April 6, 1974. In the warmth of an early evening in California, with the sun still shining, the four members of Black Sabbath looked out at the biggest audience they had ever seen.

300,000 people were massed at the Ontario Motor Speedway racetrack, 35 miles from Los Angeles, to witness the first California Jam festival, co-headlined by Deep Purple and ELP.

On the huge stage, beneath the arc of a steel-and-glass rainbow, Sabbath rolled out the heavy-hitting songs that had sold them millions of albums: War Pigs, Children Of The Grave, Paranoid.

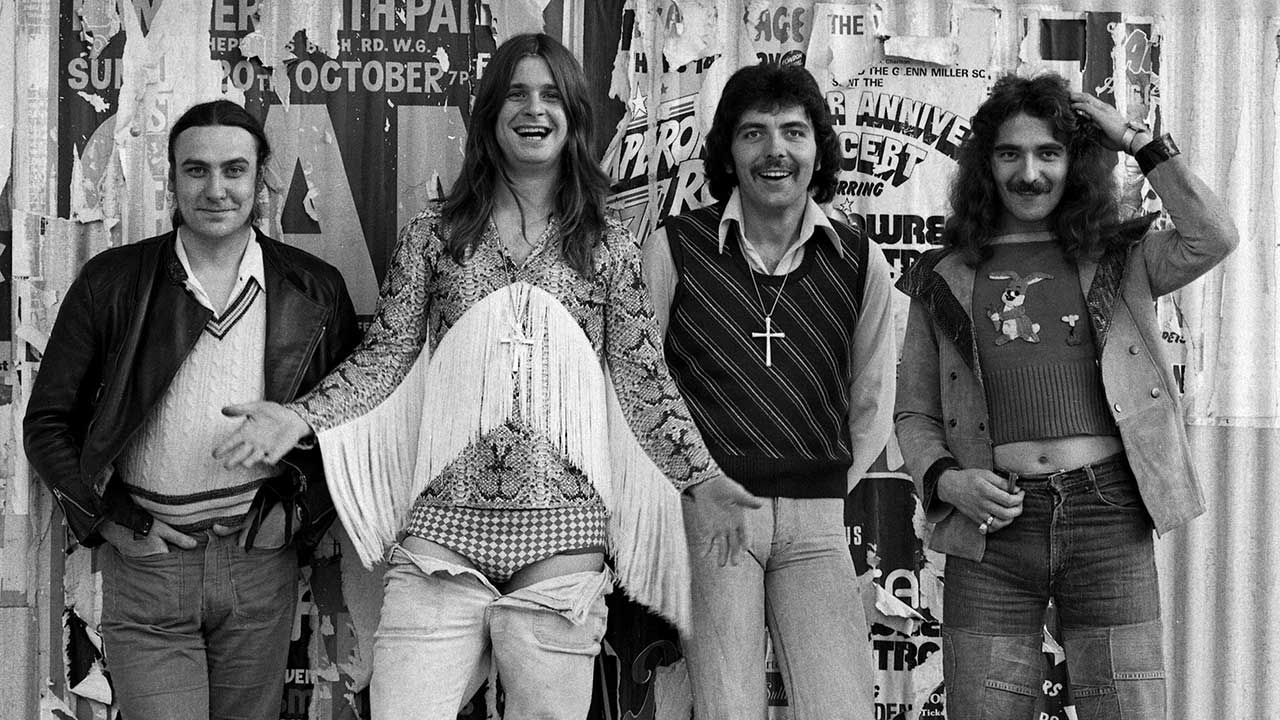

Apart from the bare-chested Ward, the band favoured the flamboyant couture of the moneyed rock’n’roll star: singer Ozzy Osbourne in purple-tasselled white jacket and outsized moonboots, bassist Geezer Butler in silver satin, guitarist Tony Iommi (minus his trademark moustache) in blue silk fringed with white.

Ozzy even spoke with a faux-American accent as he exhorted the crowd: “Let’s have a party!”

But after the high of California Jam, Black Sabbath would come crashing down to earth. According to Geezer Butler: “We hadn’t stopped touring and recording for five years. We needed to go home and become normal for a few weeks.”

But in the months that followed, Black Sabbath would face a far greater problem than mere fatigue. The band had decided to fire their manager. What resulted was a protracted legal battle, a bitter struggle that threatened to derail their career. It was a period that Butler describes as “total chaos”.

But out of this chaos would come one of the greatest and most influential albums in rock history, and the last classic album Sabbath would make with Ozzy. Its title – a bleakly humorous comment on the forces bearing down on the band – was Sabotage.

