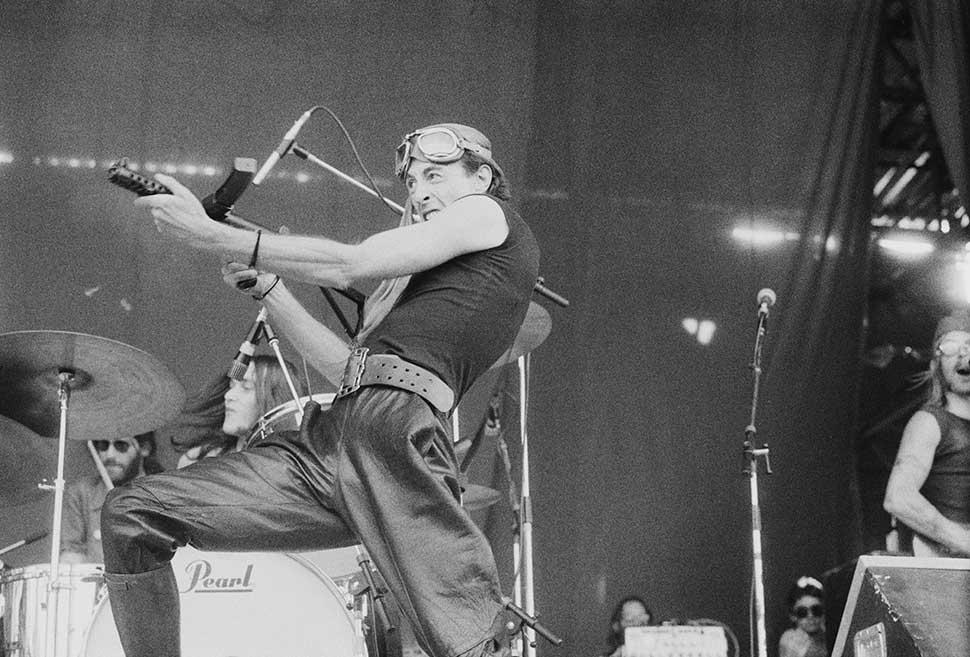

It's October 1977 and Hawkwind are playing the Palais Des Sports, a cavernous dome in the Porte de Versailles sector of Paris. They’re on the European leg of the Spirit Of The Age tour, having already blown through the UK, and frontman Robert Calvert is sinking deep into rock theatre.

This is the new Hawkwind. No more Liquid Len and psychedelia, more a cabaret folie of the absurd. On stage, Calvert transforms into various characters to suit the songs: flying helmet, goggles and commando togs for the crazed military advisor of Master Of The Universe; top hat, frock-coat and chains for Steppenwolf; Lawrence Of Arabia gear and a pair of swords for the oriental killer of Hassan I Sahba.

Calvert has buried himself so fully into this last persona that nothing else exists right now. What boundaries there were have been crossed long ago. Now he is that murderous assassin of Allah, singing: ‘Death unto all infidels, in oil/Guide us o thou genie of the smoke.’ His bandmates have sensed things have taken a sudden turn for the macabre as he sidles over to bassist Adrian Shaw.

“Bob freaked out really badly in Paris,” recalls Hawkwind perennial Dave Brock. “He tried to cut Adrian Shaw’s head off with that sword on stage, right in the middle of the song. He’d really gone nutty by then and we saw what was going on. I mean, he nearly actually did it. He put the sword right across Adrian’s throat.”

Jeff Dexter, then Hawkwind’s road manager, saw it coming too. “Robert got carried away with the idea of urban guerrillas,” he explains. “At that Paris gig, he was totally convinced that the whole first row was full of the heads of the Red Brigades, Baader-Meinhof and everybody. He got completely carried away with that fantasy.”

It all came to a head, luckily not Shaw’s, after the show. “Backstage there were all these people Calvert thought were the leaders of every terrorist organisation in the world,” Dexter continues. “They didn’t have a clue what he was saying, but they were all enjoying it because he was making such a fuss of them. The rest of the band had already run away. They couldn’t handle it at all.

"When I eventually said to him: ‘Look, we’ve got to get out of here and all these people have got to go’, he went completely nuts, pulled out his sword and ran for me. Fortunately I found a piece of four-by-two that belonged to the stagehand and whacked him over the head with it. That’s when he fell to the ground.”

If you thought all Hawkwind’s freaky stuff belonged to the early 70s – that astro time-trip of Silver Machine, space rock and ‘exotic dancer’ Stacia – then think again. Likewise, if you thought, casual listener, that Hawkwind were a spent force once Lemmy had been slung in the clink for a spot of drugs bother on the Canadian border in 1975, or when founder member Nik Turner was dumped 18 months later, then you’re wrong.

Punk-era Hawkwind, which also budged aside for noteworthy offshoot The Hawklords, coughed up a trove of unusual and unexpected goodies. And some very real madness. It was a time of upheaval, of sackings and counter-sackings, of strangeness, quark and gun-raids. Of bust-ups, bitterness and Ginger Baker.

