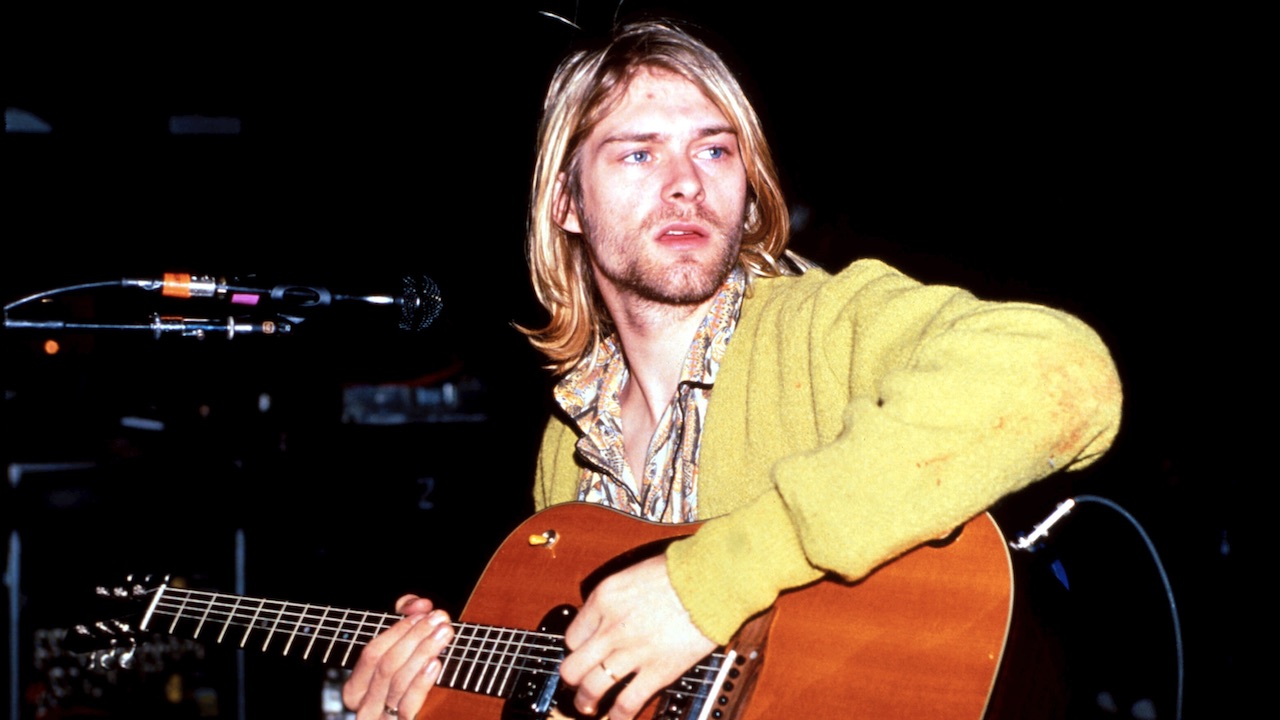

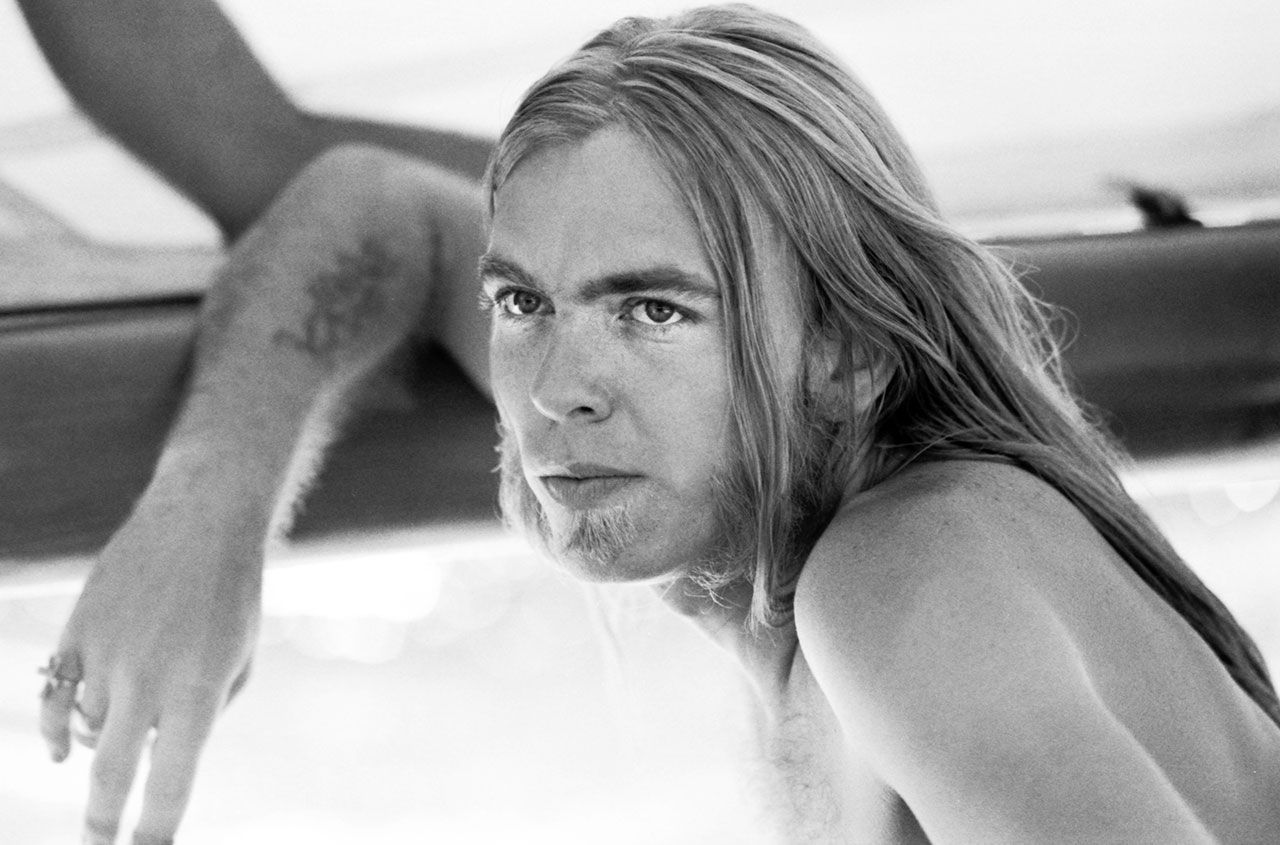

Gregg Allman: December 8, 1947 – May 27, 2017

Classic Rock looks back on the life and legacy of a southern rock legend

Gregg Allman’s life was shaped by death. On Boxing Day 1949, his father, Willis Allman, was murdered near Norfolk, Virginia, where he was stationed with the US Army. The details are unclear; perhaps he was shot by a hitchhiker, perhaps by a drinking buddy (it was the former, Gregg, who had just turned two at the time, said later). And although most accounts say Willis was a captain in the US Aarmy, his own gravestone is inscribed with the rank of second lieutenant.

Twenty-two years later, on October 29, 1971, Gregg’s older brother, Duane Allman, was riding his Harley-Davidson too fast along Hillcrest Avenue in the brothers’ adopted home town of Macon, Georgia, when a flatbed truck stopped suddenly ahead of him. Duane hit the truck and skidded 90 feet with the bike on top of him. Just hours later he died in hospital.

Then, little more than a year after that, Berry Oakley, the bassist in the Allman Brothers Band, crashed his own motorbike into an oncoming bus, just three blocks away from where Duane had been hit. He could have survived had he gone straight to hospital, but he didn’t. He died that same day.

These events shaped Gregg Allman’s life in a profound way. They damaged him, in both his own estimation and the accounts of those around him. But perhaps they also gave him the will to survive; the determination that caused him to fight back again and again; to conquer his own addictions; to re-establish the Allman Brothers Band as one of the biggest groups in America, both after Duane’s death and again in the 1990s, in a third coming that few could have predicted.

They also meant the persona he projected – ornery bordering on mean – didn’t seem to be put on. In the 1991 film Rush, in which he played a drug lord in a performance almost without dialogue, Allman was convincingly terrifying, without actually appearing to be acting.

After Willis Allman died, his widow Geraldine was left with two infant sons, and the struggle to support them. She moved back to Nashville, where Gregg had been born, and the boys were enrolled at a nearby military academy. She would only have done that, Gregg decided, because she hated him. He later realised how wrong he had been. “She was actually sacrificing everything she possibly could – she was working around the clock, getting by just by a hair, so as to not send us to an orphanage, which would have been a living hell,” he wrote in his autobiography, My Cross To Bear.

She also supported young Gregg’s desire to pursue music. After the family moved to Daytona Beach in Florida, Gregg saw a guitar he craved in a shop. He was 95 cents short of the money he needed, and the assistant refused to help him out. He went home and bawled to his mother. “She said: ‘Boy get in the car.’ I swear we eighty-fived it from the house down to Sears And Roebuck. She was steaming by the time she got there,” he told the Savannah Morning News in 2011.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Gregg got his guitar, although it turned out to be Duane who became its de facto owner.

