In 1954, the popular high-street retail chain Woolworth launched its own record label, Embassy Records, to help feed, or perhaps more accurately exploit, the growing appetite British teenagers were getting for rock’n’roll music imported from America.

Newcomers in a competitive market, the label’s unique selling point was that they could commission soundalike copies of the most popular songs on the US ‘hit parade’ within days of their release, and make them available on vinyl in Woolworth’s department stores across the country at a significantly lower price than the original recordings. As Ian Paice recalls, there was but one minor flaw in the company’s cunning corporate plan.

“Those knock-off records were crap!” he says with a laugh. “They were recorded quickly, by a bunch of average English musicians in a cheap studio, and they sounded so flat and lifeless. Now the original records, they still sing. You put them on now and the magic is still there. Listening to them you can totally understand why a whole generation moved away from jazz and be-bop and said: ‘I like this!’ Those records switched our generation on. And those memories continue to inspire us, even now.”

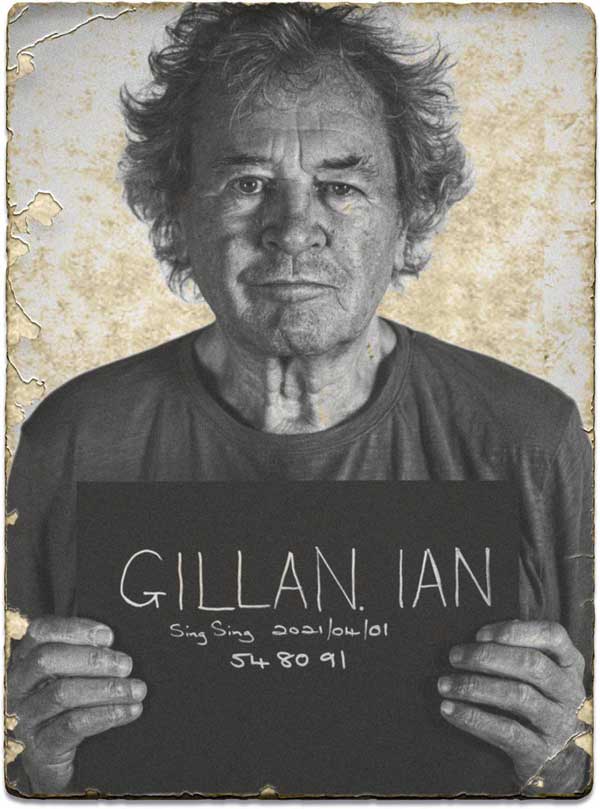

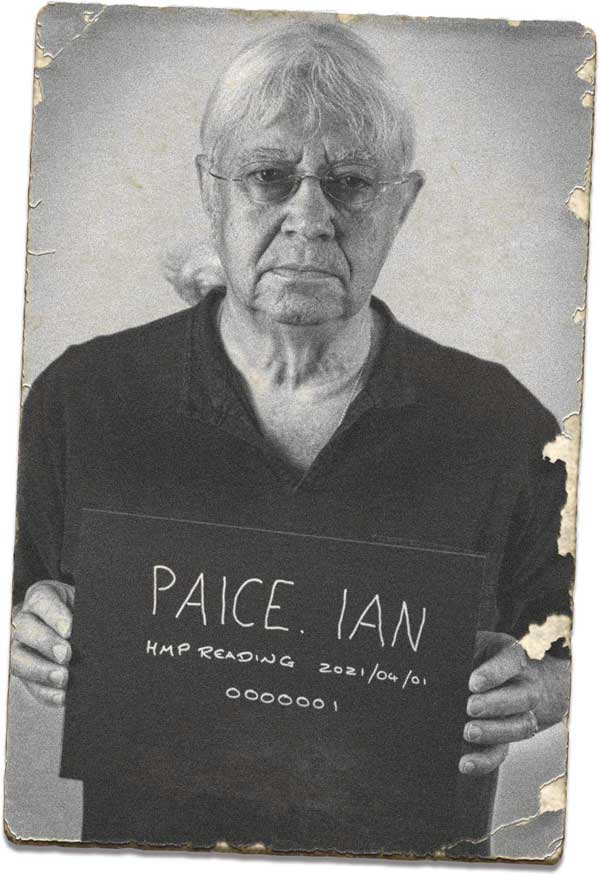

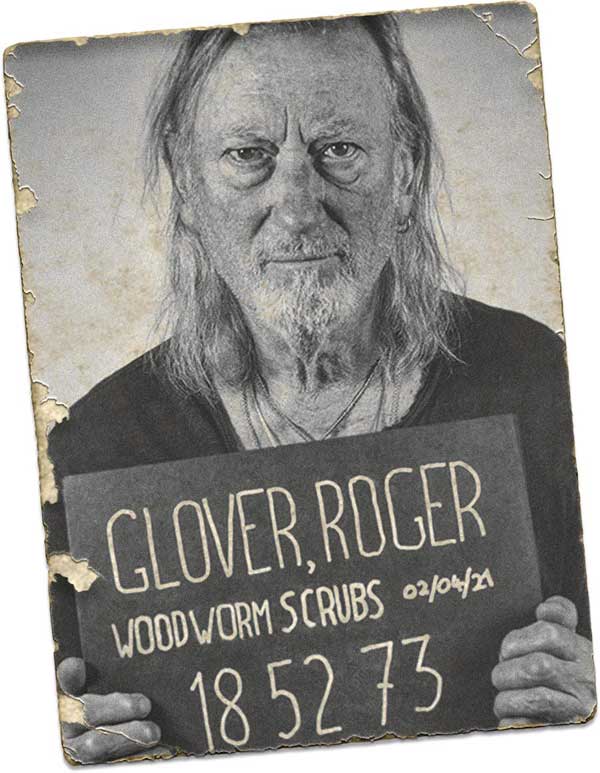

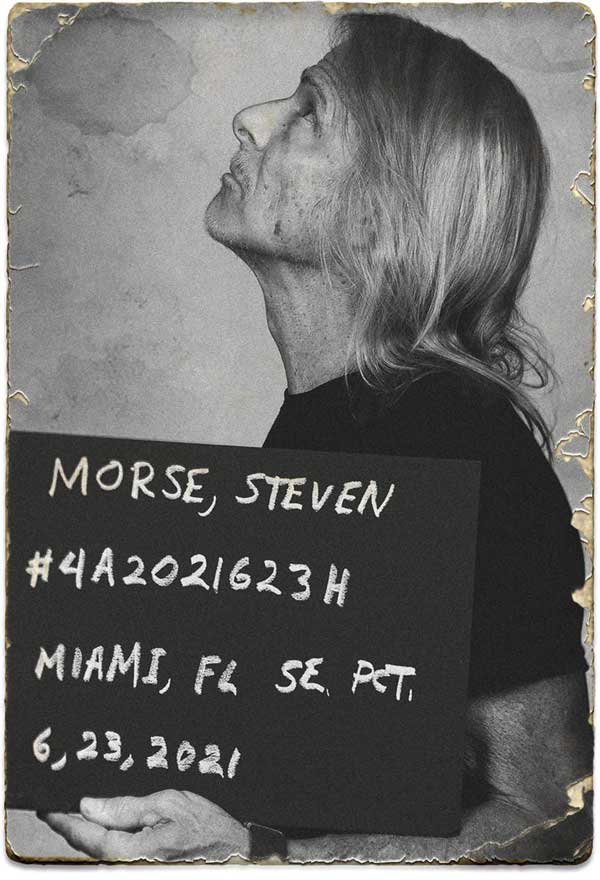

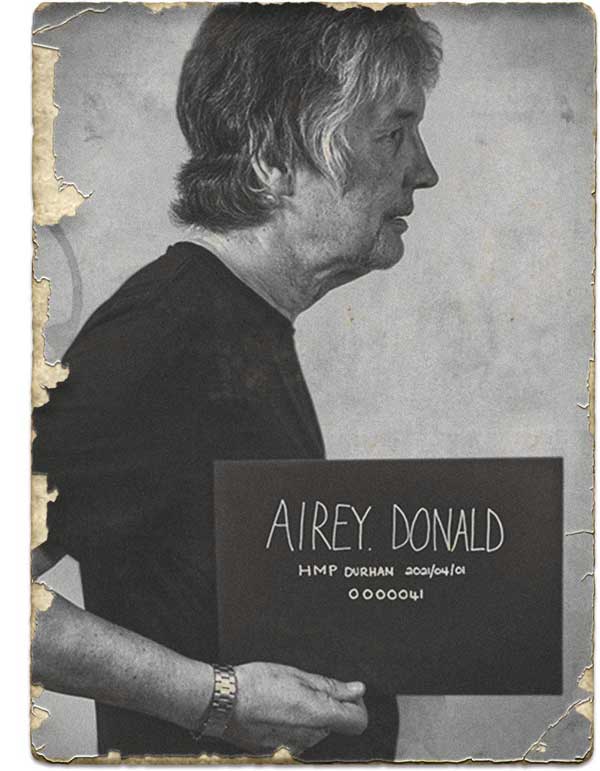

On September 6 this year, a new website, TurningToCrime.com, materialised online. It featured police mugshot-style black-and-white images of Ian Paice and his Deep Purple bandmates Ian Gillan, Roger Glover, Steve Morse and Don Airey, plus a countdown clock scheduled to hit zero one month later, on October 6.

