On January 17, 1992, Green Day released their second studio album, ‘Kerplunk’, through Lookout! Records. Just over two years later, the Berkeley trio became a worldwide phenomenon following the release of their major label debut, ‘Dookie’. So who better to recall the teenage band, the Gilman Street underground and the fledgling punk label by the man who started it all – Larry Livermore…

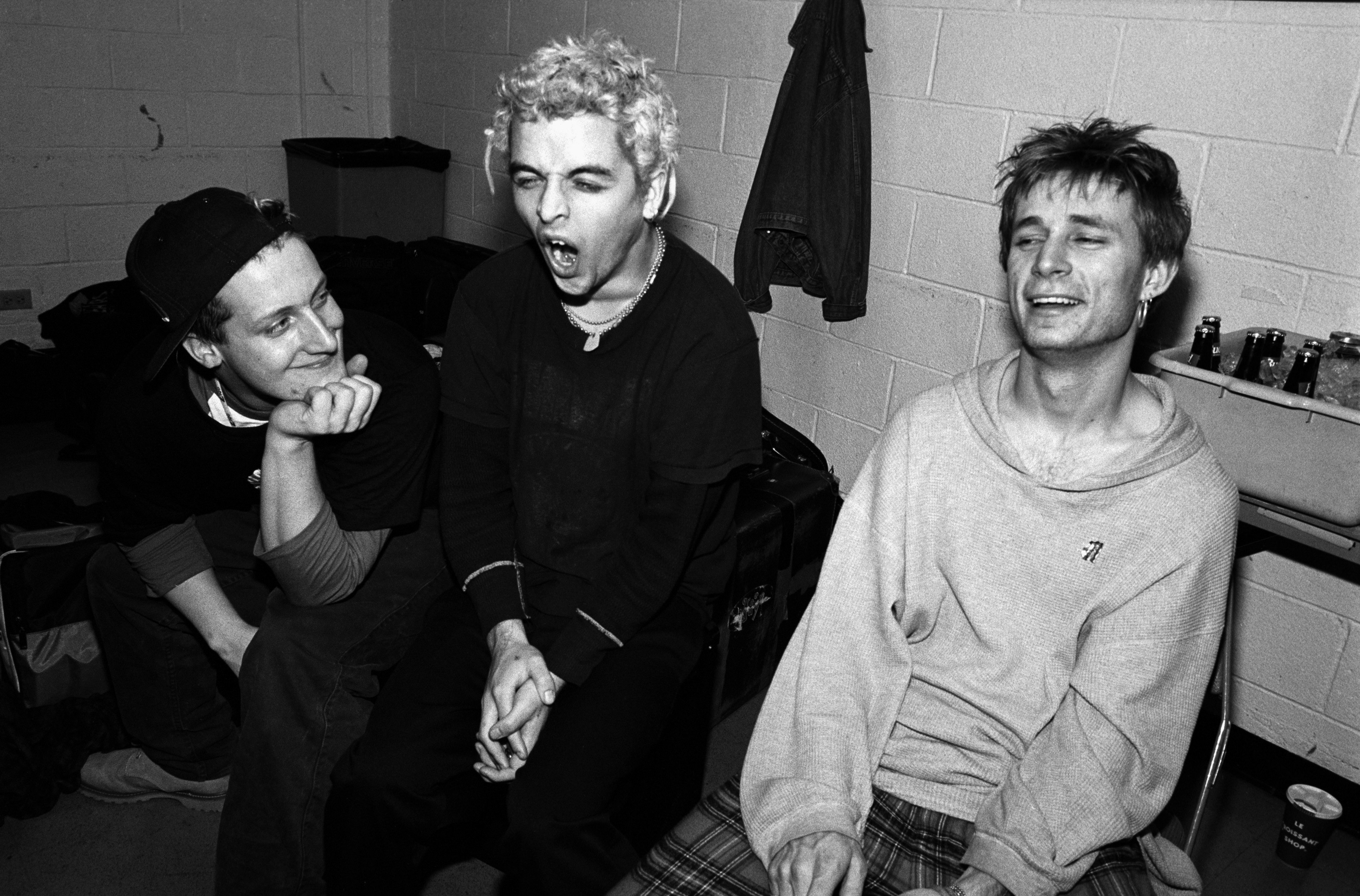

The Lookouts (from l-r): Tré Cool, Kain, Larry Livermore

“What’s the East Bay?” people often ask me. The answer is that it’s a sprawling mass of suburbs – some middle-class, mostly working-class – stretching along the eastern side of San Francisco Bay. The snobs over in San Francisco used to call it “East Berlin” because it was supposedly so drab and grey.

