Blood and glitter. That is what we call it. Glitter and blood, not glam rock. So it is that on August 19, 1972, a sticky night in North London, a crowd of teenage girls and boys and older scene-makers are descending on the Rainbow Theatre. Situated on the corner of a run-down Finsbury Park thoroughfare opposite a menacing car lot, the Rainbow is a looming mass of red brick, whose featureless facade disguises an inner beauty.

Walk through the doors and you are transported into an Aladdin’s grotto where elaborate Romanesque mosaic floors, marble pillars and a central fountain in a vast portico hark back to the venue’s origins as a music hall and the 1930s cinema, the Finsbury Park Astoria.

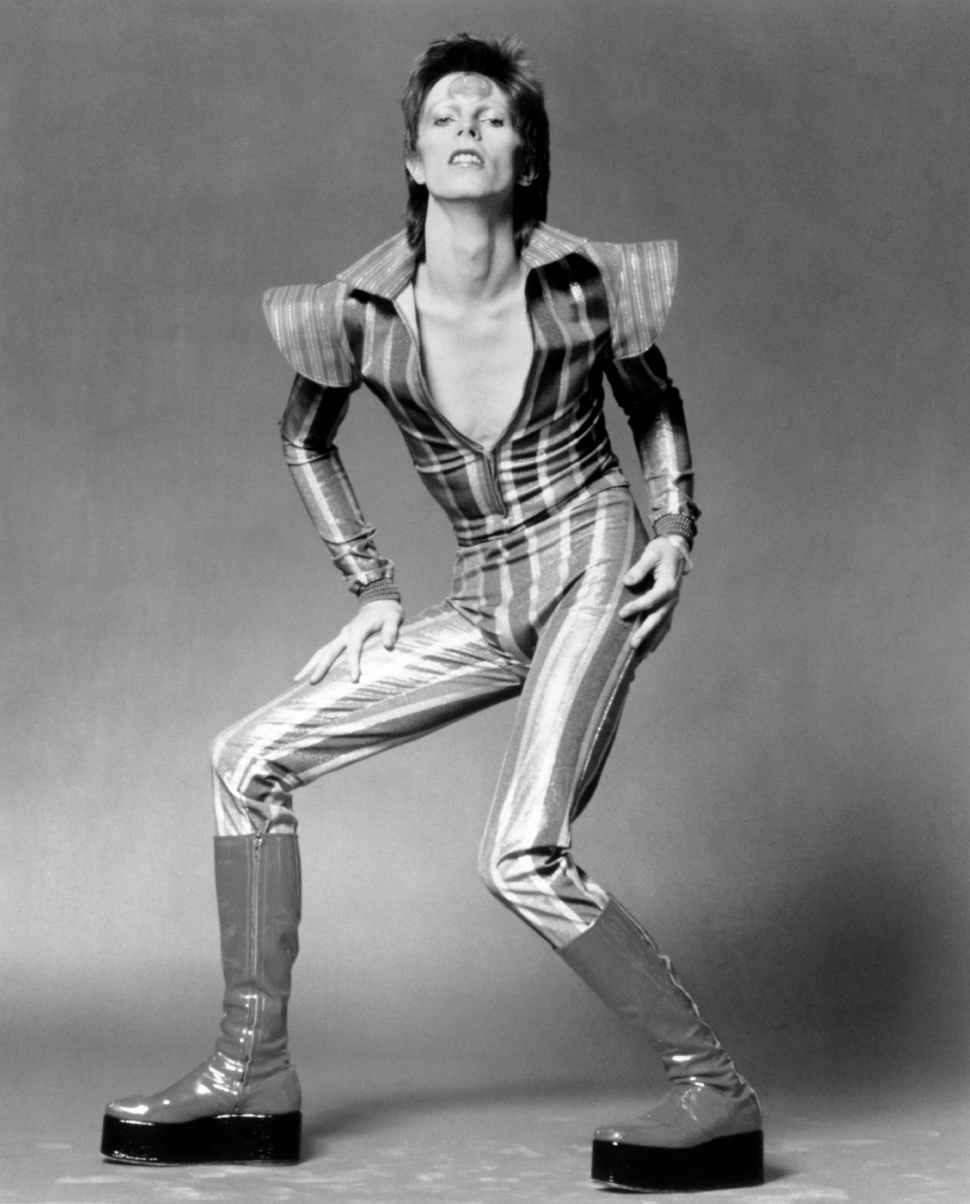

The hormonally charged throng could be starring in their own movie. They gather bemused looks from rush-hour passers-by and the boys in blue. Many of them are flamboyantly dressed and top their velvet jackets with spiked-up day-glo hair dos. There are boys wearing more make-up and glitzy jewellery than their girlfriends. Some sport skin-tight brushed denim South Sea Bubble loon pants, tucked into Jean Machine five-inch platform-soled boots.

