Doug Pinnick of King’s X has no doubt where grunge started: “It was through us! We played in Seattle when our first album was released (Out Of The Silent Planet, 1988), and all the musicians in that city were there,” says the Houston hollerer. “The next thing you know, they’re all de-tuning and sound like us – and selling millions!”

Like many others, Pinnick has grotesquely oversimplified the whole grunge phenomenon, because there is no such thing as a ‘grunge sound’. Look at the Big Four of the movement. Stylistically, Pearl Jam are nothing like Nirvana, while Soundgarden and Alice In Chains are completely different again.

“I don’t feel we’re part of any movement,” Pearl Jam vocalist Eddie Vedder said in 1991, as the band’s debut album, Ten, hit hard. “It’s so lazy to lump us in with Nirvana or Mudhoney.”

Grunge was probably the most misunderstood of all musical movements. People tag it with being dowdy and downbeat, promoting surly lyricism. In the process, it is often blamed/acclaimed (make your own mind up) for blowing away the remnants of the 80s big-hair thang.

“I reckon it’s all due to the SubPop label,” Mudhoney’s Mark Arm once sighed. “So many of the bands from that city were on SubPop, and we were all at a similar stage of development. The music business wanted something new and exciting. Did we destroy the 1980s? No. That was pulled down by the fact that there was so much rubbish around at the time.”

Grunge itself might have been born from punk and garage, but coupled to this was the influence of Black Sabbath. And it was probably Arm’s most significant band, Green River, who were the first real grungers.

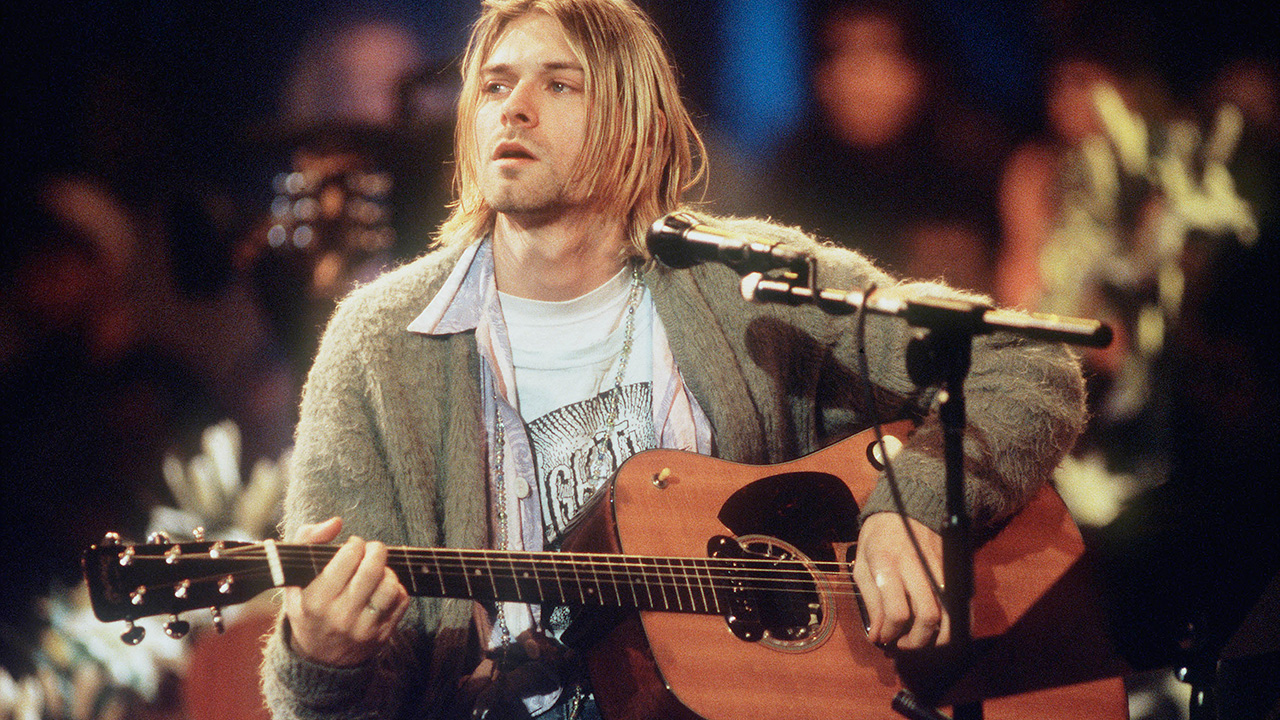

In the mid-80s, Green River were dirty, unkempt and lo-fi, both musically and sartorially, in a period when hairspray and spandex dominated. But by the time the dam broke in Seattle the variety of bands was surprising. Soundgarden were developing from their garage primitivism into a modern hard rock band; Alice In Chains had more in common with King Crimson than with the Sex Pistols; Pearl Jam were fledgling arena rockers; Nirvana worshipped Earth and the Melvins – or at least Kurt Cobain did.

