March 24, 2016: Greg Lake is on the phone talking to me about the death of Keith Emerson, who took his own life just 13 days earlier.

“One of the things I think Keith got to resent about me was that I would tell him if I thought something he’d written wasn’t very good… it’s not an easy thing to tell someone that. If we argued about music it’s because we were both passionate. That’s when people clash, but that’s where you’ll find great music.”

It’s said that how you hold yourself in the face of a challenge or overwhelming adversity is when you find out who you truly are as a person. Although Greg Lake had been diagnosed with cancer for some time, there had never been any announcement about him having the illness. So when the news of his death from the disease was made by his long-term friend and manager, Stewart Young, via Lake’s website on December 8, 2016, it came as a bolt of the blue to his fans.

While some cancer sufferers have found it therapeutic and even comforting to share their struggle in public, that approach wasn’t one that interested Lake. For a man who’d spent the bulk of his entire adult life in the glare of publicity, when it came to his personal life, and that of his family, he was intensely private. While understanding the professional applications of social media, Lake was bemused at the modern-day obsession with selfies, pet portraits and political rants. As one close friend observed, he couldn’t see the point of letting fans know what he was having for breakfast, or what television show he was watching.

Speaking to the Daily Express’ Martin Townsend in an interview given in 2015 but only published after he’d died, Lake explained, “If I announce that I’m ill it’ll be all over the internet and, I know it sounds awful, but I don’t want all the sympathy that will bring. I don’t want to have a Facebook death.”

Understandably daunted by his diagnosis, he faced the illness without fuss or drama, enduring rounds of nausea-inducing chemotherapy with stoicism, and bore the ravages and resulting incapacitations of the treatment with dignity. After years of fighting, which had left him unable to play the guitar, he told Townsend he decided to abandon treatment. “I’m not frightened of dying but I don’t like the idea of leaving so many people that I love behind, and I want to enjoy this time with them. I don’t want to be feeling sick and tired from the drugs.”

What made Lake’s death all the more shocking was that it came so close to Keith Emerson’s tragic passing in March 2016. The proximity of these unrelated deaths seemed especially brutal. I spoke to Lake in the immediate aftermath of Emerson’s death from a single gunshot wound. Discussing the death of an old colleague and sparring partner in any circumstances is never easy. Such occasions bring with them all sorts of feelings, memories and associations, good and bad. Lake, though as shocked by the news as everyone else had been, responded in the frank and candid manner for which he was known.

He readily acknowledged some of the difficulties the pair had encountered along the path of what had been a remarkable, and remarkably successful, career together. There’d been differences but there had also been the camaraderie that comes from being on the inside of that world. And every sentence and judgment Lake offered regarding Emerson and the legacy that would survive him came weighted with the acceptance that Lake himself was facing his own mortality.

While knowing the rumours of his ill health for some time, I understood that this subject was necessarily off limits. On that afternoon in March, as he reacted to the news of his old colleague, whose light had so suddenly been snuffed out, there was no hint that I was talking to a man who knew himself to be approaching a finite point, beyond which he too would never again be able to speak to, or touch, or kiss those he dearly loved. To be able to hold yourself upright and carry on, despite the presence of that dread burden, requires special reserves of strength and courage.

Tied in with his lack of enthusiasm for social media, Greg Lake subscribed to the now old fashioned view that a bit of mystery about the life of an artist was a good thing. I made the point to him that fans often have a very deep sense of personal connection to a player through the music. He agreed.

“In the sense that there’s no veil over the music. You play it from the heart, or you should do, and there should be a direct passage into your soul. People sometimes like to give off an image of themselves which is not necessarily who they are. So maybe you could tell more about a person, I think, from the music than you can from the press or things you might read, or even what the person themselves might say.”

What Greg Lake was saying was that if you want to know who the person truly is, it’s probably best to look for them in the music they made.

