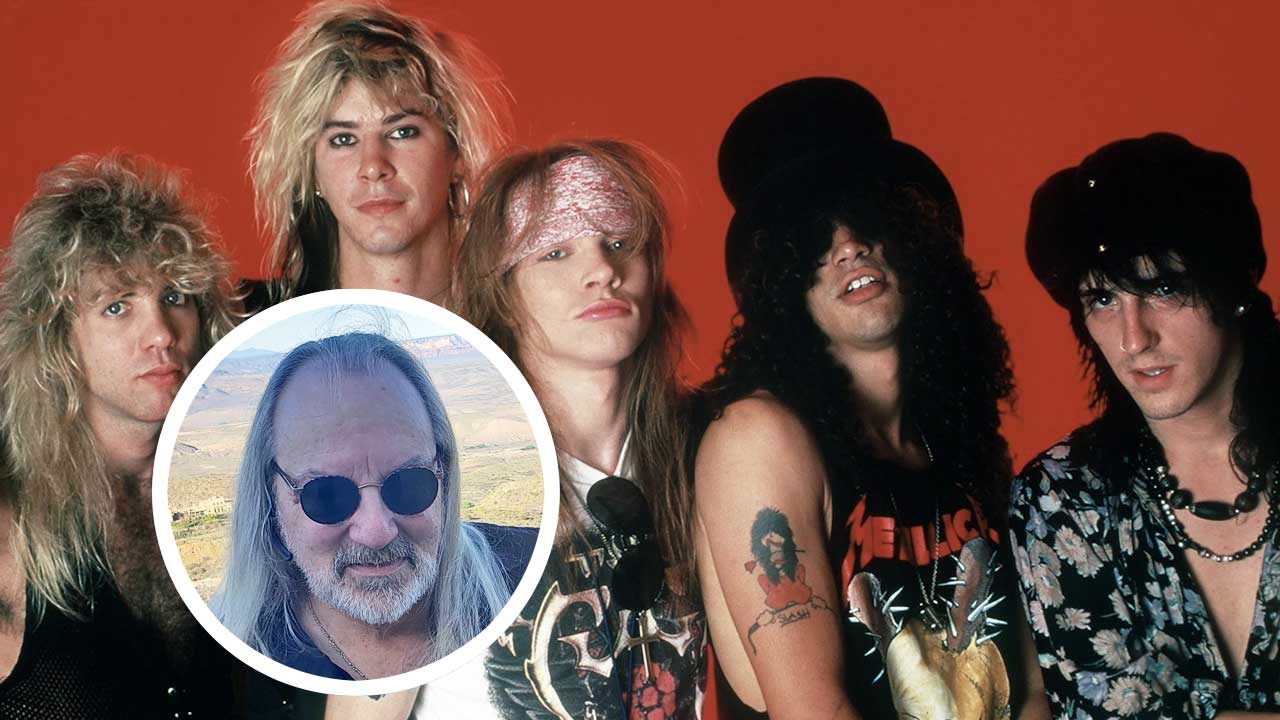

As manager of Guns N’ Roses from 1986 to 1991, Alan Niven not only kept the wheels on hard-rock’s most chaotic band, but spurred them to their most creative streak.

Appetite For Destruction and both Use Your Illusions were recorded on his watch – and perhaps it’s no coincidence that after Axl Rose dropped the axe, the band entered a period of studio stasis from which they have never truly emerged.

Almost four decades since he took the toughest job in rock – and 35 years since Appetite – the man Slash described in his memoirs as a “charming, raffish New Zealander” shared some early memories and thoughts on the reunited Gunners.

You replaced Arnold Stiefel and Randy Phillips as manager of GN’R in 1986. How did that opportunity come about?

Randy and Arnold wanted out in the worst way. They had rented a house in The Hills for the band and it was beginning to show signs of Gun wear. A toilet was dumped outside the front door. There was a python in the bedroom eating white rabbits.

Frankly, I cannot imagine the Sunset style of Randy Phillips ensuring any real connection with the band. Further, they were a typical 10 til 4 kind of operation.

For me, rock ‘n’ roll was a way of life. It’s 24/7/365. So when I rolled up on my bike, [then a Kawasaki Vulcan – I had yet to be able to afford a Hog], the band knew that they would be dealing with someone saltier, with both feet on the ground. No bluster and no bullshit.

Stiefel and Phillips wanted out. Fast. And Tom Zutaut [Geffen A&R] was utterly desperate to find a manager, any manager. Rosenblatt, the President of Geffen, refused to allow them to begin recording until they had one, and they’d been rejected by everyone, including myself, twice. On the third time of asking I told Tom, I’d meet and see what happened. Only Izzy and Slash turned up for the meet. Izz nodded out at the table. The needle and damage being done.

Which left only me and Curly. And I liked him. He was articulate. Very charming. I was intrigued. Enough to go and see what was going on in Pasha Studios. I was asked to sit in on the mix. The bayou began to rise up over my boots. I began to get sucked in.

What is different about Slash to other guitarists? How long did it take you to realise that he was special?

When I first met and listened to Slash there was the impetuousness of youth – lots of energy and even more notes.

I first thought he might be beyond average when I asked him what he wanted from the band, from his playing – “I want to be recognisable” he said. He wasn’t referring to a top hat , he was talking about developing a personal style that could be recognised. Think of Santana. Think of Robin Trower. Think of Peter Green. All have their feel and sound. Predominantly determined by their left hands.

Guitar is a voice – it’s not how many words you use, but how you deliver the right ones with dynamic, and clarity. Great speakers know when to pause. Great players revere the space between their notes. Great guitar players learn how to manipulate a sustained note into personal representation.

Slash didn’t say he wanted a house, an endless stream of girls, an Aston Martin. He wanted to develop his technique so that it would have an identifiable character. That’s an intelligent and special musician.