Famed producer Jack Endino – who worked with Nirvana, Soundgarden and Mudhoney – believes that, in many ways, it was the fact that these artists weren’t easy to pigeon-hole that led to the development of the term ‘grunge’: “People just said: ‘It’s not metal, and it’s not punk… What is it?’

The first ‘grunge’ release was a compilation, Deep Six on the C/Z label in 1986. It gave the first serious exposure to Soundgarden, Melvins and Green River – and they stood apart from the rock scene at the time. “Everyone felt there was a connection between all the bands on that album,” Endino adds. “And the whole grunge concept was born.”

It quickly turned from a movement into a trend, accentuated by mainstream acceptance of grunge as a fashion statement, as well as a musical one, as in the 1992 film Singles. And slowly, the more introspective musicians in Seattle, metaphorically speaking, retreated.

Nirvana’s breakthrough with 1991’s seminal Nevermind opened the doors for others. But Kurt Cobain was disdainful of many on the scene, and saved some of his bitterest comments for Pearl Jam. Cobain believed that the latter lacked the underground savvy of Nirvana, and were grabbing a ride on the coat tails of what his band had achieved. However, he rapidly cut back on those comments because of his appreciation and respect for Vedder.

But the most celebrated grunge war of all wasn’t an inter-band one, but effectively occurred within Nirvana itself. In 2001 Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love, went into battle against the remaining two members of Nirvana – Dave Grohl (now with the Foo Fighters) and Krist Novoselic – over ownership of Nirvana’s music. In an effort to gain complete control, Love sued the pair, insisting: “Kurt Cobain was Nirvana. He named the band, hired its members, played guitar, wrote the songs, fronted the band on stage and in interviews, and took responsibility for the band’s business decisions.”

Not to be easily dismissed, Grohl and Novoselic counter-sued, issuing an open letter in which they claimed: ‘Courtney talks and talks about her ‘valuable career’. As far as we are concerned, her career is her own affair, and of no interest to us. Our concern is when she pastes herself into music she didn’t write or perform. By her actions, the Nirvana legacy is becoming tangled up in her own ambitious agenda.”

Eventually a compromise/ceasefire was reached. But that hasn’t stopped Courtney from continuing to lob verbal grenades in the direction of the Foo Fighters leader: “Dave gets to walk away, and be the happy guy in rock. When he’s one of the biggest jerks. He’s been taking money from my child for years!” was one that Grohl was on the receiving end of.

Compared to that conflict, much of the grunge scene has been about as warmongering as spliffed-out pacifists. Maybe this had something to do with the way some of its scenesters bonded in 1991 for the Temple Of The Dog project, which brought together members of Soundgarden and Pearl Jam to pay tribute to Andrew Wood, who died from a heroin overdose in 1990. Wood had fronted Mother Love Bone, which included future Pearl Jam members Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard. The death of the much loved Wood strangely focused the grunge community. It also triggered what was to be a defining part of the scene.

No other genre can have witnessed so much high-profile tragedy in such a short timescale. Both Cobain and Alice In Chains frontman Layne Staley died alone and in agony (in 1994 and 2002, respectively). Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell retreated into an introspective drugs haze to hide from his photogenic appeal. Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder also couldn’t deal with his elevation to rock stardom. Even some of those touched by Seattle, although geographically removed, suffered. Witness the late Shannon Hoon of Blind Melon, who overdosed in 1995.

While overdoses aren’t rare in the history of rock’n’roll, these were somehow different, resulting not from the desire for hedonistic thrill but from desperation. The lyric writing of such talents should have been cathartic. Instead they exposed a vulnerability, which was then fatally exploited by others.

“All these people lining up to say that his [Cobain’s] death was so fucking inevitable. Well if it was inevitable for him, it’s gonna be inevitable for me too,” Vedder said shockingly, soon after Cobain’s suicide. “Kurt’s death has changed everything. I don’t know if I can do it any more.”

Grunge was more about fragile artistry than anything to do with rampant commercialism. It was a lifeline for troubled souls trying to find a way of out of the life’s suffocating maze through their music. And some failed.

“I was shocked how many people related to Pearl Jam,” Vedder once said. “It’s just so fuckin’ weird. You write about this shit, you’re suddenly the spokesman for a generation. Any generation that would pick Kurt or me as spokesman, that must be a pretty fucked-up generation.”