“John Bonham was at the bar drinking quadruple brandies. He just turned around and whacked Gary in the stomach”: The crazed tale of the Heavy Metal Kids, the cult rock’n’roll hooligans with a tragic TV star singer

The Heavy Metal Kids were the missing link between David Bowie and AC/DC

Tougher than glam rock and pre-dating punk by a couple of years, the Heavy Metal Kids were swashbuckling rock’n’roll pirates fronted by doomed livewire Gary Holton. In 2004, Classic Rock traced the story of a band who deserve to be way better known than they were.

The tale of The Heavy Metal Kids is a rags-to-rehab saga of comedy, drama and tragedy. Stranger still, it has recently gone full circle with the addition of some new chapters, though minus its central character.

Fundamental to this story is the London-based band’s choice of name, a tongue-in-cheek and rather ill-suited monicker that its five members were initially partial to, but which would prove to be a curse as well as a blessing.

The Kids (as they later preferred to call themselves) were simply ahead of their time. A riotous, hell-raising collection of rock’n’roll rebel-rousers who not only went on to befriend punk rock icons like the Sex Pistols and The Damned, but also inspired those bands musically. Indeed, The Kids’ flamboyant, high-energy rock has been cited as the missing link in the story of Britpop.

At the eye of their hurricane was a singer now infinitely better known as a TV star. Those who knew Gary Holton say that – carpentry aside – he didn’t have to act too much to portray Wayne Winston Norris, the skirt-chasing, beer-swilling, loveable rogue who charmed the nation in the brickies-abroad TV comedy Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. It’s common knowledge that Holton died of a heroin overdose in 1985. Less known is Gary’s musical career, one worthy of considerable note.

A quintet comprising Holton, guitarist Mickey Waller, bassist Ronnie Thomas, keyboard player Danny Peyronel and drummer Keith Boyce, The Heavy Metal Kids were born 30 years ago in typically bizarre circumstances. Mickey Waller and Ronnie Thomas had been with Heaven (a band billed as England’s answer to Blood Sweat & Tears), but their prospects were fading fast. Under the guise of a farewell gig in Southend, Heaven collared Keith Boyce as replacement for their Glitter Band-bound percussionist, loaded the Transit with equipment, and fled from their manager’s winding-up order to take up, of all things, a residency in an Indian restaurant in the South of France.

“It was playing Rolling Stones covers to 20 customers a night in Nice,” Boyce recalls. “But it lead to some better gigs in St Tropez.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

A paternity suit kept their singer in France, but Heaven had to return home at some point. In need of a new frontman they turned to Gary Holton, of the band Biggles, who despite a raucous cockney accent had joined the touring company of the hippie musical Hair two years earlier, aged just 17. Holton was becoming unhappy with Biggles’ progressive rock pretensions.

“They were like Emerson Lake & Palmer. In fact Carl Palmer’s brother Steve was their drummer,” Ronnie Thomas divulges. “We’d smoke dope and watch Gary rehearse with them, caterwauling above all this synchronised jazz rock. Like us, he was a complete looner.”

“Biggles had a huge record deal but had never recorded a note, just like Heaven,” Boyce adds sagely. “They blew their entire advance; never even did a gig.”

The addition of Argentina-born keyboard player Danny Peyronel from The Rats completed the line-up.

“My American accent soon became a cockney one, but until then Gary and Mickey put me through hell,” Peyronel winces. “When I spoke ‘correctly’ I became one of the boys. It made me realise that Gary could be sharp and obnoxious, but also the nicest guy you could wish to meet.”

Thomas recalls Ricki Farr, the band’s manager (whose boxer father Tommy once fought Joe Louis), suggesting the group call themselves The Heavy Metal Kids (from the writings of William Burroughs). The choice was viewed as a masterstroke. But it would backfire.

Co-manager Laurie O’Leary secured The Heavy Metal Kids a regular gig at his club The Speakeasy, a notorious London hangout for musicians and music biz employees; Keith Moon, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and Bryan Ferry were all regularly spotted there. Despite the clientele’s often blasé attitude, the band knocked themselves into shape.

“It was a great practice ground for us, and for Gaz in particular,” Peyronel explains. “He’d holler: ‘Oi! Fucking listen!’ The only other time I saw the place react the same way was to Bob Marley & The Wailers.”