It was in 1970 that Patrick Meehan was appointed manager of Black Sabbath. The band had already made significant progress by this point, under the guidance of their first manager, Jim Simpson, a club promoter in Sabbath’s native Birmingham. Their first album, Black Sabbath, had reached the UK Top 10; their second, Paranoid, went to No.1. But as their popularity rapidly escalated, there was a feeling within the band that Simpson was a little out of his depth. In Osbourne’s opinion: “overwhelmed”.

Enter Meehan, a former assistant to the self-styled ‘Mr Big’ of rock’n’roll managers, Don Arden. The band were impressed by his global business plan, symbolised by his company’s name, Worldwide Artists, and by his go-getter attitude. “Meehan talked a good talk,” Iommi said. Once installed as Sabbath’s manager, Meehan delivered on his promises.

“In the early days,” Iommi said, “he really got things going. He was the one who got us to America.”

With Meehan at the helm, Black Sabbath became a genuine international success. The three albums that followed Paranoid – Master Of Reality in 1971, Vol.4 in 1972, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath in 1973 – all hit the UK Top 10 and the US Top 20. By 1974 the band had all the trappings of success, the country houses and flash cars.

But after four years on a continual cycle of touring and recording, they were running on empty. As Butler says: “We wanted to take a break after Tony collapsed with exhaustion on the Sabbath Bloody Sabbath tour. We were in England, having just returned from the tour, when our manament called us all and said we had to go back out to do the California Jam. We said no, but we were eventually forced into doing it.”

Moreover, Black Sabbath had grown suspicious of Meehan. Osbourne complained: “Patrick Meehan never gave you a straight answer when you asked him how much dough you were making.” Butler said, more bluntly: “We felt we were being ripped off.”

Shortly after their return from California Jam, the band notified Meehan of their decision to end their contract with Worldwide Artists. But Meehan was not going to give up one of the biggest rock bands in the world without a fight.

Such was the managerial turmoil surrounding Black Sabbath that it took them almost a year to complete the recording of Sabotage. Geezer Butler sums up the band’s state of mind during this period in four words: “Concerned, tired, drunk, stoned.”

The album was recorded at Morgan Studios in Willesden, north-west London, a state-of-the-art facility where Sabbath had made their previous album, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. The band worked at Morgan for a total of four months, split into three-week sessions.

Mike Butcher had been the engineer on Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, and he was charged with producing Sabotage. Butcher recalls that the sessions ran to a loose schedule. “I’d arrive at two in the afternoon, but the band wouldn’t start showing up until four. And because Morgan had a bar, that’s where the guys would wait for the others to arrive. So most days, we’d start work at nine and go through till one or two the next morning.”

Many hours were idled away in that bar, where Butler spent one drunken evening playing darts with Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts. “We called the dartboard ‘Bill’s beard’,” Butler says, “because all the stuffing was coming out of it at the number 3 mark.”

The drinking continued in Morgan’s studio rooms 3 and 4. The band also had a plentiful supply of cocaine and marijuana: “Bags of the stuff,” says Mike Butcher. During the actual recording, however, it was work all the way. “When it came to laying track, my intake of anything mind-altering would diminish somewhat,” says Bill Ward, drily.

Butcher recalls there was only one occasion during the sessions when work was impeded by a band member’s penchant for self-medication. “Because everything was recorded live, the band always wanted Ozzy to sing along as they were tracking,” he says. “But this one time, Ozzy was passed out drunk on the sofa, well out of it.”

Tony Iommi – identified by Mike Butcher as Black Sabbath’s “unofficial leader” – has stated that Sabotage was in part a reaction to the complex style of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, on which the band had combined their signature heavy metal with elements of progressive rock, aided by Yes keyboard player Rick Wakeman and even an orchestra.

“We could’ve continued getting more technical,” Iommi said, “using orchestras and everything else. [But] we wanted to do a rock album.”

Iommi was also reacting, on a deeper level, to the ongoing litigation with Patrick Meehan. “We were in the studio one day and in court or meeting with lawyers the next,” the guitarist said. And his anger and anxiety fed into Sabotage. “The sound was a bit harder than Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,” Iommi explained. “My guitar sound was harder. That was brought on by all the aggravation we felt over all the business with management and lawyers.”

Certainly Iommi’s heavy riffing is the dominant tone on Sabotage, not least on the song chosen as the album’s opening track, Hole In The Sky, which begins with the hum of amplifiers set at maximum volume and a scream of “Attack!” The scream was an in-joke, delivered by Mike Butcher.

