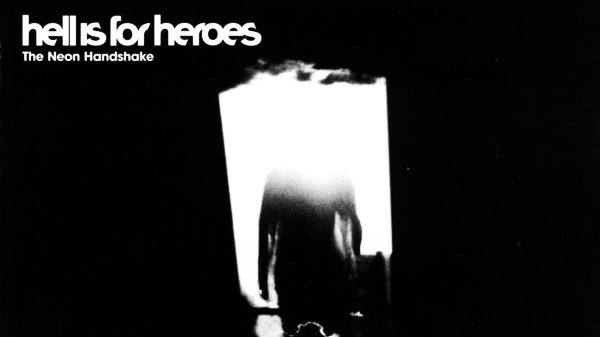

Hell Is For Heroes: How we made The Neon Handshake

Hell Is For Heroes guitarist Will McGonagle remembers how they made The Neon Handshake, the album that would launch their career

If you were in any way involved in the British underground rock music scene of the early 2000s, there’s little chance you weren’t familiar with London-based post-hardcore band Hell Is For Heroes. With their debut album, 2003’s The Neon Handshake, the five school friends propelled themselves from the capital’s dive bars to enviable positions on festival stages around the world, racking up a legion of devoted fans along the way.

“Some bands can go around forever and nothing ever happens for them, but things started to happen really quickly for us,” guitarist Will McGonagle tells TeamRock over the phone from his home in London. The band are currently gearing up for the final dates of a mini-tour in support of the album’s 15th anniversary, and as such, their early journey is fresh on his mind. “Our demo was pretty good and we’d played tons of shows – that was pretty much always our mantra: to play as many shows as we could, not take any days off and just smash it out. I suppose that helped to raise our profile enough that when the press did take an interest, they could see that something was going on.”

To those watching from the sidelines, and for the band themselves, their success seemed to snowball overnight. “We were all working regular jobs when we started,” says McGonagle. “But when we signed to EMI, we all stopped working and started doing the band non-stop. I suppose we were signed for about a year before we went and camped out in LA for six months, and set about recording the album.”

“We started recording with a couple of different producers, just trying to search for the right vibe. The album wasn’t really sounding as raw and heavy as we wanted it to – there was just a little bit too much polish for us. All the while, we kept saying we’d like to try these two Swedish producers, Pelle Henricsson and Eskil Lövström. They’d done some records that we’d liked; I suppose the most famous one would be The Shape Of Punk To Come by Refused.”

Once they had their producers in place, the rest, as they say, is history. “We went into a rehearsal room opposite the recording studio first and just played all the songs over and over again, constantly tweaking it and getting tighter and tighter,” recalls Mcgonagle. “The two Swedish guys worked us quite hard and whipped us into shape. When the time came to go into Sound City studio, we were big fans of it anyway because it was home to some pretty big records. We were aware that it had an incredible drum room and a really beautiful, sought-after mixing desk, so we were really focussed.”

With the band settled in the studio, the album began to take shape. “The two producers brought a lot of sonic ideas,” says Mcgonagle. “By then, the actual songs were whipped into shape, but just in terms of things like starting with a drum loop, or the sound of that drum loop, or the little bits in between songs. It felt like the first five or six songs all meld into each other and all that stuff that came together while we were recording it. The running order seemed to just take care of itself because of the way the recordings were turning out. Then obviously you’re in this beautiful old studio with other incredible instruments you don’t normally use, so we were just trying to take the time to see if there was anything else that would better the songs – any other little flavours beyond the standard two guitars, bass and drums.”