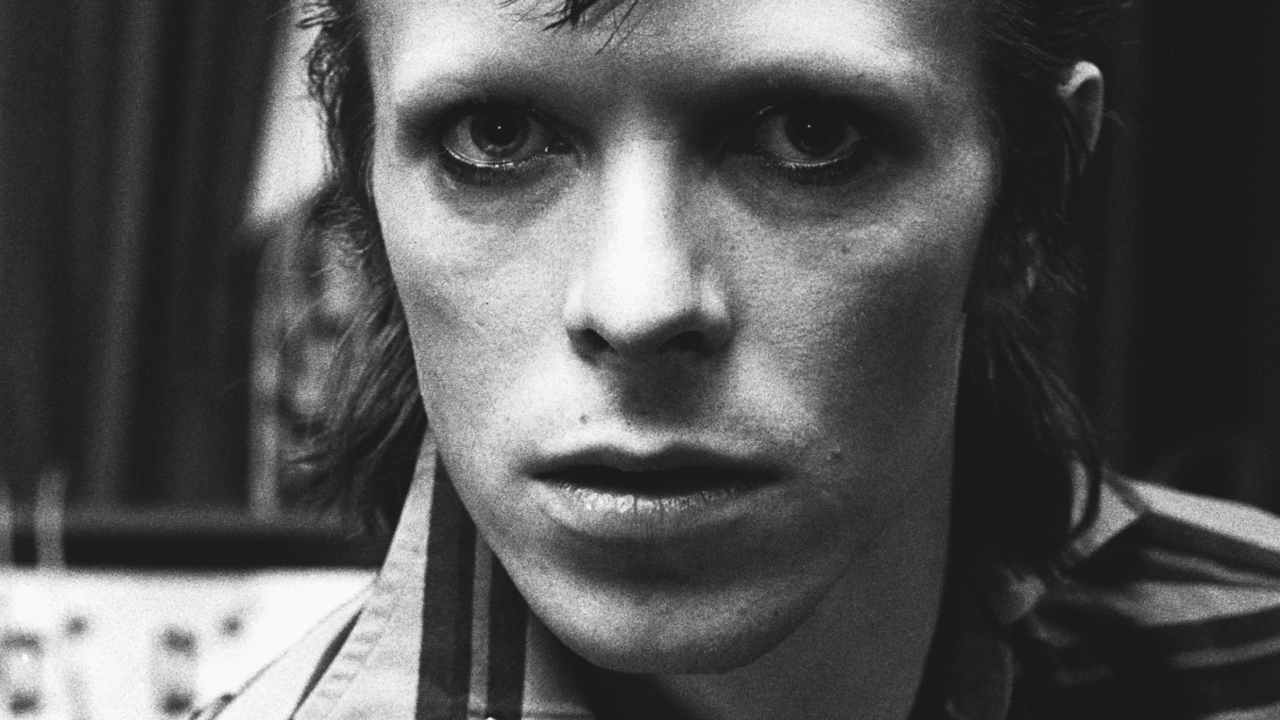

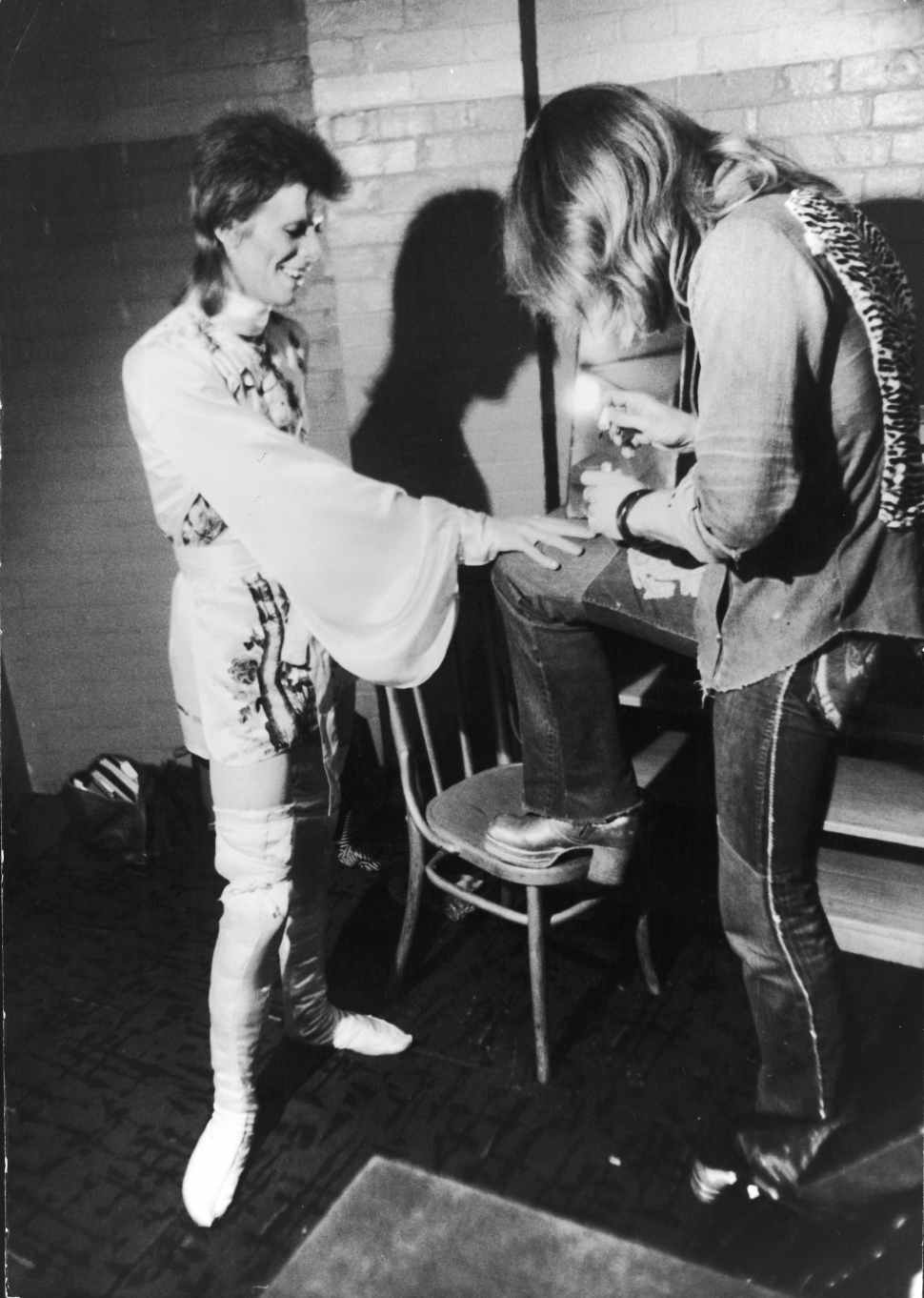

The early evening straights hurry past, tutting. Gaggles of skinheads wolf-whistle and shout insults of the “yer bleedin’ poof” variety. But it’s all water off a satin jacket as far as these kids are concerned. They have come to be the audience for David Bowie – their leper messiah – a 25-year old man who is teetering on the very brink of superstardom.

Tonight London will witness the official unveiling of Ziggy mania. The sign emblazoned above the Rainbow’s entrance simply reads: ‘This evening – Ziggy Stardust. Doors open 7.30 pm. Sold out.’ Good job we’ve got our tickets then.

Bowie’s rise to ascend the heights where rock gods lounge immortal is an astonishing tale of someone who has pursued a modernist’s Holy Grail – fashion, fame and immense wealth. His changes were legendary, his influence on popular culture a match for his own early heroes, The Beatles or The Rolling Stones – more specifically John Lennon and Mick Jagger.

