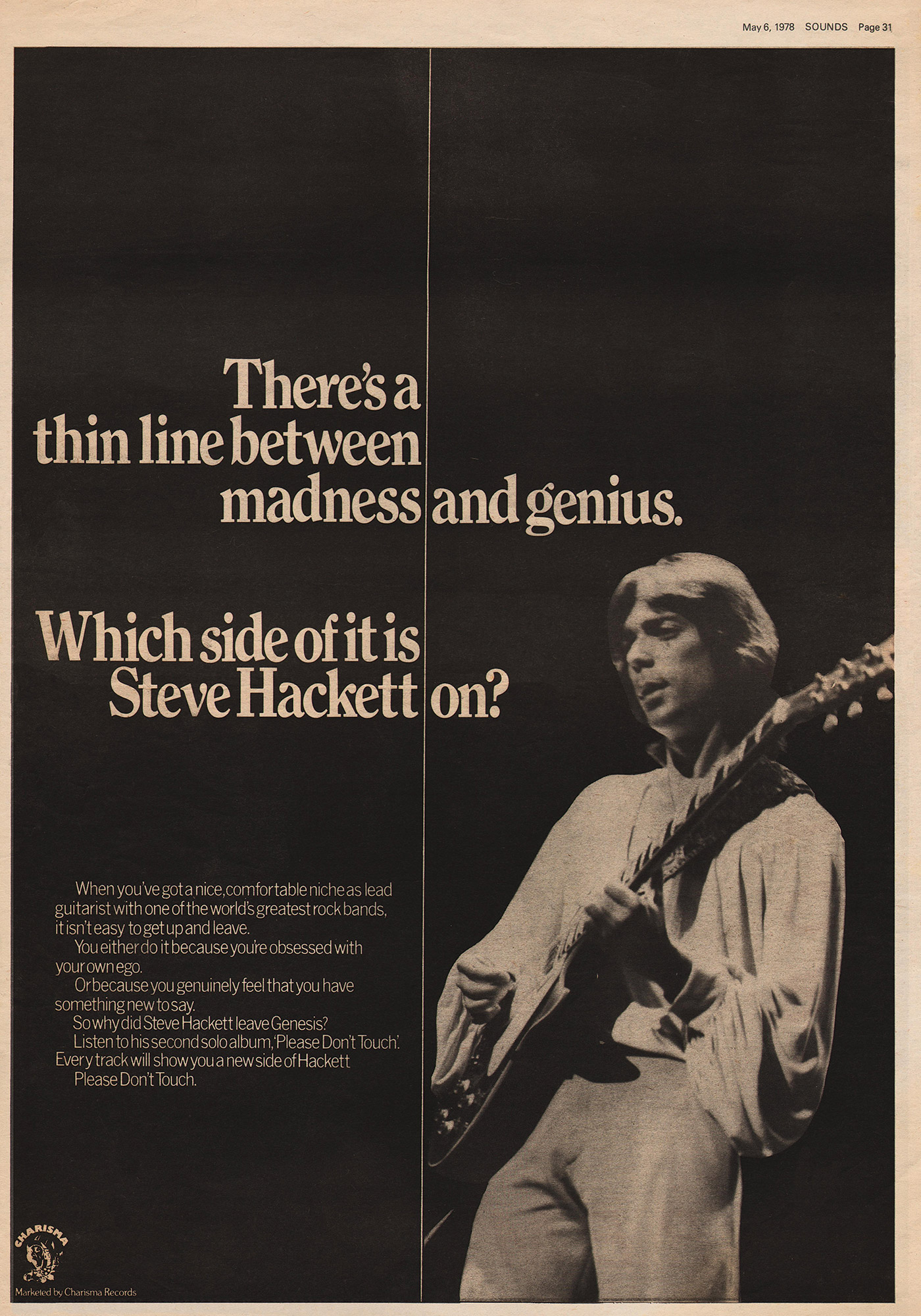

A press advert for Steve Hackett’s second solo album 1978’s Please Don't Touch, showed the recently ex-Genesis guitarist, eyes closed in concentration, fingers shaping a chord, beneath the headline: “There’s a thin line between madness and genius. Which side is Steve Hackett on?”

