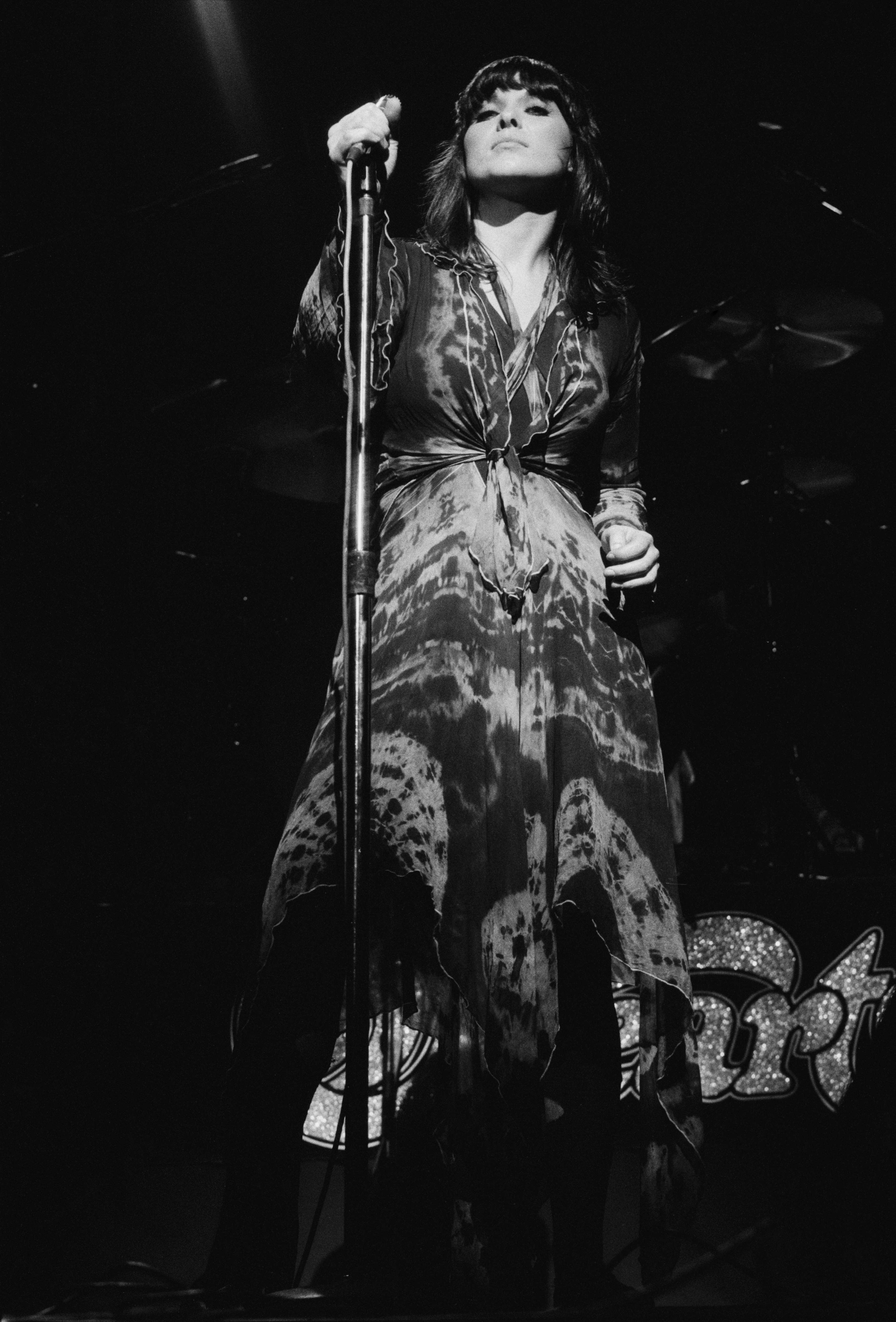

When AOR chief of operations Geoff Barton asked me to write about Heart, I thought Christmas had come early. Y’see, me and Heart go back a long way. We first met in late 1976, although they won’t remember it. I was in the audience at the New Victoria Theatre in London and they were on stage, playing their debut UK gig. Ann and Nancy were dolled up in cool 70s hippy chic, knocking out spellbinding music fashioned from bruising heavy rock and jangly folk.

