Dig, if you will, a picture. It’s the summer of 1970. In a tiny, sweltering, fourth-floor apartment in Manhattan, just around the corner from the Fillmore East, a teenage rock band from Florida, armed to the teeth with guns, grit, and guitars, sleeps seven to a room and dreams big dreams. Bass player Greg T. Walker was there. In fact, the whole thing was his idea.

“The third day we were staying there, someone broke into our van and took about half of our equipment,” he remembers.

“We still managed to get a few dates though, and we’d get paid $150 or $200, and we’d buy a sack of potatoes or some cereal. We’d eat one baloney sandwich a day. I remember one time putting water on Cheerios. This lasted through the following year. There were some very lean times. But we were young, we had a choice. We decided to stick it out.”

Nearly 40 years later, after eight albums, countless world tours, personal tragedies, and many millions of faces thoroughly rocked, Blackfoot is still proudly sticking it out.

The band began in late 1969 as Fresh Garbage and soon after as Hammer, a loud, gangly garage band fuelled by Spirit and the Zombies. Most of the band were childhood friends growing up together in Jacksonville, Florida. They were young and brash and played with unparalleled ferocity, which earned them an early, life-changing break.

“We were playing New Years’ Eve here in Gainesville,” says guitarist and founding member Charlie Hargrett, “and this girl here that we knew had gotten this job in Manhattan working at a production company in the Brill Building where Carole King and all those people were writing. So, she had a job up there and came home for the holidays and saw us. A couple weeks later we get a letter from New York. It says, ‘Hey, my boss wants a tape’, so we put a demo together and she said, ‘C’mon up, you can stay in my apartment’. So we did.”

Ergo, the watered-down Cheerios and the hard times. “We didn’t think we were paying dues, but we were,” he laughs. “We were broke.”

Several things happened in quick succession then. For one, most of the band got arrested for firearms possession. “We’re from Florida, man,” Greg shrugs. “When we first showed up in New York, we had guns on the dashboard of the car. We had no idea.”

Then the band found out there was another Hammer already in operation. “We needed a new name quick,” Charlie says.

“Since we were moving up north to start a big recording career, we thought, ok, we’ll call it ‘Free’, because we’re free now. And then All Right Now came out, and we were like, ‘Shit’. So Jakson came up with Blackfoot, because of his Native American heritage.”

Both drummer Jakson “Thunderfoot” Spires and Greg T. Walker were Native Americans, so the name seemed appropriate. It should be pointed out, however, that no one in the band is an actual Blackfoot Indian. “No, Jakson was Cheyenne, Cherokee, and French,” Greg says.

“He always said he got his creativity from the first two, and blamed his faults on the French. I’m Muskogee Creek. Nobody was Blackfoot, but it was a nice bold sounding name. Just that simple.”

With a new name and a working knowledge of the New York justice system, the band moved to the Jersey shore to plot their next move. And then they promptly broke up.

“This place we ended up in was a real shithole,” Charlie remembers.

“There wasn’t really a club scene up there either, so we were surviving by playing frat gigs and high schools. When that stuff closed up for the summer, we were out of work.”

Blackfoot frontman Rickey Medlocke was asked to drum for Lynyrd Skynyrd. He accepted, and left the band. Not soon after, Greg Walker joined Skynyrd as well. The remainder of the band ended up in North Carolina, where they joined up with a mysterious figure named Lenny Stadler, who had a band called Blackberry Smoke. But then Stadler got sick, found God, and denounced rock’n’roll. Weird days, those.

“They were. By that time Rickey was back in the band, and then Greg came back, too. We got back together and moved to New Jersey, our old stomping grounds. By then there was a club scene and there were places to play, and we could survive the year,” Charlie says.

“Rickey had some connections at Muscle Shoals studio in Alabama because of Skynrd, so we went down there and recorded an album on spec. They sold it to Island Records.”

In 1975, Blackfoot’s first album, the cleverly titled No Reservations, was released. Its cover was a conical, pop-art nightmare more suited for Kraftwerk than a no-nonsense southern heavy metal band. Not surprisingly, it sank like a stone.

“It had the ugliest cover you’ve ever seen,” Greg agrees.