Nearly 40 years later, that question remains unanswered. But the Steve Hackett who arrives this morning at a rehearsal studio in Putney, south-west London, seems to be straddling the line rather well. Shy, polite and quietly witty, this 67-year-old possible ‘mad genius’ has hidden depths: a man with a deep interest in spiritual matters who claims to have healing powers – or “Nurofen hands” as he jokingly calls them. But more on that later…

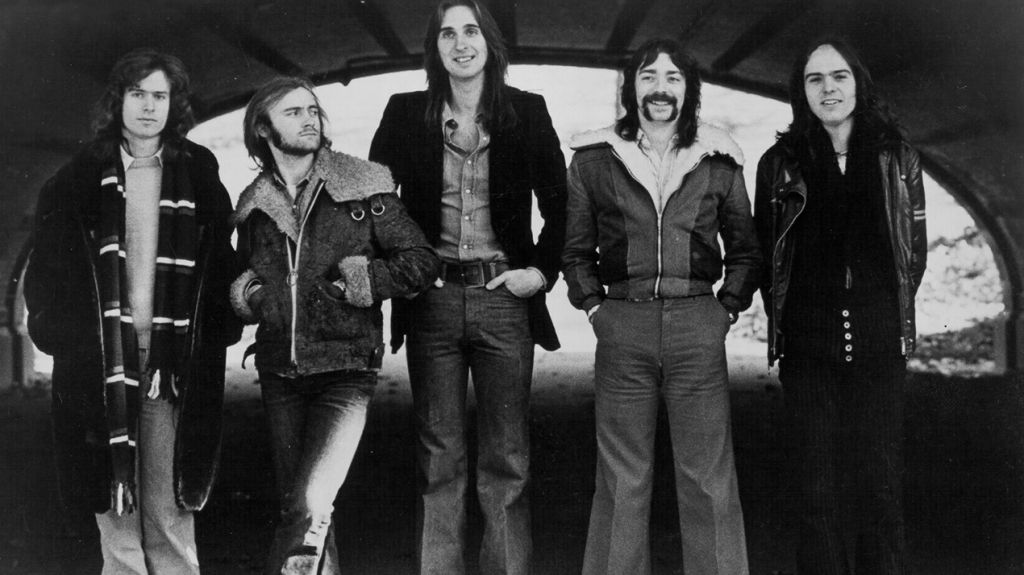

Stephen Richard Hackett was born to play music. He could blow a tune on the harmonica by the time he was four, and was in several aspiring pop groups (Canterbury Glass, anyone?) before joining Genesis in late 1970. Hackett’s fleet-fingered solos and melancholy tone helped define the likes of Dancing With The Moonlit Knight, Firth Of Fifth, Carpet Crawlers and Entangled. Then he left to go solo, flitting between mind-scrambling prog rock, acoustic and Latin music, and more recently exploring his old group’s back catalogue with the Genesis Revisited albums and tours.

Hackett has experienced commercially challenging times. But 2012’s Genesis Revisited II proved a welcome boost which has carried over to his subsequent solo career. His latest work, The Night Siren, is a call for peace and unity in troubled times, and a whistle-stop musical tour of the globe, from Iceland to Peru via the Middle East and more. “I think of myself as a bumbler,” Hackett says, settling down in his chair with a wary smile and a mug of tea. “But occasionally I have insights and bumble no more…”

This new album, The Night Siren, is ‘world music’ in the real sense of the word.

