How Hysteria took Def Leppard to hell and back

The massive-selling Hysteria turned Def Leppard into global superstars, but recording the album took the band to hell and back – more than once

Def Leppard were under no illusions about what they wanted to do: they wanted to become the biggest band in the world, and were prepared to do whatever it took to achieve their ambition.

Perhaps if they’d known exactly how much ‘whatever it took’ would turn out to be, they’d have knocked it on the head and got a job at B&Q. But it’s a good thing they didn’t, because the album that resulted from their very real battle against extinction turned out to be one of the classic British rock albums.

By February 1984 Def Leppard were already a big deal – well, in the USA anyway. The band that started out in a spoon factory in Sheffield had a respectable count of massive US gigs and six million sales of 1983’s Pyromania to their name when they settled into a shared house in Dublin to start the grand cycle all over again.

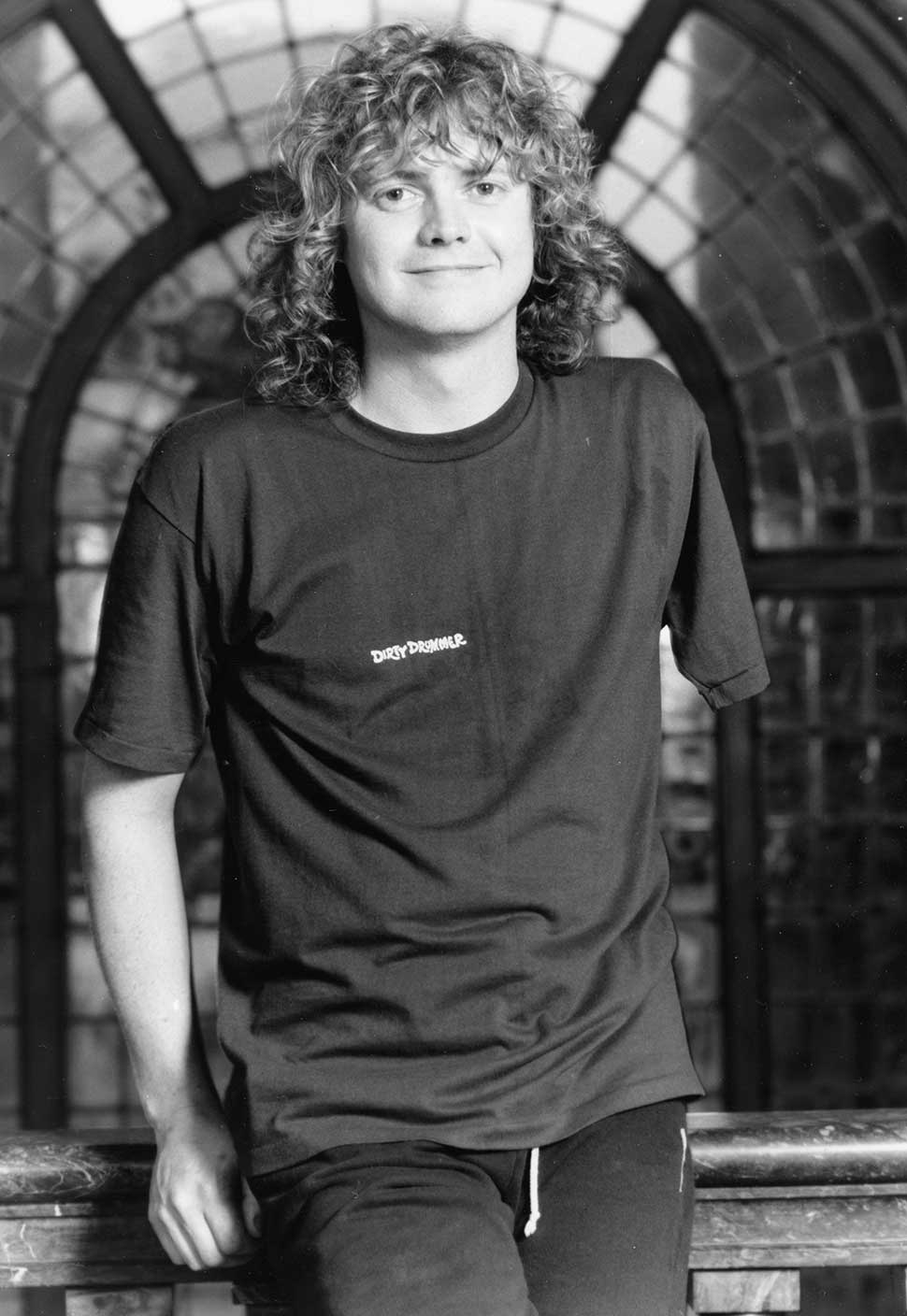

To say they were worried would be an understatement. The pressures of success come from all directions – fans, management, your label, all need whatever you do next to be better than what you did last. But no one can tell you how to achieve that. Waking up after another drunken night in the city, drummer Rick Allen observed: “This is hysteria!” And, boom, they were off…