Early Heart were great, no question. They cranked out a handful of super-fit albums during the 70s, kitted out with brilliant Zeppelin-inspired rock, before morphing into one of the world’s greatest AOR bands during the 80s. The following decade was less kind, but they’ve revived their activities in recent years, with albums like 2004’s Jupiters Darling, 2010’s Red Velvet Car and last year’s Fanatic.

It’s good to know that some things just keep getting better as time moves on, and the latest version of Heart is no exception. Fanatic showcased a startling mash-up of crushing rock and a trippy, acid-embellished softer side. Nancy’s guitar tone now sounds like Billy Gibbons stopped by and plugged her into his blues rig, while Ann is taking on an altogether otherworldly vibe. A remarkable feat considering that these two ladies could have packed it up years ago for a life in exile on some private island in the south pacific. The sisters feel hugely energised by this turn of events, planning to keep the ship afloat as long as the spark of creativity burns bright.

If they had ‘retired’ for good, few could have blamed them. Heart have enjoyed tremendous commercial success but it has come at a price. If you think that beneath all those glossy, happy-go-lucky smiles there wasn’t drama or turmoil, well, think again. Sure, we’ve been privy to the trials and tribulations of crazy combos like Guns N’ Roses, Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, but the real surprise is the amount of subterfuge and skulduggery that appears to have infested the genteel world of Heart. (Coincidentally, Heart rejoiced under the tag ‘little Led Zeppelin’ at the start of the career.)

Theirs is not only a story of success over adversity, but one of struggle, strife and romantic acrimony involving former band members, record labels and self-confessed drug indulgence. It’s been a never-ending stream of ups and downs, strikes and gutters, but Heart have managed to re-emerge from this tumult feeling a whole lot brighter.

“I think that the 80s were a great lesson for us,” says Ann, via transatlantic telephone link. “That you can have huge success, hit records and money but you can also really lose your way and let slip the very thing that’s really keeping you interested and making you happy. It’s one of those lessons of life that you have to learn to stay on track.”

While Heart’s mid-80s MTV success took them to great commercial heights, it was during the 1970s that the band enjoyed their most joyous times – as well as tolerating their most maddening moments. They started out as a folk-rock band, signed to a small independent label, Mushroom, that would ultimately entangle them in a hugely draining and largely unnecessary lawsuit. Their well-documented intra-band romantic relationships made Rumours-era Fleetwood Mac seem all sweetness and light. They were, in effect, riding a runaway career that would eventually nose dive – a predicament that led to a two-album career-stalling period in the early 80s.

It was only with the emergence of MTV, and the realisation that – with their mountainous hair, tight corsets and glamorous make-up – Ann and Nancy were an easy sell to the fledgling network, that Heart began to pump out hits again. That period of the group is an entire story of its own, but let us focus, instead, upon the very beginning…

The Wilson sisters were born in California, vocalist Ann on June 19, 1950 in San Diego, guitarist Nancy on March 16, 1954 in San Francisco (a third, lesser known sister Lynn, four years Ann’s senior, would contribute vocals to Heart albums Little Queen, Private Audition and 1985’s Heart). Theirs was a military family, with their father John seeing active service in the South Pacific and Korea and eventually reaching the rank of Major. Posted as far away as Taiwan, in the South China Sea, John eventually settled with his wife Lois and their daughters in Bellevue, Seattle.

Taking a deep interest in all things creative, it didn’t take long for the sisters to develop a passion for music, a fascination fuelled by the The Beatles’ epochal appearance on TV’s The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. Like most Americans, the Wilson girls lost their mind to the sound of the Liverpool moptops pealing out She Loves You, a moment that shaped their lives forever.

Ann and Nancy soon immersed themselves in music, collecting their favourite records, idolising The Beatles and learning how to play instruments and sing. They formed an embryonic band, which they named Daybreak, performing at school, in churches and at friends’ houses.