It’s November 1968 and Michael Giles, Peter Giles and Robert Fripp are sat at the table in the flat they share in Brondesbury Road near Kilburn Park. As a trio, Giles, Giles And Fripp had been at it for a year, during which time they’d released an album, blagged their way onto the radio and even a TV show. But they were getting nowhere. The recruitment of a young multi-instrumentalist and songwriter, Ian McDonald, and his hippie lyricist pal, Peter Sinfield, gave them a shot in the arm and some promising demo recordings, but as the month drew to a close, the mood was bleak.

With Fripp, McDonald and Michael Giles leaning in a heavier direction, and Peter Giles, who’d been playing bass with his brother since they were teenagers in Dorset, wanting to continue with GG&F’s quirky pop, a parting of the ways was inevitable. With Peter gone, a replacement bassist was needed. Robert Fripp knew exactly who to call.

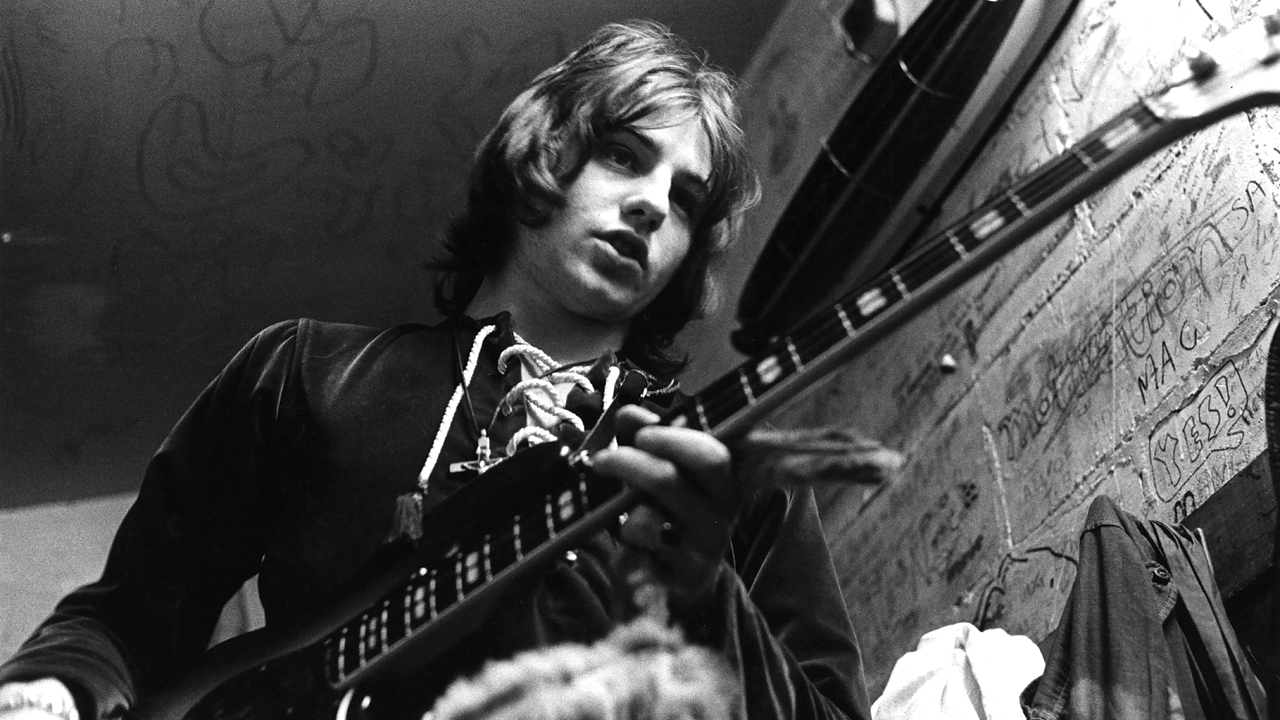

At the time that call was made, Greg Lake had already been a professional musician in the South West for a few years. Like Fripp, he’d cut his teeth on the Bournemouth beat combo circuit, forming his first group, Unit 4, in 1965. Lake remembered seeing Fripp in those early days.