Having been spotted at the Speakeasy by a secretary of Dave Dee (of 60s hitmakers Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich fame), who was then general manager of the new Atlantic Records office in England, the quintet began to attract label interest.

“They were young and raw, but there was nothing quite like Gary Holton in full flight,” Dee recalls. “He’d wander around in a pair of wellington boots – well before Freddie Starr – and a top hat. So Phil Carson and I decided to sign them [for Atlantic], but on a low-key level. What attracted us was that they were all characters. Besides Gary they had Mickey, another legend in his own lunchbox.”

“You’d be halfway up the M1 on the way to a gig, and Mickey would’ve forgotten his guitar,” Ronnie elaborates. “He’d run up huge bar bills – cognac, everything – but have no money to pay. To this day he lives in Paris and is banned from most bars in the city.”

Dave Dee produced the band’s self-titled debut in a whirlwind eight days (while The Eagles were working on their ‘Desperado’ album in the studio next door). But there was already a problem.

“Gary had begun shoving gear up his nose, and he and I fell out in the studio,” Dee explains. “The others were pretty solid blokes, but Gary was a loose cannon. In the studio I lost a stone and a half in weight.”

When The Heavy Metal Kids’ eponymously-titled debut album was released in 1974, the tracks Ain’t It Hard, Always Plenty Of Women and Rock ’N’ Roll Man captured much of the band’s live ebullience. Though not a huge seller, it upped the band’s profile immensely. The Heavy Metal Kids broke Jimi Hendrix’s attendance record at London’s Marquee club.

They then began gigging across Britain and the Continent to what Peyronel describes as “exhaustion point”. They played more than 300 gigs per year; Melody Maker acknowledged them as “the hardest working band in showbusiness”. At an early gig at London’s plush King’s Road Theatre they hired a fire-breather as their opening act.

“It was a girl, actually,” Peyronel recalls with a smile. “Very exotic-looking.”

Although the Heavy Metal Kids album sold reasonably well, the group found themselves in a vacuum. “There were all these bigger bands like Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Uriah Heep, and then there was pub rock like Be-Bop Deluxe. We were kinda of in the middle,” Peyronel observes. “We supported Heep and Humble Pie, but half of the audience was still out in the Hammersmith Odeon foyer drinking. It didn’t feel like we were getting anywhere. It was much, much different when we got over to tour America. Kids over there would drive 100 miles to see you and were willing to give you a chance.”

Perhaps for that reason – possibly for the sheer devilment – The Heavy Metal Kids got a reputation for ‘rearranging’ hotel rooms. They were banned from the Holiday Inn, Trusthouse Forte and Ramada hotel chains as rooms were flooded, furniture destroyed, kitchens and bars stripped of food and alcohol.

“In this country you can’t get a ham sandwich after eleven o’clock. We’d all bowl back after a great gig high as kites,” Thomas recalls. “We were raiding the kitchen one night when suddenly the lights went on. Gary overtook me on the stairs, with a string of raw sausages hanging from his pocket. When I got to the room he was trying to flush ’em down the toilet, hiding the evidence.”

But The Heavy Metal Kids outdid themselves the time their road crew snaffled a 15-foot Christmas tree from the reception of Torquay’s Holiday Inn.

“They took it out of the pot and bent it in half to get into the lift. There were all these birds in our room, so it was party time,” Thomas remembers. “We’d plugged all the Christmas tree lights in when ‘bang, bang, bang!’, hotel security were knocking at the door and accusing us of nicking their tree. We tried to deny it, but there was a huge trail of mud from the lift to the door of our room.”

By the time of the band’s second album, 1975’s Anvil Chorus, there had been many changes – not all of them for the better. Mickey Waller had been replaced by the enigmatically named Cosmo, and Andy Johns had taken over as producer. Even the latter was an afterthought, his brother Glyn (Led Zeppelin/Free/Rolling Stones) having been first choice.

“Andy walked in with Gary on the first day, and Andy collapsed on the floor,” Boyce remembers. “They were both pissed.”

According to Peyronel, Waller’s departure was highly significant. “The magic was affected. Okay, Mickey sometimes played out of tune,” he muses, “and maybe he also drank too much, but he was the quintessential Heavy Metal Kids guitarist.”

Significantly, the band had also decided to shorten their name to The Kids. “It gave off the wrong vibes,” Peyronel reasons. “We weren’t a heavy metal band – metal people don’t think Spïnal Tap is funny.”

