“Vilely I defile, chastise, humiliate/Writhing, agonised as I violate to impregnate/With lathering soaps and suds I slowly enemize/Innards gurgulate as they’re sickly baptised…” – Carcass, Excoriating Abdominal Emanation

“That was a rape song about a guy getting sodomised,” says Carcass bassist and vocalist Jeff Walker of his band’s infamous 1989 track. “Rather than a woman as a victim, it was a bloke for a change. It wasn’t a sexual rape, though – it was more of a violent enema. The point was to make people squirm.”

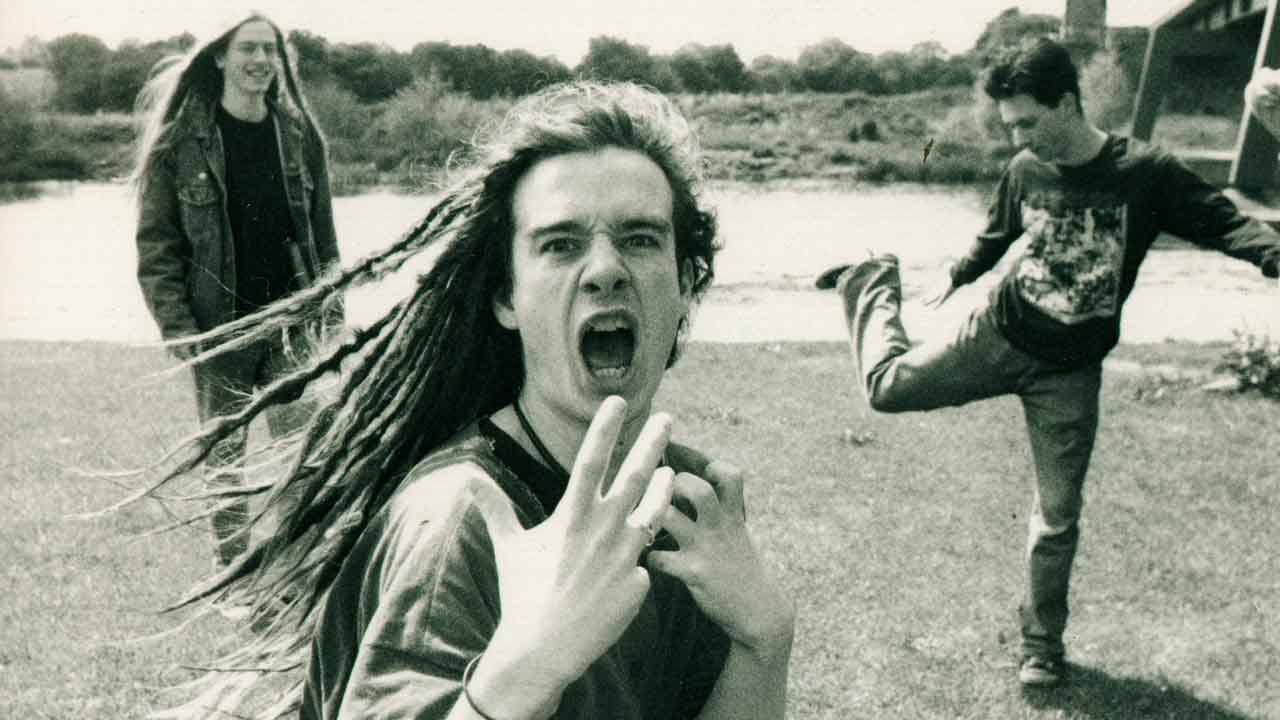

Excoriating Abdominal Emanation appeared on the Liverpool grindcore trio’s twisted second album, Symphonies Of Sickness. Back then, Jeff was 19-years-old with a mass of dreads.

“We were reacting to what we perceived as redneck, misogynistic, homophobic crap,” he says. “Which sounds pretty right on and PC, but that’s what we felt at the time. It seemed that metal had been taken over by a jock mentality.”

- Take a look at the best true wireless earbuds

- The best smart speakers: find the right voice-assisted speaker for you

- Best record players: turntables your vinyl collection deserves

- The best metal guitars 2020: Get ready to shred with our essential list

The first Carcass album was 88’s Reek Of Putrefaction. Recorded while guitarist Bill Steer was still in Napalm Death, it’s one of the most underground-sounding albums of all time… literally.

