With his thatch of black hair, white T-shirt, boots and baggy khaki combat trousers combo, it’s difficult to believe that Jeff Beck is 72. And, notwithstanding the endoscopy and short hospital procedure he endured in 2014, by all accounts the legendary guitarist is in peak physical form. “I’ve got the lungs of a twenty-three-year-old,” he boasts breezily after watching me almost pass out in his kitchen-diner from the exhausting four-flight trudge up the stairs to his flat in an elegant vintage building in leafy West London. He recently had a health check, during which he nearly blew the ball out of the top of the breath-measuring gadget. Still, fit or not he always takes the tiny, somewhat rickety lift.

While he’s making tea, the buzzer goes – it’s two guys from his label. One is full of praise for Beck’s excellent, powerful new album, Loud Hailer, his first for six years. Which seems to please the guitarist no end. The other arrives with a manuscript, which he plonks down on my lap. Published concurrently with the album, Beck01 is a biography-cum-pictorial survey of his mercurial, wayward career, from his stints with The Yardbirds, the Jeff Beck Group, Beck, Bogert & Appice and solo, through his many musical changes, plus his famous passion for hot rods. It’s a hefty tome, a lavish, limited-edition affair, hand-bound in leather and aluminium with each copy numbered and personally signed by the author. Even the foreword, by John McLaughlin, is grandiose – in it, the Mahavishnu Orchestra virtuoso proclaims Beck his “all-time favourite guitarist”.

Beck notices that I’m listening intently to the conversation, and only distractedly leafing through the book – and have it on my lap upside-down. Cue guffaws all round.

“Actually it’s par for the course with my career,” Beck notes drily. “Makes perfect sense upside-down.”

In which spirit it makes sense to start at the end, or at least the present, with an examination of the new album. Loud Hailer is Beck’s first record with singer Rosie Bones and guitarist Carmen Vandenberg, two young musicians he met by chance via Roger Taylor. It was at a birthday lunch for the Queen drummer that Beck was introduced to Vandenberg. Later he went to see her in concert with her musical other half, collectively known as Bones, and he was “blown away”. He knew immediately that they would form his latest band. With Bones’s ferocious blues wail and Vandenberg’s fierce guitar playing in place, the line-up was completed when Bones associate Filippo Cimatti brought in Giovanni Pallotti (bass) and Davide Sollazzi (drums). Production on the album was by Cimatti and Beck.

The results are viscerally impactful: Loud Hailer is a riot of sci-fi shredding and future-blues atop a range of primal but electronically enhanced beats – Beck is no stranger to the technoid pulse, having made Who Else!, You Had It Coming and Jeff between 1999 and 2003, aka The Prodigy Years. Vandenberg and Bones co-wrote, with Beck, its 11 tracks, which include two instrumentals and range from wah-wah freak-outs and heavy electro-rock to eerie atmospherica, with solos both elegiacal and electrifying.

So much for the sonic footings. The lyrical content for Loud Hailer came even more easily than the music, nudged along by a fascination with the events of September 11, 2001 and the web of claims, counter-claims and conspiracies that emerged afterwards.

Beck appears to have spent much of the six-year lay-off between 2010’s Trevor Horn executive produced Emotion & Commotion (incidentally, Beck’s highest-debuting US album ever) and Loud Hailer glued to YouTube. Having outlined his intentions for the album’s subject matter to Vandenberg and Bones, last December they “sat down by the fire with a crate of prosecco and got right to it”.

“The songs came together very quickly – five in three days,” he adds of such incendiary politicised numbers as album opener The Revolution Will Be Televised, the finger-pointing Thugs Club and The Ballad Of The Jersey Wives, about the widows of 9⁄11 victims.

Talking about it today, Beck sounds calm and lucid, less like a deranged conspiracy theorist than like a man on a mission. He spends a good 30 minutes elaborating on the subject, with digressions on, variously, Donald Trump, TV presenter and structural engineer Fred Dibnah and Prince. Jeff Beck: guitar pyrotechnician, psychedelic and heavy metal pioneer, destroyer of amps… and now agent of subversive political truth? It’s a long way from Heart Full Of Soul.

So where does this obsession with 9⁄11 come from?

I just became fascinated by how 9⁄11 was orchestrated, with how utterly preconsidered it was. Then I became enraged: “This has gone on and nobody’s doing anything about it.” Everyone’s just scared of authority. The stuff I’ve seen on there [points at his laptop on the table]… It’s not over yet, folks. Another album at least!