Word of mouth led to a liaison with a country singer who needed a backing band to cut some tracks at a local studio. Daybreak helped out and were given the opportunity to record one of their own songs at the end of the session. Through Eyes And Glass was a fine slice of period sunshine pop and was released on Topaz Records, the studio’s own vanity label, in 1969, as a B-side to one of the country tracks.

Fuelled by the excitement of recording in a real studio and having a song of theirs released on a vinyl single, Ann in particular decided to get serious about making a career in music, working her way through a number of semi-professional band line-ups, before eventually hooking up with a unit called White Heart (a name that was quickly changed to Hocus Pocus) and featuring bassist Steve Fossen and guitarist Roger Fisher.

Unknown to Ann at the time, this liaison would soon lead to a pivotal moment in her life.

The year was 1971, and Hocus Pocus were playing as many gigs as they could find. It was a hard life, scraping around playing thankless shows and trying to live off what little money they earned. But like every fledgling band, they held on to a dream that success would be just around the corner. For Ann, there was an additional frisson of excitement in addition to the thrill of playing shows, as she soon became smitten with her guitarist Roger ’s brother, Michael Fisher. Fisher became her lover, her muse and perhaps, most importantly, the band’s de facto manager and soundman.

All, however, was not smooth sailing. The Vietnam War was raging, and compulsory draft was in operation in the United States. Like many potential conscripts, Michael was a conscientious objector, who did not want to play a part in the conflict. With no other way to escape being drafted and sent to fight in Vietnam, Michael fled to Canada, settling in Vancouver. Ann soon followed, as did the band, who relocated to Canada, where they shortened their original moniker, from White Heart to Heart.

Nancy moved to Canada in 1974, after graduating college, at the encouragement of Ann, who invited her sister to join the band. Reunited, the pair figured it was time to make another serious attempt at rock’n’roll stardom. Heart began playing anywhere and everywhere that would have them, in a final attempt to get the band off the ground.

It was around this time that they developed a penchant for covering Led Zeppelin songs with uncanny accuracy, Ann’s vocals ably evoking Robert Plant’s banshee wail. Indeed, Zeppelin once walked into one of Heart’s club gigs in Vancouver, after performing a show of their own, while the Wilsons were in the middle of covering Stairway To Heaven.

Weary from a never-ending stream of toilet-bowl gigs, most of which paid barely enough gas money to get their truck to and from the show, Heart found temporary redemption in the form of a local Vancouver studio called Aragon.

Built in the 1940s, Aragon was Canada’s first professional studio, recording mainly classical and swing music, until the Beatles appeared and the industry changed. The original owner despised pop music and in 1970 sold the business as a going concern to Jack Herschorn, who changed its name to Can Base, and then, later, the hipper handle of Mushroom. Herschorn also incorporated a fledgling production label. The first project under this arrangement was the recording and release of a now rare psychedelic album by a band called Christian, featuring future Heart guitarist Howard Leese.

Mushroom/Can Base studio was manned by Los Angeles-born record producer Mike Flicker and his engineer, the aforementioned Howard Leese (also from Los Angeles and also a one-time member of psych band The Zoo), and their plan was to sign and develop new acts. Mike Fisher got wind of the situation and approached the studio about Heart. They liked what they heard; however, Mushroom was only interested in signing vocalist Ann.

Ann insisted that they work with the whole group or not at all, so Mushroom decided to pass. However, a year later the label again approached the band with a fresh offer, a two-album contract to be recorded at Mushroom by in-house producer Mike Flicker. It wasn’t a great deal, but at least it was a step forward.

The band quickly recorded a series of tracks including the mystical How Deep It Goes, along with the epic Crazy On You, the powerful Magic Man, the dreamy Soul Of The Sea, and Dreamboat Annie, which would later become the centrepiece of the group’s 1976 debut album of the same name.

“That song was originally like a Beach Boys thing, a California Girls-type vibe,” notes Ann. “It wasn’t supposed to be in reference to me – it was just a random name, because it fitted the groove. The lyric then started to lead the song and it became about a little independent wooden ship, which developed into Dreamboat Annie.”

Flicker’s production worked wonders, while the musically gifted Leese helped to arrange the songs perfectly. It was, as they say, a match made in heaven. As a tentative first step Mushroom issued the single Crazy On You, in 1976. The single began to light up the switchboards at Canadian radio stations, signalling that Heart had finally arrived and – it must be said – in some considerable style.

