Sometimes a breakthrough album becomes such a landmark that it gives an artist the freedom to subsequently do whatever they want. And equally, sometimes the logical next step is to make the follow-up to that breakthrough as similar as possible – a sequel that repeats the winning formula and cements their growing status with their core constituency of fans.

This was the position Metallica found themselves in when planning their fourth album: not just the follow-up to their breakthrough hit, Master Of Puppets, but also their first without bassist and old-soul Cliff Burton. The safe option would have been to make, in effect Master II – to both cash-in on their now established winning formula and prove that Burton’s replacement by Jason Newsted had been achieved seamlessly.

When, however, drummer Lars Ulrich and singer-guitarist James Hetfield came to sit down and talk about it one afternoon in October 1987, while winding through The Riff Tapes – the compilation of ideas that had emerged at soundcheck maybe, or odd musical movements Lars would hum and James would turn into chords on his guitar – they decided not to follow any of these rules and instead go for broke with something so completely different to what had come before as to be virtually unrecognisable from the Metallica template. Or rather, Lars did.

High on the million-selling success around the world of the Garage Days Re-Revisited single EP, and unduly taken with the rule-breaking sound of the debut album from a bunch of LA ne’er-do-wells called Guns N’ Roses, released the same year, he felt the time had come for Metallica to jettison the thrash metal lifeboat and go for a whole new approach. James was inured to Lars’ non-stop talk of world domination and, still lost and unsure how to proceed without Cliff’s bullshit-o-meter to guide them, merely nodded his assent. They would just put the songs together as usual and see what came up, right? Wrong.

Certainly there was nothing new to their approach in that respect, the two working from home alone on a four-track, Kirk Hammett invited down at a later stage to consider his lead guitar parts, Jason not invited at all on the pretext that with only four tracks to work with there was no room for bass at that stage anyway. As a result, of the nine tracks eventually slated for the album – all essentially Hetfield-Ulrich compositions – just three would also bear Kirk’s surname, just one Jason’s, and one had Cliff’s: a posthumous work melded from “some bits and pieces” the bass player had left on tape, over which James intoned a four-line poem Cliff had also left behind entitled To Live Is To Die. In fact, the only big difference initially was the decision to record the album closer to home this time, in Los Angeles, a choice rooted, paradoxically, in a newfound conservatism – at least, away from the stage – and their sudden desire to be close to their various partners.

This was one aspect of their lives the young Metallica went out of their way to keep off-limits from the press, even the almost venally talkative Lars, who became uncharacteristically tongue-tied the first time he introduced me to his English-born wife, Debbie. A fun, fair-haired, girl from the Midlands, the two had met in London in 1984 and married early in 1987, during the brief hiatus when James was still nursing his broken wrist, the result of a skateboarding accident. It wasn’t that Lars hid his wife from the press, it just happened to be one of the very few things he didn’t talk about. Plus, ladies man Lars didn’t like to think of anyone cramping his style and while he clearly loved being around Debbie, the marriage was doomed to end just three years later.

These, after all, were Lars’ wild years and, with the band finally taking off, it was no time to be married to its principle party animal. As he later said, for a while they had considered naming their next album, Wild Chicks, Fast Cars and Lots of Drugs, such was the state of play in Metalliworld at the time. How could any homespun, working class English girl hope to compete with that?

Kirk, too, had chosen just this moment to marry his pretty American girlfriend, Rebecca (Becky), the two tying the knot in December, just a few weeks before the band began work on the new album. From the outside, Kirk and Becky looked like the perfect couple, almost a mirror image of each other, with their long curly hair, elfin faces and large brown eyes. Becky was ditzy, airy-fairy, and fitted in neatly with Kirk’s own public persona as the spliff-sucking, comic book collecting, easy-going hippie minstrel. In fact there was a new edge starting to emerge in the guitarist’s character as he began living out his own rock star fantasies, and cocaine began to match marijuana as his drug of choice. Their marriage too would end after just a few short years.

Jason, who had split from his long-standing girlfriend Lauren Collins, a college student from Phoenix, shortly after joining Metallica, now became involved with a new girlfriend, Judy, who would become the first Mrs Newsted over the coming year, though they got divorced even quicker than Lars or Kirk, deciding they’d made a mistake almost immediately.

The only one who didn’t get married at this point was James and he, ironically, was the one perhaps most deeply in love. Indeed, his girlfriend Kristen Martinez would later inspire one of Metallica’s best-loved songs and one of the cornerstones of their far more widespread popularity in the 1990s, Nothing Else Matters. That, though, was the only time James even semi-acknowledged his affair with Kristen publicly, even going as far as to later claim not to have written the song about her at all, so deep was his hurt when they too broke up in the wake of Metallica’s now rocketing success.

That, however, was in the future. There were no love songs planned for the fourth Metallica album. Instead, Lars was determined to place the emphasis on a new, harder edge. Besotted with the Guns N’ Roses album, Appetite For Destruction, which contained so many swear words radio wouldn’t play it, most of all he wanted to ensure Metallica didn’t get left behind by what he called “the new dicks on the block.” He later recalled listening to the first single from the Appetite album, It’s So Easy on a flight home to San Francisco and being unable to believe the unashamed misogyny of the line, ‘Turn around bitch, I got a use for you…’, nor the pay-off at the end of the final verse when singer Axl Rose yells: ‘Why don’t you just… fuck off!’

“It just blew my fuckin’ head off,” Lars excitedly told James. “It was the way Axl said it. It was so venomous. It was so fucking real and so fucking angry.” It was the start of an obsession with Axl and Guns N’ Roses that would eventually see both bands touring together, though it would not be one shared with James.