“It was spoilt by a really lazy engineer who couldn’t give a fuck any more,” alleges Walker. “It’s a shame, because there were some killer riffs on there, muddied by the production. But some people love it – they can imagine what the riffs sound like!”

It attracted the attention of iinfluential radio DJ John Peel, who took to playing the deliberately graphic and consciously provocative likes of Genital Grinder and Vomited Anal Tract on his eclectic show. The album’s cover didn’t go down so well with bigger record stores, though, as it presented a collage of real-life dead flesh. The lyrics made humorously grim reading, too, with their clinically detailed descriptions of the human anatomy’s least pleasant features and frailties.

“None of us had any real knowledge of that stuff,” chuckles Walker. “Ken’s dad was a vet, and my sister was a nurse with a medical dictionary. The rest was just our puerile imagination!”

While Birmingham had been the birthplace of Reek…, its follow-up would be laid to rest in a two-street East Yorkshire town. One of Driffield’s 10,000 inhabitants happened to be Colin Richardson, an in-house engineer at the aptly-named Slaughterhouse Studios. Richardson’s previous work on Discharge’s celebrated 1982 debut Hear Nothing, See Nothing, Say Nothing prompted Earache Records owner Digby Pearson to book him for the job of finally affording Carcass some sonic quality.

“Carcass told me that they couldn’t stand the sound of the first album,” recalls Richardson, who went on to work with Machine Head and Fear Factory, among many others, “because it sounded like they were in a cupboard with the mic outside. They wanted everything clear and up-front.”

Walker has vivid recollections of the Symphonies Of Sickness sessions, which would last a mere three weeks between July and August of 1989. “We’d borrowed the drums off Mick Harris from Napalm Death and used [Napalm bassist] Shane Embury’s bass gear. The studio was across the road from a nightclub where all these Garys and Sheilas would go. The window in our studio looked out at the club, so we’d be recording the album watching all these squaddies from the local Army base pick fights with farmers.”

“Driffield is about 15 years behind,” remembers Richardson. “Of course now, it’s full of kids wearing metal hoodies, but back then the attitude towards them was (a) we’ve never seen you before and (b) you’ve got long hair.”

Carcass would indeed draw funny looks whenever they nipped around the corner to grab some veggie burgers from the local chippie. While Slaughterhouse Studios incorporated a pub and a nightclub, booze was the last thing on their warped creative minds. “We were sober,” laughs Jeff. “I wasn’t drinking, for once in me life!”

Walker also remembers the band befriending a local metalhead who they bumped into in the street. “He’d hang out at Slaughterhouse and play us some old-school metal videos: stuff like Venom and Tank.”

Richardson recalls Carcass as being “quite shy, at first. Then – and it’s clichéd to say it – the dry Liverpool humour came out. I guess we hit it off because I’m from Manchester. Jeff was pretty sarcastic, but in a sweet way. Bill was quiet, but came out of his shell, and Ken was cool as well. Nice guys. There was no rock’n’roll going on, though – many cups of tea were drank!”

While Reek… had been recorded live, Walker credits Richardson for sharpening up their attitudes: “We had a bunch of riffs and lyrics and just wanted to record an album with a half-decent sound,” he says. “We were never ambitious: we just did stuff as we went along. We went in there and started recording it live and it didn’t work. Colin stopped the tape and said, ‘you can’t get away with this!’. He disciplined us to do it properly – we discovered the art of ‘drop-ins’ and layered guitar, bass and drums, etc. We realised we had to pull our fingers out.”

“It was a pretty normal session,” says Richardson, “but I do remember thinking what a genius Bill was on guitar. He would practise all the time, and that’s the difference between someone who just talks about it, and someone who really gets stuck in.”

Digby Pearson would often visit the studios – partly through the excitement of what was coming together and partly to keep an eye on his investment. Back then, the album’s £3,000 budget could make or break Earache, depending on the sales. The label’s centre of operations was Pearson’s Nottingham bedroom, and each release would fund the next. “I couldn’t believe I was getting the chance to release this album,” he says, “and couldn’t believe I was getting the chance to release it. They had their own style going on – pathological grind, medico grind… no-one had really come up with a name for it. The blanket name for bands like Carcass was grindcore, but they were the only band I knew of who were going off on this whole pathological medical horror thing.”