“We were scared,” singer Joe Elliott recounts. “We had absolutely nothing in the way of ideas. We’d learned we couldn’t write on the road; you were doing all these shows and interviews and appearances. If you managed to get an idea down, you were proud of the achievement rather than asking yourself whether it was a good idea. Playing it back months later you’d wonder where your head had been. Besides, we’d enjoyed Pyromania so much, and we’d been living with that for nearly two years. We had nothing to go on. But we knew the knives would be out.”

If you’re a band like Def Leppard, you already have a lot of the machinery in place. You know about constructing a song, you know about presenting drama and contrast, you know how to pitch the lyrics to give your audience the entertainment they’re looking for. But, again, the caveat this time is that it’s got to be double-perfect, bang on the button.

Fortunately, they had Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange on board, the producer who had got so much out of them in their two previous studio epics, High’n’Dry and Pyromania. In classic ‘sixth member’ mode, Lange had already become part of the organisation and was happy to work on co-writing. “A lot of bands don’t let the producer in,” he commented. “Def Leppard let me right in.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Elliott is in no doubt of Lange’s value to Leppard: “He taught us so much. He taught us not to steal from one genre, but to steal from as many genres as possible – that’s how you make something unique.”

“Mutt said: ‘Let’s make a rock version of Thriller – an album you can have seven singles off,’” guitarist Phil Collen said in 2002. “And we did. It was amazing. It was his idea. He made us better than we were.”