“Fripp used to come along and check me out. He used to jump over the wall at clubs because he couldn’t afford to get in and he would come along and watch me, and at the end of the gigs he would come up and talk and we’d start to chat about guitar and play a bit and so on. We discovered that we’d both had the same guitar teacher and we both had similar guitar techniques and we struck up a friendship. I used to go round to Robert’s house and we used to play guitar duets in his bedroom and that kind of thing.”

Looking back on Lake’s reputation as a local six-string gunslinger, Fripp recalls, “It was obvious to those in the playing pool that some of us would go to the professional route and leave Bournemouth, where semi-professional and professional life were virtually the same. It also seemed likely that some of our team would become successful, and some famous. In my circle, Greg Lake was considered one of the front-runners for fame.”

Lake’s path to success seemed inevitable. He formed The Shame and in September 1967 released their first single. A cover version of Janis Ian’s song Too Old To Go ’Way Little Girl, Lake turns in surprisingly assertive vocals and piercing lead guitar. Even on this early outing, Lake’s voice is completely recognisable, and the addition of Traffic-like sitar locates the disc firmly within the home-grown UK psychedelic movement.

Fripp roadied for The Shame for a week in Penzance while waiting for his place in university, recalling: “Greg and I spent many late nights and early mornings with guitars, trying to make teenage sense of our lives, discussing and planning the future of the world. At the time, Greg was one of my closest friends, and we enjoyed the kind and degree of intimacy which young men with guitars will easily understand.”

Lake moved on to The Gods, an established South West band that featured keyboardist Ken Hensley and drummer Lee Kerslake, both future Uriah Heep members, but he quit prior to their recording debut. In November 1968, the call from Fripp came at exactly the right moment. Showing his pragmatic nature and recognising the opportunity being presented to him, Lake didn’t even bat an eyelid when told he’d be swapping his beloved six-string guitar for a bass.

In December 1968, Lake upped sticks, moved into the Brondesbury Road flat and started rehearsing. Michael Giles recalls being impressed by Lake’s physical presence and the immediate difference his voice made to the sounds they were slowly putting together. “I couldn’t sing like that, Robert couldn’t sing at all, Peter couldn’t sing like that. None of us had that sound or power.”

Ever seen Jimmy Stewart in The Glenn Miller Story, playing the bandleader looking for ‘that sound’? In that vein, a musician or group looking for the moment of epiphany, The Greg Lake Story would almost certainly contain a scene like this:

FADE IN:

INT: cramped, dingy King Crimson basement rehearsal room on the Fulham Palace Road.

CAPTION: JANUARY 1969, LONDON

IAN

(Finishes an abrupt, jazz-sounding run)

So it’s almost kind of swing-type thing I used to call Three Score And Four. Anyone got anything else we could add?

BOB

(Picking up his guitar)

Well… how about we try this?

BOB plays fast-running lines, to everyone’s amazement, and looks satisfied.

MICHAEL

(Plays rattling staccato on the snare drum)

Yeah, that’s great. If we all played that in unison and put stops in, that would sound amazing and blow people’s minds.

IAN

That’s all cool but we need something heavy to kick it in.

GREG

(Looking around the room to each player in turn, smiling broadly)

Well, it just so happens that I’ve this riff and it goes like this…

JUMP CUT TO:

EXT: King Crimson on stage at Hyde Park, playing the opening bars of 21st Century Schizoid Man in front of 650,000 people.