When it became apparent that Flemming Rasmussen, the producer who had overseen both Master Of Puppets and its equally barrier-crashing predecessor Ride The Lightning, would not be available as quickly as they would have liked, Lars, secretly delighted, seized on the situation to put forward a more exciting alternative: Mike Clink, the Baltimore-born producer who’d overseen the recording of Appetite For Destruction.

Clink had begun his career as an engineer at New York’s Record Plant studios, assisting producer Ron Nevison on hit albums by soft rock giants such as Jefferson Starship, Heart and, most notably, Survivor’s huge 1982 hit single and album, Eye Of The Tiger. Clink’s main attributes, according to GN’R guitarist Slash, were “incredible guitar sounds and a tremendous amount of patience.” Smart enough to realise the records he’d made before were essentially “pop albums”, he’d listened carefully when Slash had played him Aerosmith albums in preparation for the Appetite sessions. Interestingly, the album Axl had asked him to take special note of had been Metallica’s Ride The Lightning.

With One On One studios in North Hollywood booked for the first three months of 1988, Lars asked band manager Peter Mensch to put a deal together that would bring Clink in as producer on the new album. Clink, a shrewd operator looking for a project that would extend his newfound reputation as the go-to guy for cutting edge rock bands, was intrigued enough by the approach to accept at first time of asking. Nevertheless, on the surface it seemed an odd fit: Clink was known for capturing a looser, bluesy, as-live feel in the studio; Metallica known more for their almost icily precise sheet-metal riffs and machine-like rhythms.

Somehow it would be Clink’s job to marry the two. As he says now: “They hired me because they enjoyed [and] really liked the Guns N’ Roses records.” However, the message he got in his initial conversation with Mensch “was that they do things the Metallica way. And I didn’t really know what that was until I got into the middle of it.”

James was even less sure. He was no fan of the GN’R record. As far as James could see, Clink wasn’t anything special – just another of Lars’s passing fancies. He watched patiently though while they searched for a drum sound that seemed to match whatever requirements were going through both Lars’ and Mike’s heads, then lost patience when it came to his guitar sound. Although they managed to do what they always did at the start of an album and lay down a couple of rough-hewn covers in order to iron out any potential problems – in this case, Budgie’s Breadfan and Diamond Head’s The Prince – instead of smoothing out their differences, it only highlighted how far apart their thinking still was, especially between Hetfield and Clink. “I just flipped out,” said James, “couldn’t hang with it anymore.”

It put Clink in an awkward position. “As much as I believe they wanted me to put my magic on the tracks,” he says, “I think that they were used to doing things on their own and doing it their own way.

“I always felt that I was in the wings, waiting until Flemming got free or they could convince him to work on the record [because] at that moment in time it just wasn’t working… They bristled at someone trying to tell them what to do. And I think it was as much my fault as their fault. You know, I had just come off of the Guns N’ Roses record and doing things my way, and having my say. And I kind of ran into a bit of a brick wall and it was difficult for me.”

Clink also felt that “the absence of Cliff was a little unsettling to them… in the back of their minds maybe they wanted something more familiar, because that was a big step without him.”

Whatever the real problem was, by the end of the third week recording, Lars was on the phone to Flemming, virtually begging him to rearrange his schedule and fly out to rescue the sessions.

“Lars called me and said they were going nowhere and they were getting fed up with it and asked if I was available just in case,” says Rasmussen. “I told him I had a lot of gigs booked and if he needed me there I should know pretty fast… I got called up next day and he said come on over. Like, ‘When can you be here?’”

Arriving at One On One two weeks later, Rasmussen insisted the band start from scratch, keeping the rough cover versions, which could later be used as B-sides for singles, and just two of the drum tracks Clink had recorded with them, for the tracks Harvester Of Sorrow and The Shortest Straw. Flemming thinks it didn’t work with Clink because he “probably expected them to be more of a band-band where everybody played at the same time and you kind of took it from there. And they were nowhere near that at that time…

“They were fucking around with guitar sounds and had been so for like two or three weeks, and James was really unpleased,” he laughs. “When I spoke to Lars, he said, ‘We’re not gonna do another Master. It’s gonna be more in your face. It’s gonna be as pumped and as upfront as possible’.”

The end result was – as Lars had ordered – the hardest-sounding Metallica album yet, titled …And Justice For All, after the final line from the US Declaration of Independence, used here as shock-horror metaphor for the more general theme of anger at injustice that permeates every track. The trouble was that angry noise appeared to be all there was to most of it, to the point of deadening the emotions it was trying so hard to evoke; a roomful of mirrors in which all the reflections are hideously distorted.

Indeed, the whole thing sounded strangely flat, the drums, busy but tinny, the guitars, revved-up but muted, the vocals almost uniformly shouted and aggressive. If this was Metallica becoming more in-your-face, the effect was to push all but the most avid, hear-no-evil fan away – as unlovely a creation as anything Dr Frankenstein had sewn and bolted together in his laboratory.

It was hard not to conclude that for the first time, Metallica was not playing by instinct but doing something it thought it should. Slayer’s 1986 Rick Rubin-produced Reign In Blood had stolen the thrash crown, and Guns N’ Roses were now threatening to beat them to the punch when it came to subverting more mainstream rock tastes and Metallica were playing catch-up. With only Lars’ dreams and James’ nightmares to guide them, Cliff’s influence on Metallica would from this moment on be felt most powerfully by his absence. And, to begin with, they were utterly lost.