Being signed to Atlantic, The Kids crossed paths with Led Zeppelin on a regular basis, even socialising with them from time to time. Peyronel recalls one memorable late-night drinking session in Blake’s Hotel in Chelsea which suggested that cracks were appearing in Zeppelin’s internal relations as

well as their own.

“John Bonham was at the bar drinking quadruple brandies, when Gary went up to him and said something out of earshot,” Peyronel says. “Bonham just turned and whacked Gary in the stomach. When he got his breath back, Gary went up and started: ‘Listen, man, I don’t know what I said…’, and Bonham tries to belt him again. This time Gary was too fast, and ran up the stairs into the street, with Bonham and his roadies chasing after him and shouting: ‘You bastard. Come back here’. It was a scene from Hell.

“They had to put valiums in Bonham’s brandy to calm him down. It was embarrassing,” he continues. “Robert Plant, Ronnie [Thomas] and I were chatting afterwards, and Plant was saying: ‘I’ve had five years of this lunacy. It’s unbearable’. Jimmy Page took Gary home, with Gary milking it for all it was worth. The next day they even made a formal apology.”

The Kids had enjoyed respect from the music press of the era, with Sounds and Melody Maker supporting them from the start. But the New Musical Express was another kettle of fish entirely, slating them at every opportunity. So when The Kids were told that a journalist from ‘the enemy’ (NME) was requesting an audience in their dressing room at Barbarella’s in Birmingham, they organised a welcoming committee. To reach the band’s changing space in the attic, the writer would have to negotiate a steep stairway. A sofa was heaved out on to the landing, and a bucket of iced water prepared. You can guess the rest, right?

“The guys from Judas Priest had been with us, saying how much they enjoyed the show, when we got the word the journalist was on his way,” Thomas says, beaming at the memory. “We dropped this three-seater sofa down on to the poor sod, then the ice water. He was pinned to the wall. We could’ve killed the fucker. But he took it all in good spirit,”

Thomas then shrugs: “We later discovered the guy was actually from Sounds.”

The Kids’ notoriety took another welcome boost when TV show Panorama shot them playing The Cops Are Coming at the Fulham Greyhound pub. Reporter Julian Pettifer interviewed the audience about violence at rock concerts, and received a suitable response from two fans in particular.

“Chub and Andy came to all our gigs in top hats and Clockwork Orange outfits,” Thomas chuckles. “They went: ‘Violence, you want violence?’ and nutted this guy, who worked for The Times. Sent him sprawling.”

Consequently, local councils banned them from municipal halls. The promoter of a gig at Biba’s in Chelsea also had no idea what he’d let himself in for. “These yuppies were eating a sit-down meal until The Cops Are Coming, when Gary really let rip,” an eyewitness remembers. “He was holding up this fake head dripping with blood, leaping over the tables. It’d been specially made at Madame Tussaud’s and modelled on his own face. There was claret dripping into people’s prawn cocktails. It was brilliant.”

Holton’s showmanship certainly wasn’t lost on Alice Cooper, whom the band then opened for in America. The Kids played one memorable show in front of an audience of 82,000, and Alice regularly watched them from the side of the stage. They also played some shows with Rush, although a run of dates as support for Kiss ended abruptly.