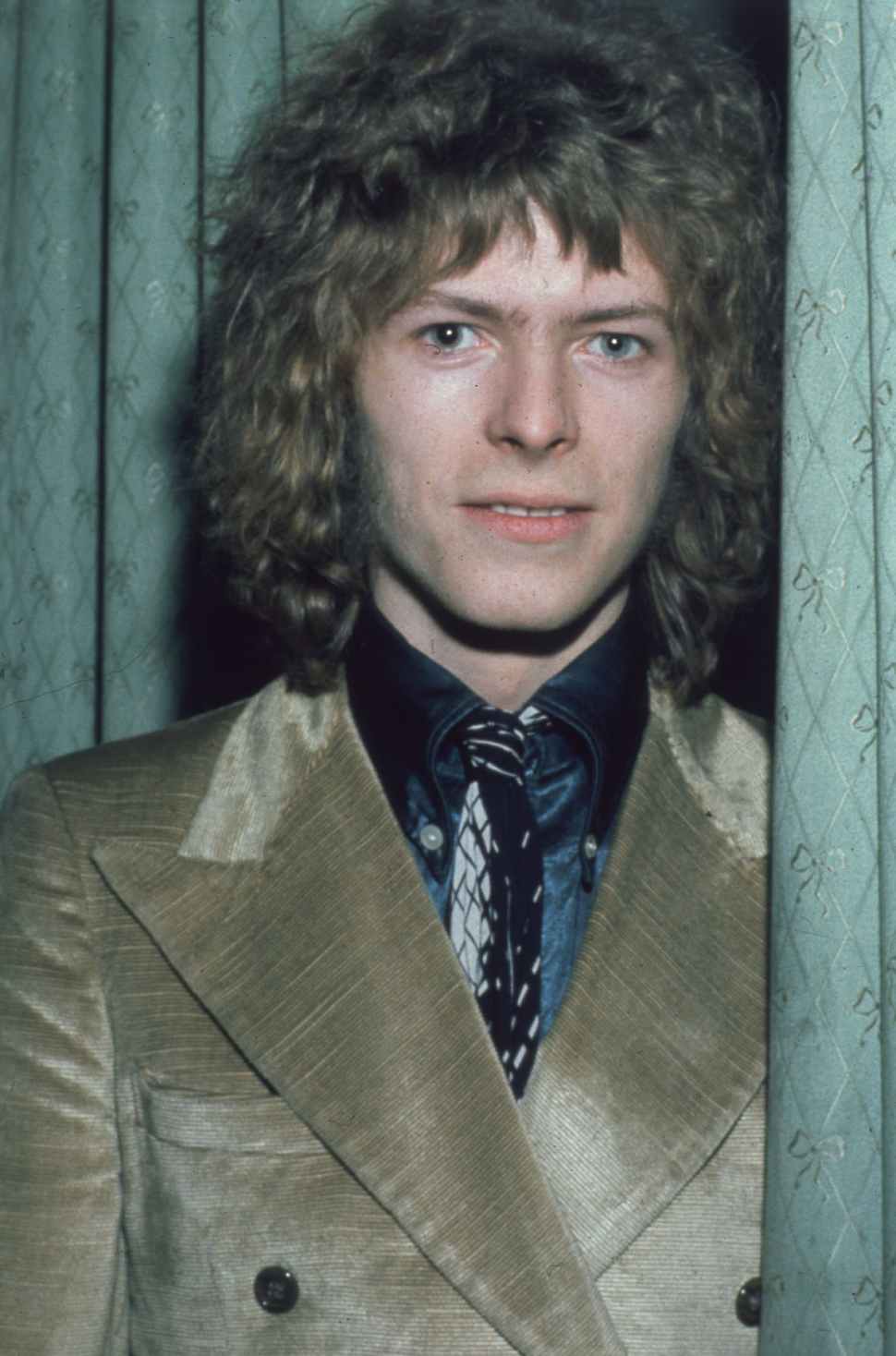

Bowie’s route to becoming a 21st century icon – for once that term is apt – took him from South London, where he was born David Robert Jones in Brixton on January 8, 1947 (sharing Elvis Presley’s birth date), to Carnaby Street hippydom. He graduated from being the chronicler of pill-popping London Boys to a Diamond Dog restrained on an S&M leash.

He was an all-round entertainer with old school values, and an innovator of the highest calibre. He was also a magpie, a Buddhist and a calculating bastard. A true friend to some, an enigma to more. Fortunately he was seldom boring, and for those of us who saw him at the Rainbow, and at concerts before, during and after the period 1967 to 1974, he made London seem as weird, interesting and sexy as any city on earth.

Bowie’s then in-house photographer and film promo man Mick Rock, who remained a close friend, is adamant that the Rainbow show was when the Starman fixed himself in the firmament. “He was a receiver throughout 1972 and that summer was magical. Bowie was a lightning rod. He was erupting.”

Speaking on the eve of his greatest triumph to date, an elated Bowie explained the Ziggy masterplan: “What I do and the way I dress is me pandering to my eccentricities and imagination. It’s a continual fantasy. There is no difference between my personal life and anything I do on stage. I’m rarely David Jones anymore. I think I’ve forgotten who he is.”

A decade later Bowie admitted that while had kept all his old stage costumes – “Stuff like that I’m very reluctant to throw away” – he had discarded his Ziggy alter ego with some relief. “I find it very refreshing to look at. It was an extraordinary phenomenon in rock at that time. I can’t really relate to the enthusiasm I must have had for him at the time. I’ve really cut myself off purposefully from him because he hindered my own physical and emotional state and it was such a hard thing to try and live his life. I really closed the door on him.”

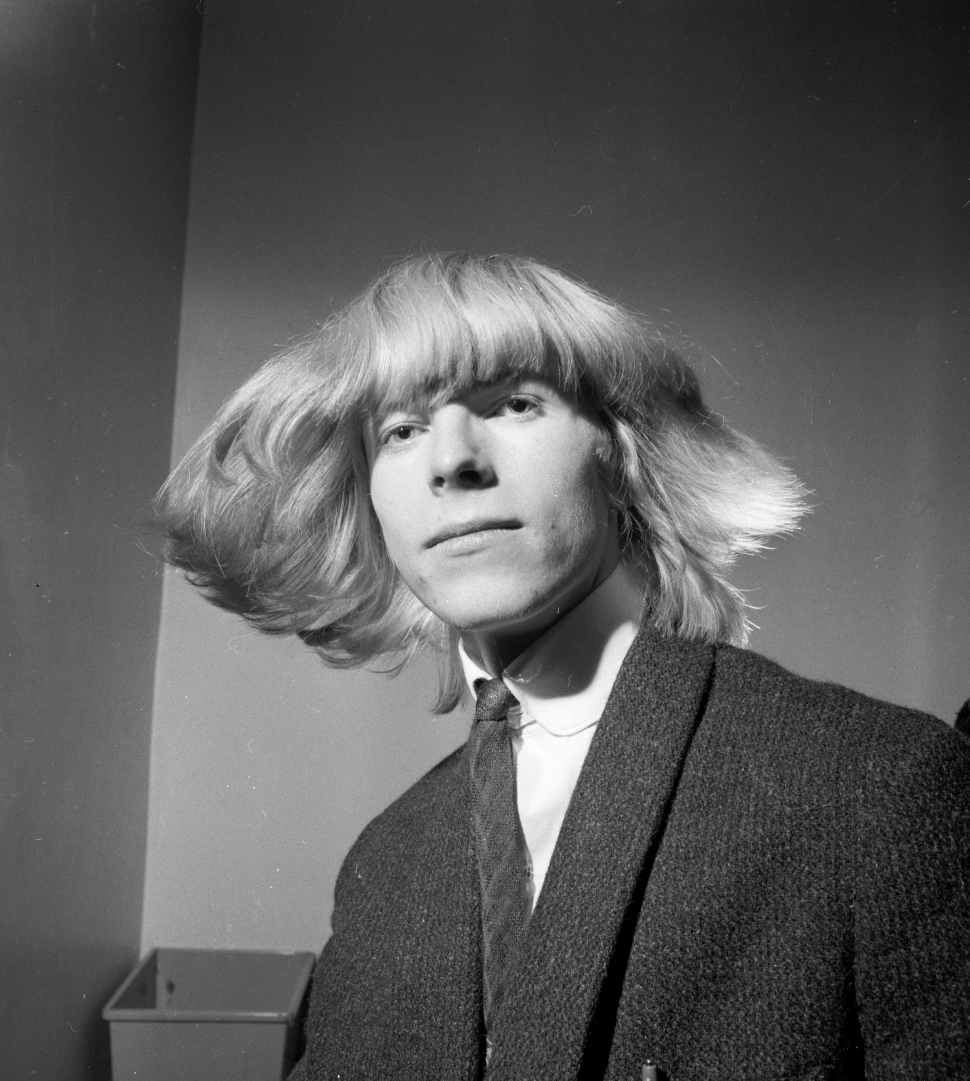

Faker. Fakir. Shaman. Showman. It was the latter quality that Ken Pitt saw one summer Sunday in 1965 at the Marquee Club on Wardour Street when he first set eyes on 18-year-old Davy Jones & The Lower Third during an afternoon residency. “I’d never seen anything like him,” said Pitt. “He was so theatrical and visual. The lyrics were superb. He had a remarkable charisma.”