The brothers had a musical prehistory before the Allman Brothers Band came together. By the late 60s, their time in southern clubs had given them the fire and skill to head for Los Angeles. There, under the name the Hour Glass, they recorded a pair of albums that they disdained for their pop fripperies (“Together those two records form what is commonly known as a shit sandwich,” Gregg told Cameron Crowe in 1973), though the song Bells – Edgar Allan Poe set to gloomy psych – was agreeably bonkers. Not all their peers agreed with their own brutal self-assessment, though. Speaking to Billboard, after Gregg’s death, Rickey Medlocke, of Lynyrd Skynyrd and Blackfoot, remembered hearing the band when they weren’t pandering to fashion.“I remember the Hour Glass did a rendition of Georgia On My Mind, and to this day, other than Ray Charles I’ve never heard a rendition like that,” he said. “And I had always wished the Allman Brothers cut that version they did that night, with Duane playing slide and Gregg on the Hammond and the rest of the guys in the band. It was just phenomenal. And I always told him that.”

Soon, though, there was to be a quantum musical leap thanks to Duane’s clean and clear guitar playing, all the flavours of southern music on one plate. That leap owed so much to accident, in the form of a cold remedy Gregg gave to his brother.

“Right before he left Hollywood, on his birthday – November twentieth, 1968 – I took him a bottle of pills for a cold he had, plus a copy of the first Taj Mahal album with Jesse Ed Davis playin’ slide,” Gregg told the writer Barney Hoskyns in 2002. “Well, about three hours later he called me and said: ‘Baby brother, git over here.’ And he’d dumped all the pills out of the bottle, washed the label off and was playin’ bottleneck. The next time I saw him, he was just burnin’. It really put a new charge in him. He entered a new musical universe.”

When Gregg followed his brother back to the south, he discovered Duane had not just reinvented his playing and then honed it as a session guitarist at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, but he’d also decided on the blueprint for what his new group should be: two drummers, two lead guitarists, with Gregg singing and playing the Hammond organ. It turned out to have been something that had been foreshadowed in Gregg’s childhood dreams.

“Between the time I was eight and eleven, I had the exact dream at least ten times,” he told Creem’s Jaan Uhelszki in 1975. “I would be sitting behind a huge block of wood which I could barely see over the top of. As I think back, it was like an upright piano more than anything else. The block separated me from an enormous crowd of people who all looked real strange at the time. They scared me because they were all watching everything I did.Back then, I could never figure out what the dream meant, so I never told anybody about it.

“And then about a year ago it hit me, and I realised that it had been a premonition of what I’m doing today. The block of wood was my organ, and all the people looked so weird because they were out of the times. They looked like people do today – and that was 1957!”

Signed to Phil Walden’s Capricorn Records, part of Atlantic, the Allman Brothers Band recorded a pair of studio albums – a self-titled debut in 1969 and Idlewild South the following year – which failed to set the world on fire. But at the same time they were learning, defining themselves as a band, even if they weren’t yet making a living. In 1974, with the group at their commercial peak, Gregg told Melody Maker about the hard yards they put in as they tried to establish themselves: “In 1970 we worked 256 dates and neither one of us made 1,600 dollars.”

They would travel in a little Ford Econoline van, sustained, Butch Trucks later recalled, by “a great big old bag of Mexican reds [barbiturates] and two gallons of Robitussin HC [cough syrup]. Five reds and a slug of HC and you can sleep through anything.”

The Allmans realised that to be appreciated, they needed to be heard live, where they excelled. And so when the Allmans booked into the Fillmore East in New York for a three-night stand in March 1971 – which they weren’t even headlining, until their performances won them the top slot on the third night – they brought along recording equipment. The recordings from March 12 and 13 were compiled into a 78-minute double album, seven tracks over four sides, which was released as At Fillmore East. It became their breakthrough album, going platinum.

At Fillmore East is a showcase for the guitar playing of Dickey Betts and Duane, but there’s more to it than that. Butch Trucks and Jaimoe Johanson power the songs along – listening to the 23 minutes of Whipping Post, you’re exhausted on their behalf – and Berry Oakley’s bass lines are endlessly inventive. But the still heart of the album is Gregg. It’s not so much his singing – though his voice, soulful and grizzled and expressive, is brilliant – but his Hammond playing. Like Malcolm Young’s rhythm guitar playing in AC/DC, the steady platform Angus needed to bedazzle with his own soloing, Gregg treated his Hammond as a background instrument. It appears to be almost irrelevant at times, yet it adds the colour without which the guitar playing might risk becoming just so many pyrotechnics.

His playing was unfussy, economical and exactly what the Allman Brothers Band needed. And all through his career, he maintained the same attitude: he kept his sound clean, playing at volumes low enough to ensure it didn’t become overdriven. He sought “clarity and emotion of tone”, his keyboard tech Daved Kohls said in 2011, explaining that unlike many Hammond players, Gregg kept his Leslie speaker on a slow rotating speed to keep the sound clean, turning it to fast only for occasional effect.

