To a whole generation of rock fans in Ireland, Horslips were the band of their lifetime. Arriving in the early 70s, they created a glorious blend of traditional influences and rock music – and also inspired the way U2 would do things. In 2006, bassist and vocalist Barry Devlin looked back on the band’s long-lasting influence.

Horslips changed my life, and had pretty much the same effect on a whole generation in Ireland. A big statement, but a true one. Back in the early 70s we had Rory Gallagher, we had Thin Lizzy, and we loved them dearly. But we didn’t have rock music that could really be called our own. No one knew what that was until Horslips came along.

What were the magic ingredients that charmed us through Horslips’ 11-album history that started in 1972? It began with a bit of Irish traditional music, but placed in the context of rock music: bass, drums and guitar sitting next to electric fiddle and mandolin, tin whistles, bodhran and, magically, an electric set of uileann pipes (the Irish equivalent of bagpipes). It could have been a recipe for disaster (and many still say it was), but it worked. And it rocked. With that, Horslips brought their startlingly innovative but commercial rock songs, underpinned by subtle Irish traditional nuances, to the nation.

The band’s influences were wide and varied: Jethro Tull, Deep Purple, The Beatles, Steeleye Span, and traditional musos whose names are carved in Irish musical folklore – O’Riada, O’Carolan…

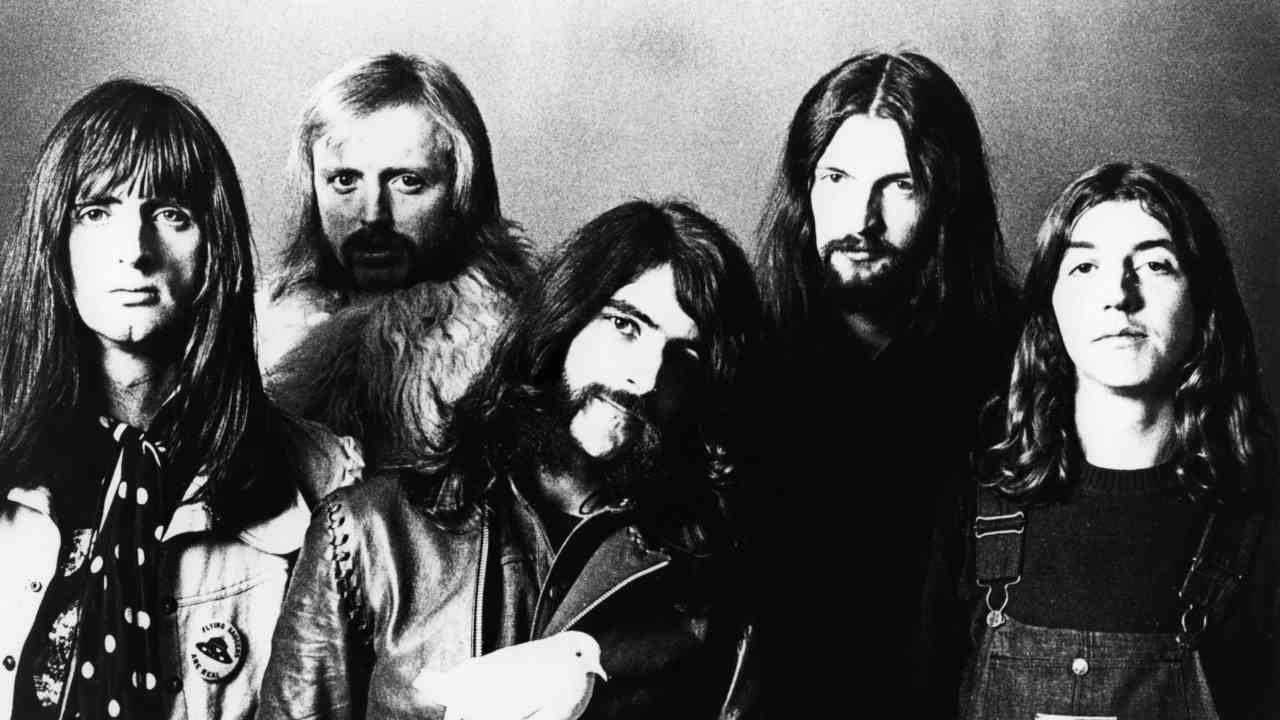

More importantly, this music was being created by people (approximately) as young as we were: Barry Devlin (bass, vocals), Charles O’Connor (fiddle, mandolin, vocals), Eamon Carr (drums, bodhran), Jim Lockhart (keyboards, whistles, uileann pipes) and the truly fantastic guitarist Johnny Fean, the last member to join the band and the only one not to come from an art school environment (Horslips were smart too).

Their first album, 1972’s Happy To Meet, Sorry To Part, recorded in a barn in Tipperary on The Rolling Stones’ mobile studio, set the youth of Ireland alight as Horslips took their battle for supremacy to the dance halls of Ireland, normally the happy hunting ground of showbands who peddled their dodgy sets of cover versions.