Online speculation converged to suggest that this activity, hosted on a domain owned by the group’s Hamburg-based record company earMUSIC, was intended to tease an imminent announcement of new music from the quintet. Come October 6, this prediction was shown to be correct. Or at least technically correct, as the website revealed that Turning To Crime, Deep Purple’s twenty-second studio album, eventually released on November 26, would be a collection of songs previously recorded by other artists.

If the prospect of a new Purple album emerging just 15 months on from the August 2020 release of their rather excellent Whoosh! was a welcome surprise for fans, the notion of the legendary English group – rightly acclaimed as one of the most influential, and boldest, architects of the hard rock genre – returning as a covers act in the twilight of their distinguished career sat uneasily with many – not least, as it transpires, with certain members of the band.

“Oh, I was totally against it to start with,” Ian Gillan admits breezily, phoning from his property in Portugal. “I thought that Purple purists, myself among them, would see something like this as criminal, metaphorically speaking, so initially I didn’t like the idea at all. And then I started tapping my fingers on the desk at home, and thinking: ‘Hmmm, well, what are we going to do for the next year if nothing is happening?’”

As has been the case on any number of occasions during the past decade, the more cautious members of Purple were coaxed and cajoled into taking a leap of faith by their most trusted collaborator, Bob Ezrin, the free-thinking, risk-embracing studio legend behind the console for such landmark recordings as Pink Floyd’s The Wall, Destroyer by Kiss and Alice Cooper’s Billion Dollar Babies.

At the band’s very first meeting with the Canadian producer, in Toronto in 2012, they were challenged to direct the musicality, spontaneity and daring sense of abandon that powered their most celebrated live performances at the peak of their 70s success into their contemporary studio work.

Having pledged to commit to this collective mind-set, the five seasoned musicians rediscovered a sense of liberation in their playing and writing, and hit a creative hot streak with the three albums made under Ezrin’s direction:, 2013’s Now What?!, 2016’s Infinite and last year’s playful, powerful Whoosh!

When I last interviewed the band, in the summer of 2020, each of them credited Ezrin’s role in revitalising a musical institution that had, as Roger Glover admitted, somewhat lost its sparkle prior to his Toronto pep-talk.

“At our peak, we were dangerous, we were unpredictable,” Glover declared. “And we still are on a good night. It still feels fresh.”

Denied the opportunity to bring Whoosh! to life in concert halls across the globe by a paralysing pandemic, Purple were urged by Ezrin to find new avenues of expression.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if in six months’ time we’re so bored that we think: ‘Okay, let’s get back together and do another record,’” Ian Paice told me in late June 2020, half-joking, as an air of uncertainty clouded all attempts to look to the future. Remarkably, and somewhat to their own surprise, that’s what Deep Purple did.

Each new journey begins with a single step, and the road map leading to the creation of Turning To Crime was first drawn up after each band member submitted their own list of songs to Bob Ezrin for potential inclusion on the album, then participated in a democratic vote to narrow down the longlist to an agreed shortlist.

“As the song ideas started coming in,” says Ian Gillan, “our attitude became: ‘Well, let’s try a couple and see how it goes.’ Then once you have momentum, it takes on its own drive.”

When votes were tallied, Fleetwood Mac’s Oh Well had made the cut, as had The Yardbirds’ Shapes Of Things and Cream’s White Room, each of those an undeniable classic. But there were more esoteric nominations selected too, among them Bob Dylan’s Watching The River Flow, Love’s 7 And 7 Is, and Ray Charles’s take on Let The Good Times Roll. As a firm track-list began to coalesce, so enthusiasm for the project grew.

With covid-19 restrictions ruling out any possibility of the five musicians assembling under one roof to knock around ideas on arrangements, song structure and instrumentation, as has been their traditional tried and trusted methodology in album preproduction, instead Ezrin oversaw the distribution and development of the source material with each band member. It was a time-consuming creative collaboration not unlike the children’s party game Pass The Parcel, except with layers being added, rather than stripped away, before being handed on to the next participant.

Speaking at his home studio, where much of the album’s bedrock demo recordings were tracked, Glover chooses the words ‘illuminating’, ‘refreshing’ and ‘challenging’ to describe the painstaking process.