Writing about “mental anguish is what I like,” James would boast. “Physical pain is nothing compared to mental scarring – that shit sticks with you forever. People dying in your life always makes you think.” Had Cliff’s death become one of those things he’d thought about too much?

The first Metallica album clearly built for CD – with a total running time of over 65 minutes – the track sequencing still followed the same template as Ride and Master, beginning with a rallying-call opener, in this case Blackened, a howl of rage against the destruction of the environment, that was musically very much in the mould of Master opener Battery, and the only track on the album on which Newsted got a co-credit.

From there it was on to the self-consciously epic title track. Built around a quirky drum tattoo and the sound of marching guitars, James railing against how ‘Justice is lost/Justice is raped/Justice is gone…’ At almost 10 minutes long, Justice digs its own grave and buries itself, eliciting a huge sigh of relief from the listener when it finally – finally – slams to a halt. It’s not that it’s such a bad Metallica track – it would have shone more on Ride, perhaps, where the band was still establishing its credentials, and Hammett’s guitars, for which he receives the first of his three co-writing credits, are exemplary.

It’s just that the whole endeavour is so earnest, bitter, unrelenting, the unhappy sound of one man and his pain. Similarly, the samey-sounding tribute-to-Cliff instrumental To Live Is To Die, a sincere gesture rendered almost meaningless by the fact it’s the longest track on an album choked with tracks that outstayed their welcome.

The rest of the album – with one notable exception – continued along the same dark, tangled path. Again, it’s not that tracks like The Shortest Straw or The Frayed Ends Of Sanity are outright bad – both typically brutish rockers that would have taken pride on either of the first two Metallica albums – but after the sophisticated production and arrangements on Master and the warm, all-inclusive atmosphere of Garage Days, more was now expected of Metallica. Right at the moment they should have been delivering another sonic milestone, they had reverted to boorish type. Only what would have sounded scoldingly new four years before now sounded lumpen and off the pace.

Even the first single from the album, Harvester Of Sorrow, was horribly plodding. “Lyrically, this song is about someone who leads a very normal life, has a wife and three kids, and all of a sudden one day he just snaps and starts killing the people around him,” Lars explained at the time. If only the music had sounded even half as interesting. Still, it reached No.20 in the UK chart thanks to the by-now-huge Metallica fan base and the variety of formats Phonogram were now able to market the record in.

The track fed next to US radio, but not physically released as a single, was Eye Of The Beholder. Coming straight after the title track on the album, it sounded simply like more of the same, its saving grace on radio that its faded-in staccato rhythm was attention-grabbing enough to sustain the listener through the first couple of minutes before its droning repetitiveness finally zeroed you out. ‘Do you see what I see,’ James intones solemnly, ‘truth is an offence…’ And nobody, it seemed, had dared tell the band the truth about their new album.

The exception to all this – the one gleaming diamond in the dirt – was the track One. This was Metallica’s most ambitious and successful musical experiment yet, and their most deeply affecting song. The macabre story of an infantryman who steps on a landmine and wakes to gradually discover he has lost everything – his arms and legs, his five senses – except his mind, which is now cast adrift, trapped in its own grim and impossible reality, One was both nightmare writ large and musically transcendent journey, a thrash metal Tommy in miniature. The protagonist’s descent into living hell, wordlessly begging for death – capable of being seen both as existential metaphor for the human condition and the solipsism of the rock star life – its frantic climax also served up a state of inarticulate teenage angst like no other rock song before or since.

