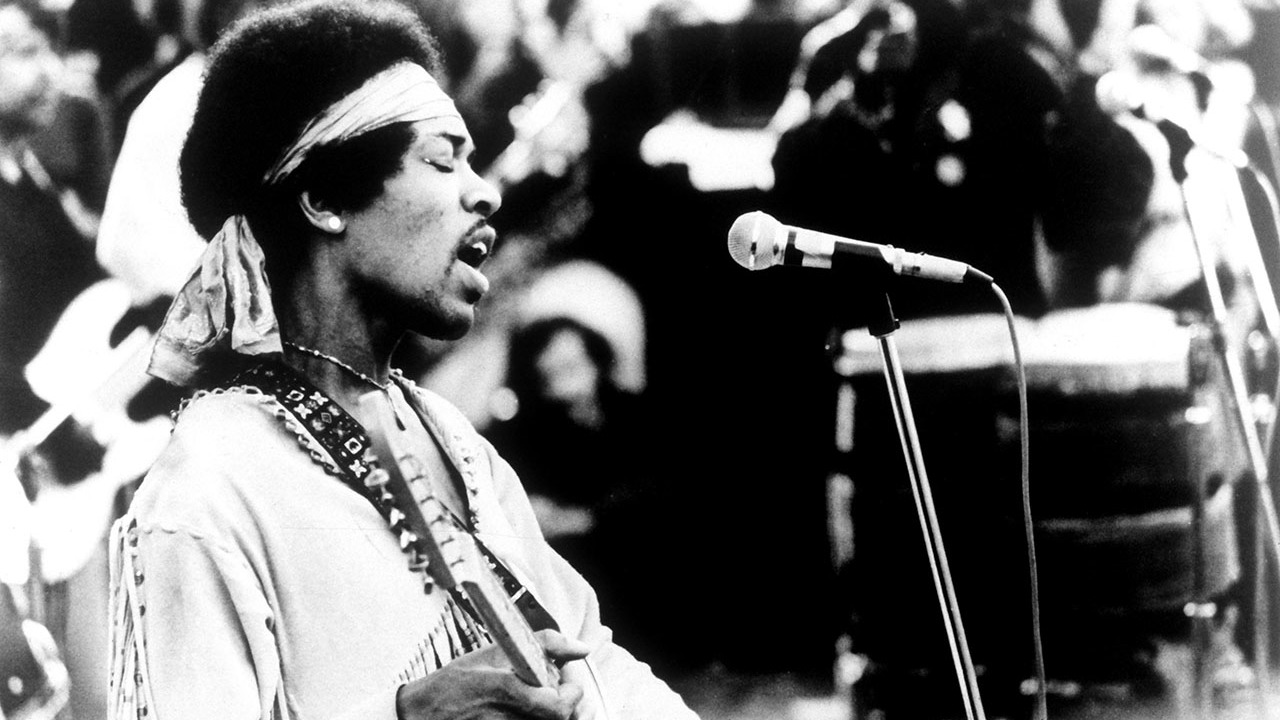

Hendrix at Woodstock is a very different event from Monterey; almost a black light version of it. Like a lot of things – including Altamont – it hadn’t started out that way. In fact his appearance was almost an accident. After the breakup of the Experience the previous spring, he was up in Shokan, New York, putting together his second band and inventing a new extraplanetary sound. Shokan was only 50 miles from Bethel, where Woodstock was held, so it was a convenient – if risky – place to try out his new material and his new band, but then Hendrix was always a high-wire performer who fed on live current.

He was also a true believer in the hippie cloud-nine handbook. He’d named his new band Gypsy Sun And Rainbows, and thought of their sound as Electric Church Music. His opening number at Woodstock, Message To Love, is inspirational, almost a hippie gospel hymn, and he had intended to close his performance with the equally new and prophetic Valleys Of Neptune, switching to Hey Joe at the last minute. He intended his performance to be an optimistic message to his flock, with a few old favourites thrown in.

His so-called big band ensemble – really just the addition of a rhythm guitar player and two percussionists – don’t appreciably affect his sound, neither does his tuning down his guitar a half a step to E flat so he could bend the strings more pliably, but probably makes it a little harder on his new rhythm guitarist, Larry Lee, and bassist Billy Cox. Even breaking the high E string on Red House was barely noticeable – but then who are we talking about?

He jams, noodles, improvises, plays snippets of tunes he’s been rehearsing in Shokan, as well as his iconic songs: Red House, Purple Haze, Voodoo Child, Foxy Lady. But as leisurely as his approach at Woodstock is, he frequently sounds manic and shrill, and even on Spanish Castle Magic his guitar moans and screams as if trying to deliver some terrible message through that torrential rain of notes.

Psychedelic music had once symbolised a transcendent, cosmic vision, but by Woodstock it has become an expression of the national nervous breakdown manifested in Hendrix’s manic,

erratic guitar playing. His virtuoso performances – Fire, for example, played at windtunnel speed – now verge on tonal schizophrenia, perhaps reflecting his own conflicted situation.

Of all Hendrix’s performances at Woodstock, The Star-Spangled Banner, a short interlude in a medley, has come to be seen as emblematic of his entire appearance there: a State of The Freak Nation address, with his guitar like some highly sensitive receiver tuning in to the jangled frequencies in the culture, and ventriloquising the truly terrifying voice of a psychotic Republic. Long shrill wails, crashing bombs, shrieking, screams, automatic weapons. Its precise hysterical outcry resembles Picasso’s Guernica in the sense of how much you can express on an electric guitar. The Vietnam War, burning ghettos, the Manson murders (which had taken place barely a week and a half earlier) are, by implication, invoked with devastating emotional impact, and the horror, despair and lethal irony isn’t lost on the crowd.

Hendrix’s music always had a foreboding quality to it, that spooky crossroads element inherent in the blues, and though he wanted to bring on the Age of Aquarius, Woodstock was the end of something rather than the beginning. His performance turned out to be more of a eulogy for what might have been than what was to come. But who better to sprinkle gris-gris dust on the utopian dream of the 60s than our own shaman of the blues.

Click below to read more…