The debut album Dreamboat Annie, released in early 1976, was well received by fans and critics. It mixed folk music with scorching hard rock much in the same style that Led Zeppelin had pioneered a few years earlier. It possessed a deeply satisfying sound, and showcased Ann’s incredible vocal range, set against songs that have now stood the test of time.

Heart’s drum seat was still technically vacant, so several percussionists were utilised on the recordings, including future Trooper man Duris Maxwell, and local boy Mike Derosier who would, later, assume a permanent position with the group.

Dreamboat Annie went on to sell over a million copies, but it was soon clear that Mushroom were underfunded to handle such good fortune, a small, boutique label that was now forced to play in the big league, with no staff and no clout. It was left to Mushroom’s promotion/marketing man Shelley Siegel to single-handedly bust chops on the band’s behalf; he even went as far as to relocate to Los Angeles, arranging for the album to be released on Capitol Records, where it quickly became a massive seller in the US market.

Despite the band’s reservations over Mushroom’s ability to provide bang for their buck, Heart continued to push forward, building up a solid reputation as a great live act, fronted by two attractive and highly talented musicians.

However, Mushroom published a tasteless advertisement featuring the Wilson sisters in the weekly trade bible Billboard. The ad was designed to imitate the front cover of US supermarket tabloid the National Enquirer, depicting the duo in a seductive, bare-shouldered shot with the subhead: ‘Heart’s Wilson sisters confess: It was only our first time’, implying that they were lovers.

The implication was further underlined by a radio promotion doofus in Detroit who rather churlishly asked Ann where her lover was, alluding not to her boyfriend Michael, but to Nancy. Ann was so incensed that she went back to her hotel room and immediately set to work on writing what would become one of Heart’s greatest tracks, Barracuda.

Matters within the group become even more complex when Nancy and guitarist Roger Fisher began a romantic relationship, one that would last for several years. This, in addition to Ann and Michael Fisher’s long-standing romance, made for complicated dynamics within the group, a situation similar to the emotional rollercoaster experienced by Fleetwood Mac at almost exactly the same time.

With momentum building faster than they could’ve reasonably hoped for, it was decided that, due to an obvious conflict of interest, Mike Fisher should step down as band manager and hand over the reins to Seattle-based Ken Kinnear. Kinnear’s first mission was to renegotiate the deal with Mushroom. The original contract called for just two albums but the royalty rate was lower than that enjoyed by successful acts. Mushroom foolishly refused to budge, and matters were further complicated by the fact Mike Flicker and Howard Leese’s decision to resign from Mushroom, leaving the label unable to fulfil certain contractual obligations. It was a tense time, and that tension would be ratcheted up to breaking point over the next few months.

In the meantime, the band had already started work on their follow-up album Magazine, recording basic tracks for five songs with Flicker at the helm. Work was halted when the band filed a lawsuit demanding to be released from their contract. Mushroom and Shelley Segal then set in motion what could’ve been a catastrophic manoeuvre by finishing and releasing the record as it stood. The raw, partially mixed tracks were augmented with ad-hoc live material together with Here Song, the B-side of their first Canadian single.

Bizarrely, the album even came with a disclaimer written by Mushroom on the rear of the album, reading “Mushroom Records regrets that a contractual dispute has made it necessary to complete this record without the co-operation or endorsement of the group Heart, who have expressly disclaimed artistic involvement in completing this record. We did not feel that a contractual dispute should prevent the public from hearing and enjoying these incredible tunes and recordings.”

This was an incredibly dumb move on Mushroom’s part. With several thousand copies distributed into the market, the band quickly secured a cease-and- desist notice, halting its sale. The gloves were well and truly off. The dispute became the hottest industry topic of the year, arguably only eclipsed by the ceaseless legal machinations of Boston’s serial court attendee Tom Scholz.