Carcass would continue to work with Colin Richardsand on successive albums, bigger budgets translating into better production with more clarity and depth. Yet Symphonies Of Sickness remains their most savage, gloriously unhinged work. Cranked up today, it will stand tall against any other extreme/death metal disc you’d care to spin. Besides being a rabid assault on the ear-holes, it’s chock-full of brilliantly inventive passages and deeply disturbed melodies – if no actual choruses.

“There are no choruses on the album,” notes Jeff, “because I thought it was lazy to have them, repeating the same words! That’s why there’s so many friggin’ lyrics on there. That’s why you’re so naïve when you’re that age: you forget that the fundamentals of music exist for a reason. It was general pretentiousness. Having so many words and ideas, and trying to fit them into a limited space.”

Pretentious or not, it made Symphonies Of Sickness the one-off that it was. Another of its special qualities was the dual vocal approach: Steer delivered a gruff death metal gurgle, while Walker went for a paint-stripping scowl. In this case, variety was most definitely the spice of death.

“I never wanted to sing at all,” admits Walker. “When we went to Birmingham for the first album, the vocals were initially separated between Ken and Bill. Then I suppose my ego got the better of me and I started doing little bits and bobs. It ended up with me and Bill doing it, because for practical reasons Ken couldn’t do it live. Then Bill didn’t want to sing anymore, but on Symphonies… it was 50-50 between us. It’s a bit less lame than someone doing guttural, monotone vocals all the way through.”

Carcass had become one of the most important bands in a new movement which was rising towards the UK’s surface – also featuring Earache Records bands like Napalm Death and Bolt Thrower. “We were on a roll,” says Pearson. “I knew that some good things were happening with the label and the bands on it. A scene was growing, out of nowhere.”

“Around the late 80s and early 90s there were a lot of releases from Earache,” says Colin Richardson. “Looking back, a lot of them have stood the test of time. There was a real buzz about the music, before death metal burnt itself out for a while.”

Typically, Jeff Walker downplays suggestions that Carcass were at the forefront of a brave new musical world. “When we were making Symphonies…, there were probably about a couple of hundred people on the planet who would have given a fuck about that album. Back then, the rock magazines were all writing about fucking Guns N’ Roses and The Quireboys. That’s the reality. No-one was into music like Carcass. It was nothing like now, when extreme music supposedly rules the roost.”

- The life and death of Chuck Schuldiner: the godfather of extremity

- 13 Genuinely Terrifying Bands Who Definitely Aren't Faking It

He concedes that: “Our type of music started to get more popular, I guess, but it was still pretty uncommercial. Playing music like that, you weren’t gonna start selling loads of records. Even most of the extreme music around, from Slipknot to Evanescence has enough hooks and pop sensibilities to cross over. ‘Symphonies…’ wasn’t pop by any stretch of the imagination! It was the kind of music you had to sit down and study.”

To avoid being boycotted by record store chains, the album’s first vinyl edition bore a far more subtle cover, depicting a splattered head which had been artfully reduced to obscure white dots. Inside the gatefold sleeve, of course, the Faces Of Death-style gore remained – this time with a couple of chunks of animal meat for good measure.

On the eventual CD release, the splatter was on the front cover – perhaps because back then, CD wasn’t such a prevalent format. Later releases would again conceal the gore inside. Jeff Walker remains unsure about this: “It just doesn’t work as some lame cover,” he reckons. “That’s not what it was about. If you can’t handle it, don’t bother looking at it or listening to it.”

Symphonies Of Sickness would go on to sell more than a quarter of a million copies worldwide – an insane figure for such an extreme record. The band themselves would split in 1996, before reuniting in 11 years later (sadly minus drummer Ken Owen, who suffered a brain haemorrhage in 1999 that impacted on his playing). Since then, they’re released a fine comeback album, 2013’s Surgical Steel, with a belated follow-up, Torn Arteries, to follow later in 2020. But more than 30 years on, Symphonies Of Sickness remains a landmark for both the band themselves and extreme metal as a whole.

Published in Metal Hammer Presents: The Devil’s Music Vol.1