It’s not that bad, really, but in 1986 it wasn’t exactly a hotbed of punk rock activity. In fact, it was more like living in a graveyard. The few shows that happened typically took place in illegal warehouse venues or someone’s basement or garage, and they were always getting shut down by the cops, or ending up in fights or with the joint getting trashed.

After all the excitement of the late-70s/early-80s punk explosion, it was depressing. Most people figured punk was dead and buried, but a few of us weren’t ready to give up just yet. We found an empty warehouse in the wastelands of West Berkeley and talked the city into letting us fix it up as an all-ages, volunteer-run club. We called it the Gilman Street Project, but soon everybody knew it simply as Gilman Street, or just plain Gilman.

It was like that film, Field Of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come.” When Gilman opened there was only a handful of bands in the East Bay; within months bands were coming out of the woodwork. Half of them were still in high school. Kids who never even thought about being in a band saw their friends up on stage and thought, “If they can do that, why can’t I?”

One of the youngest kids at Gilman was in my band, The Lookouts. I gave him his first drum lesson when he was 12, and he joined our band a week later. “You need a punk name if you’re going to be in a punk band,” I told him. “From now on you’re Tré Cool.”

Tré was 13 when we recorded our first album, and 14 when we started playing at Gilman. When he was 15, he set up a show that would help change rock’n’roll history. “Some kids at my school are having a party this Friday night,” he told me. “Can The Lookouts play?”

We were living in the backwoods of Mendocino County, a remote, mountainous area 140 miles north of the East Bay. We were always having to drive down there to play shows, so we were happy for a chance to play close to home.

Then I got a call from John Kiffmeyer, aka Al Sobrante (after his hometown of El Sobrante). John had played drums in a Gilman band called Isocracy, who were famous for their practice of bringing huge bags of rubbish to shows – everything from old bicycle tyres to mannequins to mountains of confetti – and throwing it at the audience. Who of course threw it right back.

“Listen,” he said, “I’m in a new band with these two kids from Rodeo. We’re called Sweet Children, and I was wondering if you knew any shows we could play.”

“Not much going on right now,” I told him. “The only show we’ve got coming up is this high-school party that Tré set up for us.”

“Can we play too?”

“Dude, it’d be a 280-mile round trip for you guys, it’s up in the mountains, it’s supposed to snow, we don’t even know if anybody will show up. And there’s no money for the bands, not even for gas.”

“We’ll be there,” said John.

The ‘party’ was a total fiasco. When we got there, five kids were standing around freezing outside an old wooden cabin. Nobody had a key, so we had to break in. There was no heat except for a wood stove, no light except for candles, and no electricity until we brought in a generator to power the amps.

But none of that mattered when Sweet Children started playing. Billie Joe and Mike were barely 16-years-old at the time, but you’d have thought they’d been on stage all their lives. The ‘audience’ might have been five kids sitting on the floor in a candlelit cabin, but Billie treated them as if they were a packed house at Wembley Stadium.

I was in awe. I’d seen amazing bands in my time – the MC5, The Stooges, the Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, to name a few – but these kids were already in that class, and this was only their third or fourth show ever.

They finished their set and Billie walked over to me and shyly asked, “So what did you think?”

“I want to put out your record,” was all I could say.

I don’t know if he took me seriously. I’m not even sure how serious I was. But a couple of months later, Sweet Children were in the studio recording four songs for their first 7” EP, ‘1,000 Hours.’ Two weeks before it was supposed to come out, they told me they were changing their name to Green Day.