Mike Fisher, still involved with the band’s day-to-day activities, had managed to reconcile his draft-dogging status by paying a fine and thus avoiding a prison term, and was thus now able to enter America with the band. Heart began to play shows in the US, earning significant income that finally lifted them out of poverty. In addition, Ken Kinnear had negotiated a new worldwide record deal with the recently launched Portrait label, a powerful subsidiary of CBS Records. This eventually provided the band with a platform to release their third album, _Little _Queen, issued in May 1977 just one month after Mushroom had rush-released their version of Magazine.

A settlement was eventually reached with Mushroom. The court decided that the original contract should be honoured, but that Heart must be allowed to take creative control of the product and finish the record in a manner with which they were reasonably happy. Consequently, under watch of armed security guards on hand to prevent any sabotage the tapes on Heart’s part, the band relocated to Sea-West Studios in Seattle, where they overdubbed and remixed the tracks to their satisfaction.

Re-released in April 1978, exactly one year after the original incomplete version, Magazine was a hit, propelled by the success of the powerful hard rock track Heartless, achieving Platinum status and infiltrating the top twenty of the album chart.

Shortly after the album was released, Mushroom main-man Shelley Segal died, aged just 32, of a brain aneurysm. Both Wilson sisters attended the funeral. Later, in 1980, Mushroom declared bankruptcy, having failed to find another group to match the selling potential of Heart. The studio was sold but continued to operate, recording such local hard rock heroes as Loverboy and Queensrÿche. It’s still in business to this day.

When Little Queen was released, it was initially feared that the album’s sales would be diffused by the competing Magazine. However, Little Queen immediately smashed into the Top 10 of the Billboard album chart, going on to sell triple platinum. Little Queen was not just a commercial success, it was also a record of significant artistic accomplishment; many Heart fans consider it their best work. Lead track and first single, Barracuda, set the scene, with its galloping pace, supercharged guitar riff and Ann’s vocals reaching for the stars (and beyond).

The production, by Mike Flicker (with Howard Leese as additional guitarist/keyboard player), showcased the band in magnificent style, mashing exquisite folk elements with searing hard rock riffs. Tracks like Love Alive, Kick It Out and the caustic title cut positioned the band as major contenders, Ann and Nancy taking centre stage both musically and visually. Indeed, the allure of the two Wilson sisters became something of a hot potato with the rest of the band, as it was becoming increasingly clear that the world was viewing Heart as more of a duo, with a backing band.

“As much as we can, we’ve always tried to be democratic,” says Nancy, “even though we’ve come to learn through the years that Ann and I were the leaders, something that we had to accept. We got the most attention from the media; we were the ‘front-people’ and therefore we were the ones that the media wanted to talk to, interview and photograph. So we’ve had to patch up some bruised egos over the years. Ann and I were the ones that created the character and signature look of the band, so they all had to deal with their own ego trips and resentment.

“In my case I had two former boyfriends in the band, which was not the smartest thing to do,” Nancy adds. “In hindsight, what was I thinking? We were in a capsule moving so fast that the band was our sort of portable community. I didn’t have a chance to meet people outside of the band, so over those years we did a very Fleetwood Mac-ish type of thing internally, which certainly didn’t help.”

1978’s Dog & Butterfly album was another impeccable statement. Recorded at Seattle’s Sea-West Studios, the record was divided into two distinct sides: the hard-rocking and the contrastingly folksy Butterfly. Again, the album was a massive commercial success, selling a million copies in the first month, yielding two hit singles, Straight On and the title track, together with a brace of seriously impressive album cuts such as Cook With Fire, High Time and the brilliant Mistral Wind, which remains one of their most revered songs. From the exterior, it appeared that Heart could do no wrong. Internally, however, cracks were beginning to appear.

Similar to Fleetwood Mac’s romantic experiences, the relationships within the band had begun to fracture. Roger Fisher had been fooling around behind Nancy’s back, and the bond between them had weakened to the point where matters were becoming irreconcilable. She fell for drummer Mike Derosier, telling Roger Fisher that their relationship was over. Not unsurprisingly, Roger’s relationship with the group deteriorated, leaving them little choice but to fire him. As a founding member of the band it was particularly difficult decision, but necessary in order for Heart to carry on.

“When we split up originally, Roger was a little out of control with substances and he was not playing as good anymore,” reveals Nancy. “He’s was kind of in orbit and hard to reach. And then there was the attitude of the drummer and everything between those two guys, so there was really quite a bit of trouble at the end of that particular line-up.”