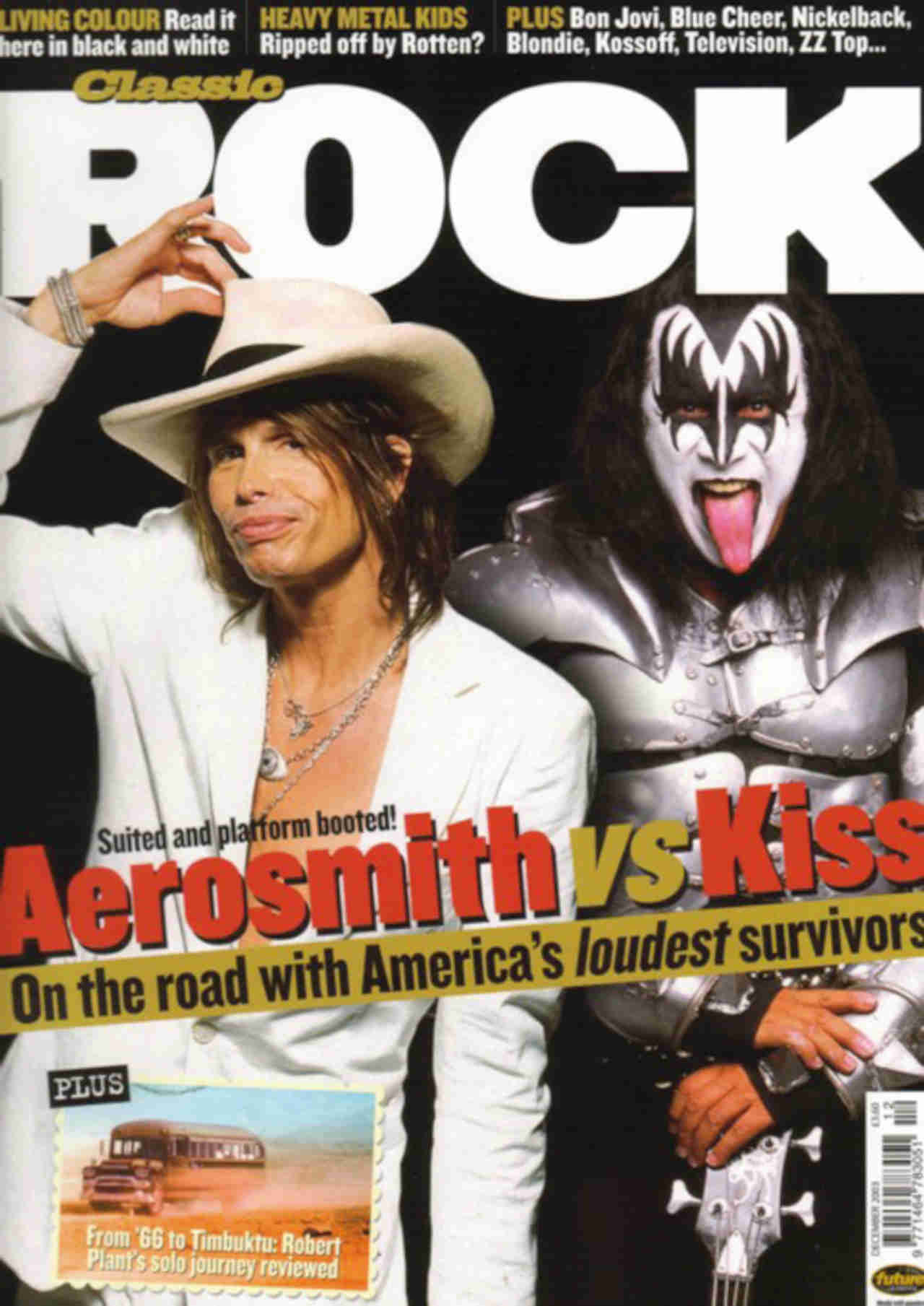

“We were kicked off that tour, and we didn’t regret it for one moment,” Peyronel admits. “There were two incidents that they took objection to. We arrived early at the gig, and talked to some kids who’d been hanging out and buying us drinks. Kiss later claimed that we’d pretended to be them, because nobody knew what they looked like at the time.

“What they really objected to was when Gary and I stood at the side of the stage, and Gene’s hair caught fire,” Peyronel smirks. “He dropped to his knees and whacked his head against the floor to put it out. We were in hysterics. Who wouldn’t have been?”

Later on in the States, Holton’s zany antics caused him to fall from the stage and break his leg. Trooper-like, he continued the tour with his leg in a plaster cast. Peyronel concedes that, growing drug problems aside, Holton’s overpowering presence may have overshadowed the band’s music.

“It detracted from the fact that we were a very exciting rock’n’roll band,” he says. “Gary sometimes went so far over

the top that his outrageous behaviour was all you could see. It was a drag, but you couldn’t really complain because that’s what The Heavy Metal Kids were all about.”

Having severed his ties as producer and record label boss,

Dave Dee was able to rebuild his bridges with Holton.

“I used to tell Gary. ‘One day you will be a star, you’ve just gotta clean up your act’,” Dee reveals. “In fact I tore up a five-pound note. I kept one half and gave him the other, telling him that the day he was a star we’d put the fiver back together and that he could have it. Until about a year ago I still had my half. Gary probably rolled his up and used it for other purposes.”

“People had been telling Gary he was the band’s star, and that he didn’t need us,” Keith Boyce says. “He became too big for his boots.”