I became riveted by all this stuff. And it’s out there; the news is out there. It’s up to you to cross-check what someone’s saying, look at their faces… I was doing that for about three months, until Rosie and Carmen came along and said: “What are we going to sing about?” How about [clicks fingers] this? And then every day I’d come up with some clip and they’d be just spellbound by these completely convincing statements. They were heartbroken, shocked and tearful when I showed them the footage. It brought out the best lyrics we could on the subject.

Loud Hailer, then. It’s been six years since the last one. Has this 9⁄11 album been gestating that long?

We don’t actually make reference to 9⁄11. The songs are about a general disgruntlement and dissatisfaction with things. Obviously anyone delving past the first lyrics will make that connection, but… When I recruited Carmen to be in the band there wasn’t any design on any vocals, we were going to write instrumentals or whatever. But as soon as me and Carmen decided to involve Rosie and she heard my ideas for songs, it just went [snaps fingers again] rocket-powered. To have Rosie’s voice say what I want to say and to do it in the way she’s done it is very satisfying. I can only do so much with the tone of the guitar. You cannot beat explicit lyrics like those.

Fifty-one years since Having A Rave Up With The Yardbirds introduced this quixotic guitarist to the world, Jeff Beck is still delighting and confounding in equal measure. His last album, Emotion & Commotion, with its Joss Stone team-ups and a cover of opera favourite Nessun Dorma, suggested a man growing old gracefully as he approached his eighth decade. Loud Hailer, by contrast, is the incendiary work of a much younger firebrand. An album of grievances both political and cultural (there’s a poison arrow on the album aimed at the karaoke-pop generation), it’s the last thing you’d expect from Beck – and therefore the first thing he considered doing. Makes perfect sense. Par for the course.

