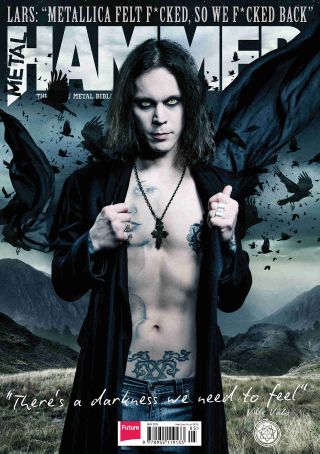

The career of Finnish goth metal icons HIM was nothing if not eventful. Frontman Ville Valo’s well-documented problems with alcohol almost ended with him checking into rehab following 2007’s Venus Doom album. By the time of 2013’s Tears On Tape, it was the turn of drummer Gas Lipstick to suffer an injury that almost ended his own career. Ville invited Hammer into the band’s Helsinki lair to talk tears, trauma and the album that would unknowingly become HIM’s swansong.

In 1835 Elias Lönnrot published The Kalavela, an epic poem based on the songs, oral histories, and colourful pagan mythology he’d spent years collecting from up and around the culturally disparate assemblage of frostbitten regions we now know as Finland. Credited as the first expression of a Finnish national identity, the 22,795-line masterpiece was the crucial first step toward the snowy, windswept country’s declaration of political independence from Russia in 1917, and its magically laced storyline has sparked the imagination of writers as diverse as JRR Tolkien and British sci-fi legend Michael Moorcock.

Today, as the collected members of HIM will explain from the back of a 12-seater minibus currently giving Metal Hammer a guided tour of Helsinki, the preponderance of blue and white Finnish flags blowing in the arctic wind today is no accident, because this is Kalavela Day, a national commemoration of Elias Lönnrot’s literary vision. Unsurprisingly, many Finns choose to ignore days like today as the result of years in primary school having the significance of the Kalavela drilled into them with the kind of bonhomie reserved for guests of Camp X-Ray.

And yet, were Elias Lönnrot alive today, you have to wonder whether the celebrated philologist would include HIM in his story, because in just a few weeks the next chapter in Finland’s biggest export since Hanoi Rocks’ ongoing saga is about to begin. So then, shouldn’t we be having a Kalavela barbecue or something?

“Fuck no,” snaps Ville, lighting a cigarette and smirking. “It’s a big day for Nazis and black metallers. Let’s hit our studio instead. It’s our place of turmoil, and…” he pauses, a Cheshire Cat grin spreading across his chiselled features. “Let’s call it our place of resurrection.”

If there’s a hell for OCD sufferers then it probably looks something like HIM’s rehearsal room. Secretively tucked away in the upper bowels of one of Helsinki’s better-known rock venues, it’s in this artfully decorated shithole that HIM have gotten their sweat on to the tune of over eight million records sold.

For the last 10 years it’s been their hub of writing, demoing and readying for whatever gig or tour sits on the horizon. Strewn about the ceiling-high valve amps and the kind of bizarre detritus you could only accumulate from years on the road are endless tangles of cables, power strips, and strange-looking analogue recording equipment. An ancient setlist is scrawled on a wall by a velvet Lenin, a large assortment of brassieres betray no secrets as they hang from a large neon drink sign, and everywhere – but primarily on keyboardist Burton’s comically oversized console – are ashtrays overstuffed with fag-ends from days and nights spent here in exile from Helldrinky’s many avenues of excess.

Aside from local compatriots Amorphis, who occasionally share this space (and who Ville grumpily refers to as “fucking Amorphis” based on the number of beer cans discarded on the floor from a session the night before), we’re the first outsiders here, and yet this visit’s as spontaneous as any visit to a local pub. A signed, framed glossy of Chris Isaak which Ville is particularly proud of sits atop a disused piano, and beside it is a fake human skull covered in hair which, as bassist Mige proudly explains, enjoys status as the band’s most valued totem.

“That’s all taken from our heads,” he explains with the enthusiasm of a kid-brother grossing out a tortured sibling. “We’ve glued it on there over the years. It just seemed like a good idea at the time, but it’s brought us a lot of luck.”

Precisely how much luck it’s brought is debatable. It’s here that the story of how HIM’s new album, Tears On Tape began, curiously, with an event that stopped their 20-year ascent dead in its tracks, and forced the quietly spoken quintet to question their motives as artists and as friends, and it’s a tale of loyalty and karma repaid that would have easily seen lesser bands dissolve under the strain.

It was two summers ago, when, in the middle of a writing session for the follow-up to 2010’s Screamworks: Love In Theory And Practice, that drummer Gas Lipstick stood up and confessed he couldn’t do it anymore. Far from a statement of desire, a fire-like pain in his right arm – the result of endless repetitive stress placed on it by relentless touring and his superhuman proclivity for taking on side-projects – had become so paralysing and unbearable that the lifelong sticksman could simply do no more. With that uniquely Finnish mastery of understatement, he simply revealed one day that he couldn’t do it anymore.