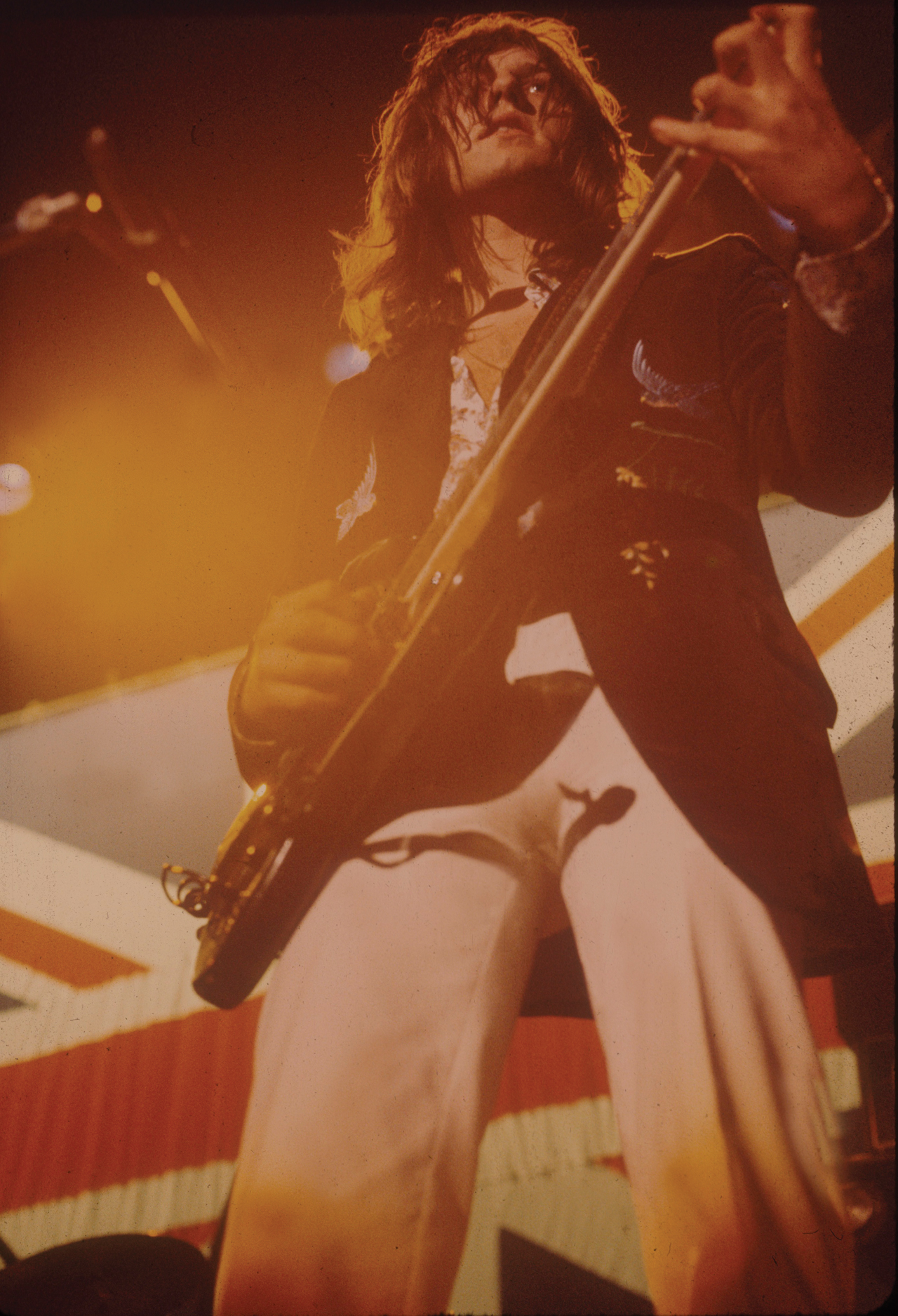

Fictitious cinematic cliché aside, go and watch the scrap of real footage that exists of King Crimson supporting the Rolling Stones in July 1969 and consider this: the guy at the microphone singing, ‘Cat’s foot, iron claw, neurosurgeons scream for more…’ is still four months away from his 21st birthday. Lake had the juice. He had attitude. He had confidence, and bags of it to spare. He flashed a grin and was tuned in, man. He had the look and knew where the good threads were, hauling Fripp down the Portobello Road to kit him out in hippie gear instead of the guitarist looking like a member of the local sixth form college gone AWOL.

Lake smoothed out and slowed down his bumptious Dorset vowels and took on all comers with a laid-back London vibe. He had what playwright Ann Jellicoe memorably dubbed The Knack. He had the looks and winning smile that would win him the ladies. He had the kind of rampant, impatient libido that delayed the start of a King Crimson gig on at least one occasion while he and a lady got it together backstage.