Yes. For me, though, it’s the natural consequence of having visited a whole ton of places. The idea of a musical fellowship thrills me. I love working with people from Iceland, Peru, Hungary, Azerbaijan, the USA, the UK, Israel, Palestine… The second song, Martian Sea, has something which sounds like a sitar, and by the end of it there’s an Arabian oud and flutes going on. That one was a deliberate attempt to get some free-range 60s sounds on the album.

You grew up near London’s Kings Road in the 60s: surely this was the perfect place for a young musician?

We lived on a housing estate in Pimlico, but near Chelsea, so there were exotic things happening on the doorstep. From the age of 12 I’d look at what was around and often passed the odd Rolling Stone in the street. I became fascinated by music at a time when every other track on Radio Luxembourg seemed like a masterpiece. You don’t know what you got, till it’s gone – to quote Joni Mitchell. We thought the 60s would go on forever.

Your first group, Quiet World, came from that scene in 1970.

Yes, by which time the music had changed again and you had formally trained musicians working with the hippies, and something extraordinary was born out of that. I’m happy to name those who were a big influence on me personally and Genesis: Procol Harum, Jethro Tull, King Crimson, Yes. Those bands were all like separate research facilities.

How did you support yourself around this time?

A mate worked at the Labour Exchange and offered to put me on the dole. But I didn’t want to feel like a sponger. So I had five years of ordinary jobs after leaving school. One of them was a temp job with a surveyor where my responsibilities began and ended with banging nails into the pavement around Victoria Street. Some of my nails are still there. I liked it because I could switch my mind off and think about music.

Your first Genesis concert was at London’s City University in 1971. Apparently, Phil Collins was so drunk he kept missing the drums. Were you aware of this?

I’d never done a Genesis gig before so I didn’t have anything to compare it to. I thought, “Perhaps the drummer always plays like that [laughs].” But I was busy trying to control my guitar feedback – and failing. I remember the rest of the band not being at all happy at the end of the show, and me thinking it was all my fault.

Mike Rutherford described you at the time like so: “Black corduroy jacket, black jeans, black shirt, black hair and moustache… Steve was all black.”

I still am! [Looks down, laughing at his black jeans, trainers and fleece.] Still dressed in black.

Were you very shy then?

Yes, I was. But it was a funny thing being thrown into a world of people who all seemed to speak Chinese. I didn’t understand a word they said.

Mike Rutherford’s a bit of a mumbler, though, isn’t he?

Yes [begins perfect Rutherford impression]: “Talks very quickly like this, public school, father’s military background… blah, blah… What do you think Steve?” “Er, I’m sorry, I didn’t hear a word of that” – and I’m still munching on this biscuit. We came from different backgrounds.

Was it a happy time?

I look back on it with great affection. My rite of passage coincided with the rise of a band becoming world famous, quite by chance, I think. But we applied ourselves to it almost like being in the civil service. There was this aspect of Mike, Peter [Gabriel’s] and Tony [Banks’] formal education [at Charterhouse school] which permeated everything. For instance, I couldn’t understand why rehearsals ended at six o’clock, and everybody downed tools and went home. But that’s how it was with Genesis.

You also sat down on stage for the first few years. What was with the stools?

I was told when I joined that we all sat down on stage, apart from Pete. Pete was the show and we were like the pit orchestra. We stayed seated until Phil took over, and Mike said [starts mumbling], “Right, Phil’s singing, we don’t know how this is going to go, we should all stand up…” That’s when I thought, “I better get some stage clothes and shave this moustache.” We suddenly became a different band.

You once described Genesis as “repressed English guys”. How much did that repression and Englishness influence the music?

That’s where the storytelling comes from. If you take guys who are removed from the world of women completely for a while, most of the romance they experience is not going to be on a Rolling Stones level. It’s going to be on the level of, “I am reading Greek mythology and this particular goddess said this…” That’s why the world of literature permeated early Genesis’ work.

There are also literary references in your solo work. The title of the 1984 album Till We Have Faces and the 1978 song Narnia both came from CS Lewis. What are you reading right now?