“I believe it actually won an award for the guy who designed it. Then, in 1976, we switched to Epic records, and released Flying High. It did a little better, but not enough to make a difference nationally.”

“The Island record came out the same time as Bob Marley, and the Epic record came out the same time as Boston,” Charlie notes. “So we were buried, and both records became Frisbees.”

Still, despite their flagging recording career, the band continued to prove their mettle on stage.

“The first two records didn’t sell,” Charlie says, “But they got us going enough to be playing with other bands across the country.”

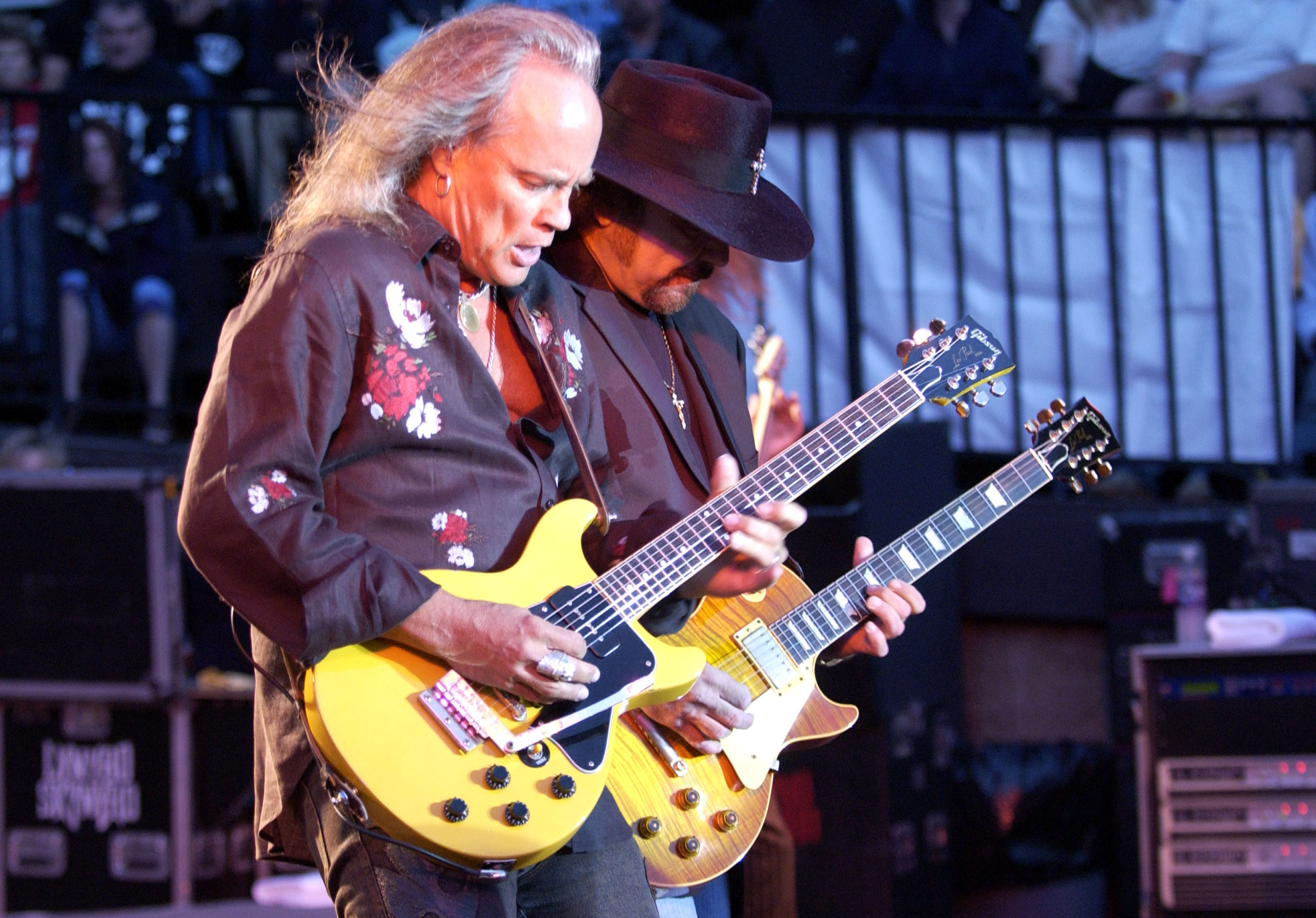

The band took the opportunity to hone their chops to a razor edge. Southern rock had exploded around the country, but none of them offered the sheer overkill of Blackfoot’s relentless twin-guitar attack. By the late 1970’s, Blackfoot became the most terrifying underachievers in rock’n’roll.