“What, are you crazy?” I said. “You can’t change your name at the last minute! How will anybody know it’s you? Besides, Green Day’s a stupid name. It doesn’t even mean anything.”

I should have saved my breath. They might have been just kids, but when it came to band stuff, they knew what they wanted to do and went ahead and did it. We made a new cover, and the record came out on schedule in April 1989. It didn’t sell much – maybe 1,000 copies that first year – but that was OK. I’d started Lookout! Records a couple of years earlier with $4,000 saved up from my dole money, and never really expected to make any of it back. The biggest record we’d done so far was a 7” EP by another Gilman band called Operation Ivy, which had sold about 2,500 copies (their album, which came out a month after Green Day’s first 7”, would go on to sell around a million). What mattered most to me at the time was that at least a few Green Day songs would be preserved for posterity. With bands regularly forming and breaking up every few months, that was no small thing.

Green Day didn’t break up, though; instead, they played every show they could get, no matter how tiny or inconsequential. Some punks sneered at them for being ‘too pop’, and at least once they were refused a show at Gilman for that reason. They weren’t the only future superstars to have trouble getting a gig there: Nirvana got turned down because “nobody’s ever heard of you guys”.

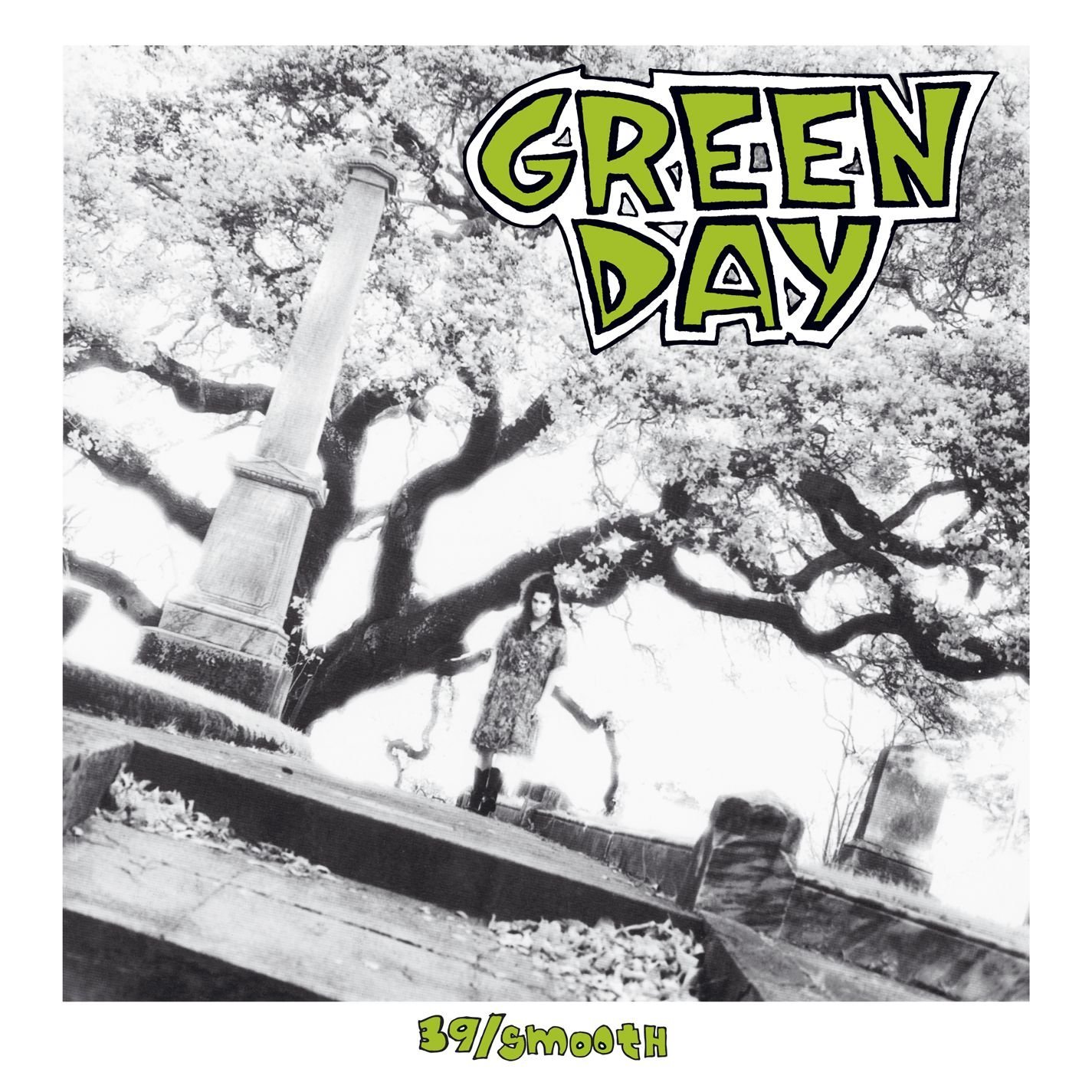

Later that year, I sent Green Day into the studio to make an album. They spent two days and a grand total of $675 to produce ‘39/Smooth’ (later re-released on CD as ‘1,039 Smoothed Out Slappy Hours’). It came out in April 1990, and that summer the band set out on their first national tour.

It wasn’t the most professional of tours. Their first stop was Arcata, a small college town on the North Coast, and when Green Day arrived, they discovered that nobody had bothered to organise anywhere for them to play. The show went ahead anyway, in the living room of someone’s apartment.

Things went much more smoothly after that, if you don’t count the usual problems with broken- down vans, cancelled shows and dodgy promoters, and Green Day were having the time of their lives. While in Minneapolis, the band recorded a four-song EP of some old Sweet Children songs, and Billie Joe met the girl who, four years later, would become his wife.

