”

The emphasis shifted decisively, however, on Station To Station, an album which found Bowie at the crossroads between his rock/R&B background and the experimental pop/electronica sounds of the future. Slick whose playing style combined old-school lead guitar references with a natural taste for the wilder frontiers of sonic experimentation now found himself at the heart of the creative process. The 10-minute title track, with its opening blizzard of feedback, set down a marker at the beginning of the album.

“That happened at about five in the morning. That was just me and David in front of Marshall stacks in the studio both feeding back at the same time. It was spontaneous. When those kind of things came along, I was ready. We fucked around a lot with the guitars and messed around with ideas. You’re asking me to get together with DB in the middle of the night and make some out-there shit? I’m right on it!”

Station To Station was recorded at Cherokee Studios in LA at a time when Bowie’s personal excesses had escalated to a point where he could remember very little about making the album. “I know it was in LA because I’ve read it was,” Bowie later remarked of the sessions. It is said that his diet at this time consisted of red peppers, cocaine and milk.

“The red peppers, I don’t remember,” Slick says. “But I remember all he ate and drank was milk. And all I ate and drank was beer. We were both out of it, all the time. I remember being in a bar in Hollywood one night and around two in the morning I got a call. There’s a car waiting outside. David wants to go in right now and cut some songs. So I jump in the car and off to work. Another time I remember finishing a session at four am [after] thirty-six straight hours in the studio.”

Bowie was deep into his Thin White Duke character at this time. Did this spill into his personal relationships?

“Hell, yes,” Slick says. “Everything did. Everything any of us did spilled over. Whenever you’re in a situation like that your habits and your thinking spill into the work. And sometimes that’s a really good thing and sometimes it’s not. Christ, we almost killed ourselves with all this shit. We’re lucky we didn’t. But that record never would have been the same if we’d been in a different frame of mind.

“I don’t condone that people need to get fucked up and take a lot of drugs and shit to make cool music. But I think that the whole environment at the time – the 1970s, the drugs – had a major impact on what that record sounded like. It had a major impact on everything. And actually I think that record benefitted from the insanity that ensued while we were doing it.”

Less beneficial was the effect that this snowstorm of cocaine and sleepless nights eventually had on communications between Bowie and Slick. Although Slick had been at the heart of creating and recording Station To Station, somehow, when the tour to promote the album began in Canada in 1976, he had been replaced by the untried Stacey Heydon.

“There were malevolent people behind the scenes that pitted me and David against each other,” Slick says. “We were maybe a bit compromised in our mental states and didn’t realise what was happening. We both thought that we’d been fucked over by each other. The fact of the matter was that the powers-that-be had played some manipulation games, and me and David not really having our eye on the ball didn’t see what was going on. Later [in 1983] when I came into the Serious Moonlight tour, we knew we had to clear the air. Once we sat down and talked, it all made sense. Basically I got fucked out of a gig and he got fucked out of a guitar player, because there was just nasty people who had agendas. This wasn’t Tony DeFries. I don’t even want to give you these guys’ names. They don’t deserve the recognition. If you’re really curious and you want to go into the archives, you’ll see the names.”

Slick will be embarking on a run of UK dates in April to mark the 40th anniversary of Station To Station, during which he will be playing the album in its entirety. The shows were planned last autumn at which stage Slick, like most people, was unaware Bowie was ill. The guitarist was adamant that he did not want a Bowie clone to sing the album and so he decided to join forces with Bernard Fowler, best known as backing vocalist with the Rolling Stones. Also in the line-up for dates in Glasgow, Liverpool and London is Lisa Ronson (daughter of Mick) who will be singing BVs with Slick & Fowler, as well as opening with her own band.

Slick has always been a fierce advocate of Station To Station and now, with these shows looming, has become evangelical about it. “I think it is one of the most important records anybody has ever made,” he says, sitting forward, voice rising. “Tell me anything that was even close to sounding like that, up until that point in the rock era. There’s nothing. I would call it the first really sonically experimental record by a major artist – barring Frank Zappa. The writing, the production, the lyrics. Who the hell put a 10-minute title song as the opening track? Nobody did. I don’t think there was any conscious effort to make a ground-breaking new thing. I think it just happened. And that’s why it’s so good. It wasn’t contrived. I just went in there and David was writing and it just happened. That’s when shit is cool. When it just happens.”

Despite his contributions to the songs, Slick received no share of the writing credits, a subject that he doesn’t care to dwell on. “It’s a very grey area. I’m not sure that writing a lick means that you wrote the song,” he says. “Maybe I should have got a credit for something. I don’t know. That’s really up to the artist to do that. Or up to me to demand it. But then it’s all passed down in the end. I can tell you that the Golden Years lick is a combination I ripped off from Clapton’s Outside Woman Blues and Wilson Pickett’s Funky Broadway. I had both those songs in my head when David wanted a lick for the chord sequence he’d got. So thanks, Eric.”

Slick rejoined Bowie’s touring band after Stevie Ray Vaughan – who played guitar on the Let’s Dance album – jumped ship on the eve of the Serious Moonlight tour.

“I came to save the day again,” Slick says, recalling that he only got the call two days before the tour began. “I’m the go-to guy if the house is on fire!”

Slick never set out to be a firefighter. In a long and illustrious career, he has put out half-a-dozen or so albums under his own name and embarked on a string of collaborations in groups including Silver Condor, Phantom, Rocker and Slick, and late-80s glam rockers Dirty White Boy.

After performing again with Bowie on his Heathen tour and his Reality album and tour, Slick reconnected with DB for the last time for The Next Day. Had Bowie changed?

“He really wasn’t any different. He just wasn’t working as many hours. There were no health issues that I was aware

of. He looked fine. I couldn’t tell you anything that was happening in David’s life outside of music because he was very private – as I am. It’s not that I want to hide anything, it’s just that it’s none of your fucking business.”

Bowie, nevertheless went to remarkable lengths to keep secret the fact that he was even recording an album, requiring Slick – along with everyone else involved – to sign a non-disclosure document.

“Why not?” Slick says. “It’s his record. He wants it quiet, he gets it quiet. It was a one-page document that just said ‘Shut up’.

“As a sideman, your whole thing is to make sure that guy that’s in front of you, you’ve got his back. You’ve got it on stage and you’ve got it in the studio. ’Cause it’s not your name on the marquee. It’s his name and you’ve got to do everything you can to make sure he’s got the band behind him. That’s your fucking gig, man.”

Earl Slick & Bernard Fowler Perform Station To Station in the UK from April 22.

GREATEST ALBUMS OF THE 70s: #5

David Bowie - Station To Station (RCA, 1976)

Although a massive influence on the new wave movement of the late 1970s and beyond, Station To Station arrived midway through a period when Bowie was in creative overdrive, and was rather overlooked at the time as one of a flurry of DB albums that rearranged the furniture in the palace of pop.Beginning with the sound of a steam train panning across the speakers, Station To Station was a trailblazing voyage through a pop world in a state of flux. With only six songs spread over two sides, it was both epic and concise as it straddled the divide between Bowie the established chameleon pop star and Bowie the emergent art-rock experimentalist.It introduced Bowie’s last great persona, the Thin White Duke, who was referenced in the opening lines of the album’s title track, a 10-minute odyssey that was the longest and arguably most ambitious song he ever recorded. Musically ground-breaking and defiantly ‘out there’ it was also one of Bowie’s most melodically adept albums and a major chart success, peaking at No.5 in the UK and No.3 in the US.

What they said at the time: “It offers cryptic, expressionistic glimpses that let us feel the contours and palpitations of the masquer’s soul but never fully reveal his face.” Circus