During the recording process for Appetite for Destruction, what was Slash like? Do you have any memories or stories of how he would be in the studio?

The most memorable moment was when he smashed an SG through the windscreen of the rental van Guns used to get to the studio —a clear and obvious indication he was having sound problems. As you can find on the [inter]net there are many notices of how I found and gave him his AFD guitar, which, to this day, he states is the one guitar he’d keep if he were to only have one.

He and Mike Clink did great work together. Having done a lot of recording with Michael Schenker, I knew Mike would be patient, get great tone, and work at constructing memorable, melodic statements with Slash. History proves my confidence in them working together was correct.

What was Slash like in this period?

Inebriated. Excited. But truly focused on what he was recording.

Appetite for Destruction celebrated its 35th anniversary this year. Did you or any of the band members have any idea that it would go on to be as successful as it was, and did you think that after all these years it would still be adored by so many?

No. And if anyone claims they foresaw the future they are liars. Or certifiable. My best estimate was, ‘if I can keep them alive’ and ‘if I can instil a minimum of professionalism’ then after a while we may have a great underground record that reaches the gold standard. Keep in mind Never Mind The Bollocks did not go platinum in the US until Appetite For Destruction generated greater interest in the Sex Pistols.

Did you feel there was a lot of pressure going into the Use Your Illusion era following the success in the previous few years?

We’d sold over 8,000,000 units of Appetite in the U.S. by the time Use Your Illusion took shape. There was unbelievable pressure on everyone. As much as we would say ‘ignore expectation and just do what you do’, alone, at night, I know it pressed down on our consciousness. On top of that I’d have a belligerent David Geffen in my face, within inches … “when am I gonna get my record?” “When it’s fuckin’ done David.”

His hard stony eyes stare at you, and then he walks off in silence. He had to accept that I had saved a disastrous signing and that I would, eventually, deliver. No one else would. Just consider that they have delivered nothing for over thirty years. Chinese Demos is not a GN’R record. It’s a Rose solo record.

How did the cover of Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door come about? Did you feel that it was a risky move covering a Bob Dylan hit?

Geffen wanted a track from Appetite for the soundtrack of the Tom Cruise movie, Days Of Thunder. I made some phone calls and found that the movie was not that good. I am not a fan of Scientology either. I was also reluctant to overexpose at that time. I told him ‘no’. He, predictably, went ballistic. We screamed down a telephone line at each other. Once my disposition had balanced my thought was ‘he brought us to the dance, so he deserves a twirl.’

I called Axl and told him about the row, and what my thinking was. I suggested we record something other for him. Axl suggested Door. They had been playing it live in memory of Todd Crew – who had been working as a bass tech for Duff, and who died of a heroin overdose. I thought that an excellent idea – everyone sings Dylan better than Dylan – especially Axl.

What are your own favourite Slash or GN’R stories from the early years? Which songs and guitar parts do you like best?

Well, there was this one night that he called and asked if I wanted to go with him to see Albert Collins. It was a Friday. I got home Sunday afternoon. At one point we went to The Palace. I lost him and could not find him anywhere. I looked high, low, and lower.

Eventually, I decided there was only one place I hadn’t looked. I went into the women’s bathroom, and, voila, there he was, sitting against the wall, on the floor, caressing a fifth of Jack [Daniels]. I understood the logic – if you wanna meet a girl and in a non-competitive circumstance, where else would you go?

Songs? Parts? What I like most about Slash are the moments when he steps off the cliff and plays in the moment, something unexpected and entirely spontaneous.

You previously said that if you were to do something different during your tenure with the band, you would not have signed the contract in September 1986. Is there any specific reason why you feel this way?

Guns consumed soooo much of my energy. I have no doubt Great White woulda had a bigger profile had this not been the case. I took Guns from the streets to selling out Wembley. There was no gratitude whatsoever from Axl. Who, every now and then, I would have to work against. Iz, Slash and Duff would sometimes call and say “have you heard what he wants to do now Niv? Y’gotta nip it in the bud.”

One prime example is that Axl refused to do the Aerosmith tour. He told me to cancel. I had signed a contract with five individuals collectively known as GN'R. My responsibility was to the whole, to the entity, not the lead singer alone. I refused. He was pissed. Banned me from the tour for three weeks by which time everyone knew it was going great and the then highpoint of the band’s career.

I had to send cops to his apartment to drag him and Erin down to the Coliseum to perform before The Stones. Again, he wasn’t happy, but it ended up being a triumph. I have no doubt he has been an impediment to other projects – UMG [Universal Music] will do anything to get something, anything, from Axl, even if that means I get ignored.

They took prime energy out of my life, and gave very little back – they still owe me for the Adler court case and for paying for their tour manager. Users are not friends. Not family.

Do you still keep in contact with Slash nowadays? How does it feel to see Axl, Slash and Duff onstage for the reunion tour – and what are your hopes for a new GN’R album?

Slash and I used to keep in contact – he even came and played a benefit in our little Arizona mountain town – but since the reunion, we have drifted apart. Axl is a canister of resentful and unappreciative bile, and it’s best to hope the lid stays on, I suppose. I used to send him books to read on tour – Balzac, Russ Baker, Tolstoy, Colin Wilson, whatever…

I have no interest in seeing the band again – their moment was February 2, 1988 [the date Guns N' Roses: Live at the Ritz was filmed]. The Aerosmith tour was really good too – tremendous band response to tremendous audience response. I have no hope of, or interest in, a new Guns N’ Roses album… the tantrums of youth look absurd on a 60-year-old. It’s a shame they have been creatively impotent since 1991.

The super deluxe editions of Guns N' Roses' Use Your Illusion I & II are out now.