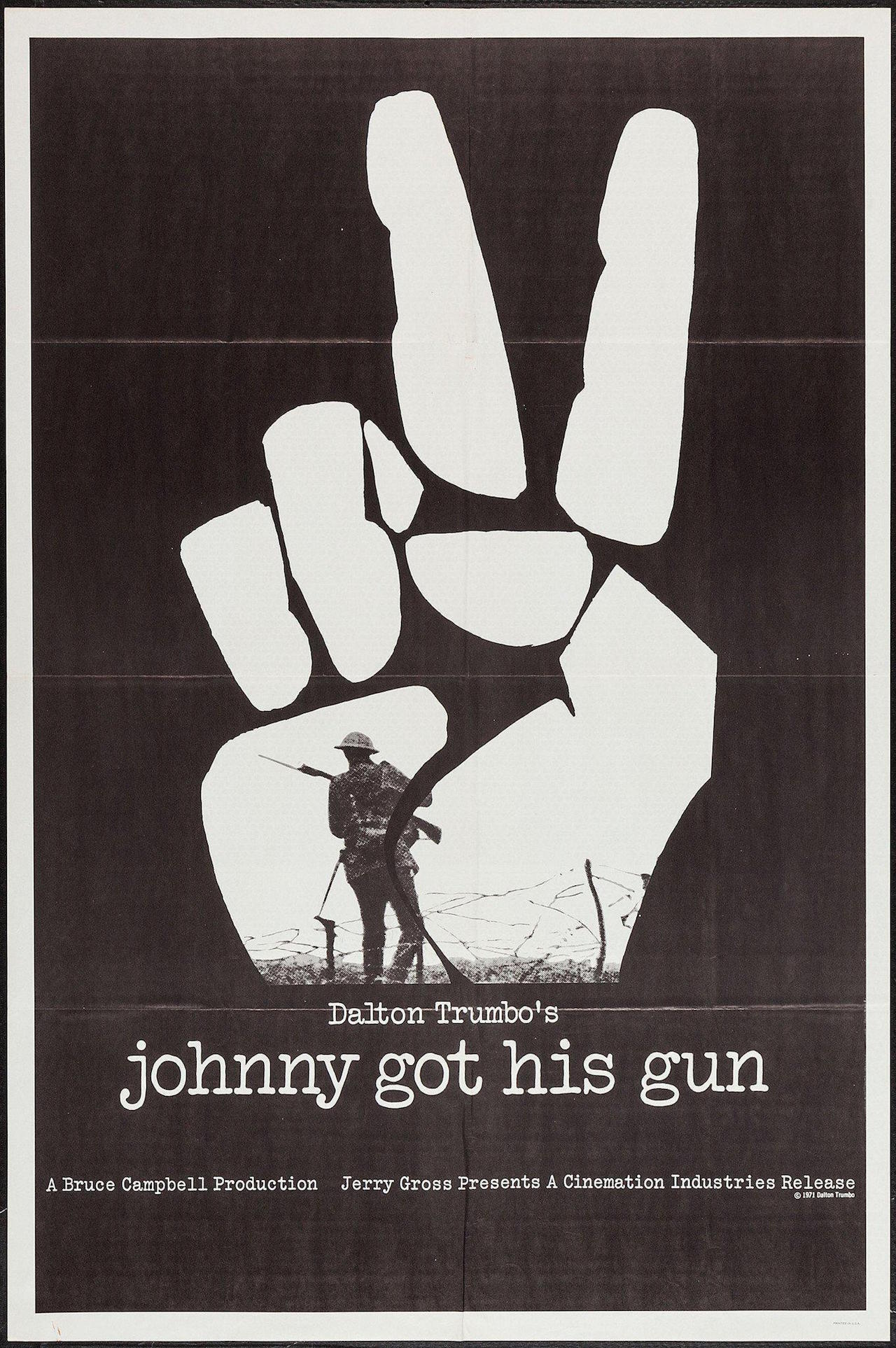

Partially based on the 1939 Dalton Trumbo novel, Johnny Got His Gun, One had started as a song James was thinking about based on the notion of “just being a brain and nothing else” before Cliff Burnstein suggested he read Trumbo’s book. The story of Joe Bonham, a good-looking, all-American boy encouraged to fight in World War I by his patriotic father, Bonham loses his legs, eyes, ears, mouth and nose to a German shell. After coming to terms with his gruesome circumstances in hospital while surrounded by frankly horrified doctors and nurses, Bonham uses the only part of his physical being he is still able to control – his head – to tap out a message in Morse code: “Please kill me.” “James got a lot of input from that,” said Lars.

There was another important change to their strategy they’d decided on before going into the studio: unlike Master Of Puppets, there would be at least one recognisable single and – even more significantly – video on the next album. Despite their public posturing, ‘refusing’ to release singles, both James and Lars had come around to the idea of a regular Metallica single and video since the unexpected success that year of Garage Days and, in particular, the homemade Cliff ’Em All video.

That One might lend itself well for some sort of visual interpretation that would complement the music in an arresting, artistic way, was obvious from the start. They became even more excited by the idea when it emerged that Trumbo – a left-wing, pro-peace screenwriter hounded out of Hollywood during the McCarthy-era witch hunts of the fifties – had actually directed a film version of the book, released in 1971 at the height of the Vietnam War. Might they be able to utilise scenes from it for a possible future video?

According to Rasmussen, they had actually bought the rights to the movie “in order to use it in the video” before they had even begun recording with him. “It was not much of a movie but they liked the look of it and thought it would look great in a video.” They also utilised some of the special effects on the original soundtrack, layering the sound of machine gun fire and exploding landmines over the intro to the track.

As Stairway To Heaven became for Led Zeppelin, One for Metallica represented the band at its musical apotheosis, containing all that was great and original about them in one long, incident-filled journey. From its quietly lush, heartrendingly melodic guitar intro to its steadily building mid-section, up to its volcanic, lights-out climax, its lyrics came straight to the terrifying point: ‘Hold my breath as I wish for death… Now the world is gone/I’m just one…’

This was not the standard rock stance of a Van Halen or Mötley Crüe, or even a Guns N’ Roses. This was revelation, a song utterly removed from its time and it’s unforeseen side-effect was to alter the circumstances surrounding Metallica forever. You didn’t have to be a Metallica fan to appreciate the artistry of One, anymore than you have to be a Zeppelin fan to adore Stairway. But if you were it was a milestone moment, one the band would arguably never equal.

Tellingly, the only other track after One that truly manages to transcend its laboured surrounds is the album’s shortest, Dyer’s Eve, its speedy razor-cut riff a moment of breathe-out relief after the tortuous slabs of prog-metal that precede it. The final track on the album, its success a mark of how heavy-handed the rest of the album sounds next to it.

It was also, interestingly, the first Hetfield lyric – ‘Dear Mother/Dear Father/What is this hell you have put me through?’ – in which the singer directly addresses some of the issues he carried from his repressed childhood.

“It’s basically about this kid who’s been hidden from the real world by his parents the whole time he was growing up, and now that he’s in the real world he can’t cope with it and is contemplating suicide,” Lars explained. “It’s basically a letter from the kid to his parents, asking them why they didn’t expose him to the real world…”

It was an ominous foreshadow of the type of material James Hetfield would explore in deeper, more ghastly detail on the albums to come.