I’ve just finished Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts, about an Australian drug addict, who breaks out of a brutal jail and makes his way to India. He ends up living in a shanty town, where he starts an unofficial clinic. So, on one level, he’s doing this almost saintly work and on another he’s involved in organised crime. It’s poetic and violent and a wonderful contemporary account of India.

Shantaram seems to tap into The Night Siren’s global theme. The first song on the album, Behind The Smoke, addresses the refugee crisis, and some of your ancestors were refugees.

My ancestors escaped pogroms in Poland in the late 1800s. They travelled in fear of their lives to Portugal, and some later made their way to England, changed their name to Davis and survived in the Jewish East End of London. I had an uncle, Jack Davis, who was the oldest serving soldier in the First World War. He lived to be 108. I met him in the last year of his life and he greeted me with, “Congratulations on your success.” What an extraordinary thing for a 108-year-old man to say. I replied, “Congratulations on your success.”

Your first solo album, Voyage Of The Acolyte, was inspired by the tarot. Are you a believer?

I believe in the spirit world. I’ve had experiences. It goes back to childhood where I discovered I could see soundwaves. I remember gripping my mother’s hand, thinking they were going to kill me.

What does a soundwave look like, then?

They were these lines in the air [holds out his hand], going ‘phutt, phutt’ – like electrical charges. But they stopped just before they reached me. I stopped seeing them when I became an adult.

When did you became interested in the spirit world?

When I was in Quiet World, the Heather brothers [Hackett’s bandmates, John, Lee and Neil] had a father who was a medium. I used to visit the spiritualists at 33 Belgrave Square, the building [Sherlock Holmes author and spiritualist] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave to them. You usually saw these little old ladies who’d give you a reading. I went once because I had a pain in my toe. They said, “We’ll ask our brothers and sisters in the spirit world to help you,” and I walked out of this place and the pain had gone. Then I discovered that in a small way I could do healing for other people.

How did you find this out?

I was 25 and in a medium circle where would-be mediums practised on each other. One of them said she could see a blue light in my stomach, which, apparently, shows an ability to heal. I’m not infallible, I’m not professional, I don’t take money. But it’s something I do.

So, if I said I was in pain, could you heal me?

I might be able to help, but I can’t fix anything life threatening. It’s not, “Take up your bed and walk.” But if someone has a headache or a backache and asks me to help, my hands kick in like a battery – boom! I experience a feeling like pins and needles. I think of it as an alternative to a pill. My hands can “do Nurofen” [laughs].

You once described your solo career as “a gigantic experiment and a big hit every 10 years”. Defector, Cured and Highly Strung were all Top 20 albums in the 80s. Were you under pressure then to sell more records?

The 80s brought certain pressures to many acts. I remember Eric Clapton saying, “Every year the knife cuts deeper,” as he was being edited by the people at his record company. I did have a hit single with Cell 151 [Number 66 in 1983]. Charisma Records wanted a hit single from me so we did everything necessary to achieve that.