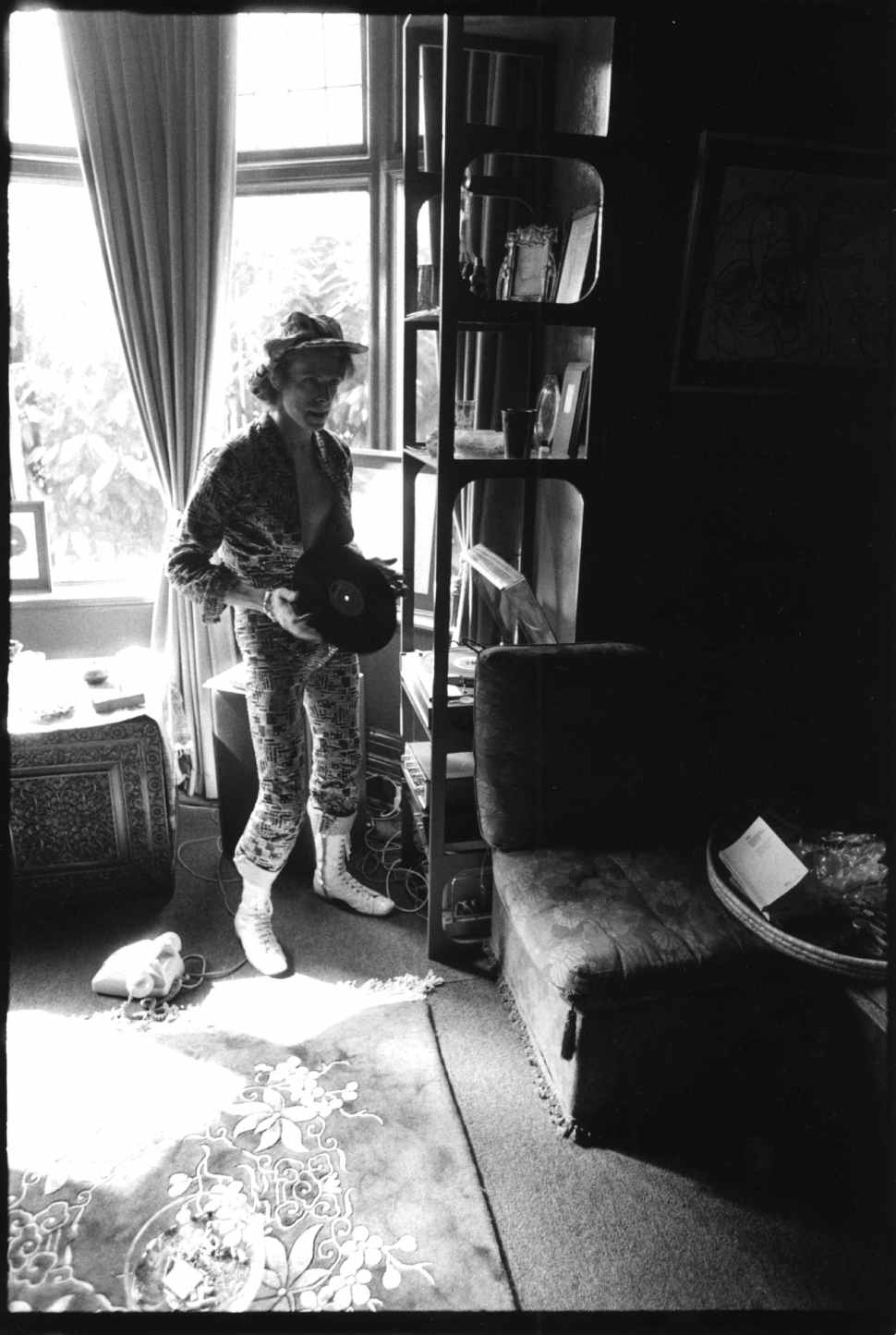

Pitt soon took over the management reins from Jones’s then mentor, Ralph Horton, and befriended a young man with avaricious reading habits. “We spent hours in my flat in Manchester Street, Marylebone, running the gamut on matters musical and literary. He had an intriguing way of sitting, with one leg pulled under the other which he dangled free and wriggled like mad. He always sat on the oldest and most expensive chair.”

It was at Pitt’s instigation that David Jones changed his name. Pitt, an impressario and press guru whose clients had included Frank Sinatra, Anthony Newley, Leonard Cohen, Manfred Mann, The Kinks, Jerry Lee Lewis and Bob Dylan, on his first UK tour, was an accomplished spin-master. During a visit to New York he noticed that David Jones of imminent Monkees fame was all over the billboards in Times Square and he wired Horton suggesting David took a stage name. “He wrote back saying he is now called David Bowie.”

The Pye Records press release accompanying Do Anything You Say, the first single under this new guise, claimed the name was inspired by Texan Ranger Jim Bowie, who gave his name to the one-bladed Bowie knife. Today, Pitt exclusively reveals this to be an apocryphal tale.

“A few years ago I discovered a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s Puck Of Pook’s Hill in my library, a book which Bowie would undoubtedly have seen in my flat. Inside the book is pasted a school certificate written in beautiful calligraphy, dated 1953, which reads: ‘Prize awarded to David Bowie. For effort.’”

While that must be one of the most significant cases of identity theft in modern times, Pitt’s influence on Bowie is immeasurable in other ways. During another visit to New York he went to Andy Warhol’s Factory studios, with the intention of bringing The Velvet Underground to London to play the Roundhouse. Warhol gave Pitt a pre-release acetate of the album that became The Velvet Underground & Nico.

Pitt recalls: “The banana on the cover was still hanging in the ceiling while I was there. When I got home I gave David the record and another thing I’d picked up by a sleazy band called The Fugs; or rather he pinched them and played them to death. Later on he said that hearing those albums, and meeting Lindsay Kemp, the mime artist I introduced him to, were the most vital aspects in his career change.”

Pitt also tried to interest Bowie in Bob Dylan, but the young man showed no interest at that stage. He was immersed in writing his first album for Deram, being particularly proud of a work in progress called The London Boys. In late 1966 the Buddhist-obsessed Bowie spoke of the song: “It goes down very well… but the words are a bit strong. I write most of my songs round London… the people who live in London – and the lack of real life they have. This song mentions pills and generally belittles the London nightlife scene. It’s risky because the kids aren’t familiar with all the tunes but I’m sure it makes their musical life more interesting.”

To Pitt The London Boys was Bowie’s first coming-of-age composition. “He spent a lot of time on Wardour Street observing the mods. He was always composing scenes in his mind and scribbling them down. The song is highly descriptive and moralistic but he also had a great sense of humour. We spent nights in Manchester Street laughing at his lyrics because they were so witty.”

Pitt, a venerable show-business gentleman of great tradition and integrity, stayed with his charge until the eve of The Man Who Sold The World album. He’d expressed reservations about the previous release, the so-called Space Oddity album, after detecting a folkier bent in Bowie’s writing. “He was becoming too Dylanesque. One day he came to my office with his future wife, Angela Barnett, and I told him this, though not in any strong way. He burst into tears and ran upstairs. He did that several times. He was very sensitive about his career in 1969 because although Space Oddity was a huge hit [helped by the BBC using it to sound-bed the Apollo 11 Moon landing] he was still struggling to make it big. He once wrote me a letter which read: ‘I’ve been trying so long! Oh, I do wish something would break for me!’”

Bowie and Pitt had already made an experimental film for £7,000 based on an earlier song called Love You Till Tuesday which included footage of the singer crawling around in a silver space suit to the prototype version of Space Oddity but the film was canned. The re-recorded single wasn’t issued for nine months.

However the Major Tom character remains one of Bowie’s more enduring creations and kick started a succession of space-inspired songs – Life On Mars, Starman and Ashes To Ashes among them.

Space Oddity itself owed a huge debt to Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, which Bowie saw on its release in September 1968. The 21 year old was so awe-inspired by Kubrick’s disembodied astronauts that he started to assume their mantle.