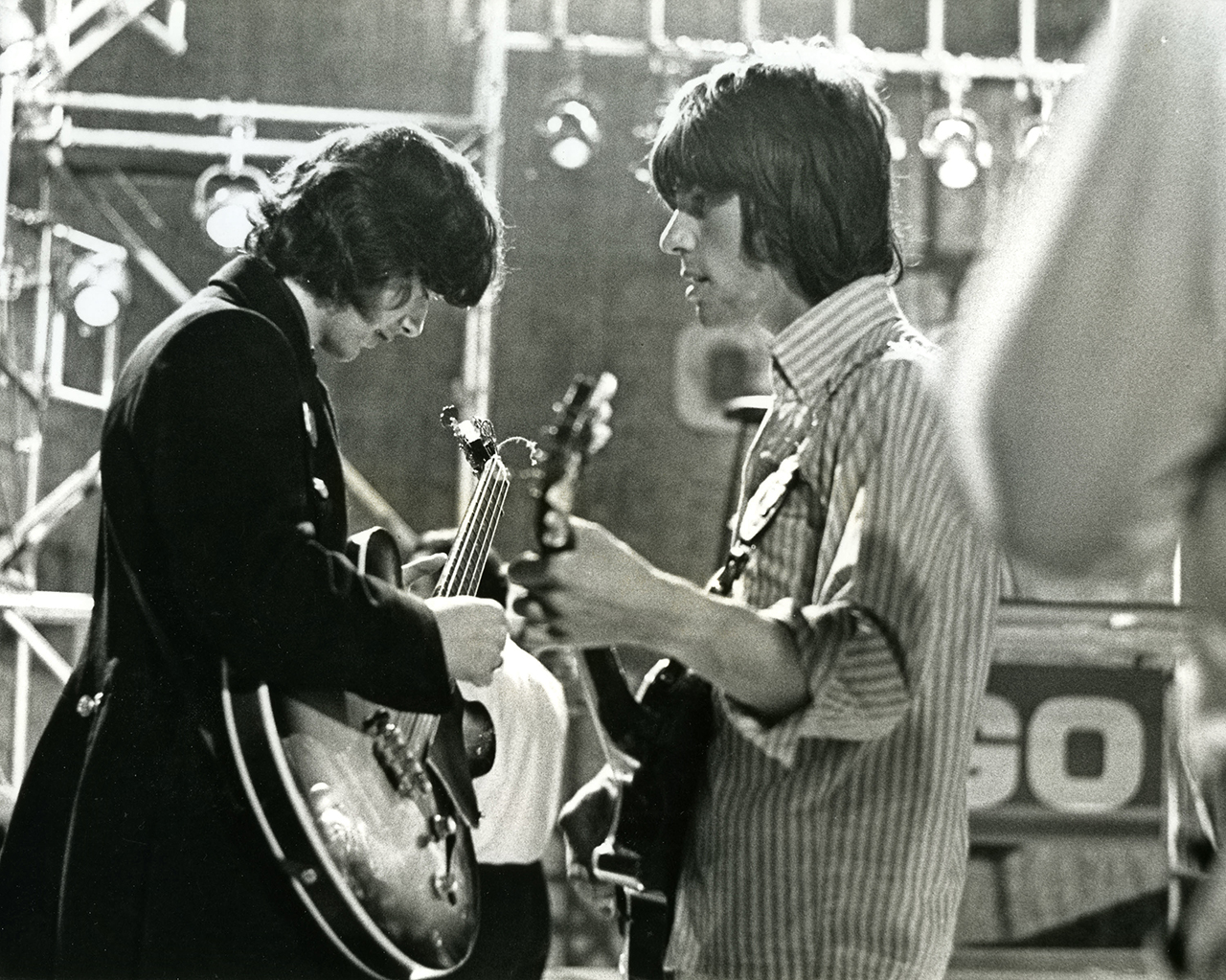

This is probably a good time to change the subject and start rifling, as per Beck01, through his back pages. One defining early image of him is from 1966, from the film Blow-Up that The Yardbirds appeared in at the height of their psychedelic abandon. There was Beck on stage in a club, peeved by a buzzing amp, smashing up his guitar. It was punk, 10 years early. “I was bloody furious,” Beck recalls today.

Where did that destructive anger come from?

I suppose it was the sum total of being mistreated at school; being hammered by a gang. Also, I had a blow to the head. I was knocked off my bike – run over just prior to the 11-plus exam, by the headmaster of Wallington County Grammar, which is the school I would have been taking the exam for! He carried my wrecked bike home and carted me off to hospital. And my mother just freaked. She told me not to go out that night. I was unconscious for about an hour. I had this profuse bleeding, broken teeth, a fractured skull, a broken knee and I kept swallowing buckets of blood.

Were there repercussions?

I don’t know whether it truncated my progression intellectually. I used to beat my uncle at chess when I was eight. He taught me and I whipped him. When you’re alert and reasonably intelligent, that’s the best game ever . I still play chess. Anyway, I heard him tell my dad: “Watch out – his intelligence is uncanny.”

There’s a photo in the book where you look like a refugee from a 2016 boy band.

Oh, the one where I’m eating a custard tart! I’ve got a rockabilly haircut. I had to go to Croydon to get the hairdresser to do it because my mum had alerted all the hairdressers: “Do not do his hair!” I was influenced by Jerry Lee Lewis – I’d just seen one of his films and desperately wanted a crew cut. ”

Do you have a favourite look of yours through the years?

When you’re ugly there’s not much you can do. Just plough on.

You’ve done alright, haven’t you, over the years?

What, you mean in spite of the fact I’m ugly?