With two accomplished guitarists in the band already, the group didn’t feel it necessary to replace the departing Roger Fisher, especially as Nancy was taking on more solos and also playing piano on certain tracks. Further changes for the band followed after Ann discovered, just prior to the recording sessions for the band’s fifth album Bebe Le Strange, that Michael Fisher had also been playing the field behind her back.

Ann immediately ended the relationship – now neither of the Fisher brothers were part of Heart. For Ann and Nancy, these were painful times, but the band’s development and potential for future success provided focus. The trauma in their relationships had little effect on the quality of their music; in fact it only seemed to pour gasoline on their desire to be even more successful.

Bebe Le Strange, issued in early 1980, was the last of the truly great Heart albums from the first chapter of their career, racing to No.5 on the Billboard chart – their highest-ever position. The record also unleashed Ann and Nancy’s pent up emotional baggage, following the breakdown of their relationships.

Tracks like Even It Up, Down On Me and Break seemed to speak from the very core of their troubles, especially the latter with its frantic, almost psychotic attack and unmistakable lyrical reference to Ann’s ‘magic man’, Michael Fisher (‘There just ain’t no more magic, man’). Produced again by Mike Flicker, the album was a searing, white-hot lunge at the hard rock jugular. Co-incidentally , the black and white band portrait on the album’s inner sleeve displays an uncanny resemblance to a similar shot used on the cover of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours album.

The album signalled the end of an era, a period that had seen the band go from unparalleled hardship to unprecedented wealth, trading in a broken station wagon for private jets, champagne and caviar. Two further albums followed, Private Audition (1982) and Passionworks (1983) but, perhaps due to the emotional and physical burnout the Wilson sisters were suffering, commercially and artistically the band were firing spent bullets.

Dropped by CBS, it wasn’t until 1985’s Heart album, their first for for Capitol Records, that they regained their mojo. This time, the band would be reinvented for maximum radio exposure, dressed and buffed for MTV. During these years the band experienced even greater success than ever, notching platinum albums and sold-out arena tours by the truckload.

“It was our most successful period,” says Ann. “But soulless, because of the cocaine phase everyone was in. It was a lot shallower and less rewarding, musically. The pressure was on to look and sound a certain way, and to not write your own songs. To take other songwriters’ songs and make hits out of them. If you objected, they wouldn’t help you – there was kind of a Mafioso vibe going on. It all got so bent out of shape.”

“It was a much more ego-driven, less enlightened time for music,” Nancy goes on to say. “All this new digital stuff and imaging was happening – everyone had to look like Prince And The Revolution. It was all about sex appeal again. Someone like Janis Joplin wouldn’t have made it in the 80s. She didn’t have a big haystack of blonde hair, corsets and stilettos.”

It wasn’t until a prevailing wind blew in from their home city of Seattle during the start of the 90s that their winning streak crumbled, but even then they lucked-out when Seattle’s finest newcomers such as Soundgarden, Pearl Jam and Alice In Chains came to their rescue with fervent testimony of their respect for the band, helping to bypass the sort of dismissive vitriol dished out to other corporate ‘hair’ bands.

The rest of the decade saw the band fade in and out of our consciousness. Heart went on hiatus, as the Wilson sisters formed their more folk-orientated spin-off unit the Lovemongers.

Nancy actually quit the partnership, only opting to rejoin her sister in the new millennium for another round of touring and recording. They have since released such well-received albums as Jupiters Darling, Red Velvet Car and last year’s triumphant return to form, Fanatic, which reached back to the very roots of what they had originally aspired to in the early 1970s: damaged electric blues, with songs that actually connected to a new audience as well as existing followers.

“We felt like we were has-beens – going home with our tail between our legs,” reflects Nancy, on those dark years when grunge ruled the roost. “We had forsaken our own integrity to wear all the costumes, the huge hair and the posing. We really felt it was over. But the guys in Alice In Chains and Pearl Jam and Soundgarden stuck up for us. They said we were a huge influence on them. It was great community spirit. And it was good to be in city where music was thriving again.”