Ultimately, instead of being the radically different masterpiece Lars had envisaged, Justice was a sideways step at best – a miscalculation. At worst, it was a disfiguringly weird statement the band would all largely disown as time went by and better albums were made. Its only real saving grace, the extraordinary One – and the fact it united them in never wanting to make an album so bleak in its outlook or dire in its musical palate again. The days of Metallica the out-and-out heavy metal monster were now numbered.

The other mystifyingly weird thing about Justice was the production. As Rasmussen says, “The sound was totally dry… Thin and hard and loud.” In fact, the whole album seems curiously void of reverb, the special sauce used to make the most mediocre sound sparkle in a mix. Rasmussen doesn’t disagree but maintains he delivered “almost ninety-nine per cent” of the sound he was instructed to get.

“Everybody was really pleased with it once we’d finished and then about a month or so after people were starting not to be so pleased. But over the time it’s probably the album that’s influenced most metal bands ever.”

Maybe so. Certainly David Ellefson of Megadeth wouldn’t disagree. “Because it was so progressive, it was complicated. In the early days we all prided ourselves on how fast we played. Then there came a point where we prided ourselves on how complicated we could be. Musical intellectual pride or some bullshit, you know?” He laughs. “If there was just some bass in here this thing would be fuckin’ heavy, you know? Really heavy…”

As Ellefson suggests, the most glaring omission from the sound on …And Justice For All was any evidence of Jason Newsted’s bass, an unforgivable omission given that this was his first album with Metallica, and their first without Cliff Burton.

Over the years there have been a variety of reasons given for this, from the accusation that Lars and James simply turned the sound of Jason’s bass down in the mix as another part of his hazing, to the suggestion that technically they simply didn’t leave enough room in there to hear Jason’s bass between James’ staccato rhythm guitar and Lars’ booming bass drum.

“I was so in the dirt,” said Newsted, speaking more than ten years later. “I was so disappointed when I heard the final mix. I basically blocked it out, like people do with shit. We were firing on all cylinders, and shit was happening. I was just rolling with it and going forward. What was I gonna do, say we gotta go remix it?”

There were, he said, “still weird feelings going on… the first time we’d been in the studio for a real Metallica album, and Cliff’s not there.”

Working alone with assistant engineer Toby Wright, he had used the same bass set-up as he would for a gig. “There was no time taken about ‘you place this microphone here, and this one sounds better than that… should you use a pick, should you use your fingers?’ Any of the things that I know now.” Recording three or four songs in a day, “basically doubling James’ guitar parts,” he was in the studio alone for less than a week during the whole three month period the rest of the band were working with Rasmussen. “Usually nowadays I’d take a day per song. That’s what I do on albums… But back then I didn’t even know anything about that shit. Just played it and that was that, right?”

Mike Clink says the lack of bass was an issue even when he was working with them. “They weren’t leaving enough room… sonically, to fit the bass in. But that was their concept and I think that if Cliff had been there it might have been a bit different. But with the new member, I felt he didn’t have as much to say. I think he was just happy to be there, at that moment. I think Jason just said, ‘This is the way it is, let’s roll with it’.” He adds, “It’s also the sound of the guitar. It takes up a lot of room in the sonic spectrum. But ultimately that was the decision of the band and the mixer.”

Rasmussen makes the same point about the mix. “I know for a fact, since I recorded it, that there’s brilliant bass playing on that album.”

Like Clink, however, Flemming was not responsible for the mix. That task fell to the production team of Mike Thompson and Steven Barbiero, whose previous credits included Whitney Houston, Madonna, the Stones, Prince, Cinderella, Tesla – and Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite For Destruction.

Mixing took place during May 1988, at Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, where James and Lars sat perched over Thompson and Barbiero’s shoulders. Interviewed at the time by Music & Sound Output magazine, Lars’ and James’ comments certainly back up Clink’s and Rasmussen’s claims that they – and not the producers – were the real architects behind the sound on Justice.

Asked how it differed from Master, Hetfield said: “Drier… Everything’s way up front and there’s not a lot of ’verb or echo. We really went out of our way to make sure that what we put on the tape was what we wanted, so the mixing procedure would be as easy as possible.”

Both men complained they didn’t want it to be like Ride The Lightning where “Flemming was in a reverb daze.” More tellingly, asked what they had learned from the “upfront and raw” sound of the Garage Days EP, Lars specifically mentioned “that mix,” with James elaborating: “We learned that the bass is too loud.”

“And when is the bass too loud?” Lars chirped in.

“When you can hear it!” they answered together, laughing.

