Although it’s almost exactly 50 years ago, Doug Gray still recalls the day that his Marshall Tucker Band bandmate guitarist Toy Caldwell, introduced the group to a new composition called Can’t You See during a rehearsal in their home town of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

“Toy walked in and said: ‘I want you to hear this song I’ve been working on; I’ve got a great first verse,’” the singer relates nostalgically. “I had to write down the second verse on a piece of brown paper because Toy couldn’t remember it. I’ve still got that piece of paper, as a matter of fact.”

Caldwell’s first arrangement of it was fairly primitive, and after the band decided that what it really required was a flute intro they turned to their gifted multi-instrumentalist Jerry Eubanks. The flute isn’t used much in southern rock, but Eubanks’s swooping, summery solo, evocative of a summer skylark, became a signature element of the song.

“We knew that we did not want a run-of-the-mill guitar or a piano part, so to make it unique we called up our buddy Jerry and he came up with something that fitted,” Gray explains.

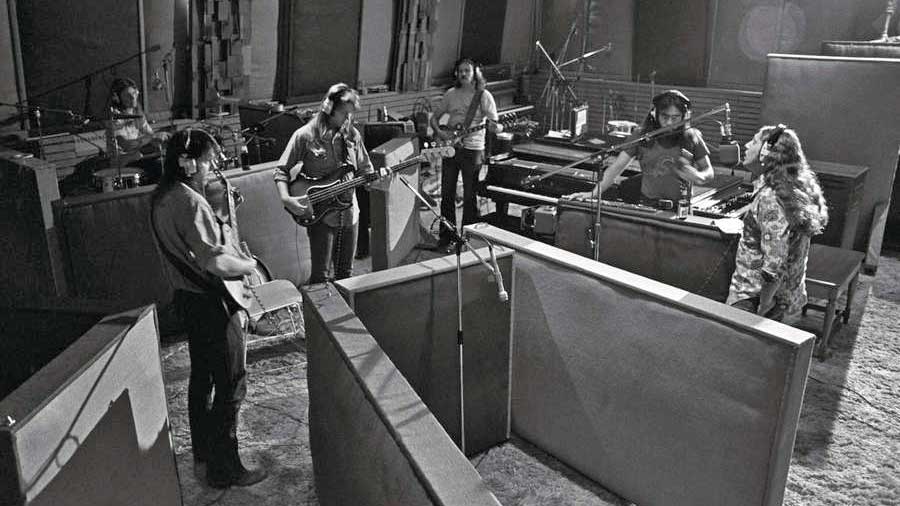

Although he could have got territorial, when the quintet arrived at Capricorn Sound Studios in Macon, Georgia to work with producer Paul Hornsby, Gray proposed the song’s composer, Caldwell, should sing the song instead of himself.

“It was better suited for a rougher voice than mine,” he reasons. “I knew right away that that song did not belong to me [as the singer], it was America’s song. It belonged to the universe.”

“I ran through it a couple of times and purposely sang like crap,” Gray laughs. “So we gave it back to Toy and he laid it down in ten minutes, far better than I could. He sang like he was testifying. Now that it’s become a universal song, I always ask the audience – which is comprised of folks from ten years of age to people older than me, and I’m 74 now – to sing the first verse. Now all of those folks testify too."

“Even yesterday I was singing that song up in North Carolina, and in Nevada the day before that, but we had no idea that the song would become so popular,” he continues. “Can’t You See has been heard in pubs and clubs and on stages right across the world.”

Coloured by lyrical references to riding a freight train, Can’t You See paints an evocative picture of the American South, although with its subject aiming to ‘find me a hole in the wall’ and ‘crawl inside and die’ there’s also darkness present. It’s certainly a song of contradictions.

“It truly is,” Gray agrees. “And we didn’t realise this until five years ago, that the titles of all our albums from the second one onwards have references that all correspond to each other [and escapism in general], from A New Life [’74] and Searching For A Rainbow [’75] right through to the most recent one we did [2007’s The Next Adventure]. That wasn’t intentional, it just happened that way.”

The Marshall Tucker Band’s self-titled debut album was a US Top 30 success, but when Can’t You See was released as a single it peaked at No.108. Later on, Capricorn gave it another try, but it barely grazed the Top 75. Although the song was never a massive hit when it came to sales, it has enjoyed longevity and renown.

“That’s true, and I don’t know why,” Gray says. It certainly helped that the band enjoyed a couple of bigger hits during the same decade, notably Fire On The Mountain and Heard It In A Love Song, which allowed them to grow.

“I could play you a version of Waylon Jennings singing Can’t You See [in 1976],” Gray enthuses. “The Zak Brown Band cut it with Kid Rock [2010]. It’s made us a considerable amount of friends, and that’s before we get into contestants covering it on TV singing shows like The Voice. It’s in five Netflix movies right now.”

The song was also covered by Black Stone Cherry and, er… Poison. Is Gray familiar with those? “Yuh,” he affirms. “I’ve got about forty versions of Can’t You See by other artists.”

With this year marking the 50th anniversary of the Marshall Tucker Band, Gray intends to continue gigging until the moment he drops.

“The original band was only together for eight years and I’m the last of those guys, but what makes me proudest is that we are still going strong,” he beams. “Most of the current guys have been with me for twenty-five years and it’s a solid band. It’s going to be that way until I wave goodbye from my gurney after I die on stage. I won’t be retiring. There’s still too much fun left in me."

Lynyrd Skynyrd are on their final lap, and the MTB’s friend and collaborator Charlie Daniels died in 2020. When Gray is asked if he fears for the future of southern rock, he sidesteps our question.

“The new way is the old way – that’s the way it should be,” he insists. “Blackberry Smoke are doing it right. They’re not hard rockers, they have meaningful songs and they’re creating new memories from what’s gone before.”

But when compared to the goliaths of the genre, why are the Marshall Tucker Band not better known?

“We never took advantage of a death,” he replies, leaving that remark to hang in the air for a moment. “So many other bands did it. People tried to make us do the same [Toy Caldwell died in 1993, a decade after leaving; his bass-playing brother Tom died in a traffic accident in 1980], but we just wouldn’t.”

Marshall Tucker visited the UK only once, with labelmates Grinderswitch and Bonnie Bramlett as part of a 1976 Capricorn Records package called Straight Southern Rock, but Gray has no regrets.

“I wouldn’t have done anything any differently,” he concludes, eyes twinkling. “I did my share of every drug you could find and any experience you could have wanted. When the southern bands went out together, I protected them.

“I had the ability to act straight to explain away a TV set exploding after a beer had been poured into it: ‘I don’t know what happened, sir… that thing just blew up!’ I knew that my brother Ronnie [Van Zant, of Skynyrd] had done it, but I lied like a motherfucker. Somebody had to!”