By the time they got back to Berkeley, everything seemed to be going Green Day’s way. The album was selling well, they were being offered gigs everywhere and Billie and Mike couldn’t wait to get back out on the road again. But John had other plans. It turned out he’d been planning on moving to Arcata for two years to finish college, but hadn’t got around to telling the band about it. Billie found out from some mutual friends.

“It blew me away,” he told me. “I was hurt. One, because I had to hear it from someone else, but also because John was a big influence to us. We were so young, and we learned a lot from him.”

It looked like the band might be over just when it was really getting started. John told Billie and Mike that he’d come back for shows now and then, but apart from that, they’d have to put the band on hold for a couple of years. “We were far too young and full of energy to wait six months or a year for someone to play gigs,” said Billie. “At 18, that’s like half a lifetime. At the same time, I had this romantic thing about how the gang doesn’t split up, the band doesn’t split up. I didn’t want to look or another member – it was too cheesy, too lame.”

As it turned out, they didn’t have to find another member: he was there all along. A couple of months earlier, Billie had come into the studio with The Lookouts to play some lead guitar and add backing vocals for what would turn out to be our last record.

We’d shared many gigs, going back to that mountain party in 1988, but this would be the first time Billie and Tré actually played music together. After John left for college in September of 1990, Billie and Mike started jamming with Tré, and in November Green Day played their first show with Tré on drums.

I was excited to see how well Tré blended in with the band, but sad, too, because I knew it probably meant the end of The Lookouts. Tré didn’t become a fully fledged member right away. John was still coming back to play some gigs, but he was also playing with another band at college.

That winter, Green Day shared a gig with John’s new band, The Ne’er Do Wells, and Billie remembers, “John was playing really hard, trying to make it look like he was the man, and one thing you cannot do to Tré is outdrum him. One of the first songs we played was Longview, which is a great drummer’s song, and from that point on, it was like, ‘Dude, you’re so over.’”

Once they’d settled on Tré as their permanent drummer, I urged Green Day to get back in the studio to record a new album. It turned out they weren’t quite ready; they laid down six tracks before admitting that was all the material they had.