At the heart of the band’s resurgence in the late 70s were Calvert and Brock. Calvert, who had left the band in 1973 for a couple of solo projects, returned to the fold as frontman at the Reading Festival in August 1975.

Steeped in the works of Herman Hesse, JG Ballard and Roger Zelazny, his complex, highly literate sci-fi songs meshed with the new, leaner sound of Brock’s guitar for the epic Reefer Madness, Kerb Crawler and the gothic futurism of Steppenwolf. These were the high spots of 1976’s Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music, Hawkwind’s first album for new label Charisma and under the management of Tony Howard, whose other clients included Marc Bolan. Yet not all liked this fresh musical turn.

“Paul Rudolph from the Pink Fairies came in after Lemmy,” says Brock. “He was a good guitarist, much better than me, and my confidence sank down to my boots. The band ended up sacking me after having a meeting in London in 1976. I suppose this was about nine months after they’d got rid of Lemmy. They did it in the office of Tony Howard, who was looking after us with Jeff Dexter.

"I got a phone call from Bob Calvert saying: ‘We’ve just had a meeting and the band decided to give you the sack. But I disagree with it, so I’m coming down to see you and we’re not going to stand for this.’ So after Bob came over, I went to Tony’s office and then we decided to sack all the people who had organised the cull!”

One of the casualties was the freewheeling Nik Turner, who had been with the band since their first gig in 1969. Others to go were Rudolph and drummer Alan Powell. It was a purge that irked management.

“Hawkwind was the worst job I ever had,” recalls Dexter, still smarting at the memory. “Working with Dave Brock was like being married to the devil. Calvert was nuts, but he was a sweetheart. All this hippie-trippy shit and brotherhood is not in Dave Brock’s vocabulary."

“When we took on Hawkwind, we did it at the behest of Nik Turner. Tony and I really liked him, he was a lovely character. But within a month or so of us taking them on, we discovered they had debt left over from before our time. Brock fired Nik Turner. Nik was a major part of the band, the whole sound and the scope of what they were doing. He was a star and I don’t think Brock liked that. I thought they were great friends but I learnt very fast that wasn’t the case.”

The tours of 1976 and ’77 were a startling spectacle. Calvert’s theatrical performances played out before the backdrop of Atomhenge, a huge molecular stage prop made from fibreglass.

“It was maybe 15ft high with arches all joined up,” laughs Brock. “And the whole thing lit up from the inside. Some of it was actually used for The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, when it was on at the Rainbow Theatre. It was a nightmare to transport.”

The music was rich too, nervy new-wave paranoia that sounded more like the punkier end of Neu! or the mutant strains of early Roxy Music. 1977’s Quark, Strangeness And Charm, inlaid with Calvert’s thoughts on genetics, nuclear war and Islamic Fundamentalism, was hailed by the NME as a triumph of ‘battering ram riffs and monoplane synthesised drones’. Says Brock: “Our music was always quite aggressive, with lots of chunky chords. With punk around, it fitted in. It was almost like going back to our roots.”

The title track was a killer single, but it also introduced the classics Damnation Alley and the tour de force Spirit Of The Age, about a space traveller cursing his girlfriend’s dad for refusing to deepfreeze her for his return.

Calvert, diagnosed with a bipolar condition, was becoming increasingly unpredictable. On tour he became manic, staying up for nights on end, devouring books on guerrilla warfare and how to set up your own private army. He even took to wearing his combat suit off-stage, replete with gas pistol at the hip. Paris ’77 was the tipping point.

“There was also the gun incident in the hotel,” recounts Brock. “Bob used to do a version of Russian Roulette, where he’d recite one of his poems, put the blank bullet in the chamber, spin it and put it to his head. Then, click! Anyway, he was spouting off about the Baader-Meinhof gang in the hotel bar at five in the morning.

"The rest of us were all in bed. There just happened to be a plain clothes policemen in the bar, listening to Bob, and he believed what Bob was saying about being a member of the gang and having weapons in his room. Bob, who shared a room with me, had also said my guitar case had a sub-machine gun in it.

“At six in the morning there was a thumping at my door. Two police officers came in and had me up against the wall at gunpoint. I said: ‘What the hell’s going on?’ Of course they opened my bag and saw the Russian Roulette pistol and the guitar case. By that time, with all the commotion, Jeff Dexter had come along to sort things out. But then they saw Bob’s clothes – all commando gear – which wasn’t a great sign either.”

Jeff Dexter claims he was left to sort the mess after the Palais Des Sports debacle. “We were supposed to be going on to Belgium to do three more gigs but the rest of the band all got up very early the next morning and were all ready to split without telling me and Calvert. They were all packed to go.”

There followed the bizarre sight of Calvert, shaven-haired and in full commando gear, chasing the band’s silver Mercedes through the streets of early-morning Paris.

“All the passers-by stopped dead,” he recalled later. “It was like a scene out of Alphaville… [the band] were showing me that they were fed up with the way I was carrying on. We had a big fucking argument. They were pissed off.”

Brock says the band had no option. “Bob was so nutty at the time that we called the rest of the tour off. He was sent back on the plane with Jeff Dexter, who he tried to strangle on the flight [incidentally, Dexter denies this incident]. When they got back, Jeff had to put him in a sanitarium.”