“Sabbath had a supporting act who had a manager who would stand behind them on stage shouting, ‘Attack! Attack!’” says the producer. “So that’s what I shouted from the control room through the Tannoy.”

Even heavier was Symptom Of The Universe, Sabotage’s most famous and influential song. Its bludgeoning, staccato riff would provide the template for Metallica and countless other metal bands, but it was more than a one-note head-banger. It ended in a funky coda, created by the band jamming while recording the track and subsequently overdubbed with acoustic guitar.

There were more left turns throughout the album. Iommi may have set out to make a more straightforward rock record, but Sabbath continued the experimentation they started on Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. And, ironically, it was Iommi who created the most bizarre and unorthodox song ever to feature on a Black Sabbath album: Supertzar.

More atmospheric even than the song that gave the band its name, Supertzar was a darkly dreamlike piece featuring the English Chamber Choir, and described by Ward as “a demonic chant”. Tubular bells, played by Ward, carried an echo of the 1973 movie chiller The Exorcist.

The only connection to conventional rock music was Iommi’s slow guitar riff, played like a death march. Ozzy had no part to play on Supertzar, but what he heard as he observed the song being recorded was, in his words, “a noise like God conducting the soundtrack to the end of the world”. Iommi said, with characteristic reserve, that “it sounded really different and really great”.

In stark contrast was Am I Going Insane (Radio), essentially a pop song written by Ozzy on a Moog synthesiser, which he played on the finished track. “Oz drove us all nuts with that Moog thing,” Ward recalls, “but the song was great. And in hindsight, it was kind of a precursor for his solo career. His personality was blooming on this song.”

The ‘Radio’ in the title was British rhyming slang: Radio Rental – mental. Ozzy’s lyrics were “definitely autobiographical”, Butler says.

Even better, and even more pointedly autobiographical, were Ozzy’s lyrics for the album’s heavyweight final track, in which he poured scorn on Black Sabbath’s tormentor, Patrick Meehan. ‘You bought and sold me with your lying words,’ Ozzy sang, before threatening a curse on his enemy. The song was named The Writ, a title that was suggested by Mike Butcher after Meehan’s lawyers arrived unannounced at Morgan Studios.

“Some guy walked in and said: ‘Black Sabbath?’” Butcher recalls. “And Tony said: ‘Yeah.’ The guy said:‘I have something for you,’ and gave him a writ.”

Adding to the threatening vibe of The Writ was a sinister intro mixing laughter and cries of anguish. The laughter was that of an Australian friend of Geezer’s. “He was a complete nutter,” the bassist says. “We invited him into the studio when he was visiting London.”

The cries were those of a baby, recorded on an unmarked cassette tape that Mike Butcher found lying on a console at Morgan. When he played it at half speed, the baby’s crying took on an eerie quality. “It was so weird,” he says, “that it worked perfectly for that track.” Butcher never found out whose tape it was.

For Ozzy, writing and singing the words to this song had a therapeutic effect. “A bit like seeing a shrink,” he said. “All the anger I felt towards Meehan came pouring out.”

And yet, for all the vitriol in The Writ there was a note of hope, and defiance, in its closing line: ‘Everything is gonna work out fine.’ And, in the short term at least, those words would ring true. Patrick Meehan would not break Black Sabbath. Ultimately, they would do that to themselves.

In the spring of 1975, e month after recording was finished in London, Mike Butcher flew to New York to oversee the mixing and mastering of Sabotage. And it was here that the producer added, at the end of The Writ, a 31-second snippet of music he had recorded without the band’s knowledge. “Microphones were plugged in all around the studio,” Butcher explains. “So one night, when Ozzy and Bill were messing around on the piano, I pushed the record button.”

What he’d captured was a joke song named Blow On The Jug. “This stupid fucking thing,” says Ward. “A drunken song that Ozzy and me would sing together in a van or on a plane. That’s me on piano, and Ozzy blowing on one of those brown cider jugs, playing it like a tuba.”

Ward insists he had no idea that Blow On The Jug would end up on the album. But for the outfit he wore in the album’s cover photo – black leather jacket and a pair of red tights – he has no one to blame but himself.

“I had this old pair of jeans that were really dirty,” he explains, “so I borrowed my wife’s tights. And so that my bollocks wouldn’t be showing under the tights, I also borrowed Ozzy’s underpants, because I had none.” Ozzy didn’t look much better, in traditional Japanese garb that led to him being mocked as “the homo in the kimono”. It spoke volumes about where the band’s heads were at. “Chaos personified,” Butler says bluntly.