At the time Bowie told one reporter: “The publicity image of a spaceman at work is an automaton rather than a human being, and my Major Tom is nothing if not a human being. It comes from a feeling of sadness about this aspect of the space thing. It has been dehumanised, so I wrote a song-farce about it and to try and relate science and human emotion. I suppose it’s an antidote to space fever… Major Tom eventually gives up thinking completely… he’s fragmenting. At the end of the song his mind is completely blown. He’s everything then.”

This living in character until the role becomes an obsession is a key note in Bowie’s development. Not for nothing did he christen himself ‘The Actor.’ But as a 15 year old he’d been anxious for others to make an impression on him.

Phil May, leader singer of the legendary Pretty Things, was Bowie’s first rock’n’roll hero. “He came to see us play in early 1964 at the Brentwood Scouts’ Hut where we had a Sunday residency,” May told Classic Rock. “He used to play table-tennis there. Eventually we exchanged phone numbers. He had a shy persona but he was the most extrovert-looking kid in the crowd. I wasn’t surprised when he joined The King Bees and formed The Manish Boys and his R&B band Davy Jones & The Lower Third.

"One day he asked me for my new number and I said: ‘Give me your sketchbook or diary and I’ll write it in.’ He was reluctant and we had a tug of war over his book, but I grabbed it and looked under my name where he’d listed me under ‘G For God’. It was terribly embarrassing.

“Yeah, he was influenced by our sound and our long hair. We were said to have the longest hair in Britain when that meant you risked a good kicking and you couldn’t get served in a pub. David always checked out our gear too, the customised railwaymen’s jackets and junk shop chic remodelled by our art-school girlfriends.”

The then David Jones had aspirations to be a graphic designer, but he was a student of art rather than an art student. He left school with two GCEs in art and woodwork. May knows that The Pretty Things inspired Jones but felt that by the time he signed to Deram Records in 1966 he’d lost his R&B roots.

“We thought his music lacked edge. It was quite camp, all about fashion and image. The general view about him, when one spoke to our guitarist Dick Taylor [a founding member of The Rolling Stones], or The Yardbirds guys like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, was that he was too fringy. He wasn’t really taken seriously until he teamed up with Mick Ronson and locked his image to his music. In the mid 60s he was a good-looking young pop boy. There was a question mark: is this guy a heartthrob or a musician?”

May was certain that Bowie’s eventual metamorphosis into the dress-wearing bohemian who draped himself over the album covers of The Man Who Sold The World and Hunky Dory had conceptualised his vision after visiting the Transvestite Revue Bar in Paris; that he adapted his androgynous look from the Berlin school of decadent post-Weimar Republic figures like Brecht and Weill.

“The other significant thing he got was that certain singers like myself, Jim Morrison and Mick Jagger gave the straight boys in the audience a rock’n’roll hard-on. There was sexual chemistry for the men. It wasn’t all about screaming girls. He’s a bright guy, very well read and articulate, so he isn’t a bullshitter. He was always into William Burroughs, and he loved that Franz Kafka idea about viewing humanity as so many insects under a microscope.

"By the time of The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders From Mars, which is his best record, he was into the Japanese Noh Theatre, the Kabuki masks and the Lindsay Kemp mime, as well as the pathos of French theatre. Ziggy was this doll he’d been playing with for years, a marionette that he suddenly brought to life.”

While Bowie was adept at second-guessing fashionable trends, May reckoned he was equally interested in fame and wealth. “Definitely. He was changed by fame in the early 70s but he craved that change. It’s like – if you don’t want a suntan, don’t lie in the sun. Well he basked in it. And he is a chameleon and a caricature, like he says in the song The Bewlay Brothers.

“He has to have new things hitting him and he’s also a wealth seeker like Mick Jagger and Van Morrison. Some people become ruthless, like Genghis Khan. Or Chuck Berry.”

The core band that became The Spiders From Mars came together in June 1971 when bass player Trevor Bolder deputised for session man Herbie Flowers during a John Peel Session. Speaking from Hull, Trevor told Classic Rock how he met Bowie: “I saw him supporting Keef Hartley at Harrogate Opera House. Mick [Ronson, guitar] and Woody [Woodmansey, drums] were still in Ronno then, this is after The Rats, and David was playing solo acoustic 12-string and singing The Man Who Sold The World songs. He had long blond hair and looked like a regular rocker – not weird at all.

“A few months later I went to this rambling house he was renting called Haddon Hall and we rehearsed 12 songs in 12 hours for the radio show – all the stuff that ended up on Hunky Dory. A week later I got a call to go to Trident Studios on St Anne’s Court in Soho and we made the album in a few takes on a 16-track. There were no rehearsals. It was bloody nerve-wracking for me cos I’d never set foot in a studio before. David wanted it thrown together, mistakes and all. ‘Do it very natural,’ is what he said.”

By now Bowie, Angie and the band that became the Spiders were sharing the 30-room Victorian folly Haddon Hall in Southend Road, Beckenham. Trevor remembers this period with the greatest affection. “We all had the best times there. We were living together, doing Hunky Dory, going to the pub, playing football. There was a magical buzz in that house during the summer of ’71. It was an innocent time before the fame; the start of the journey.

“Everyone mucked in with cooking and cleaning. David lived in the main entrance hall with a grand staircase. He had a big white piano in his living room and his bedroom was very Bohemian and arty. The band were living upstairs in sleeping bags. The promise was that we’d be a proper group, we’d make the same money and it would be democratic. We loaded our gear up in the back of Bowie’s old Rover Stardust concept.

“I still had scruffy hair and clothes and a full beard,” Trevor laughed. “I was more into Fleetwood Mac than glam, not that it existed yet. One day David emerged with his new look, the spiked red hair and the padded clothes which he wore at Friars Club in Aylesbury in early 1972.”