At Fillmore East made the Allmans the superstars of a new southern rock sound, alongside the likes of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Marshall Tucker Band, but in truth they didn’t have much in common with the choogling boogieing of so many of their peers. The Allmans were steeped in blues and soul; they took their improvisatory flights of fancy from jazz. Compared to most of the groups lumped in as southern rock, they sound much less rock, although maybe even more southern.

It seems extraordinary, now, that music so dependent on individual performances and collective chemistry on any given night – which meant they could fall flat on bad nights – rather than on metronomic, easily replicated efficiency, could have become such a huge live draw, but it did. The Allman Brothers Band began to fill arenas, then stadiums.

Then Duane died, followed by Berry Oakley. And through his grief, Gregg – and Dickey Betts, who became an increasingly important songwriter – propelled the band to ever greater heights. The first post-Duane album, Eat A Peach, was a monster hit, and in 1974 the group headlined to 600,000 people at Watkins Glen.

Nevertheless, things were starting to unravel. The reds and cough syrup of the first tours had been swapped for cocaine and heroin. The studio recordings started to diminish in quality. Gregg became better known for courting and marrying Cher (one of his six wives) than for making music. And then his reputation in Macon was harmed massively by the Capricorn scandal of 1976, when he testified in front of a grand jury investigating cocaine trafficking.

Following the grand jury hearings in January, Gregg’s personal road manager, Scooter Herring, was charged with multiple counts of conspiracy to distribute narcotics. He came to trial in June, and Gregg gave evidence against him, in return for immunity from prosecution. That same year, the Allman Brothers Band broke up.

“He ain’t from Macon any more. He’s got a Hollywood agent, a Hollywood publicist and a Hollywood wife. What do I think of Gregg Allman? Fuck him,” one local told writer Michael Gross the following year.

By this point, Gregg wasn’t exactly helping himself with his music. His 1977 album with Cher, Two The Hard Way, came to be regarded as the worst thing either of them ever recorded. The following years were washouts, during which Gregg occasionally managed to reach the safety of dry land. A first Allman Brothers Band reunion came and went; the drugs and the drink continued to govern his life, despite repeated visits to rehab; his solo career drifted.

The first turning point came in 1990, when the Allman Brothers Band recorded a new studio album, Seven Turns, which proved to be tough and focused. The next year they recorded an equally strong successor, Shades Of Two Worlds. Gregg wasn’t contributing a lot of writing, but the band were back on their feet, back to becoming the draw that would turn their visits to New York into an annual residency at the Beacon Theatre that filled the 3,000-capacity venue for between eight and 19 nights almost every year until their last ever show – at the Beacon – in 2014. That year he was also the recipient of our Living Legend award at the Classic Rock Roll Of Honour in Los Angeles.

The second turning point came when the band were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 1995, and Gregg was so wasted for the ceremony he managed to disgust even himself. Gregg told Barney Hoskyns: “When Willie Nelson brought us up on stage, he turned to me and said: ‘You alright, boy?’ And I said: ‘Willie, I am not alright.’ I was about to fall down, I was so fucked up. I went into rehab the next day. And I did it this time.”

In 2000, in an act that was symbolic as well as practical, Gregg moved back to the south from California, getting a custom-designed home built on a former plantation outside Savannah, Georgia. At last he was rooted. He stayed in that home until his death on May 27. A final Allman Brothers studio album, Hittin’ The Note, was released in 2003, and Gregg was probably right to think it their best since their early days.

Finally, though, the years of less self-control were catching up. In 2007, Gregg was diagnosed with hepatitis C, which he believed came from a dirty tattoo needle. In 2010 he had a liver transplant after three tumours were discovered. He managed a final solo album in 2012, Low Country Blues – a Top 10 hit in the US – but the health problems continued to mount (he had to return to rehab to deal with addictions caused by prescriptions in 2012). The liver cancer returned, and though he kept it quiet – and continued performing until last October – the rumours began to spread. Sadly, they were true.

Gregg Allman was not a cuddly, gregarious man. Nor was he a monster. He was difficult, contrary and troubled. The ghosts that haunted him drove him to do terrible things to himself; they also helped drive people who cared for him away. But without those ghosts he might never have been the artist he became.

He always maintained that talent is not something a musician is born with, but something that has to be learned and nurtured. Equally, though, the almost supernatural ability to turn talent into an expression of pure emotion is not something that can be learned in rehearsal rooms and tight stages in small clubs. It’s a gift, even if sometimes the gift is granted at a terrible cost. Gregg Allman had that gift.

Michael Hann writes for titles including the Guardian, the Financial Times, The Independent, The Economist, Spectator and The Quietus. He was formerly music editor of the Guardian and editor of FourFourTwo. The first band he saw was Samson (opening for Whitesnake), and he is the author of Denim and Leather: The Rise and Fall of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.