Greg Lake didn’t just bring with him the attention-grabbing riff that opens In The Court Of The Crimson King and inspired generations of guitarists around the world. He brought with him the voice that was equal to the might of the music that surrounded it. Lake was the guy who had the balls to front it all. King Crimson may have been largely unknown at the point at which they played Hyde Park but the fact is, Lake was a rock star already. He was just waiting for the rest of the world to catch up.

He didn’t have long to wait.

Keith Emerson wasn’t so struck with King Crimson when they supported The Nice in the UK and America. He was, however, extremely impressed with Lake’s abilities as a singer and an instrumentalist. Given Emerson’s status as a senior figure on the rock circuit of the day, it might be assumed that Lake came on board as the junior partner. If that was the case then nobody told Lake. While accepting Emerson’s pre-eminence as composer, Lake saw the producer’s chair was empty and he immediately filled it. While that could have been viewed as an example of arrogance, it was, as Lake recalled, a matter of expedience.

“I was the only person who really knew anything about recording, so it fell to me to do it. Also, Keith was very keen on playing and then leaving [laughs] – he wanted to get it done and go, you know? He didn’t want the tedious technical stuff, sitting there for hours, getting a mix right. He wasn’t into that aspect of the band at all. So it came down to me.”

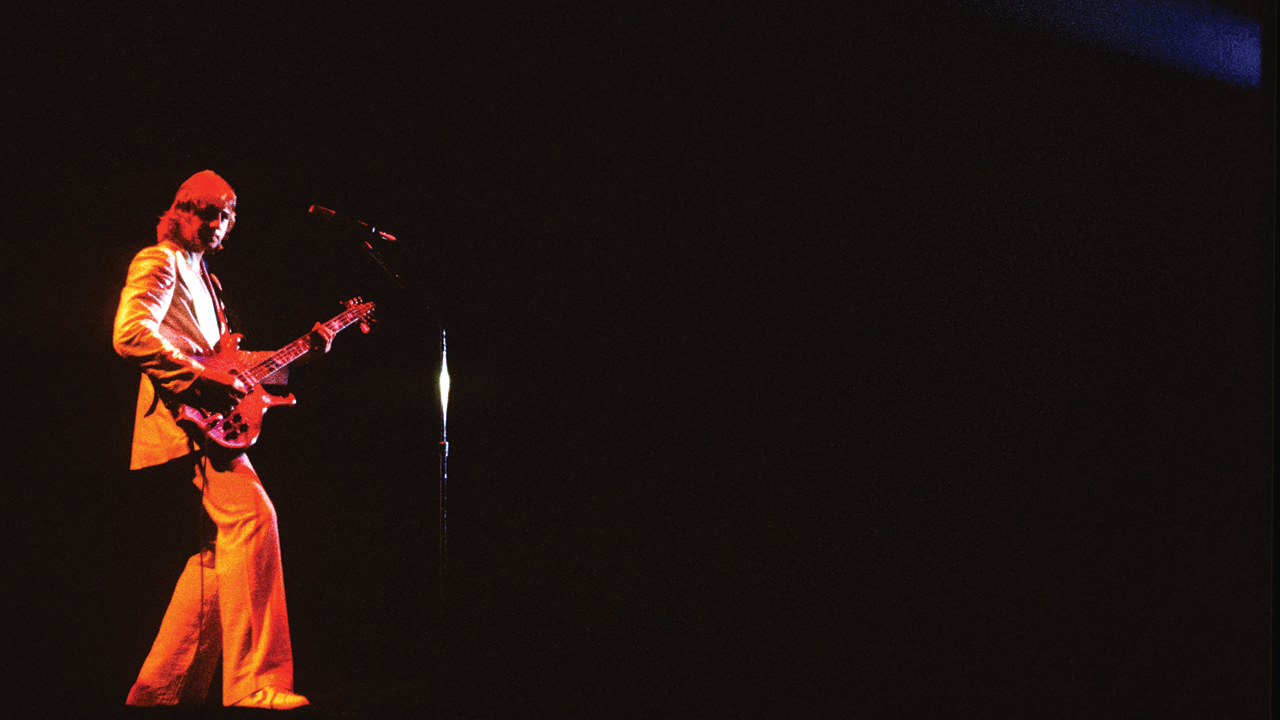

When Brain Salad Surgery was sitting high in the charts in just about every country on the planet that sold records, ELP weren’t just a rock band. They were an imperial force with a fleet of liveried trucks, bound for venues with audiences bigger than some of the towns they sweep past, spreading their high-octane musical Pax Romana to the indigenous populations of the countries they toured one stadium at a time.

When he wasn’t on the road, Lake could be found holding court in his London townhouse, enjoying the spoils and the trappings of success. Smoking Sullivan Powell Turkish cigarettes, he would sometimes refer to the music they played as ‘art’. For sniffy critics, such ostentation was proof of his soulless vulgarity. For Lake, who’d come from the relatively humble background of an asbestos-lined post-war prefab in Poole, there was nothing pretentious about it.

Unlike some rock stars from middle- or upper-class backgrounds feeling awkward about their station in life, Lake, having had no money in the past, had no such inhibitions when it came to grabbing his stash with both hands. Setting himself up in the lap of luxury might well be viewed as conspicuously flamboyant but as Lake saw it, things were simple: he’d earned it through hard work – bloody hard work. If you didn’t like it, well, too bad.