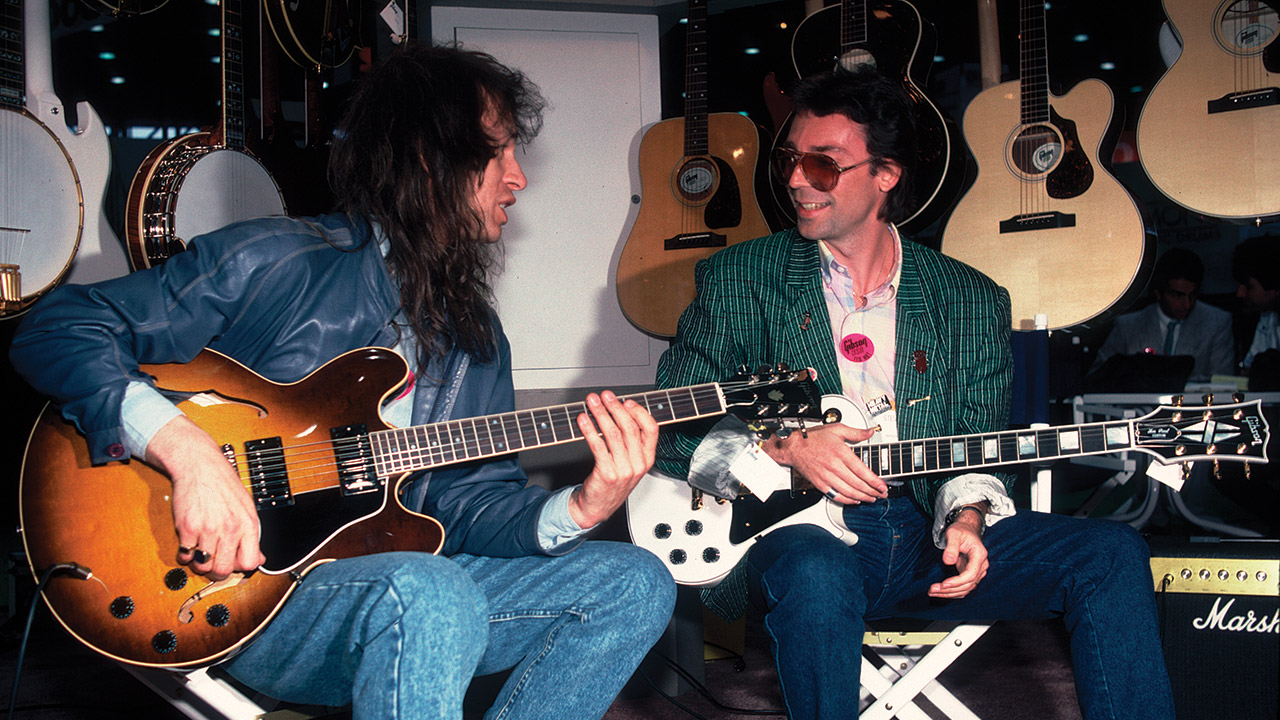

Did that same mindset influence GTR, the group you formed with Steve Howe in the mid-80s?

Steve and I felt we could bridge the gap between Genesis and Yes, do something our fans would think was valuable, but at the same time reach a new audience. But Geffen Records, who were going to sign us, didn’t want new guys in the band with Steve and I.

They wanted another Asia?

Yes. They wanted another Asia [laughs]. But we weren’t prepared to sack the other guys. We signed to Arista who wanted a – quote – “hit rock band”. I still think [the single] When The Heart Rules The Mind sounded great on American radio. We had a hit, but it wasn’t sustainable. [GTR and ex-Yes manager] Brian Lane likes to divide and conquer, so he set everyone at loggerheads with each other. I should have seen it coming. Politics ruined that band.

Did that put you off being in a band again?

Well, with a solo thing, there’s no agenda. I just want the best out of everyone. As a bandleader I am quite benign…

A benign dictator?

I can if I need to be. But everyone naturally does what I’d like them to do. Everyone in this group is free to insult everyone else equally [laughs].

Having a lead singer like Nad Sylvan must make performing Genesis material much easier. He has a ‘Genesis voice’ and he looks like a frontman with that hair.

The hair alone! Nad can ‘do’ Genesis. But he’s probably more in the style of early Peter Gabriel – very theatrical: “Here I am dressed as Britannia, and I’m going to hold the position long enough for photographers to get the shots.” That’s something Nad has. He turned professional from doing this. As he’s said himself, he’s in his 50s, so it has happened rather late. But he still looks like a kid, like a Nordic bronzed god [laughs].

People like me who discovered Genesis through Seconds Out have a real soft spot for the four-piece line-up. Do you think that era is overlooked?