As the rookie writer of the Pop Page on the Derry Journal, I was caught up in that first euphoric wave of rock nationalism. Through Horslips I found out what it was like to be a rock journalist – hanging out with the band during rehearsals, touring Ireland and going to parties; finally being encouraged by them to up sticks and join Melody Maker, during which time I went on bigger tours and to bigger parties.

Another youngster at the time who grabbed the vibe was Bono: “Horslips were a great band in the sense that they invented something. That’s my definition of a great band; being great at somebody else’s shit never made you great, even if you’re better at it than the people who invented it.”

“We were young and excitable and we wanted to do something different,” says Barry Devlin now. “Second, that want coincided with the rise of that something different: an awareness of Irish tunes and Irish culture as being grand rather than little. And there was a sense that something – the music and the enigma around it – was ready to move from its serge-suited insularity to a wider audience. I don’t mean wider as in abroad, I mean as in of the spirit. There had been a kind of miserliness about – not its players, but its custodians. We wanted to wrest it away from its custodians and hand it out.

“Thirdly, it was the start of the 70s, when people were trying out new things; rock was flexing a new ‘intellectual’ muscle. Particularly, it meant fusion – jazz rock, classical rock, folk rock. We were hugely enthused by the rhythmic and melodic possibilities of some kind of fusion, and that’s what we went for. And by the time our second album came out, The Tain, we knew how to do it.”

Released in 1973, The Tain, with its great Celtic mythical theme, really struck a chord and showed a band with tremendous creativity. While rock was predominant, the traditional influence always bubbled underneath (a case in point being the track Dearg Doom).

Armed with The Tain, Horslips set off for Britain. They soon made an impact there, winning over critics from NME, Sounds and Melody Maker, supporting Jethro Tull, Procol Harum and Steeleye Span, and soon being proclaimed as the Next Big Thing.

With RCA Records backing them in Europe and Atlantic Records in the US, Horslips soon had a substantial following – and not only from the young Irish Diaspora. Against all the odds and helped by the release of some more excellent albums – Dancehall Sweethearts (1974), The Unfortunate Cup Of Tea (1975), The Book Of Invasions (1976) and The Man Who Built America (1978) – they were indeed a phenomenon of sorts: the original Celtic Tiger.

“We mainly established that you could do it from here [Ireland], and that here was no longer a funny little annex to England,” says Devlin. “We still looked to England far too much in our time on the road. We were breaking away from a mindset, remember. Enough had been done by the time U2 came along for them not to care too much what England thought. Which was just as well, as England didn’t think too much of them at the start.”

In many ways, Horslips were the business model for U2, and the connection – apart from U2’s love of Horslips’ music – was made from the start. Michael Deeny had left a promotional partnership with Paul McGuinness (U2’s manager) to look after Horslips.

“What Paul McGuinness talks about as having been learned from us was an ambition path, a preparation for greatness – taken as read, rather than an economic model,” says Devlin, who produced the first U2 demos. “Unfortunately for us, U2 delivered; we didn’t, largely, I think now, because the music was too Irish, despite what we thought. And also because we hadn’t the good sense to be three beautiful girls [with the surname Corr, presumably] from Dundalk and their brother Jim. With my luck I’d have been Jim!”

Frustratingly, just as Horslips were making major inroads in the US with The Man Who Built America, with the Irish traditional influence now more overt and a definite AOR thread taking over, the band decided to call it a day. Mercury Records in the States loved The Man… but hated the follow-up, 1979’s Short Stories/Tall Tales. Horslips needed to regroup, reenergise and get back to their roots. Instead they walked away from it all.

“You’re correct about walking away,” says Devlin. “We weren’t up for the three more years it would take to recover the ground we knew we were about to lose. We’d toured for nine years non-stop – 230 gigs a year, routinely – and we were knackered.”

As a swansong, they headed for Belfast and recorded The Belfast Gigs, ironically rediscovering their power in an overwhelming set of live music. It was too late, though. Horslips were scattering to the four winds, leaving some unsavoury characters to march all over their catalogue and release all manner of dodgy compilations. (The band members took those characters to the High Court and won back all their rights.)

And so they went their separate ways: Devlin to scriptwriting and directing for TV and movies, Carr to journalism, Lockhart to radio producing, O’Connor to making fiddles, while Fean kept playing guitar. That was until 2004, when a group of Horslips fans in Derry decided to host an emotionally charged exhibition of paraphernalia in honour of the band. Horslips turned up for the launch and played an acoustic set.

They could scarcely have anticipated the media reaction in Ireland; it was all over press, radio and TV. And as the exhibition moved on to more acclaim in Belfast and Dublin, the pressure was on for something else. Hence 2004’s Rollback album, an unplugged-style greatest hits record which has sold more than 30,000 copies in Ireland.

“People always speak well of the dead,” Devlin laughs. “We have become greatly loved since we were laid to rest and our critical evaluation has soared! But, seriously, we’re delighted that we had an effect. I do know it’s the best hobby I’ve ever had.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 98 (September 2006)