If developing a rough hide against the barbs of the press was an essential means of survival, then so too was becoming inured to mass adulation on the road. “You have to because if you didn’t you’d go mad actually… One minute you’re standing in front of 80,000 screaming people for two hours and then, all of a sudden, the hotel shuts and you’re back in your box again. It’s a pretty stark reality. You do that enough times and its a weird sort of life.”

Away from the instrumental heat and light, Lake renewed his fidelity to the art of the song. Speaking in 1977, he said, “Having to re-evaluate my future really made me think that my strength was in the fact that I was a singer first. And that thought, simple though it may be, took me ages to work out. Because all my life I’ve played in a group. It was a new thing to think of being only me as opposed to being part of a band. You aim to put the best foot forward, to do the thing you can do best. And the best thing I could do was sing songs, so sing I did.”

Our life is defined by the choices we make and how we choose to live it. Greg Lake often said he was lucky – lucky to have done all the things he’d accomplished as an artist and in life. When illness robbed him of his ability to make music, he increasingly took to cataloguing some of those life choices by writing his autobiography.

In March 2016, he told me that he also took pleasure in revisiting the music he made in his heyday – nothing beat the thrill of hearing some of the early ELP records on vinyl again. “Things have a habit of going in and out of fashion,” he observed. “You know what? There’s a metaphor in there somewhere,” he said, laughing with gusto.

We are, each of us, flawed, imperfect human beings, less saintly than we’d perhaps like to believe. In that sense, Greg Lake was just like anyone else. In the course of his career, he’d undoubtedly upset some people along the way, the price perhaps of being someone who set himself high standards in his creative endeavours and expected others to match them. Yet there’s also ample testimony to his acts of kindness, his words of encouragement and compassion.

When it came to recalling a favourite moment of Keith Emerson in action and at the height of his powers, Lake, without any hesitation, offered a memory of Emerson diving into a ripping blues on a Hammond organ. Now, when thinking of Greg Lake, what springs to mind, above all the pomp and circumstance that was part and parcel of ELP, is that deep, sonorous, baritone voice, capable of touching tenderness or rousing within us stirring emotions. As he sang out, as the rich timbre touched the air around us, he could effortlessly bring down the angels or strip the paint off the choir stalls as the material required.

Losing our musical heroes is always hard but losing Greg Lake so soon after Keith Emerson seems especially cruel. There’s that bittersweet moment as our sense of loss is tempered by a poignant celebration as we take comfort in the music he made throughout his life.

For more information, see www.greglake.com.