Nevertheless, when Sabotage was released on June 27, 1975 it was well received. In the UK chart it peaked at No. 7, and although it made only No.28 in the US – a disappointment after four consecutive Top 20 albums – it was highly praised by Rolling Stone magazine. “Sabotage is not only Black Sabbath’s best record since Paranoid, it might be their best ever,” stated reviewer Billy Altman.

Altman noted “the usual themes of death, destruction and mental illness running throughout this album”. But Geezer Butler, Black Sabbath’s principal lyricist, didn’t limit himself on Sabotage. In Symptom Of The Universe he addressed the meaning of life.

“The title was about love, fate and belief,” he explains. “Love is the symptom that brings forth life. Death is the cure, but love never dies. I was very religious growing up, and everything in my life seemed to be pre-planned.”

Theology was also at the heart of Megalomania, a nightmare vision of drug-induced madness. “It was based on a rare heroin experience I had,” Butler says. “I stayed up all night looking in the mirror: I was God, and my reflection was the Devil. It was the battle of the two biggest egos in the universe. Unfortunately I don’t remember the outcome.”

Butler freely admits that much of his writing for Sabotage was done while stoned out of his mind. But with the lyrics for Hole In The Sky he wrote with a prescience that would prove chillingly accurate.

“The most prophetic lyrics I have ever written,” he says. “The Western world going down in the East, a hole in the ozone layer, no future in cars. It seemed to me that everything east of Europe was becoming a threat. Japan was rising in the business world, Chairman Mao was building up China, the Soviet Union was threatening nuclear war, and the Middle East was in turmoil as usual. At the time, oil was on everyone’s minds and petrol was being rationed.”

With Hole In The Sky, Butler caught the mood of the times just as he had done five years earlier with Sabbath’s Vietnam-era protest song War Pigs. But, as he says now: “I usually tried to instil some hope into the bleaker images of my lyrics. Growing up in Aston, I’d had my share of violence and negativity. So I was a bit of a ‘peace and love, man’ bloke.”

And it was this sensibility, heightened by a shared fondness for smoking dope, which held Black Sabbath together through this troubled period.

“We were constantly stoned,” Butler says, “so we were never confrontational towards each other. It was an ‘us against them’ attitude in the band. We relied on each other – there was no one else we could trust.”

Bill Ward believes it was sheer force of will that got Black Sabbath through the making of Sabotage. “We’d taken some knocks,” he says, “but we carried on. It was a tough band.”

Butler remembers that “we were burned out by the time the album was finished.”

And by the end of 1975, Black Sabbath realised just how much they had lost in their battle with Patrick Meehan. “We had to pay him off to get out of our contract,” Butler says. “It cost us thousands of dollars of lawyers’ bills. And then we got a huge tax bill. The Inland Revenue didn’t sympathise with us. They blamed us for being naïve. Most of our money went to lawyers and taxes.”

Rid of Meehan, the members of Black Sabbath decided to manage the band’s affairs themselves. But common sense prevailed when they appointed Mark Forster to run the day-to-day business (ironically, Forster was a former employee of Patrick Meehan).

And Sabbath did carry on. In purely pragmatic terms, they had to. But after Sabotage they would never be the same again. The chaos that engulfed the band during the making of that album would have a profound effect on their lives. “It changed us,” Ward says. “I have no doubts about that.”

Without a designated manager to mediate between them, the band members – tired, pissed off, drug-addled and financially drained – began slowly to drift apart. “The band,” Butler reveals, “was disintegrating.”

In 1976 they hired Don Arden as their new manager, but there was little that Arden could do to save Black Sabbath. The band’s 1976 album Technical Ecstasy was the beginning of a steep decline, both creatively and commercially. Following 1979’s weak Never Say Die!, Sabbath fired Ozzy Osbourne. The news did not come as a shock: Ozzy had already quit the band twice in the years leading up to his sacking. The strain that had been building within the band ever since the making of Sabotage had finally reached breaking point.

Although this album carries memories that would sooner be forgotten by the men who created it, there is a greater aspect of its legacy. What Black Sabbath created while they had their backs to the wall was a masterpiece. Their first four albums hold mythic status as genre-defining classics. Sabotage, as fearlessly experimental as Sabbath Bloody Sabbath before it, added another dimension to Black Sabbath’s music. Its power still runs deep today.

“That album,” Bill Ward says, “it was so hard for us making it. But when I listen back to it now… God, it’s incredible.”