Ask anyone who saw King Crimson’s 27-date tour of the UK in November and December 1972 what they recall of the show there’s a good chance that the name of one person will be uppermost in their memories: Jamie Muir.

The death of the 82-year old musician and artist sparked numerous tributes and a wave of appreciation not just for his work as a member of the now-legendary Larks’ Tongues-era quintet but also for his pioneering contribution to the UK’s free jazz scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s where he worked as part of The Music Improvisation Company alongside luminaries such saxophonist Evan Parker and guitarist Derek Bailey.

Although Muir was only a member of King Crimson for a few months he was a hugely influential figure, not only during his tenure on stage and in the making of the Larks’ Tongues In Aspic album, but also left a legacy would resonate through successive line-ups thanks to his coining of the phrase ‘larks’ tongues in aspic’ when he was once asked to describe that quintet’s music.

Born in 1942 after initially taking to the stage as a trombonist after being expelled from art school in Edinburgh in 1966, he would ultimately become a drummer. Having founded a group called The Assassination Weapon in which he also controlled the band’s psychedelic light show, his aim shifted from Edinburgh to London where he quickly became embedded in the improvisation scene while funding himself with a day job as a salesman in Bentalls Department Store. Muir, who was also briefly a member of Pete Brown’s Battered Ornaments, saw King Crimson performing at Hyde Park in 1969 when the original group supported The Rolling Stones. Impressed by the force of Crimson’s set, decades later he told me in the first of many interviews, “Most bands come along and then develop but Crimson just came on and exploded with this very adult, intelligent, cutting-edge music. It was just this whole package that went wallop!”

Muir also played with Sunship, a jazz-rock outfit that included ex-Soft Machine sideman saxophonist Lyn Dobson, Allan Holdsworth, and future Gilgamesh/National Health keyboard player Alan Gowen, with whom Muir had also played in the Afro-rock combo Assegai in 1971. The other notable band Muir was part of was Boris. Championed by Melody Maker’s Richard Williams, Boris mixed rock, jazz, free-improv, and theatrical presentation led by Muir himself. Williams, who recommended Muir to Robert Fripp in the summer of 1972, recalls, “Jamie was such an interesting man. He was a funny combination of intensity and craziness. There was a looning side to him obviously. That Dadaist thing was interesting. He was obviously very serious but serious in a way that most musicians wouldn’t have understood, which is why Robert, even with his meticulous viewpoint, did respond to him.”