Calvert received treatment and rejoined Hawkwind in the studio in early 1978 for what would become the semi-live album, PXR 5. Then they headed off to the US in March. This time he was at the other extreme.

“On the American tour Bob was completely the other way,” remembers Brock. “He was very quiet. That tour was the end, really. We felt like we’d reached the end of one of our trips.”

Dexter agrees: “He still performed really well but was very subdued the whole time. He kind of went into his shell. But I remember them going down very well in the Midwest. They could really turn it on. There was a gig in Philadelphia where they were amazing. For an audience of Midwestern hippie freaks, it was perfect shit.”

The tour ended in acrimonious fashion. It was the end of the road for Dexter and Tony Howard. “It was after the San Francisco gig,” says Dexter. “Tony and I told them we didn’t want any more to do with them. So we paid them off, gave them all their airline tickets and left for LA. Ten days later I was driving when I saw this guy in the middle of the street, flagging me down. It was Dave Brock. He said: ‘I’ve got no money and no tickets.’ He’d spent his money and sold his tickets.”

The band had splintered, but Brock and Calvert regrouped on their return home. To side-step any legal issues, they formed The Hawklords, adding Steve Swindells on keyboards and bassist Harvey Bainbridge, both of whom had briefly gigged with them as The Sonic Assassins.

The sessions, which took place in a Devon farmhouse in the summer of 1978, yielded 25 Years On, a conceptual LP based on the saga of Pan Transcendental Industries, a global corporation intent on replacing angels’ wings with car doors. Luckily, it’s way more accessible than it sounds. Calvert and Brock were back to their free-flowing best, and it was as far from the band’s crusty Ladbroke Grove beginnings as you could imagine.

“Robert was in a very rich vein of work at that time,” says Bainbridge. “When we did the Sonic Assassins gig, we did this piece that was eventually called Over The Top. Basically it was just a jam, but then Robert came out and did this spiel about being in the First World War trenches. And I think he really was in those trenches at the time. He sank himself into these characters.

"On the Hawklords album I had this riff and Robert just sat there and wrote Free Fall, off the top of his head. Working with Robert and Dave Brock, who I think is one of the best rhythm guitarists this country has ever produced, was fascinating. To me it was like playing ‘grown-up’ music. I remember reading a review in Billboard magazine, who described it as Hawkwind like you’ve never heard before, with four-part harmonies and the like. They even called it AOR!”

The resulting tour was an elaborate confection of paint-splattered jump-suits and complex stage rigs, based on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, designed by Hawkwind’s artistic genius, Barney Bubbles.

“There was a huge scaffolding rig with spinning mirror-wheels and six dancers. It was incredible,” says Bainbridge. But it was also time for another shake-up. Drummer Martin Griffin was fired, Swindells left and an increasingly paranoid Calvert quit to concentrate on writing.

“Bob was great to work with,” asserts Brock, “but he’d have his freakouts. He was hyperactive and it was quite stressful when he was over the top because he just wouldn’t sleep.”

There was time for one last hurrah during this purple patch of Hawklore. In 1979 Brock reformed Hawkwind with Bainbridge, Simon King, ex-Gong man Tim Blake and guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton. After the Live Seventy Nine album, Ginger Baker joined the party for 1980’s sorely underrated Levitation.

“It was one of the first digital recordings,” explains Brock. “It gave a clearer tone to everything, but we were all a little in awe of playing with Ginger, who was this world-famous drummer, of course. He stayed with us for a year and a half. He was a pretty easy-going character.”

Bainbridge doesn’t quite remember it that way. “On the previous tour, Ginger said he wanted to cut the light show out, so we’d get more money. No one said anything, so I stuck my neck out and said: ‘Well, I don’t think it’s a good idea. The whole point of a Hawkwind show is the lights and spectacle.’”

At sessions for 1981’s Sonic Attack, Baker and keyboardist Keith Hale “told me I ought to leave. But how it turned out was that Dave and Huw decided it was Ginger who ought to go, but I had to tell him! Keith Hale ended up going with Ginger too. A bit of a grumpy man is our Ginger. It was a happier camp afterwards.” A seething Baker allegedly quipped: “The world’s worst bass player sacked the world’s best drummer.”

Huw Lloyd-Langton remembers them both playing Glastonbury shortly after the dismissal: “Ginger played the night before and made some snide comment about Hawkwind. So somebody from the audience threw a brick at him.” Hawkwind, as is their DNA, have pressed on ever since. They still operate in that same punk spirit that gathered them admirers from John Lydon and Joe Strummer to Jello Biafra, Henry Rollins and Primal Scream. Robert Calvert tragically died of a heart attack in 1988, aged just 43, but Dave Brock is still there at its core.

“Dave’s influence has always run through Hawkwind,” said Lloyd-Langton, who died in 2012 after a two-year battle with cancer. “As long as Brocky exists, there will always be a Hawkwind. It’s a strange, funny old band, but it just wouldn’t happen without him. He’s been the headstone of it all.”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 135, in July 2009.