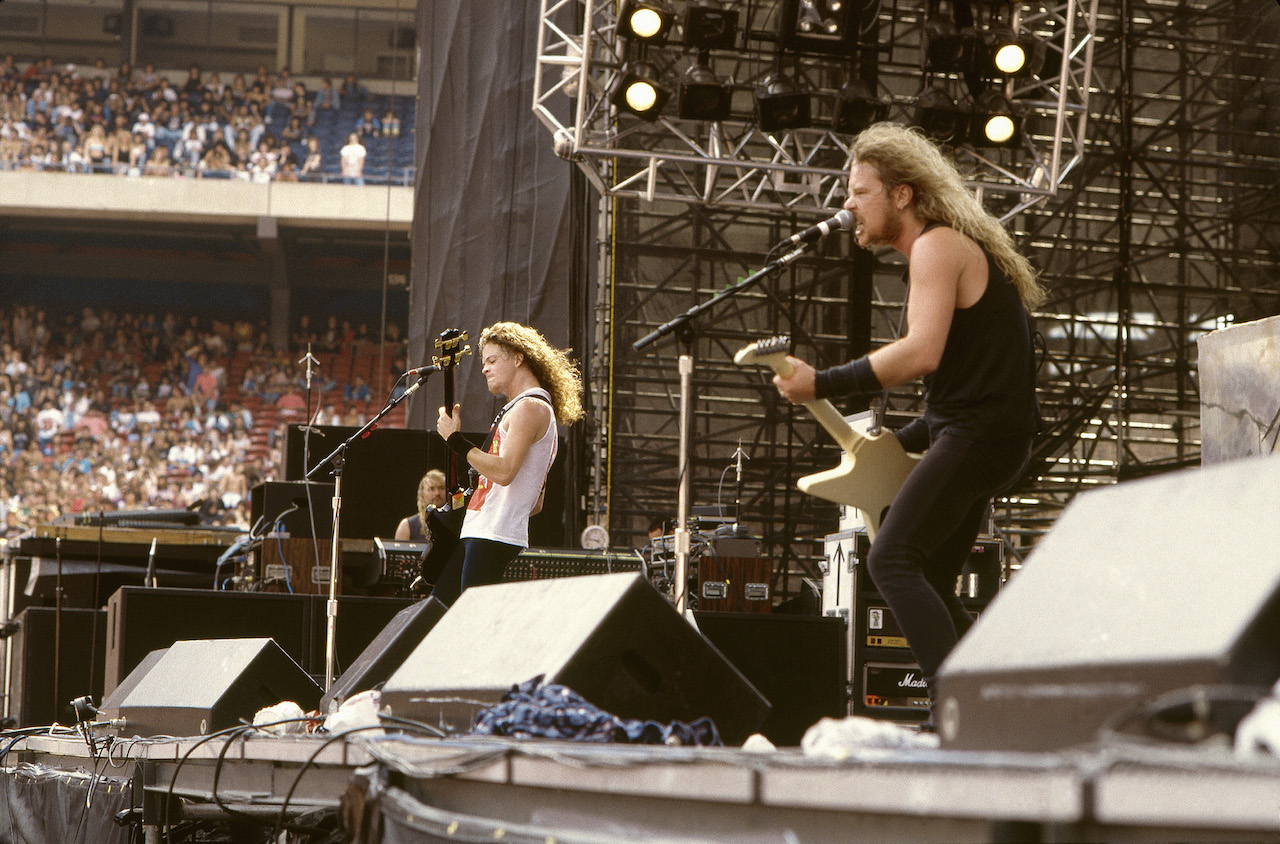

Whatever the truth, by the time mixing had begun in Woodstock, Metallica were already back out on the road, on the US version of the Monsters Of Rock festival: 25 dates at the biggest outdoor stadia in America, performing to upwards of 90,000 people a night; fourth on the bill below headliners Van Halen, the Scorpions and Dokken.

I travelled with the band for the opening two dates of the tour in Florida, at the Miami Orangebowl and the Tampa Stadium. “This has got to be the easiest trip we’ve ever done,” Lars laughingly told me. You could see what he meant. Although Metallica was on in the middle of the afternoon, they were the hot ‘breakout’ band of the tour and audiences were uniformly ecstatic. With just a 40-minute set to perform, the band also had an unusual amount of free time to fill. “I’ve been drinking since I woke up this morning,” James announced with a belch before they went on stage in Tampa, at the start of the tour.

There was now a small band of what they called their “tough tarts” at every show – girls waiting naked in the showers, girls in bikinis they’d given passes to the night before whose names they could no longer remember, girlfriends of boy fans offered to the band almost ritualistically.

“I couldn’t figure out why all of a sudden I was handsome,” said Kirk. “No one had ever treated me like that before in my life.” Both Kirk and Lars were starting to use cocaine more regularly too. Lars primarily, he said, because “it gave me another couple of hours drinking”, Kirk because it brought him out of his shell. And because he liked being out of his head, sitting there stoned gazing at horror movies, some on TV, some just playing out in front of him in real time in his hotel room.

The biggest drinker was still James, who would regularly polish off half a bottle of 70-proof Jägermeister. He was also into the vodka, though his brand had improved: he now favoured Absolut. “That whole tour was a big fog for me,” James later recalled. “It was bad coming back to some of those towns later, because there were a lot of dads and moms and husbands and boyfriends looking for me. Not good. People were hating me and I didn’t know why…”

He admitted that it wasn’t funny though when he got so drunk he became violent. “There’d be the happy stage. Then it would get ugly where the world is fucked and fuck you. I became… the clown, then the punk anarchist after that, wanting to smash everything and hurt people. I’d get into fights – sometimes with Lars. That’s how resentments would get released, pushing and shoving, throwing things at him… He wants to be the centre of attention all the time and that bothers me because I’m the same way. He’s out there charming people, and I’ll be intimidating so people will respect me that way.”

Meanwhile, the band’s reputation continued to grow with every appearance they made on the tour. When it became known that the Metallica T-shirt was selling more than any other bar the official event Tee, even headliners Van Halen began to take notice, singer Sammy Hagar making a big deal of coming over and spending “face time” with them both nights I was there.