Yes. Chris Squire always said his favourite Genesis album was A Trick Of The Tail. But in conversation people tend to say there was “The Pete Era” and “The Phil Era”. They sometimes forget what came in between. I think the band was cusping at that time. The material was accessible, there were still these instrumental extravaganzas like Wot Gorilla and Unquiet Slumbers For The Sleeping – with aspects of jazz, classical and Latin music.

You’re promoting The Night Siren but also celebrating 40 years of Wind & Wuthering on your tour.

It feels wonderful to be celebrating Wind & Wuthering. But I have resisted the idea of doing an entire album. I prefer to cherry-pick and not play the, er, weaker tracks, if I can use that expression. Sacrilege! But there are certain tracks we ditched.

What are you playing from the album?

Eleventh Earl Of Mar, One For The Vine, Blood On The Rooftops, Afterglow, …In That Quiet Earth… and Inside And Out [from 1977’s Spot The Pigeon EP], which should have gone on the album. It’s a very good tune and this band does a really good version. I say that proudly, because I wondered if we could pull it off. But the spirit of the song is intact.

On the Genesis Revisited tour in 2014, you used to joke with the audience that “The museum is open.” Do you still feel like its curator?

Yes, it’s a bit like I’m keeping the museum doors open. The exhibits have been dusted off and they still shine.

Did you get any feedback from the rest of the band about Genesis Revisited?

There is a band policy not to comment publicly. Privately, but not publicly. Because it’s a very competitive setup, I don’t expect any of them to ever come to my shows. Because that could be perceived as sanctioning them, and that would be wrong. That’s the unwritten Genesis rule. Whereas personally I have seen shows of Phil’s, Pete’s and Mike’s and would go and see Tony’s, if he did one.

Which did you enjoy the most?

[Long pause] I enjoyed Pete’s the most, especially the stuff he did around the time of his third and fourth albums. He and I spent a bit of time together during that period. I thought with that third album, he’d developed a style of his own. Pete said he’d taken a radical step in what seemed like a less romantic direction. I think the subsequent album was perhaps more… ethnic.

Most of your album, Till We Have Faces, was recorded in Brazil at that same time.

Yes. I became immersed in the world of Brazilian percussion. I played the album to Pete and he said, “Can you give me some phone numbers? I’m going to Brazil.” People say Pete is “Mister Ethnic”, but I played thumb piano, [zither-like string instrument] psaltery and [South American percussion instrument] rainstick with Genesis, though it wasn’t credited. What links Pete’s approach and mine is that we both try and work with people from different backgrounds.

Presumably you’ve read Phil Collins and Mike Rutherford’s autobiographies. Do you think they fairly represented your role in Genesis?

I’ve read them both. Let’s put it this way: my function in Genesis was completely different to how they perceived my function to be. I will tell what that is when I complete my book. I have started writing it but I am very busy, so it will take a while.

When you walked into the room for that meeting with Gabriel, Banks, Collins and Rutherford in 2005, how confident were you of a five-piece reunion?

I was told to arrive at a certain time, but the meeting had already convened, and by the time I arrived they had already fallen out [sighs]. The idea was for the five of us to do some shows around the anniversary of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway and a possible musical. Tony didn’t want to do the musical… But the agenda was set before I arrived.

As the keeper of the old Genesis flame, what archival releases would you like released?

Personally, I hope the bootlegs are officially sanctioned. On the bootlegs from The Lamb…, you can hear us going to town on all these atonal things, and that was largely my influence. Put them out! But I don’t control the purse strings.

What happens after this album and tour? Or do you not plan that far ahead?

There are a ton of dates planned for this year, and new territories opening up, which makes it hard to think any further. You know, for a long time I had to work very hard to get people’s attention. That’s changed. I never wanted pupils or disciples, but now people want to know me and ask me “How did you do that?” I find it all highly amusing, but it’s good. I guess I must be doing something right.

This article originally appeared in issue 76 of Prog Magazine.