“I kinda enjoyed being alone and working without interference from Bob or the others,” the bassist says with a smile, before stressing Ezrin’s importance to the new system: “If Deep Purple is a wheel, Bob is the hub,” he states.

Reflecting upon his own approach to breathing new life into the album’s song selection, Glover reveals that he sought to tap in to memories of a creative environment he found inspiring before signing up to Purple Mk II in 1969.

“There was a great sense of freedom that happened in the sixties,” he enthuses. “All of a sudden you didn’t have to adhere to a set template, every song didn’t have to talk about love, you could do anything you wanted to. And that sense of freedom was the magic of the sixties, really. There was such an explosion of free expression. It didn’t last, of course, and it’s a different world now, but we still revel in pushing beyond what’s expected of us.”

“There’s no point in doing these things if you’re going to slavishly copy the original,” says Ian Gillan, a songwriting foil for Glover since the pair’s time in pre-Purple band Episode Six. “But at the same time, it’s awfully cheeky to think that you can improve on the originals, which are embedded in everyone’s mind. We took these songs on because they’re great songs performed brilliantly in the first place, and they’re part of our heritage, part of our lives.

"We play each song with complete respect, and hope that our personality and style has developed to the point where we can give it the Deep Purple identity without taking anything away from our respect for the original.”

The album’s opening track, and lead-off single, Love’s 7 And 7 Is, is a part of Gillan and Glover’s shared history, the pair having first performed the song with Episode Six. For Gillan, hearing Purple’s new interpretation of the track, originally written by Arthur Lee and released as a single by the Californian band in July 1966, was a watershed moment in the album’s genesis.

“I couldn’t believe the energy,” he marvels. “It was just exploding. The band sounded like kids in a garage again. And then I heard the Ray Charles song… Wow, unbelievable,” he continues. “I think that was the clincher for me to fall in love with this record. I got on my knees and bowed to the guys for putting that track together. To me it’s incredible, it’s everything I love about Deep Purple.

“I’ve said this before: Deep Purple is primarily an instrumental band. So we approach songs from that point of view first of all, and then my vocals are a kind of afterthought. I don’t think I contributed much to the final tracklist, to be honest – most of my ideas were struck off! – but it was such a joy making this record. I was laughing my head off in the studio.”

While expressing admiration for each of his bandmates’ input to Turning To Crime, Gillan has special praise for the contributions made by Steve Morse, a man many Purple fans still view as the group’s ‘new’ guitarist, even though he’s now in his twenty-seventh year with the band.

“Steve brings a different element into the band that we’ve never had before, because of his wealth of knowledge of jazz and southern rock and different approaches to music,” Gillan explains. “It’s given the band another dimension.”

For Morse, there’s a neat life symmetry to Turning To Crime, in that the easy-going Ohio-born guitarist recalls that one of the first Deep Purple songs he ever performed with high-school bands was the their 1968 hit cover of Hush, written by American singer-songwriter Joe South, and originally recorded by country soul singer Billy Joe Royal one year earlier.

In reflecting upon the place of cover versions in his own musical education, the 67-year-old Morse cites The Byrds’ take on Bob Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man, released as a single just one month after the original opened the acoustic side of Dylan’s 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home, as a track that “came alive” and “revealed its magic” to him in its new setting, where Dylan’s own recording had rather washed over him without making a lasting impression.

Of the five band members, it’s Morse who appears to be the most acutely aware of the fact that bending classic songs into new forms is viewed as heresy by some more conservative music fans. It’s a lesson the guitarist says he learned first-hand after recording alternative takes on six classic Ozzy Osbourne songs with original Blizzard Of Ozz band members, and song co-writers, Bob Daisley and Lee Kerslake, and Australian vocalist Jimmy Barnes (plus guest keyboard player Don Airey), on the self-titled debut album by the short-lived hard rock project Living Loud, released in 2004.

“We tried out some different things with the songs that Bob really liked, and ended up with something a little bit different. And my god, the floodgates of hell opened up! People lost their minds. So here [with Turning To Crime] I’m prepared for some backlash again.

"But I guess there’s always the possibility that some people might like it,” he adds with a knowing chuckle.

For his part, Ian Gillan displays a sense of Zen calm when asked to consider what Deep Purple fans might make of this unexpected late-career curve-ball album.

“I know this sounds stupid,” he says with a chuckle, “but we’ve never, ever sat down, when coming up with ideas for an album, and thought: ‘I wonder what the public would like.’ Never, ever, once. It’s all organic, and it all comes from within the band, and when we do something we do it one hundred per cent and have a crack.