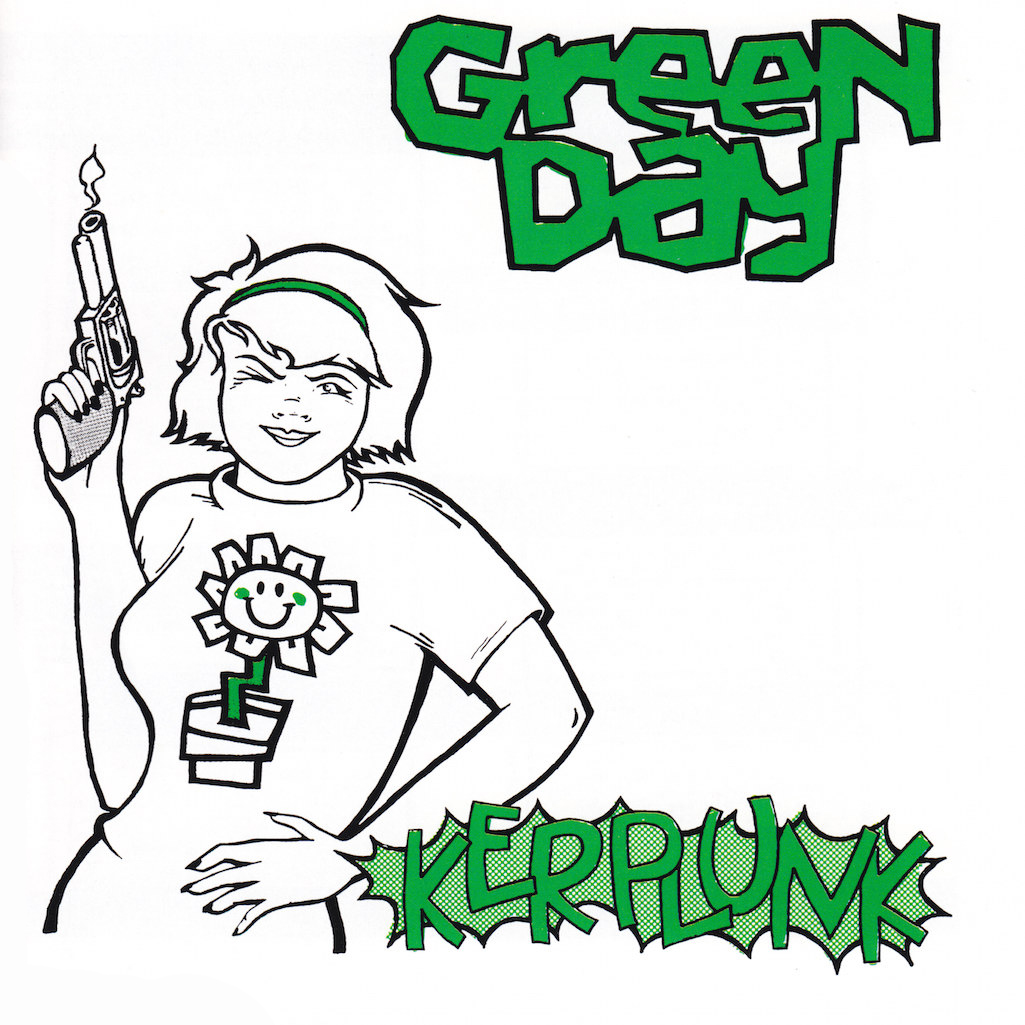

I feared that without John to keep things organised, the band might start drifting, but I needn’t have worried. That autumn they went back to the studio, re-recorded the original tracks along with six new ones, and emerged with their second album, Kerplunk.

By now, Lookout! Records was doing well enough to be able to afford more studio time, so I told the band not to feel like they had to rush things. They did anyway; the album was done in three or four days and cost less than $2,000. Not bad for a record that would go on to sell more than a million copies.

I took the tape down to LA to have it mastered, and afterwards made a cassette copy for myself. I popped it into my Walkman as my plane was taking off for the journey home. The first chords of ‘2,000 Light Years Away’ kicked in, and it was so good it was almost scary. I knew instantly that life was never going to be the same again for Lookout! Records or Green Day.