“We’d started working on riffs and new ideas and suddenly it seemed like Gas wasn’t doing so well, and he was playing a bit quieter,” says Ville, looking serious as he recalls the doomed day. “We were like, ‘If something’s wrong go to a doctor.’ And he was like, ‘Nah, it’ll be fine.’ By the next rehearsal we were in the middle of a song and he just went, ‘Guys, I can’t play anymore.’ It was out of the blue. It was like he didn’t want to spoil the vibe of the band by complaining about it. I wish he had.”

What would follow would be a life-sapping period of inactivity for the group as their longtime friend would be relegated to the sidelines under doctor’s orders to do nothing. As Ville recalls, an acutely frustrating trial would follow whereby every few weeks a specialist would examine Gas’s arm and, heartbreakingly, recommend another six to eight weeks of total rest. According to the assembled troupe, it’d have been different if it was a year off, but the hurry-up-and-wait nature of the prognosis held them in a hostage-like stasis that began to drive them bonkers: no gigs, no rehearsals and no progress.

Ville has never been one for the passenger-seat, insisting on approving every aspect of HIM’s career from tour-routing to merch-designs to dissecting every note of recorded output to the nth degree. For over 20 years being in band has been his sole endeavour, so you wouldn’t be wrong for asking yourself why they didn’t just recruit someone else, but then there’s more to Gas than his almost obsessive love for Dave Lombardo or his formidable abilities honed in deathgrind projects like To Separate The Flesh From The Bones. Sure, his playing anchors HIM’s unique brew of heavy-riffing melancholy in the world of metal, but there’s more to it than that.

The answer to their conundrum came many months ago when the band themselves asked the very same question, not out of impatience, but because Gas’s overriding sense of guilt at the holdup was doing him no favours. Solemnly, the group gathered in this very space to face a very difficult question: not whether to fire Gas, but what kind of people they were.

“We had a very fateful evening,” says Ville, twirling a cross around his neck. It belonged to his mother and contains a key to a long-lost diary. Naturally.

“We started speculating what to do, and all of a sudden everybody became so emotional. You try to figure stuff out intellectually – to solve this puzzle, but it falls pieces when your heart starts talking and emotions get involved. It was a very big deal, it was devastating,” he says, clutching at the large, brass crucifix. “You’re waiting for months at a time, rapping your fingers on armchairs, and thinking of what you’d rather be doing, and thinking of poor Gas. He’s been drumming since he was five, we’ve known him since we were kids. We had that meeting and we were weeping like little babies, trying to figure out if to continue, and if so, how? Obviously if I got hit by lightning I’d want the guys to continue. The show must go on…”

But where lightning may have spared these modest troubadours, they’ve not been without their share of career-threatening strife. As documented in these very pages, it was just a few short years ago that HIM faced their greatest challenge when, one day in May of 2007 and having just released their sixth album Venus Doom, Ville checked himself into rehab after being told by a doctor that months on the lash had left him so dehydrated that his body was shutting down.

A calamitous headliner at London’s Earls Court a few weeks before had left many wondering whether it was the end for the band whose love for the growl of Sabbath and the forlorn, sardonic wit of Type O had earned them the first-ever American Gold record by a Finnish band. But Ville would recover, and his bandmates would stand by him in a gesture of fidelity that could only be repaid by how the band behaved in the face of their most recent experience of adversity. And make no mistake: there have been others.

“There’s been a tragedy every album,” the baritone crooner admits with his usual, disarming candour. “With Venus Doom it was my insomnia and drink and drugs, because that’s what you do – you start self-medicating, but it’s good to be close to cracking, you should find out what the edge is for you. You can fuck up royally – your relationships, your relationship with the band, being creative, being uncreative, hurting people’s feelings – you don’t fall as hard when you aren’t drinking, that’s all.”

And with that, he grabs a beer from his bag and the band, without forewarning about what’s to happen strike up what must be the smallest HIM gig in history – Buried Alive By Love is storming, and – in these tiny confines, utterly bone-jarring. It’s easy to trip over Linde’s gigantic assortment of pedals before finding a perch near Burton’s keys to get a view of the action. HIM, without blinking, launch into the Stooges-loving tirade of Into The Night with a gleeful, almost punkish abandon before Tears On Tape, lead by Burton’s expansive keyboards, spearheads something anthemic, memorable, and easily the most powerful condensation of the Finns’ inimitable sound since 2003’s Love Metal established their global pre-eminence.

Inches away from a band that’s played to tens of thousands, it’s hard not to focus on Gas and how hard he pounds the skins. There’s something triumphant in the air now, an urgency and insistence fuelling these songsmiths that, as they’ll later confess, isn’t imagined – Tears On Tape, produced by Hiili Hiilesmaa of Love Metal fame, is a record they can’t wait to kick out the door, an amalgamation of so many frustrations and delays that the only thing now is to come full circle.