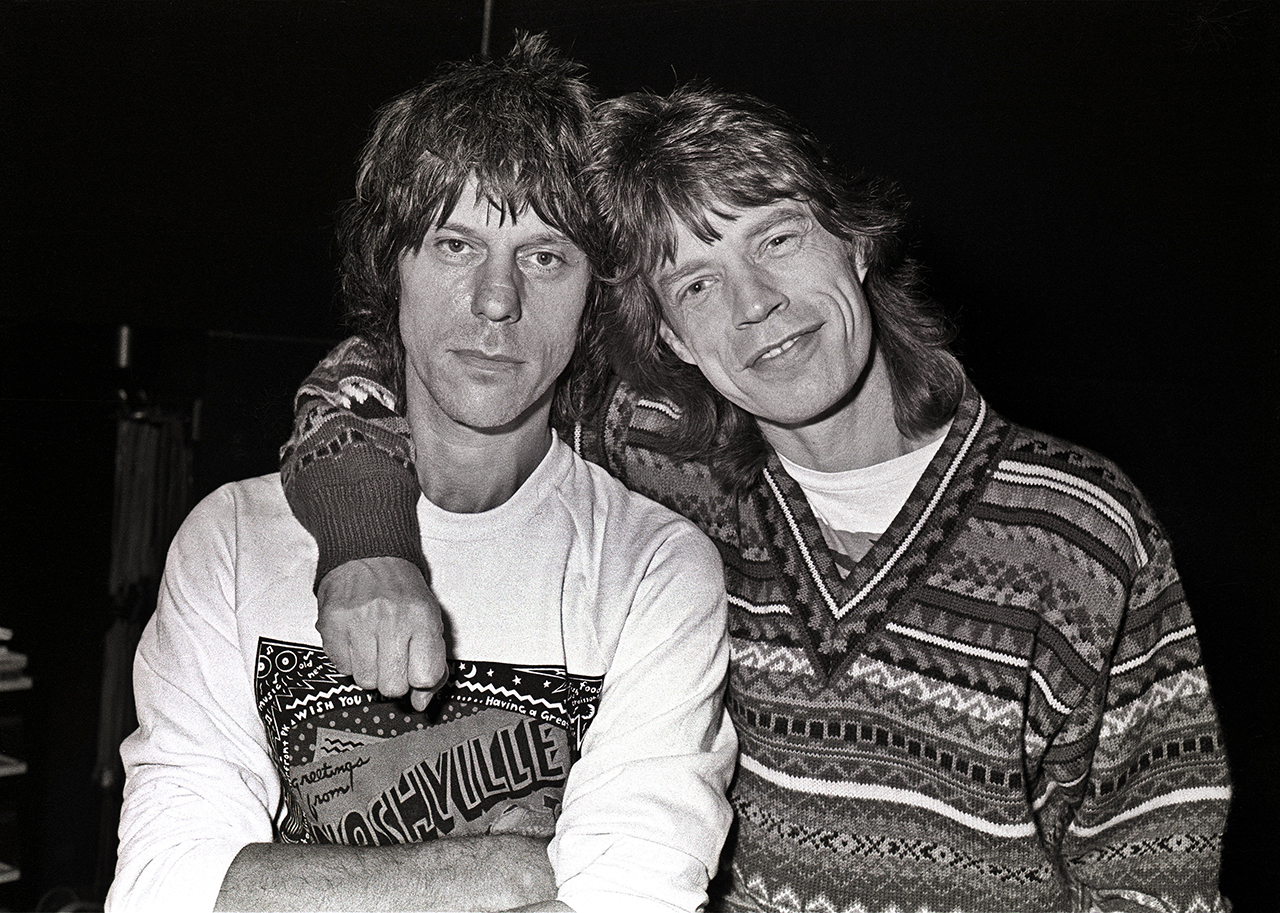

Come on, you used to get mistaken for Mick Jagger!

Yeah, but he’s got more creases than I have. The sunken cheeks were due to the teenage lust for chocolate and sweets, which meant all your teeth rotted.

Your book shows your abiding interest in cars and guitars. How many hot rods do you have?

[Guarded] Enough. It’s an upsetting amount. For those that…

Don’t have?

Yeah. Best not to say. But I built them. Probably two-thirds are built.

And you loved guitars because they were a pathway to the future?

Yeah. The electric guitar was such a futuristic instrument. What I found with the electric guitar was more than just a challenge. It was almost like a lifestyle in a box; you could choose what to do with it. You could shock people. It’s the most powerful weapon. A Fender Strat and a Marshall and you’re kitted out. It allows you expression of all kinds, without the need for a voice.

Did you used to get astonished looks when you were with your early group, The Tridents, because of all your mad sci-fi sounds?

Oh, absolutely. It was open season. I used to slacken off the lower E on the guitar and do Bo Diddley stuff, just a jungle rhythm with maracas; a very tribal-sounding rhythm. I loved that. We’d do a verse, then I’d do a twenty-minute guitar solo where I’d just go nuts and do backwards stuff and feedback and play two guitars at once… And then Hendrix comes along and, you know, upturned the whole apple cart. I was doing great and I was getting known as an experimental guitarist with The Yardbirds, and then Hendrix stomped all over everything. It’s like, the more time goes on, the more astonishing he seems. I saw him first in late sixty-six, in a tiny club, and that was the moment of reckoning. “Bastard! You’ve blown my head away with the best playing I’ve ever heard.” I suddenly realised when I went to walk out: “What do I do now?”

Up until Hendrix’s arrival on the scene, what would you put your name to? Feedback? Distortion?

Yep. Feedback was this thing that in 1960 I was trying to get rid of! I loved the feeling of power of playing to an audience, but I never thought I was loud enough, because drummers were so loud and all I had was this poxy little five-watt amp. So I’d play a feedback note, and everybody started to like it. So I turned adversity to my advantage.

Could Hendrix have happened without your exploratory techniques and innovations?