Finally, on the same night in 1976 that headliners Uriah Heep ejected singer David Byron from that band – and for the same reasons – The Kids sacked Holton after a gig in Madrid. By then he no longed attended rehearsals, and the band felt he was dragging them down. Breaking into his room, they found him naked and comatose on the bed, with a bottle of brandy in hand.

“We covered his dick with some Uriah Heep stickers, wound a toilet roll around his head and put on him these ladies’ silver stilettos he’d taken to wearing, then carried him on the mattress down in the lift,” Boyce recalls with a smile. “We left him in the lobby, on a big, round table.”

Discovered by hotel chambermaids the following morning, Holton was arrested. The Kids didn’t actually tell him he was no longer their singer, but he got the message.

Three months later, after numerous unsuccessful auditions, the band invited Holton to return. By then, growing friction with Cosmo had caused Peyronel to quit and join UFO (he appeared on their No Heavy Petting album in 1976).

Peyronel had suggested John Sinclair of the Jackie Lynton Band as his replacement in The Kids. Peyronel still feels he was forced out unnecessarily.

“I still can’t believe we agreed to let Cosmo join,” he says. “He was completely wrong. We were a band that had shunned virtuosity, but he wanted to show the world how good he was.”

With newcomer Cosmo campaigning for Peyronel’s to be given the boot, the latter found himself in a resign-or-be-sacked scenario. He reluctantly took the former option. Then, confirming that there was little rhyme or reason to the

group’s thinking, Cosmo himself was then replaced by Barry Paul. Considering the group “unmanageable”, Dave Dee and Atlantic happily sold their contract to RAK Records. Mickie Most had fallen in love with the band, throwing himself into the task of producing what would become 1977’s swansong, Kitsch. Material like She’s No Angel’, Chelsea Kids and Squalliday

Inn ensured that Kitsch remains hugely popular among the fans.

Sinclair’s arrival, along with with Most’s slick production, gave the group a new flavour. Most actually spent six months mixing the record in private, adding extra orchestration and even bringing in members of Smokie to sing backing vocals.

“The album almost became an obsession for Mickie. But it still sounded shit to me,” Thomas insists. “I stayed in contact with Mickie, God bless his soul, and a few years ago he invited me to his gaff. The port and cigars came out later in the evening, and so did the reel-to-reel tapes. Unmixed, it sounded fucking great.”

During a performance at the Rainbow Theatre in north London, Captain Sensible and Rat Scabies from The Damned engaged Holton in a realistic prestaged fight, dragging him off screaming into the venue’s wings. The Damned guys were big fans of The Heavy Metal Kids and “sometimes they even followed us in a van when we were out on tour,” Peyronel says. “I still don’t know why.”

Another personnel upheaval followed when Sinclair left to form Lion (he later joined Uriah Heep). But instead of another keyboard player the band appointed second guitarist Jay Williams.

Success at last seemed within their grasp; the She’s No Angel single even secured them an appearance on Top Of The Pops. Then, without warning, Holton decided to form his own band.

“It really fucked us off,” Thomas says with considerable understatement. “Gary had been a good mate, but he was doing more drugs than ever and becoming really obnoxious. I’d been the best man at his wedding, but he was turning into a nasty little bastard. And on stage it all went out the window; he’d just do whichever song came into his head.”

After a gig on the Isle of Man – the proceeds from which were squandered by Holton in a casino – Keith Boyce decided that enough was enough. Thomas soon followed suit. But both were persuaded to play one final show – at The Speakeasy, where it had all begun. That farewell gig was as memorable for the faces it attracted as it was for the simmering dressing-room tension.

“As Gary was getting ready to go on, he was wearing white cowboy boots with spurs, no trousers and a pink posing pouch,” recalls a still gobsmacked Thomas. “Across his chest he actually had two bullet belts. Gary was then attempting to load this Smith & Wesson revolver; he was completely out of it, bullets were scattered all over the floor and roadies running in and out. I mean, people were trampling over live ammunition.”

In the front row at the gig was Johnny Rotten, who loudly and theatrically pronounced: “boring, boring, boring” to anyone within earshot. But The Kids had already made an impression on the Sex Pistols frontman. Which was proved when he passed on his approval in rather more private circumstances.

One night in the Roebuck pub in the King’s Road, a hush had descended as Lydon and Holton spotted each other in an upstairs snooker room.