But it’s with extra gusto that Gas drums, that he powers through – it’s hard not to be moved by the scene, which, reading the faces here – signifies relief and reassurance that they can still do it. They’ve only played a handful of times since shit went down, just once in front of a home-crowd at Ville’s own Helldone festival. For a group shouldering a global fanbase’s weight of expectation, they do it with the aid of a few beers.

At 36 years old, Ville Valo still cuts a striking figure but it’s with the wisdom of someone who’s run life’s gauntlet once or twice that he reflects on his life’s events. He remains, as ever, a master of metaphor, and relates the raw, Sabbath-loving heaviness to having a hot girlfriend who, after awhile, you politely ask to wear some different lingerie. “You still want the girl,” he says, winking. “You just wanna try something new.”

It’s late and, around the corner from Tavastia, the legendary venue that, many years ago, confirmed HIM’s readiness to take the world’s stage, Gas is kicking the living shit out of Ville in a game of pool. It’s here where they blow off steam, where in the rare down-times that they return to the status of mere mortals, where…

“Ville?”

A girl on an adjacent table stops the game and asks for a picture. “I can’t believe you’re real…” she says. The band are obliging, Gas patiently taking the photo, and she returns to her match, her day made. As with the rest of the band, Gas is obscured by a quiet humility, a drive to get the job done and leave Ville to do the talking that slightly overshadows a charming jocularity that perhaps understates what he’s just been through.

“The truth is I didn’t know what I was going to do,” says Gas, whose affability and warmth is infectious. A minute with him confirms why his brethren were so very protective of him beyond his formidable skills behind the kit. “I’ve been doing this since I was a little kid, always hitting things as hard as I could, it was the hardest period in my life.”

Conversation swiftly shifts to Slayer’s recent, painfully public dramas. Ville downs another beer. It’s surprising, but he’s bemused by the mention of wagons – the decision to get sober was, after all, his own.

“I think that you have to play with fire to be alive,” says Ville of his rekindled relationship with Bacchus. “Everybody needs to get burned, and I have, but I’m taking it easy. Cracking open a beer and writing? It’s a perfect drug for creation. The only thing that’s tough, especially for this particular idiot, is to find a balance.”

As we filter out into the cold Helsinki air, he’ll explain how the beating heart of HIM is the friendship that underlies their every decision – while outsiders may view them as a singer and band, these longtime collaborators stand as equals. The solidarity they showed when Ville was at his lowest ebb was the same unity that kept them together through Gas’s tribulation, and make no mistake – it’s far from over. As our breath crystallises in the cold night air, we stroll to one of Helsinki’s many central squares, where the city’s central cathedral casts an imposing figure over the nighttime scene.

“Ah yes, the steps of doom,” he says. “We’ve spent a lot of time there.”

Are you grateful the band stood by you?

“It’s tough to say,” he says, the pained expression on his face making it clear this is still a sensitive subject. “Obviously, you know…” exhaling a plume of Marlboro. “I was highly flattered by the patience, but when you are struggling through your own personal maelstrom you don’t realise what’s going on around you, because you’re in the depths of the abyss. All of our shit’s hit the fan at some point. Whenever anyone needs a pat on the back, a sincere talk, we’re all here for that. That’s real friendship. I see it all more clearly now.”

Of course, the tribulations for this band are far from over. After all, it’s been over two years since their last release and it’d be foolish to simply assume that your fans have stuck around in today’s ever-accelerating carousel of hopefuls. It’s with some anxiety that Ville anticipated the release of his latest opus – in today’s ephemeral world of tweets, status updates and our newly developed, highly detailed awareness of the personal goings-on of our world’s various heroes. And, in case you’re online right now, you’re unlikely to learn what he just had for breakfast.

“Ninety-nine per cent of social media is bullshit,” he says, flatly. “I want to know what world Carl McCoy is creating, what he’s feeling, not what kind of coffee he drinks. I like the fact that I don’t know everything about him.”

So then, what about your return?

“The fact is there’s not a lot to tell – I mean, nothing was going on and then we broke our radio silence, and started rehearsing – we wanted to see if we were still in shape to play, to see if we could still riff, and most importantly to see if we could still smile while we’re doing it. You do wonder if the chemistry is still there, people can drift apart, but that’s not what we were doing

But it’s clear HIM are undergoing something of a resurrection. Tomorrow, they’ll begin shooting two videos with old friend and director Stefan Lindfors, who shot their classic Funeral Of Hearts video, and he’ll require Ville’s full attention. A different man from an earlier chapter may have thrown caution to the wind and plunged into the depths of Helldrinky’s many, many late-night dives. We say our goodbyes and he disappears into the frigid night. It’s clear that only time will tell what the dawn will bring.

Originally published in Metal Hammer 243, March 2013