Who’s to say? The thing that put a nice big sticking plaster over the wound after seeing Jimi was that he knew who I was. And he actually copied a couple of my Yardbirds phrases. That was enough to help me keep my chin up. And he would recognise me whenever we were playing, whenever we visited a nightclub. I would see him and say: “Hey,” but I never wanted to look as though I was a freeloader. Everybody would sit round Jimi [and worship him].

Still, a couple of things have been at least partly ascribed to you: psychedelia, say, or heavy metal.

The Yardbirds gave me this job: a licence to annoy, a licence to shock and do what you like. They recruited me as a replacement for Eric [Clapton] – maybe temporarily, he may come back. But I was like, if I get in there he ain’t coming back! It wasn’t an easy pair of shoes to fill, I can tell you. So they looked at me not to be like Eric. I said: “I’m not like Eric anyway. He plays the most amazing blues; I don’t want to do that. That bin is empty to me.” If I want to hear slide I’ll listen to Earl Hooker or Muddy Waters. Eric’s the great British exponent of that – let him have that. I want to go and make crazy sounds; sounds that are there for the taking, just by the use of simple equipment.

What would you cite as your major breakthroughs?

[Sighs] You could probably come up with a better answer for that than I would. I don’t really wonder about what I’ve done. There’s no time to reflect too much. There’s the raga bit in the middle of [The Yardbirds’] Shapes Of Things. That whole thing was outrageous anyway, because we were in Chess Records when we did that. The guys in there thought we were totally nuts. They said: “We’ve had the Stones in here and they were nothin’ like you guys.” I said: “Thank you!” Keith [Relf, singer] was totally nuts. The thing that I dearly miss, even today, is the surreal humour we had. That played a massive part in what was created. The intelligent humour was far-reaching.

How about Beck’s Bolero (landmark 1966 instrumental that Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, Nicky Hopkins and Keith Moon all played on)?

Yeah, Bolero especially. That afternoon was so quickly over with. Moonie turned up, and I never expected it, because he was so scatty and you never knew if he was going to show. But once he was in there, we started it off and I went and heard the playback and went: “Jeez, this is the beginning of something amazing. You guys are not going anywhere.” Page on rhythm guitar, me on lead, John Paul Jones on bass – it’s done! We were at IBC Studios in Langham Place, and to cap it all we had Glyn Johns engineering. This is the motherlode! And the next day it was all over.

Of the guitarists generally ranked in the lists of all-time greats, Beck is arguably the one who didn’t achieve all his promise, whether critically or commercially. But these things are relative – he is, after all, widely venerated, the one other guitarists most likely pick as their favourite.

We’re also talking here about someone with a pile in Sussex, a collection of rare cars and an expensive flat in London. But clearly the superstar success of his former compadres still rankles. Particularly Rod Stewart, because Beck felt the pang of betrayal when Stewart left the Jeff Beck Group to form the Faces; and Jimmy Page, because as far as Beck (and, to be fair, many others) saw it, Led Zeppelin based a lot of their shtick on what JBG did on their 1968 album Truth.

“First I had to deal with the Jimmy thing, and Zeppelin, and then Stewart,” he groans. “All these people I’ve been involved with were making massive wages and I was doing nothing. And I had to accept that.”

You’ve talked before about your frustration at never quite realising the sound, the ideas, in your head. Did you really feel that even with the Jeff Beck Group when they started to take off?

Yeah. But I have to be grateful that I didn’t succeed, because you’re then lashed to the whipping post. I wouldn’t swap places with Jimmy. As much as I’d have loved to have been in Led Zeppelin and enjoyed all those amazing shows, in hindsight I’m much better off being a scout, going out in the field. That’s what I see myself as. Ironically, Page had an album called Outrider – and I was the outrider. I never, ever envisaged having massive success. And I’m glad I didn’t, otherwise people would be pointing at me in the street.

Does the Zep thing still annoy?

It’s just one of those things that happened, and no one really cares. If I’m the only one worrying about it, let’s get over it.

If you were in a room with Jimmy now, would that come up in conversation?

No [softly, but with force]. He knows what happened and I know what happened. I’d love to tell you… But things have settled… They did what they did and there’s no way you can say anything, really.

But surely it’s nice to know you provided the catalyst for one of the biggest bands in history?

If you think so then that’s all perfectly right. It’s not me saying that, though.