We sold 10,000 copies of Kerplunk the day it came out, which might sound like nothing today, but for a tiny, underground label being run out of my equally tiny bedsit, it was amazing. By the end of 1992 it was up to 50,000. We were still flying under the industry radar, but not for much longer.

I was used to seeing Billie, Mike and Tré all the time, at gigs or hanging around the Lookout! ‘office’, but now they were touring so much, that was no longer the case. They repeatedly criss-crossed the US, Canada and Europe, first in an old van, then in the converted bookmobile Tré’s dad fixed up and drove for them.

I was on tour with the Mr T Experience in Poland, not long after the communist government had fallen, and as we pulled into Bialystok, the last town before the Russian border, I thought, “This has got to be the first time an American punk rock band has played in this part of the world.” Then I saw the huge ‘Green Day’ spray-painted across the town’s water tower. They’d been there, done that, months before us.

Back in Berkeley I kept hearing rumours that the major labels were chasing Green Day. The next time I saw Tré, I asked him what was going on. He hummed and hawed, but I’d known him too long for him to be able to keep a secret. “We’re talking to a management firm,” he finally said, and when I rounded up Billie and Mike for a meeting in a nearby cafe, I found out they’d already signed a deal. I thought they’d be better off doing at least one more record on an indie label, but their minds were made up, and I wished them well.

They disappeared into the studio for much of the summer. Their first two albums combined had taken less than a week to record; they spent more time than that just setting up the drum sounds for Dookie.

When it was done, they brought me an advance copy, and I was amazed. It was the same Green Day I’d always known and loved, only about 100 times better-produced. As good as the record was, though, I wasn’t sure their new label would know what to do with it. The kind of music Green Day played was still very much a cult sound at the end of 1993. I’d seen other great bands try to make the leap to the mainstream and get unceremoniously dumped if they didn’t produce big sales right from the start.

But judging from the local shows Green Day played while waiting for Dookie to be released, that wasn’t going to be a problem. They weren’t just sold out; they were crawling with media and MTV types. Somehow the word was getting out, even before the record did.

Gilman Street has a rule that no band signed to a major label can play there, and even if that rule wasn’t strictly enforced, the kind of crowds Green Day were now drawing could never fit into the 300-capacity warehouse. But at Christmas time, 1993, they played one last show there under a fake name.

The club was only about half full, and almost everyone knew each other. We sang along with the band and danced and smiled bittersweet smiles, kind of like it was the senior prom and we’d all soon be going our separate ways. Someone said to me, “I know Green Day are going to be huge, and I’m happy for them, but I’m sad, too, because our little scene is never going to be the same again.”

Green Day, 1994 Photo: Catherine McGann/Archive

A few weeks later, Dookie was out and Green Day were off on a constant round of touring to promote it. It was all or nothing at that point; they didn’t even have a home to come back to. As Billie put it, “I was sleeping on someone else’s mattress. It was someone else’s room. I put my clothes in a garbage bag, grabbed my guitar and my four-track, and I left.”

I didn’t see the guys again for a few months. I caught up with them in London, where they played a sold-out show at the Astoria. I hung out with them backstage for a while, but the celebrities and TV lights were getting on my nerves, so I started walking home along the Bayswater Road. A bus pulled up alongside me and someone yelled my name. Tré was hanging out the window, shouting, “What are you doing out there, doofus? Let’s go party!” I jumped in the bus and he showed me the video they’d just finished for their next single, Basket Case.

Late that night, we ended up in a bar in Maida Vale. Green Day’s manager had just flown over from the States, and he was waving a copy of the new Billboard magazine. Reprise had taken out a full- page ad that said simply “’Dookie’ Is Gold”, in honour of the album having sold its first 500,000 copies.

It seemed like a long way from that freezing cabin on a remote Northern California mountainside, playing for five high-school kids by candlelight. But it wasn’t really. The band that loved music so much that they’d play anywhere, any time, for anybody who would listen, hadn’t really changed at all. They’d been superstars all along. The only difference was that now the whole world knew it.

This feature first appeared in Metal Hammer Presents: Green Day.