Earlier this year Heart were inducted into the prestigious Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. This was from a committee that normally shuns heavy rock music in favour of critical darlings such as the Velvet Underground, U2, REM and Madonna.

As usual, the show was not without its controversy. At the previous year’s induction of Guns N’ Roses, Axl Rose refused to attend and play with his band. In fact, the ceremony has a rich history of musicians squabbling with their bandmates in the run-up to their induction, and on paper, Heart showed every indication of being such a case.

The group had been asked to play at the ceremony. With all good intentions, the sisters graciously invited the original band members to attend and play with them. This would be the first time they shared a stage together since 1979, and the situation was awkward to say the least. Ann and Nancy had washed those men right out of their hair 30 years ago. So how was the reunion for them?

“It was a little awkward,” admits Nancy. “The toughest thing was to feel the vibe. You could’ve cut it with a knife when we walked into rehearsals. It was a real concern.

“Those guys have been doing tribute things for quite a while, especially Roger, who’s been doing his own show,” she continues. “They’ve been going on local radio trying to talk up a reunion, and that’s not something we are going to do – we have a really great new band called Heart. The original line-up lasted for only around five years, but the current line-up is our favourite ever.

“We didn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings, but we had to talk about it and say that getting back together is not something we’re interested in doing. So, once we got past that, there was some politics as far as the rehearsal. We were just going to play that one song [Crazy On You]. They were stressed out about being the first ones in the room. Actually, they didn’t want to be there when we arrived so it was a strange power struggle and management had to get involved. Everybody had to juggle for position a little bit. But it was really easy to meet up with Howard [Leese], he’s always been a good friend.”

What song did they want to play?

“They wanted to do Barracuda, but the Hall Of Fame didn’t want that. So they were disappointed. Nevertheless, they got to stand up there and be seen by a lot of people and get the glory that they deserved, be acknowledged and recognised for their founding contribution.”

“We did one day of rehearsals off-site before the actual day of the show,” reveals Ann. “On the day we had an on-site rehearsal as well. So we did have a couple of times to play before the performance was taped. The off-site rehearsal to me was the most nerve-racking because we hadn’t seen those guys for so many years. We’re all different people now, and all we have in common are 30-year-old memories and, of course, really difficult break-ups, along with all the legality of that; the name of the band – all the kind of terrible stuff that has to happen when you separate, such as money issues. So, there were some really awkward moments when we first saw each other again. Then, when we started playing it sounded like the old familiar way and I think we all relaxed after that.”

Had there been any contact over the years, before the Hall Of Fame?

“Roger was a very intense kind of character,” reveals Nancy. “He’s emailed quite a bit with Ann and he’s always trying to get her involved with some project that he’s doing, but we’ve been really busy. She’s been very cordial to be in touch with him. Myself, I’ve just never felt that need to be in touch – I was sort of done with that part of my life and ready to move on and not to relive the past.”

Did you achieve any sort of closure?

“I think it would take more than two days for it to be truly cathartic,” says Ann, “but yes, there were little moments of closure. I had a cool conversation with Mike Derosier, where we looked each other in the eye and talked – that was great. But, you know, some things in life just don’t get sorted out. It’s not like in movies, where there’s always going to be a happy ending. It just doesn’t happen that way.”

Would you do it again?

“They are all good guys and they’ve gone on to good lives – we all have. It was cool to get play together again and remember that thing we had back then. As far as repeating that experience, I find that highly doubtful. I just don’t see how that would happen.

“They’d have to pay us a lot of money to do that [laughs].”

On reflection, Heart should be remembered as a band that moved things forward for women in the 70s. Fronted by two powerful and intelligent musicians, they predated the vacuous ‘girl power’ malarkey peddled by much manufactured female-fronted music. By actually writing and recording their own material, and taking ownership of their future at a time when such manoeuvres could easily have spelt disaster, or at the very least the end of their career, they proved their mettle.

To imagine a world without Heart is to imagine a world without many of the now hugely prominent female performers who have followed in their wake. For that – not to mention a discography that still thrills to this day – they can be proud.

This article originally appeared in AOR #9.

For more on Heart, not least where to start in their extensive catalogue, then click the link below.