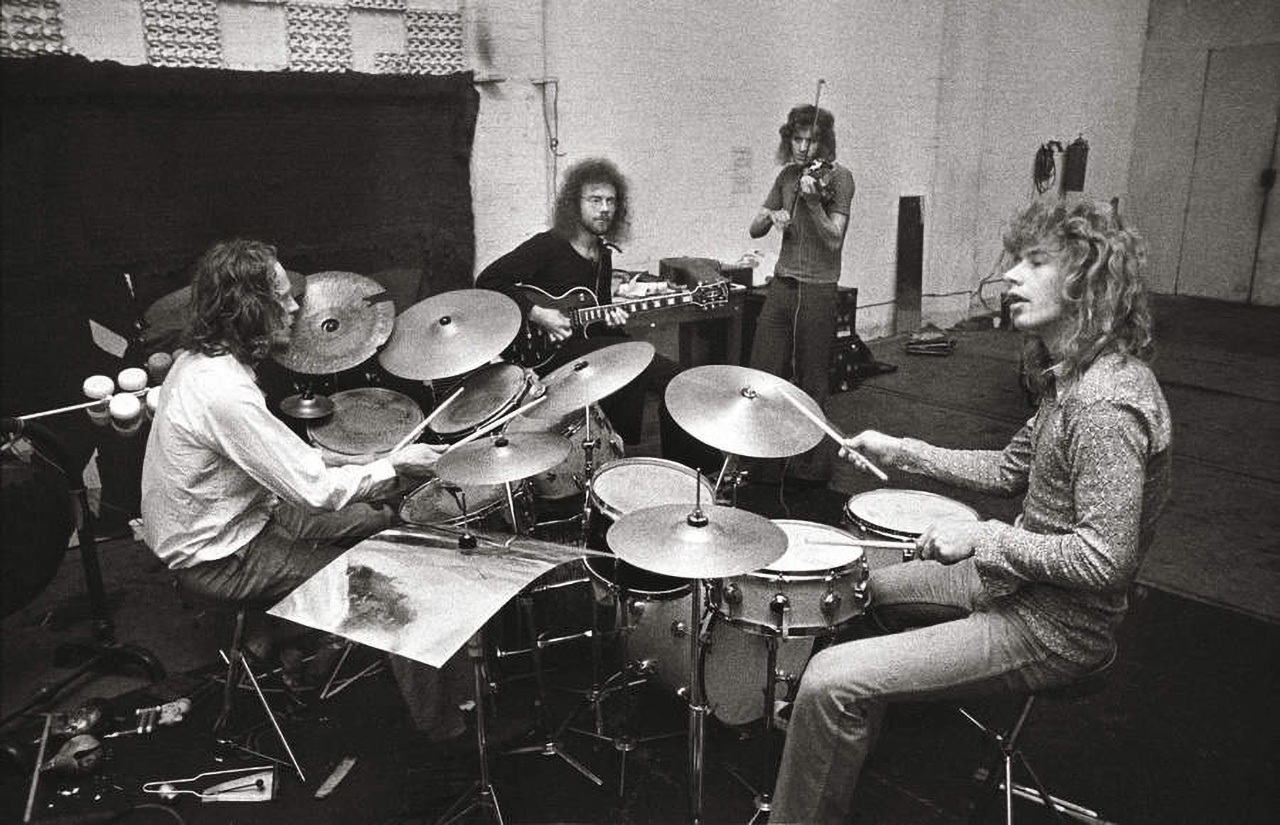

Just three years after witnessing King Crimson Muir found himself jamming with Robert Fripp to become the first recruitment to the new incarnation of King Crimson. Jamie recalled the occasion. “Fripp came round and we played for a couple of hours, upstairs in my little rehearsal room with mattresses plugged up against the windows. All I remember was playing some really fast and furious blowouts, which from a drummer’s perspective was the Tony Williams/Billy Cobham type of thing. It was fairly energetic stuff and I think we enjoyed ourselves. My feeling about getting the call was: ‘Terrific.’ King Crimson was the ideal for me because it was a rock band that had more than three brain cells. I was very much more an instrumental style of musician rather than being song-based and there weren’t many other bands that I would have been any good in. I was extremely pleased and I felt completely at home with Crimson."

A little older than everyone else, he was quick to lead with suggestions for ideas or approaches to the material and musical vocabulary they were attempting to develop. Such was the sense of adventure and open-mindedness in those formative days nobody in the group baulked at or questioned the percussionist’s arsenal of pistachio shells, bags of dried leaves, domestic baking trays, tuned plastic bleach bottles, old suitcases, rolled-up newspapers, a large saw, duck calls, toys, and an aerophone - a brass mouthpiece affixed to a length of rubber hose which when whirled above the head produced a pitch with a doppler effect - in addition to a more conventional drum kit, cymbals and gongs.

Situated near the centre of the stage, Muir provided a visual focus for many in those audiences. Dressed in a split fur jacket that had once belonged to a girlfriend, he resembled something akin to a shaman dressed in animal skins as he moved rapidly around his array of percussion and toys. In the climatic sections of the music, he would work himself into a frenzy, moving with an anarchic abandon as though possessed, flailing his kit and nearby equipment flight cases with chains while appearing to be spitting blood from his mouth. Although these were theatrical capsules secreted in his mouth, the visual effect was startling. If the punters regarded him as something of an eccentric performer, then spare a thought for his fellow musicians on stage who had no inkling as to what Muir would do when he joined them on stage.

Many of the sounds and ideas Muir came up with were adopted and accommodated no matter how unorthodox they appeared to be. During the making of Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Muir suggested the buzz of overlapping voices heard at the coda of LTIA Part I, the otherworldly and tape-manipulated sounds that grace the opening of Exiles and of course, recording the sound of hands sloshing around in buckets of mud during the introduction of Easy Money. While many of these sounds were fleeting and ephemeral in their nature and deployment, that did not prevent them from becoming etched into Crimson’s future musical vocabulary. The shocking screeching marking the transition between the climax of The Talking Drum and the grating intro of LTIA Pt II was produced by the band members blowing as hard as they could into the reeds of vintage bicycle horns. Many of those sounds left an indelible drummer Pat Mastelotto, whose habit of triggering electronic samples of Muir's work had the effect of summoning that mercurial spirit into the 21st-century body of King Crimson.

Prompted by a profound spiritual awakening, Muir quit Crimson, music, and London, after the recording of Larks' Tongues In Aspic in February 1973. However, before driving north he paused long enough to tell Yes’s Jon Anderson about Paramhansa Yogananda’s book, Autobiography Of A Yogi and thereby inadvertently inspired the conceptual framing for Yes’s Tales From Topographic Oceans. Thereafter Muir joined the Samye Ling Monastery near Eskdalemuir in southern Scotland to pursue a monastic Buddhist life, also attended by artist Fergus Hall who would provide the cover art for The Young Persons’ Guide To King Crimson and The Compact King Crimson. Upon returning to secular life in the early 1980s Muir once again became part of the improvised music scene and also took to painting large surrealist paintings. Not many of these have survived thanks to Jamie’s habit of burning those canvases he no longer liked. Happily, a less pyrotechnically inclined means of deleting unsatisfactory work presented itself after he began creating digital art in the early 2000s.

Although I only saw Jamie once in December 1972 with King Crimson, the memory of his incandescent presence never left me. I'm doubly lucky to have talked to him several times in subsequent years about that period of his life. Not only was he an inspiring, catalysing force of nature, he was also a lovely, modest soul. A long-time resident of Somerset, although he'd clearly moved on with his life, whenever I talked to him Jamie retained a great fondness for what was achieved during King Crimson. “The essence of it was that we were five musicians carrying with them their qualities and gifts and still trying to find a way of welding it all together into one distinct personality.”