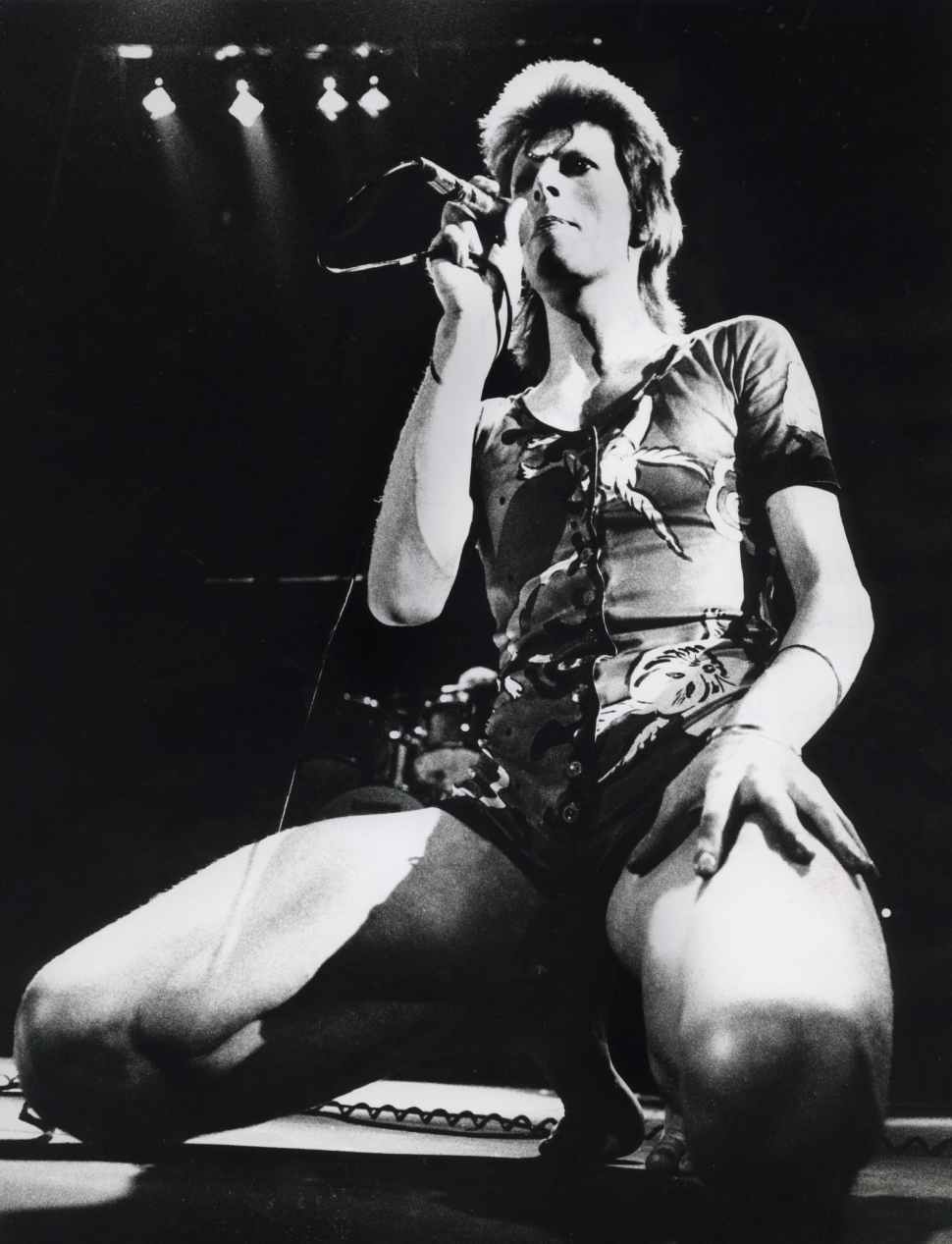

At Friars, Bowie introduced Ziggy to a handful of fans. Beforehand he announced what lay in store. “Our new stage act will be outrageous. But very theatrical. It’s going to be costumed and choreographed, quite different to anything anyone else has tried to do before. No one has ever seen anything like this. It’s going to be entertainment because that’s what’s missing in pop music now. There’s only me and Marc Bolan. The Beatles were outrageous at one time, so was Mick Jagger.”

In a dramatic echo of his own song Five Years, which is more to do with rock stars self-destructing than the end of the world, Bowie described his stance on stardom with chilling accuracy. “You can’t remain at the top for five years and still be outrageous. It’s impossible. You become accepted and all the impact is gone. Me? I’m fantastically outrageous. I like being outrageous. People want you to be outrageous. And I’m old enough to remember Mick Jagger!”

Ever the wind-up artist (the ‘chameleon, comedian, Corinthian and caricature’ of The Bewlay Brothers), Bowie was now flaunting his bi-sexuality, even though he was married with a son. To Bowie the rock star’s bent for homo-eroticism went back beyond Elvis Presley and Little Richard to late-19th century writers and artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde. If he wanted to wear a dress – a man’s dress, he insisted – well, so what? “I don’t have to drag up. I’m just a cosmic yob, I suppose.”

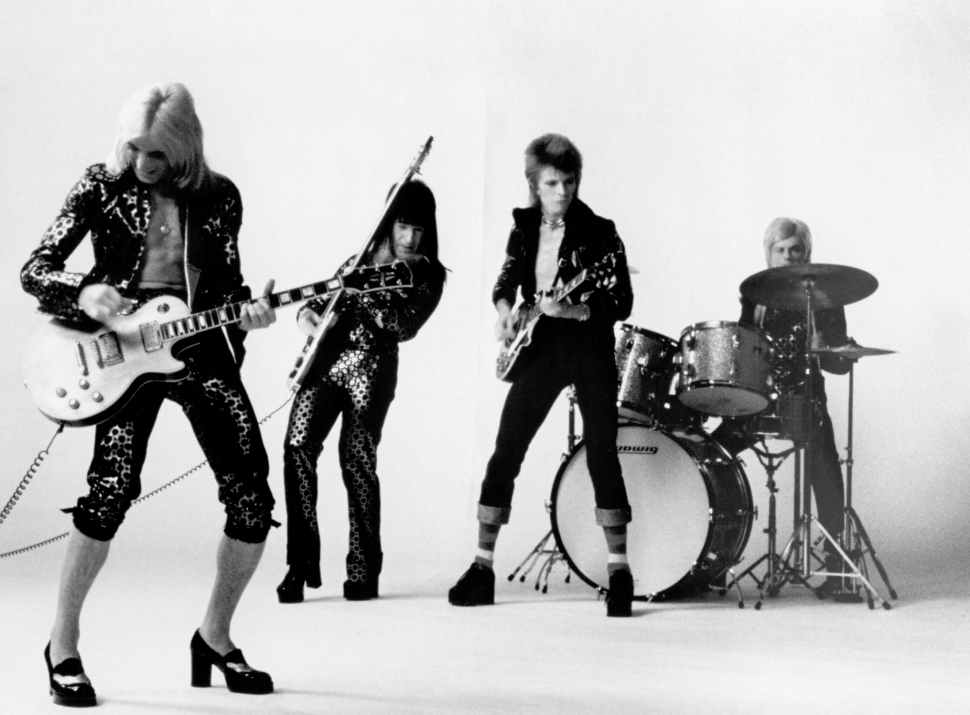

Trevor Bolder said claims of bisexuality took the band by surprise. “There were plenty of girls. I think he was spinning them along but it sold papers and therefore records, so we didn’t give a monkey’s.” As for the Ziggy Stardust tour that opened in January 1972, its primary influence wasn’t Star Trek-styled science fiction but the urban ultra-sex and violence of Stanley Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange, which Bowie had gone to see at the Warner West End when it opened the year before. He pinched the ‘look’ of the Spiders From Mars from the film’s protagonists, a bunch of half-witted thugs, or ‘droogs’, lead by a much cleverer character, the arch manipulator Alex.

Trevor Bolder: “We were his droogs, but it was Woody who decided we might as well become the Spiders From Mars and he put the name on the drum kit. David edged us into the clothes. Originally he wanted us to wear bowler hats and boiler suits like on the movie but we refused that do that so he commissioned our stage clothes.”

While Ziggy Stardust awaited its summer release, Bowie and company embarked on a tour of clubs and pubs, for which Bowie’s wife Angie did the simple lighting. In April the pre-album single Starman/Suffragette City was accompanied by two seminal TV appearances, The Old Grey Whistle Test, the only serious music show on TV, then Top Of The Pops. Both caused a furore.

Bowie’s effect on British pop culture was seismic and instantaneous. Suddenly the band were selling out Newcastle City Hall and Oxford Town Hall, where Bowie first ‘went down’ on Mick Ronson’s Les Paul and fellated the bridge. Mayhem ensued.

Trevor Bolder had only recently got rid of his beard but kept his magnificently preposterous sideburns at Angie Bowie’s insistence. “She sprayed them silver every night, then I’d wash it out after the gig. The Spiders never wore stage gear after a show, always back to jeans and T-shirts. Bowie kept his stage stuff on but we wouldn’t walk the streets looking like that. Too bloody dangerous.”

On July 8, 1972, just after the release of the Ziggy Stardust album, Bowie played at a Friends Of The Earth benefit, called Save The Whale, at London’s Royal Festival Hall. Utilising the venue’s magnificent acoustics he was in world class form, incorporating ladder-climbing mime into The Width Of A Circle (the opening track on The Man Who Sold The World) and introducing Velvet Underground leader Lou Reed, who he’d met in New York the year before.