Though admitting they could be “easily distracted as a band – if there was a beer going anywhere in town, we’d probably leave the studio early to go there”, the change of scenery in LA helped to sharpen their resolve. “We were away from home and away from all our mates. Being so many thousands of miles away worked in our favour I think, because it just meant that we stayed at the studios until nine or ten o’ clock every day, doing 13 or 14 hour days. It was very focussed work.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Not that focussed, though. “We were really really big drinkers back in the day, it was a frightening amount of booze,” laughs McGonagle. “I remember one of the trips we had to do out to Los Angeles around that time, we went to a rock’n’roll drinking gaff called The Rainbow. As soon as we landed, we dumped all our stuff and went to The Rainbow, and were drinking so much that the barmaid ended up not being able to serve anyone else because we were going through rounds so quick. She was like, ‘You guys don’t look like a band, but you’ve drunk more than any of these guys, ever’. There was us, five slightly polite English guys going nuts, and then all these hair metallers around us just posing. I think we ended up getting a little bit of a reputation for being caners, which we kind of encouraged as well. We didn’t think we were particularly heavy, but everyone around seemed to think we were pretty fucking relentless.”

- TeamRock+ Membership is now £2.99/$3.99!

- In Praise Of... Reuben

- Hell Is For Heroes reunite for 15th anniversary shows

- The top 10 best Biffy Clyro songs, as chosen by Hunter & The Bear

With the album in the can, what were the band’s hopes for what it could become? “Our hopes were modest,” says McGonagle. “We were a rock band, which wasn’t entirely fashionable at the time. Just being given the opportunity to make an album exactly as we wanted to make it, and then not mucking up that opportunity was our main ambition. And then when we came back to England with it we just wanted to play as many shows as we could, hoping to get quite high up in the tent at Reading Festival, for example. That happened, and then the next year we might have played Download, so we were hitting all these little markers of a band doing what it should. That was super cool. We took a lot of care of the album, and then we did it justice with all those shows we played.”

As their profile grew, so did their fanbase. Were the band aware of the ripples the album was having at the time? “We could definitely tell that people liked it and it was some people’s favourite records,” says Mcgonagle. “You’re allowed to like more than one album at a time or more than one band at a time, but you’d feel that people who were into Hell Is For Heroes were really, really into us. We were well aware that the message board was super busy, and we’d be selling our own shirts at the shows – even when we were playing some of our biggest gigs, we’d be at the merch stand selling as soon as we came off stage because it’s just the best way to meet people and I think they appreciated the access. There was no barrier between the band and the people who were turning up to the shows. That was something we thought was super important at the time.”

So, how does it feel to be revisiting that time and the album 15 years on? “I still like it, actually,” says Mcgonagle. “We put so much effort into it, and it turned out exactly how we wanted it to, so we can still say 15 years later that we probably wouldn’t have changed a thing. It’s weird, when we started rehearsing for this tour, the songs felt fun to play and it doesn’t feel like a massively dated record. I think it still sounds quite fresh. I’m not sure whether it fits in with what’s going on today, but if you’re putting it on for the first time I don’t think you’d realise it’s 15 years old.”

When looking back with the warm glow of nostalgia, you’d think it would be easy for the band to miss how things were back then. McGonagle isn’t so sure. “I don’t think we do miss much to be honest,” he says. “We did it exactly as it was meant to happen, there isn’t much we would’ve changed for our first album experience. It’s after the first album that you alter the direction that your momentum’s going to take you. Your first album, that’s the first rush of energy of a band and it just takes you wherever it’s meant to take you. There’s nothing really we feel like we should’ve done differently, there’s nothing I particularly miss or regret about that whole thing, it just feels cool to go back there because we’ve left it for so long.”

Still, it must feel pretty special that this music still means so much to people all these years on? “Yeah, it does,” says McGonagle. “Just the fact that at every show now, we don’t have anything new to promote, we’re just playing these old songs. The fact that everyone there knows every word and is belting it out, it’s a really special little experience that we’re having. It feels great to revisit it.”

The 10 essential post-hardcore albums

Why 'The Shape Of Punk To Come' still sounds like The Future

Briony is the Editor in Chief of Louder and is in charge of sorting out who and what you see covered on the site. She started working with Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Prog magazines back in 2015 and has been writing about music and entertainment in many guises since 2009. Her favourite-ever interviewee is either Billy Corgan or Kim Deal. She is a big fan of cats, Husker Du and pizza.