In the final stretch of the interview, Beck covers a lot of ground. He talks about the time he briefly considered stepping in, after Hendrix died, and doing something with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding: “But it wasn’t quite right. No one’s going to accept me in the place of Jimi with those two.” There was the mooted role filling the gap left by Syd Barrett in Pink Floyd: “I don’t know whether I would have coped with the ‘upbringing’. They were probably slightly too upmarket for me.” He talks about getting stoned with Bob Marley and winding up sitting in the middle of the road, in deepest Surrey, clueless as to how he got there: “It messed me up. That’s the last time I took [marijuana].” And he remembers passing on the offer for the Jeff Beck Group to perform at Woodstock.

“I break out into a sweat thinking I could have been on that bill,” he says, his own harshest critic. “It was one of the best things I ever did. Because I would not have wanted to have been on the split screen, preserved forever and a day on film, with the condition of the band the way it was. We were okay – we were a small dance-hall-type band. Clubs? Yeah, fantastic. But to play in front of 250,000 people? I don’t think Rod was mad enough for it, and I certainly wasn’t able to get out there and… after what, the Mamas And The Papas? Jesus. Every huge act was there. We’d have just been made mincemeat of. I thought it was the best thing not to do it.”

Beck agrees that this has, in a strange way, been a saving grace – never to have been fixed to a specific landmark moment. Asked whether he has a happiest time looking back, he ranges over his chequered career.

“To have George [Martin, producer of 1975’s Blow By Blow and 1976’s Wired] interested was a blessing,” he says. “It gave me wings I never thought I had. That album [Blow By Blow] was really a turning point. When Epic heard it, it opened up the doors. It was red carpet, you know. Following it was difficult. On Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop [1989, regarded as one of his best] there were melodies so rich I had trouble not crying. In the nineties I could see that rave culture was affecting people and that they would listen to any music, any mind-numbing groove. I had fun with those [90s] albums but they were more or less fillers. It wasn’t the right time for me to release anything of any depth or political spin – they would have just got lost. Because they were signing up acts that I wouldn’t piss on if they were on fire. They were necessary contractual things. With Emotion & Commotion I made a real concerted effort to try to make an album with music that had some credibility to it.”

In August this year, to commemorate blues legend Buddy Guy’s 80th birthday and celebrate Beck’s 50 (actually 50-plus) years in the game, he will be performing at the Hollywood Bowl. The set will cover the waterfront. “It’ll be fifty years condensed into one pot,” he explains. “I’m going to have to be clever how I choose, because I don’t want to rob too much from any one genre or era of music. I’m still thinking about the best fast-flowing show that will leave people going: ‘Fuck my boots! I’ve just been through fifty years in two hours!’”

And he’ll be doing it without the aid of stimulants – Beck has never been one for drugs, unlike most of his peers.

“I never liked not being in control,” he reveals. “Every time we went to a club, the unwritten law was, afterwards: “Whose house are we going to go to [i.e. to get stoned]?” How shallow and pointless. Do something! Let’s go out and race! Enjoy something!”

Beck might have smashed a fair amount of equipment in his time, but his rage was pointed outwards, not at himself. Unlike Clapton’s, his isn’t a rise and fall and rise again narrative. Rather, the last half-century has seen creativity on a sustained level, perhaps without the sky-kissing highs but certainly without the plummeting lows.

“Maybe because I’m not totally wedded to the music business,” he muses. “Don’t worry, I’m very serious about it, but I’ve got other things too. I think you’ve got to have a full life and not think you’re the most precious thing ever, otherwise you’re in big, big trouble.”

Is he still the fastest gun?

“No, [John] McLaughlin is,” he decides. “He’s ridiculous.”

People are still fascinated by all that, aren’t they?

“I’m not interested,” he says. “You can impress me once on a track and I’m totally yours. But then you listen to [jazz legend] Django Reinhardt and it’s all over. A lot of speed guitar players are illusionists – the distorted guitar doesn’t really allow the articulation to come through as clearly as it does with an acoustic guitar. Speed? I can do it, I just don’t choose to.”

If he was to survey the last fifty years, would he take anything of his own out to listen to for pleasure?

After a heavy sigh: “No. Because they’re all flawed. Even if somebody says: “Oh, let’s play that,” or a new band member goes: “Oh, play that,” I would have to go out of the room, because what I did then is not how I would do it now. So it’s like, woah, what a missed opportunity! Bad tuning, a rubbish drum sound that I somehow allowed…”

So should he be filed under ‘flawed genius’?

He laughs. “Flawed, maybe,” he says. “I don’t know about genius.”