This was Reed’s first ever British appearance and he performed his classics – White Light/White Heat, I’m Waiting For The Man and Sweet Jane. Reed, the subject of Bowie’s Queen Bitch on Hunky Dory, was visibly nervous since most of the audience hadn’t a clue who he was.

Later that month Bowie took Reed into Trident studios to record what became Reed’s Transformer album. But first Bowie knocked off a career-salvaging single and album for west Midlands rockers Mott The Hoople.

Ian Hunter, Mott’s then curly-haired singer, recalled that Bowie was a real fan of the Hoople. “He’d already offered us an early version of Suffragette City with a note saying: ‘A song for you to hear. Hope you’ll ring sometime and tell me what you think. Luv, David Bowie.’ We liked the song but it wasn’t in my register. I couldn’t make it work. Don’t forget that it was early 1972, and while we’d read about Bowie he wasn’t a superstar yet, so we turned it down.

“It was lucky we did, because All The Young Dudes was perfect for us. Bowie invited me to his manager Tony DeFries’s offices at MainMan on Regent Street. Bowie sat cross-legged on the floor and demoed it on an acoustic guitar.

“He was quite nervous and anxious. When he finished there was a short silence, then he said: ‘I thought that might do the trick?’ And I said: ‘Yeah, that’s fucking great. Thanks, we’ll do that one.’”

…Dudes, with its cast of inner-city urchins – Billy, Wendy, Freddy and Lucy – copied Lou Reed’s factional style but made the characters instantly recognisable to British kids, even though the lyric was cloaked in the same American hip argot – using words like rapped, speed jive, boogaloo, funky – that Bowie employed throughout Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust. The parochial cockney references to Marks & Sparks and boat race, not to mention the hitherto unheard-of trick of name checking T. Rex, The Beatles and the Stones, rooted the song in the minds of Bowie’s followers. It also made the unfashionable Mott The Hoople seem like avatars.

Ever mindful of real talent, Bowie had already decided Mott could be huge when he saw them on tour in 1971 and fell in love with the rapport they enjoyed with their fans: “I couldn’t believe that a band so full of integrity and a really naïve exuberance could command such an enormous following and not be talked about. The reactions at their concerts were superb and yet they were breaking up! I caught them just in time and put them together again because all the kids love them.”

As Hunter told Classic Rock: “It’s one of Bowie’s best songs ever, and he gave it to us. Which was incredibly generous. The song sums up a decade of rock culture in a few verses. The kids were an amalgamation of his fans, and he put himself inside their heads – which was a fantastic gift to have. He summarised a mood of rebellion and invented punk in that song as far as the British were concerned – only it was four years before punk happened.”

A young photographer called Mick Rock would also find himself caught in Bowie’s charismatic web in 1972. Rock, a Cambridge graduate who had befriended a post-Pink Floyd Syd Barrett, and who had taken the album-sleeve shots for Syd’s solo debut The Madcap Laughs, was readily accepted into Bowie’s inner circle.

“We were all young, life was fun and everyone was out of their minds on ambition,” Rock told me. “I saw David play at Birmingham Town Hall in front of 400 people in March 1972, started filming his gigs on a Bolex and selling little articles about him to the tits-and-bums mag Club International, and Rolling Stone in America. He was starting to get traction. Starman was top five when I took the famous shot of him grinding his gnashers into Mick Ronson’s crotch at Oxford Town Hall.”

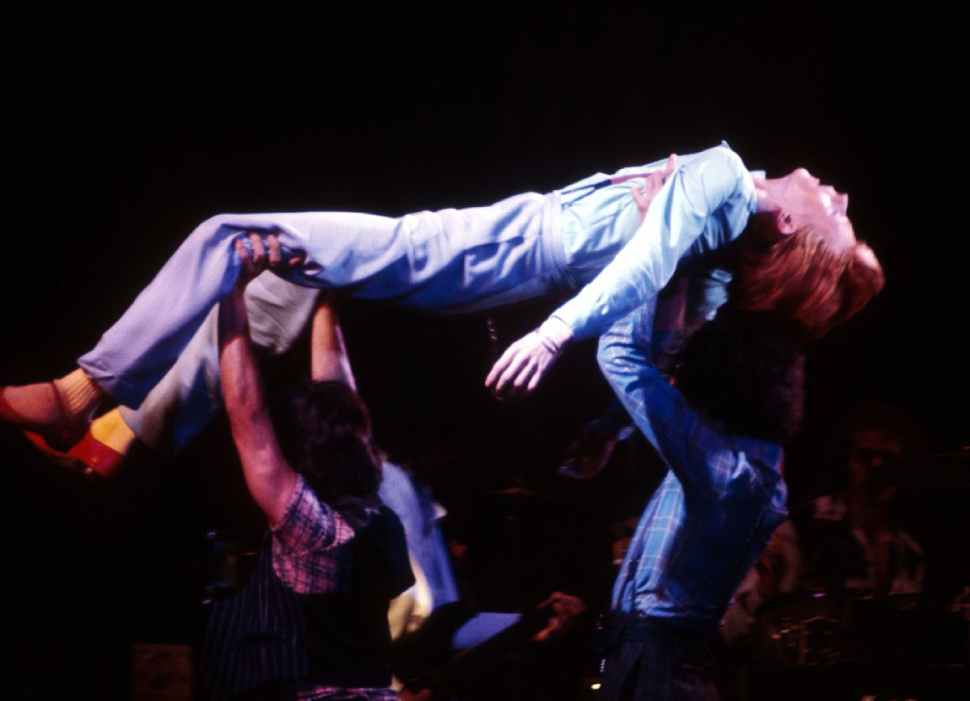

With Ziggy Stardust - both the persona and the album – about to explode, Rock captured a moment when Bowie’s synthesis of glamour, Kabuki and kinetic mime reached fruition. Rock was asked to make Ur-promos of Moonage Daydream and Rock’N’Roll Suicide – naïve collages, clips and stills with no synch sound – before embarking on a four-film sequence beginning with the bi-sexual epic John, I’m Only Dancing.

Rock remembered it well. “That was shot at the Rainbow, the seminal gig where Lindsay Kemp wore a pair of wings and clambered over the scaffolding smoking a joint, where Marc Bolan’s face was projected on the side-stage, and the Astronettes dance troupe accompanied him for a bizarre version of Over The Rainbow.’

Working to a £200 budget, Rock cobbled together what has been called the first rock video. Bowie lip-synched to a warped copy of the single on a cheap record player and the film editor had an epileptic fit during production.

They upped the ante somewhat by shooting The Jean Genie, Bowie’s tribute to Iggy Stooge/Pop in San Francisco, outside the Mars Hotel, with groupie Cyrinda Foxe in the starring role. Foxe and Bowie had a brief, tempestuous relationship and she later went on to marry New York Dolls singer David Johansen and Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler.

“I had more budget for that – four hundred quid!” Rock laughed. “We filmed David at the Winterland in San Francisco with a non-sound camera and then edited in one day with no cuts. At the end of the first American tour David called me just before he got on the QE2 and we made a film for Space Oddity at RCA studios in New York, making the consoles look like a spaceship. That was a good one.”

Rock’s final promo was made in June 1973 for the belated single release of Life On Mars, allowing his Johnny-come-lately fans to play catch up. By now Bowie had sold over a million albums, and even more singles, worldwide and was the biggest rock star on the planet. Even so, DeFries and MainMan only gave Rock £800 to fulfil his painterly vision of the star in full Kabuki/Aladdin Sane-in-a-suit garb.