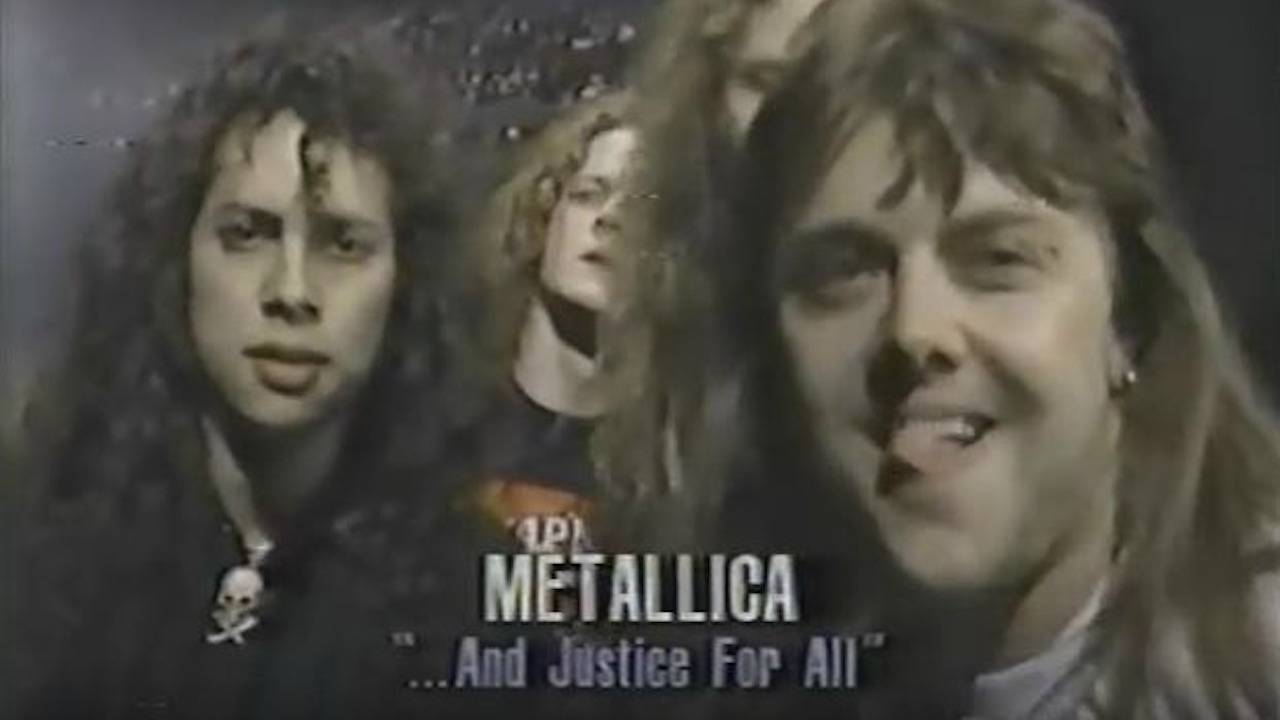

…And Justice for All was finally released on September 5, just as Master Of Puppets was officially certified platinum. Master had taken 18 months to sell its first million copies in America – Justice would take just nine weeks, peaking at No.6, their highest US chart position yet. Reviews were uniformly positive in Britain where the album hit No.4. At record company level, though, there were serious concerns. Dave Thorne, the band’s A&R man at Phonogram, spent his time defending it to “large numbers of opinionated people in the record company [who] were coming knocking on my door going: ‘This record sounds shit, what’s the matter with it?’”