"We’ve been around the block a few times, and I really love this record. You can always tell if you genuinely feel proud of a record if you play it a few times and really listen to it – which isn’t that case with all the records that I’ve made! But I have played this one, and I’m very happy with it.”

Gillan’s enthusiasm is infectious, and clearly genuine. Much like Ian Gillan And The Javelins, the likeable labour of love in which in 2018 the vocalist reunited with the dance band he fronted as a teenager in the early 1960s to cover rock’n’roll, blues and soul songs, Turning To Crime can be viewed as a love letter to the five musicians’ formative years, imbued with their warm and still vivid memories of having their teenage minds blown and lives transformed by a seemingly endless deluge of electrifying seven-inch singles. There’s something wonderful and heart-warming about seeing seasoned pro musicians turn into wide-eyed teenagers again as memories of those days flood back.

“Back then the musical landscape was being re-drawn constantly,” marvels keyboard player Don Airey. “We were always waiting for the next Beatles song, or the next Stones song, which were always six weeks apart, and we kinda took all this great music for granted. And then of course Jimi Hendrix erupted on the scene, and then British blues turned into British rock, with Zeppelin and Sabbath and Purple.”

It was just mind-blowing when you saw bands like that,” he continues. “Whatever you thought you knew at the start of the gig, you left that venue as a different person. If you saw Ritchie Blackmore playing back then, or [late Purple keyboard king] Jon Lord playing, it was like nothing you’d ever seen before: the volume, the skill, the interplay with Ian [Paice]… it was unreal, devastating. Even if you knew the songs, you didn’t know what was coming next.

"And there’s some of that spirit of adventure, to me, on this record. With some of the arrangements that Steve did, going off at tangents on songs like Oh Well and Lucifer, adding his own take on things, that’s very exciting when the unfinished track comes down the wire to you. It’s like: ‘Oh, what’s he done there?’ And as a musician, the question of every day is always: ‘What can I do today to make this sound better?’

“For me, this record conjures up some wonderful memories,” Airey adds. “I never saw Cream, but I did see Eric Clapton playing with [John Mayall’s] Bluesbreakers at a university gig, and it was amazing. I didn’t really know what I was seeing, but you could tell something was going on. It was quite incredible.

I remember Gary Moore telling me a story about him seeing Cream at his father’s ballroom in Belfast. I think Gary was thirteen or fourteen, but he was allowed to stay up to watch Cream. What he remembered of the night was seeing row upon row of grown men with tears streaming down their faces at Eric’s playing. The power of music to touch hearts and change lives is never something we take for granted.”

Turning To Crime conjures memories for Ian Paice too. Of Purple’s first shows in America with Cream, of US tours and drinking sessions with Fleetwood Mac; of precious black vinyl discs that showed him worlds he never knew existed, at a time when he’d yet to travel outside of his home town Nottingham.

“This album is meant to be fun,” he insists. “It’s a homage… not always to the actual songs, but to the spirit of the songs, which, when we were kids, made us want to play rock’n’roll, to take a whack at it too. When I was kid I remember buying a couple of Yardbirds singles, and boy they were exciting. Like they were on stage, not in the studio. Nobody was being careful or safe, it was like somebody stuck a few microphones in front of them and captured it. That rawness really came through.

“And I tell you what, we’ve made a great sounding record too,” he says with a grin. “When you stick it on loud it doesn’t half kick your ass!”

Roger Glover, Paice’s partner in rhythm, gets thoughtful and reflective when weighing up where Deep Purple are in 2021. While he confesses to a certain amount of frustration that the band have yet to have the opportunity to play songs from Whoosh! on stage (Purple’s last concert took place in Mexico in March 2020, five months before album twenty-one was released), he’s quick to stress how “privileged” he feels to still be part of an active, working rock band, and one regarded as a cornerstone of our world.

“I think we still have another ‘proper’ Purple album in us,” he says,“but this was a great dive into nostalgia for us.” “In some ways,” he muses, “the covid lockdown was like a dress rehearsal for our retirement. And as much as we all loved the opportunity to have all this additional time with our families, it’s clear that none of us are ready for a life without music and artistic expression just yet. We have so much fun doing this band.

"We know we can’t go on for ever, but the idea of stopping isn’t a nice one, and right now it’s not a consideration. It’s hard to explain exactly why we’re still here fifty years on, but with this new record being a wonderful reminder of why we do what we do, that’s a question we can save to answer on another day.”

Turning To Crime is out now via earMUSIC.