“Early on, we were opening for a lot of bands like Mountain, Rick Derringer, Edgar Winter, people like that,” Greg says.

“So we got a lot of exposure and a taste of playing on big stages, full-on concerts with 8-10,000 people every night.”

“We always played like we were the headliners,” Charlie adds.

Blackfoot’s big break finally came in 1978. The band was playing a string of southwestern dates with Brownsville Station when Brownsville’s frontman and perennial rock-booster Club Coda introduced them to his management company. They soon signed on with Atco Records and released Strikes in 1979. It was their first gold record, and the hustle was on.

“Strikes went gold real fast,” Greg says, “And people started saying, ‘I like this new band Blackfoot.’ They were calling us an overnight success and we were saying, ‘Yeah, right – a ten year overnight success!’”

The band spent the next five years on the road, taking breaks only to record new albums or brawl with their touring-mates.

“Oh right, Blue Oyster Cult,” Greg laughs.

“We just didn’t hit it off, and the first night of the tour – we had like 30 something dates booked – there was already friction. The second night was a little worse, and the third night, we came to blows. I didn’t even know what the problem was. We were just playing our hearts out, and maybe they resented it.”

The band toured with Kiss, BÖC, UFO, AC/DC, Black Oak Arkansas.

“In 1979, we were travelling in a van,” Greg says. “By 1980, and we had two buses, two tractor trailers, 22 guys on the crew. It just never stopped. We went 22 months without a break. But we didn’t really want one. We loved it.”

In 1983, Blackfoot released Siogo, their first album with former Uriah Heep keyboard player Ken Hensley. Despite the minor success of lead-off single Teenage Idol, the lighter, more commercial sound of the album turned off many long-time Blackfoot fans.

“At that point, the record company was saying, ‘We need another hit, you have to modernize the sound, get with the times’,” Greg says.

“I think it’s called ‘grabbing at straws’ now.”

The band managed to squeeze out one more album, 1984’s dismally-sellingVertical Smiles, before finally collapsing from exhaustion and record company pressure. Despite a pact to fully dissolve the band, Rickey Medlocke continued to use the Blackfoot name for another decade, although none of the other members were involved. Later on, he rejoined Lynyrd Skynyrd as a guitarist. Greg, Jakson, and Charlie all played with the Southern Rock All-Stars over the years, but Greg had always hoped the band would someday rise from the ashes. And in 2004, it did.

“I was out on the road with Pat Travers,” Greg remembers, “And I thought, Damn, I just want Blackfoot back. So I called Charlie, and I called Jak. Charlie called Ricky too, and he said he was happy with Skynrd, and that he didn’t want anything to do with it. But we had three of the four, and that felt good. I remember when we first got back together, we said, ‘As bad as we want this in our hearts, and as capable as we think we are, we have to face the facts – what if we get back together and we don’t have the same vibe? What if we don’t click?’ So we got together in New Orleans, and I swear, within eight seconds of the first song we played, I was beaming from ear to ear, It was like ‘Yes!’ Because I had Jakson back. We all looked up at each other and said ‘Yeah, this’ll work’.”

Blackfoot began playing shows again to resounding success, but in March of 2005, tragedy struck when Jakson Spires died suddenly of an aneurysm.

“It still hurts to this day, and will probably hurt for the rest of my life,” Greg says.

“We spent a lifetime together. He was truly a brother.”

Still, Greg and Charlie both feel Jakson would have wanted them to carry on.

“We had actually talked about this before we got the band back together,” Greg says. “We were trying to be smart and plan for the future. We brought up things, like, ‘What if somebody breaks an arm? What if you’re disabled permanently?’ And the answer from everybody was, ‘You keep going.’ So we had that peace of mind knowing that we had to continue. That was his wish, as it was mine.”

“I feel privileged to still be doing this,” Greg says.

“I mean that with all my heart. It’s who I am and what I am. It’s all of us.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #121.