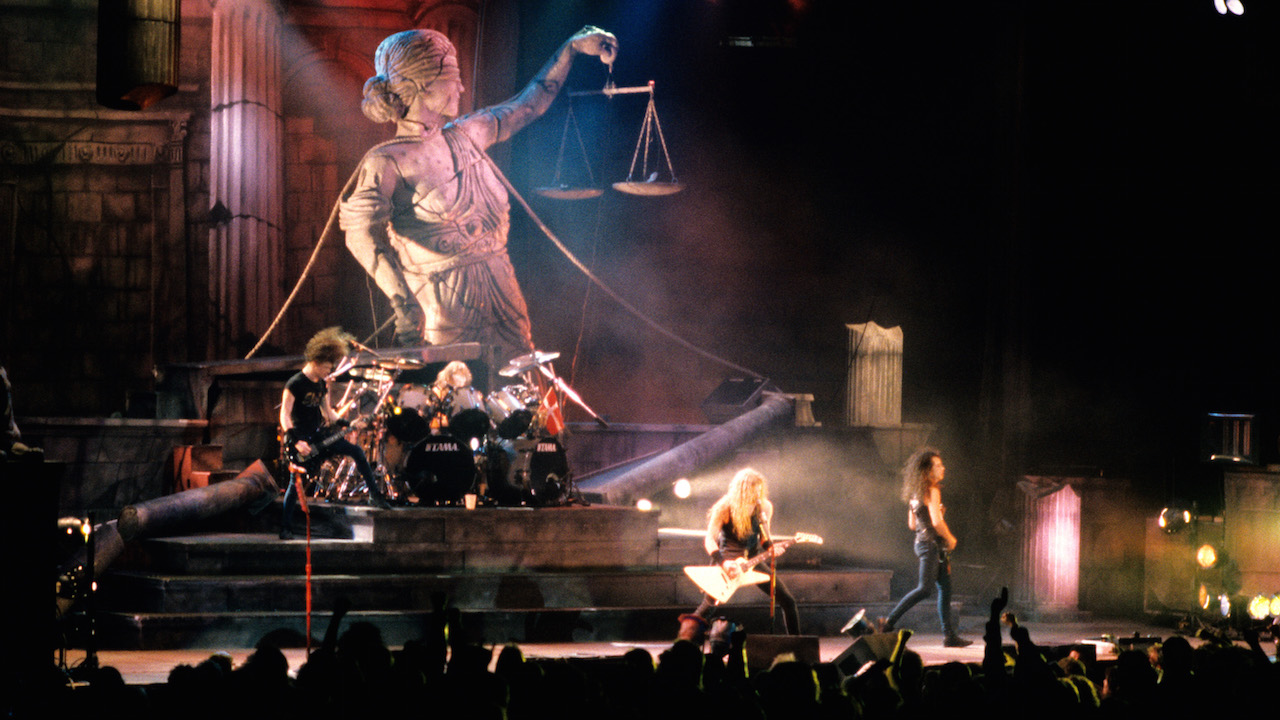

Nevertheless, the British and European legs of the Damaged Justice tour, as it was named, were a sell-out. The tour reached Britain in October, where they sold-out three nights at the Hammersmith Odeon. The big surprise of the tour was the band’s new stage show, their first attempt at anything elaborate, featuring a 20-foot replica of the album sleeve’s blindfolded and bound Statue Of Liberty – nicknamed Edna, after Iron Maiden’s Eddie – which collapsed melodramatically at the endless climax to …And Justice For All each night, its head falling off as if guillotined.

This was the era of the heavy metal pantomime as acceptable stage spectacle – led by Maiden’s ubiquitous Eddie figure, now brought to life for the encores each night, and Dio’s even sillier dragon (nicknamed Denzel) which singer Ronnie James Dio would ‘do battle’ with onstage – and in this context Edna’s plummet to disgrace every night was almost dignified by comparison. Nevertheless, it could have its comic, Spinal Tap moments too, like the nights when the statue simply refused to collapse or just its head would roll off the stage into the audience, or half an arm would fall off, swaying gently before toppling onto the drum riser.

What really put the album over the top, though, was the success of One when it was released as a single in February 1989.

Filmed in a disused warehouse in Long Beach the video for One was a stunningly accomplished piece of work. Built around actual footage from the movie version of Johnny’s Got A Gun, starring Jason Robards, intercut with stark, strobe-lit shots of the band performing the song, the One video would do for Metallica what none of their records or live performances, with or without Cliff, had yet been able to: both enhance their reputation as musical innovators and reposition the band centrally as mainstream rock stars.

The full, unedited video was nearly eight minutes long. Like the single, however, it was also made available to TV in edited form, minus the film footage, with a fade on the final couple of minutes of music. Even then it was so at odds with prevailing trends in 80s’ rock video, one MTV executive told their co-manager Cliff Burnstein the only place One would be seen was on the news. In fact, the full One video was premiered on MTV on the night of 22 January, 1989, on that week’s edition of Headbanger’s Ball. It instantly became the No.1 most requested video on MTV.

By February, One had became the first Metallica single to reach the US Top 40, peaking at No.35, while in the UK it reached No.13. One also achieved another landmark for Metallica when it attracted the attention of that year’s Grammy academicians, the band becoming shortlisted for the newly created award of Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance Vocal Or Instrumental.

“One proved to us that things we thought of as evil aren’t as evil as we thought,” said Lars, “as long as we do it our way.”

The Grammys show took place at the Shrine Auditorium in LA on 22 February, where the band was invited to perform their much-discussed new song. It was a momentous occasion, the first time an unashamedly ‘heavy metal’ band had actually played live at the Grammys – even though it was the truncated, five-minute version of the song.

Shrouded in shadows, colours muted so that they looked almost black-and-white, it was a stupendous performance from a band that Kirk later admitted was “very nervous” playing for all the suits and ties. “We were like diplomats or representatives for this genre of music.” There was a sense of outrage, however, when the band missed out on the award itself, that honour inexplicably going to Jethro Tull for their Crest Of A Knave album – a decision so unexpected that none of Jethro Tull was there to accept it.

Metallica put a brave face on it, like the whole thing was beneath them – they even suggested adding a sticker to the Justice album with the words: Grammy Award Losers. But privately Lars was seething. “Let’s face it, they really fucked up,” he told me. “Jethro Tull best heavy metal band? I mean, fucking come on!”

I caught up with the band again during their five-date tour of Japan in May, where I saw them play two shows at the Yoyogi Oylimpic Pool arena in Tokyo. They had been on the road for the best part of a year by that point but apart from James’s stomach problems, which he appeared to be trying to alleviate by downing as much Sapporo beer and hot flasks of sake as he could, they seemed to be holding up well and in generally good spirits. Money had come in and they no longer lived together as one, but they still went out together as a gang – when they were on the road at least.

Late at night they went to the Lexington Queen, a well-known hangout for rock bands since the days of Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, where it was said you could get a free drink just by mentioning guitarist Ritchie Blackmore’s name.

I sat with the band having a meal, and listened as they talked about the new houses they had all recently purchased, or were in the process of procuring, on the solid advice of their accountants, ready for their return home as millionaires for the first time later that year.

They were still new enough to wealth though to feign indifference, Lars protesting that he still drove around in “a piece of shit Honda”, James in a truck. Yet all I saw them in were limos and the private jet they travelled in while on tour in America – the same one previously used by Bon Jovi and before them Def Leppard. “We put some money back into how we travel while we’re on the road,” said Lars, “because we’re out there a long time and it just makes the whole thing easier.”

The more he went on, though, the more the others sniggered and made faces. “How about that house you just bought?” teased Kirk. “Where is it, like on a mountain?”

Lars looked at him, like ‘shut the fuck up’. It turned out the house he’d bought was situated so high on a hill he was considering having an elevator built just so people could get to his front door.

“Do it,” I said. “If you can afford it, why the hell not?”

“Yeah,” he said. “You’re right. I will…”

And he did.

Published in Classic Rock #252