“Gary was holding court with me and a group of others by the fireplace, when the atmosphere suddenly changed,” Thomas remembers. “Rotten had walked into the room with two big bouncers – he always had to be protected because he was such an obnoxious little cunt. There was a deathly silence. Finally, Rotten undid this huge gold safety pin and put it on Gary’s lapel. He then patted his cheek and said: ‘You’ve been ripped off, Holton. How does it feel?’”

Even though Peyronel had been forced from the band he loved by that time, he still feels that he and The Heavy Metal Kids were cheated, to use a famous turn of phrase. “What happened to the Pistols in ’77 should have been us,” he says ruefully. “We were one of the first bands to have the term ‘punk rock’ used to describe us.”

That fact was not lost on The Damned, who once invited Holton to replace their singer Dave Vanian when the latter couldn’t make it for a gig in Scotland. The ensuing shambles was still being spoken of in hushed tones when bassist (and future UFO member) Paul Gray joined the band.

“Vanian had pulled one of his disappearing tricks, I believe. So at the last moment Rat [Scabies, Damned drummer] got in contact with Gary,” Gray relates. “En route to Glasgow, the first stop was an off licence. It’s a fair old trot from London to Scotland, and lyrics went flying out of the window along with empty cans. When they arrived to play, Gary could only remember the title of one song, which happened to be Neat Neat Neat, repeated ad infinitum until, unsurprisingly, bottles started flying.”

Nevertheless, until it was cancelled Holton was to have been part of a February 1978 show at London’s Music Machine by the Greedy Bastards, a group that the mere mention of their line-up – Scabies, Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott and Gary Moore and Jimmy Bain of Rainbow – would cause liver surgeons to scrub up and put on their plastic gloves in anticipation.

Holton would subsequently form the band Casino Steel, and even considered by AC/DC as a replacement for Bon Scott, although his addictions made him too much of a liability. The singer discussed assembling a new group with Del Bromham of Stray, but by then his acting career was flourishing. He a had role in the 1980 movie Breaking Glass, which also starred Hazel O’Connor, and had played Eddie Hairstyle in The Knowledge, a TV comedy about London cabbies.

In 1983, Holton signed to play king-birder Wayne Norris in Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. The first series became hugely popular, and Holton’s character was central to it. But on October 25, 1985, when filming of the second series was underway, Holton died of a heroin overdose. Holton had shot some scenes, but others had yet to be filmed. In the end, his final scenes fetured a stand-in.

Dave Dee was at home when he heard of Holton’s death. Having bumped into Gary a few months earlier at the Reading Festival, Dee was mentally prepared.

“He’d been with Glen Matlock [original Sex Pistols bassist] that day, all over the bloody shop,” Dee says. “With somebody larger-than-life like him, tragedy was always likely.”

Holton’s death looked as though it ruled out any further Heavy Metal Kids action, and so it proved. At least until the new millennium. By this time iving in Milan, Peyronel tracked down Thomas and Boyce in order to float the idea of recording a few songs. Nobody thought for a moment that the trio could become the Heavy Metal Kids again. But as new guitarists Marco Guarniero and Marco Barusso entered the picture the project gathered pace. Peyronel had sung with his post-UFO band Tarzen (recording an album with them at Jimmy Page’s Sol Studios), and had no hesitation in stepping up to the microphone as well as playing keyboards. The result was the end of what the band call “the longest tea break in rock’n’roll history”, and also the birth of an album called Hit The Right Button.

Rather than attempting to recreate past glories without their late singer, Hit The Right Button instead but a contemporary spin that placed it close to modern bands such as The Datsuns and The Wildhearts.

“The nicest thing is that people don’t think we’re a bunch of old farts playing the blues,” Thomas insists. “Close your eyes and we could be in our twenties.”

Older and wiser, but no less charismatic, the band’s off-stage demeanour has at least changed for the better. “Keith used to be an animal,” Peyronel says. “Now he empties the ashtrays in his hotel room before he checks out.”

Even Dave Dee has returned to the organisation, this time as manager. He admits: “The reviews all say that Hit The Right Button is an excellent record, but we know it’ll be hard for the band. Basically, they’re gonna go out on the road and start again from scratch. They’ve got a fantastic product… sometimes all you need is a bit of luck.”

And don’t The Heavy Metal Kids deserve a slice of good fortune after all this time?

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 60, November 2003

Postscript: Danny Peyronel and Ronnie Thomas left the reunited Heavy Metal Kids in 2010 and 2011. Keith Boyce is still a member of the band

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.