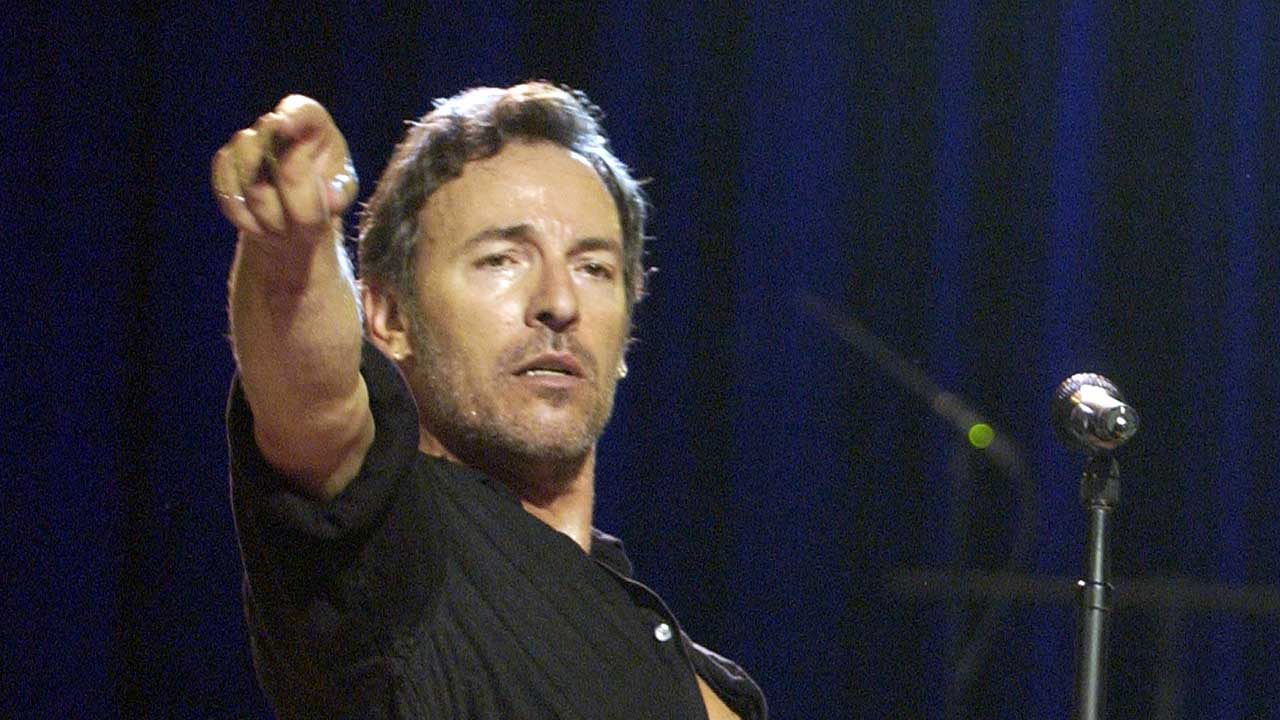

How Bruce Springsteen's The Rising helped America heal after 9/11

As America mourned in the wake of 9/11's terrorist attacks, Bruce Springsteen made The Rising, an album that offered comfort and light in the cruellest, most impenetrable darkness

Like countless millions of people around the world, Bruce Springsteen watched the dreadful events that unfolded on Tuesday, 11 September 2001 on his television. Ten days later, Springsteen took a call at his New Jersey farmhouse from his long-serving manager, Jon Landau. A telethon had been organised to raise money for the victims of the first terrorist attacks on mainland America and Springsteen had been asked to open the show.

He quickly wrote two songs, Into the Fire and You’re Missing, each of which explicitly referenced the event, both lyrically and in their downbeat mood. However, Springsteen, habitually a slow, prevaricating worker, didn’t feel either was complete enough yet to unveil in public. Landau suggested he perform instead a song he’d written a year earlier about the economic decline of his adopted hometown, Asbury Park, but which also fit the moment.

That was My City of Ruins, an urgent, pleading gospel track that drew its inspiration from Sam Cooke. Alongside those two more recent songs, it was the starting point for The Rising, the 12th and perhaps most affecting studio album of Springsteen’s career.

A second catalyst occurred right around the same time and as Springsteen was walking back from the beach one late-summer afternoon. A passing motorist happened to spot the local hero and, speeding by, shouted out from the open window of his car: “We need ya, man!”

“That made me sense, like, ‘Oh, I have a job to do,’ ” Springsteen told Rolling Stone in 2002. “Our band, hopefully, we were built to be there when the chips are down.”

Just then Springsteen was emerging from his own long, dark tunnel. Following the phenomenal success of the Born in the USA album, he’d broken up the E Street Band, the bedrock of his sound for more than a decade, gone through a painful divorce and suffered a sharp decline in his commercial fortunes with the Human Touch and Lucky Town albums of 1992.

His only record since then, 1995’s The Ghost of Tom Joad, cut almost solo, was hushed, haunted and marginalised him still further from the mainstream. Bloodied, in 1999 he’d revived the E Street Band for a tour that was triumphal, but through which he had the air of a fighter swinging from the ropes.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Rising, though, was a different matter altogether. In total, it was as if, as Springsteen noted, when his audience, and even his whole damn country, needed him the most, he was again able to stand tall. And by seeking to staunch America’s psychic wounds, he also made himself strong once more. It was not so much an album of great, impassioned rock’n’roll, though it was that too, as an act of healing, a re-affirmation of faith and a road out of the bleakest of times and towards a sort of redemption.

For the first time in 18 years, he had the E Street Band at his side to give heart, soul and heft to his songs, and crucially, a new producer. Brendan O’Brien had made his reputation working with, among others, Pearl Jam and Rage Against the Machine. He was a natural to harness the E Street Band’s elemental power and also give them a more contemporary feel.

It was no accident that The Rising was Springsteen’s freshest and most vibrant-sounding record since Born in the USA. Springsteen’s, Steve Van Zandt’s and Nils Lofgren’s guitars were here hard as diamonds; Max Weinberg’s drums like blows to the solar plexus.

Outside of such surface details, though, the crux of the record was its sense of purpose, its thematic coherence – several of its 15 songs were written pre-9/11, but none was not evocative of it – and the manner in which Springsteen chose to deal with such a raw, complex and so painfully recent happening. For while his President, George W. Bush, and America’s government were driven by a kind of crazed bloodlust, Springsteen sought instead to bring not just solace, but also to find a common ground with his country’s perceived enemies.

Nowhere was this more apparent than on the album’s centrepiece song, Worlds Apart, which explicitly featured the intense wailing sounds of Qawwali, the vocal music of the Sufi sect of Islam. Springsteen used this and a propulsive, turbulent, shape-shifting rhythm to extract, rather than inject poison. ‘In the beating of our hearts,’ he sang, voice bruised and cracking at the edges, ‘may the living let us in, before the dead tear us apart.’

Elsewhere, time and again, he used sombre blues, rustic folk and keening gospel as his musical palette, whilst his lyrics were littered with images of fire, smoke and darkness, loss and grief, but also love and tenderness. And at its end, with its surging, uplifting title track and the closing My City of Ruins, The Rising resoundingly offered the comfort that light could be found even in the cruellest, most impenetrable-seeming blackness. And almost evangelising, Springsteen brought the song and album to an end invoking the highest power. ‘With these hands, I pray for the strength Lord,’ he sang and then re-joined his listeners: ‘Come on, rise up. Come on, rise up.’

The mere fact that he should have been bold and big-hearted enough to want to put his country back on its feet remains his own very singular achievement.

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.