“We had a London studio and a white backdrop and David looked fantastic. He was at his peak. We had two cameras and we also used stills, so it was relatively sophisticated for the era. It stands up. I didn’t make a single penny out of those films at the time. However, once David split from MainMan and made his final settlement he gave me the visual rights.”

Standing within the camp but with a voyeur’s gaze, Mick Rock was ideally placed to observe the Bowie phenomenon. “There was so much sex involved. In the imagery and the reality. Looking like he did was a fantastic ploy to get laid. To fuck the hip girls you had to look like a girl yourself. The 1972/’73 era was also when Bowie, Lou Reed and Iggy represented the Unholy Trinity.

“Their influence on the culture is fucking enormous, but it was David who waved his magic wand and rescued them. He brought that music out of the underground single-handed. The music was incredible of course, but it was far more than that. Without Bowie there is no punk, even though punk is the antithesis of the sex he represents.

“Before it became glam it was called ‘blood and glitter’. Glam was just a lifestyle. Roxy Music [who supported Bowie at the Rainbow Theatre] were a great band, but people like Queen, Cockney Rebel and so on… they were outriders, pretenders.”

Rock noticed a sea change occur when Bowie returned from America having made Aladdin Sane, the follow-up to Ziggy Stardust. “He was a mythological figure now. Even at Oxford and the Rainbow I noticed most of the audience were transfixed. When he killed Ziggy Stardust off at Hammersmith Odeon in July 1973 the audience were berserk.

“The crush during the ‘Gimme your hands, ’cause you’re wonderful’ finale in Rock’N’Roll Suicide was unbelievable. Girls were wetting themselves. I took one photo I call ‘the agony and the ecstasy’ because of these two young girls with golden Ziggy splodges on their foreheads. One girl is in ruins, and the other is obviously having an orgasm.”

The last three albums in Bowie’s career that marked the end of his desire to express a sense of otherness are the most problematic to assess. Aladdin Sane was designed to crack America, but its title character didn’t quite convince and the results are somewhat strained in parts.

Pin Ups, a homage to his 60s R&B heroes, was a fairly lame contract filler barely rescued by the version of The Merseys’ Sorrow (the original was recorded by The McCoys of Hang On Sloopy fame). Diamond Dogs, meanwhile, confirms the opinion that this trilogy represents the triumph of considerable style over less satisfying substance.

During their creation Bowie not only killed off Ziggy, which was fair enough – he’d always sung ‘the kids had killed the man’ – but he also ‘had to break up the band’. Yet during this time he concentrated on sharpening the production skills he’d learned from Ken Scott (this brilliant long-time Bowie overseer/engineer had worked with The Beatles and was often called Bowie’s George Martin), and immersed himself in the Warholisms of Lou Reed’s Transformer and Iggy Pop’s white-trash epic Raw Power.

But according to Trevor Bolder, these were not the happiest of times to be working with the Cracked Actor. Drummer Woody Woodmansey walked, or was sacked, after Aladdin Sane (though Bowie later admitted “Woody is the only drummer who has ever done exactly what I asked him to”) and Trevor faded away after Pin Ups.

“The differences were subtle,” Bolder told Classic Rock. “We had to crack America because Tony DeFries had borrowed so much money from RCA. The atmosphere wasn’t nice. I loved Lady Grinning Soul and The Jean Genie [the closing two tracks on Aladdin Sane] because they were second takes and the album was still recorded and mixed in a week, but everything else changed.

“In America David became separate and distant. He had his Andy Warhol and Mick Jagger entourage whereas me, Woody and Ronno were staying in a cheap hotel and going down the Village to get drunk. We weren’t arty enough for him anymore. There was friction. Pianist Mike Garson was now on board permanently [Garson had played at the final Ziggy show in Hammersmith] and he was earning far more than us. We thought: ‘Hang on? What’s going on here?’ So we saw DeFries before the Valentine’s Day gig at Radio City Music Hall and demanded a rise, or we were going home on the next plane.”

It was a Valentine’s Day Massacre for the old crew. “Bowie took offence, said we were disloyal and that we owed him everything, although we could barely live on our wages. The promised royalties never arrived and haven’t done until this day. He had the expensive lifestyle and we were being conned, but he still got annoyed.”

Loyal enough to hang around for Pin Ups, Bolder’s patience was wearing thin. “He [Bowie] blamed the band for the fact that Pin Ups was so lacklustre. He said he only made it because we were bored and needed summat to do rather than kick our heels. That was bollocks. He was in a hotel with RCA pressurising him to deliver and he hadn’t written anything, so we went to the studios at Château d’Hérouville, outside Paris, and he played all the old singles on a record player, told us to learn them in a few minutes, then we recorded ’em.”

Bowie was fully aware of his over-stretched limitations during these albums. Of the Aladdin Sane character he said: “He isn’t as clear cut and well-defined as Ziggy was. He’s pretty ephemeral. He’s also a situation as opposed to being an individual.”

As for America, his relationship with the country seemed to be love/hate. “The American is the loneliest person in the world. It’s very sad. So many people are unaware they are even living in America. It’s a bit serious, isn’t it?”

On completing the latter album he was at his wits’ end as he crawled off the Orient Express in Paris and then returned to his rented flat with wife Angie and his two-year-old son Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones. Tour fever had really kicked in: “I just want to bloody go home to Beckenham and watch the telly. This decadence thing is a bloody joke. I’m very normal… That whole hype thing was a monster to endure. I had to go through a lot of crap. I never thought Ziggy would become the most talked-about man in the world. I feel like a Doctor Frankenstein. What have I created?”

Pianist Mike Garson saw all the madness from an outsider’s viewpoint. “He wanted to move on to the next level with the Aladdin Sane album and maybe the songs were greater than the sum of their parts. The tours were unbelievable – it was like a new Beatles phenomenon. But Bowie was still pulling it off. He has innate talent.

“Diamond Dogs? That was a hard album to listen to but it gets better in retrospect. When we made it at Olympic in Barnes the atmosphere was dark. There was a black vibe. It felt like we were working in a dark place – except that Candidate and Sweet Thing are as good as anything he’s ever done. There was a freakshow, for sure. I knew there were drugs around the New York scene but I turned up with my family and played my parts. I’ve seen enough jazzers on heroin and rockers on coke, and that has nothing to do with me. I kept on my game. Either that or you end up in rehab. Or you die.”

For Bowie, who used to insist that the Spiders steer clear of any drug-taking – just the beer, lads – America became a drug in itself. He embarked on his own ‘Lost Weekend’ before he teamed up with John Lennon for Fame and the Young Americans album. His experiences with cocaine nearly killed him in the mid 70s when his weight plummeted to seven stone and he lived on a diet of milk, sleeping pills and South American chemicals.

But before the lights are dimmed and he comes on stage at the Rainbow in August 1972, while the crowds are streaming down the Seven Sisters Road, there is a man in a dressing room about to live out the fantastic dreams of a generation.

A man who later admits: “I am a good actor. The characters I’ve presented in the past worked. A bit too bloody well. I never wanted to be regarded as the leader or the forefront of any movement. I never wanted that. I want to be regarded as an individualist, not the leader of any school of rock. I’ve always been an entertainer. That’s about it.”

Somewhere, deep beneath the surface, maybe David Bowie really is still plain old David Robert Jones, after all.

The original version of this article appeared in Classic Rock 112, published in November 2007