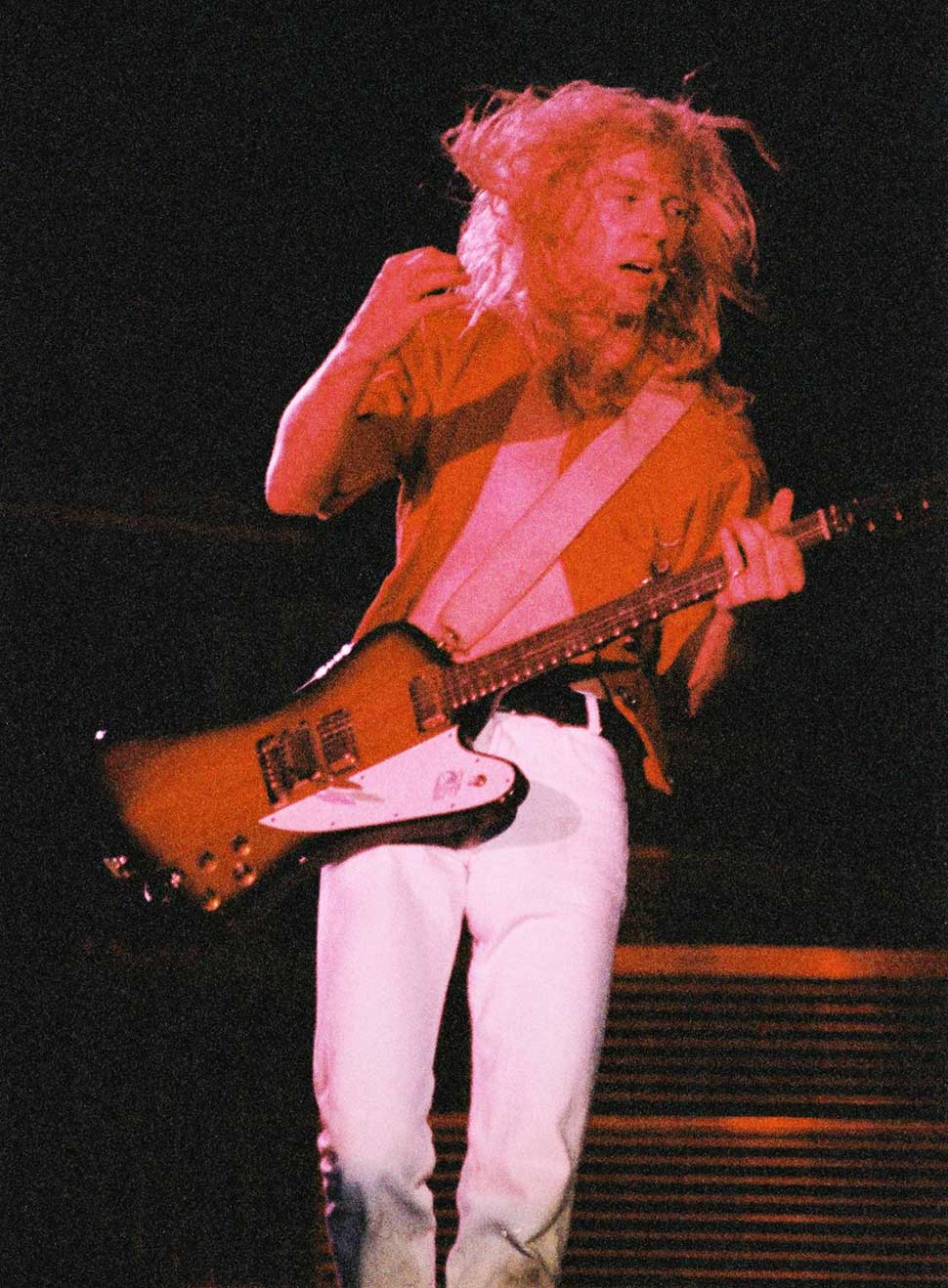

And so the album that would be Hysteria began taking shape. The first song to be written to anything like completion was Animal. And it set out the band’s stall big-time. Guitarists Collen and Steve Clark demolished the concept of the big riff, replacing the solid rock face with a complex construction of fine brickwork.

The idea was to tear the song wide open and explore the space within, but still wind up delivering a whopping punch of sound. In the same way that all matter is 99 per cent space (That’s correct – Science Ed.), thus it was with Animal. At the bottom end was a no-nonsense rhythm provided by bassist Rick Savage and drummer Allen; and at the top, Elliott’s trademark croak-scream vocals. There’s a clutch of cunningly constructed riffs, a crowd-pleasing singalong bit (complete with ‘wo-oah’s), and some controlled tension.

As soon as the management and label heard Animal, they knew everything was going to be okay. How wrong they were.

With a stack of songs in their pocket, the band moved to Hilversum, Holland, in August to begin the recording. Which is where the first kick in the nuts took the wind out of them: Mutt Lange had just completed work on The Cars’ Heartbeat City, and was forced to decide that he was too emotionally exhausted to work on Def Leppard’s album.

Rick was a guy overcoming a full-blown tragedy. It’s a great human story of a person overcoming a terrible situation

Phil Collen

Management attempted a coup by putting Jim Steinman in the producer’s chair. The thinking seemed to go like this: Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell was a classic album, and Hysteria is going to be one too, so surely Steinman can do what’s needed? But as Elliott pointed out at the time, Steinman was more of a writer than a producer.

The partnership never really took off. The band were poles apart from Steinman, who was more interested in catching the mood and feel of a take than in carefully building the perfect mix. Collen recalled a moment when Steinman said: “It’s a take,” and all they’d been doing was checking their tuning. “I’d warned them Jim Steinman was a writer,” Elliott says. “Bat Out Of Hell was produced by Todd Rundgren, so why would we want Jim Steinman?

“His work ethic was all wrong. We’d turn up at the studio at 11, and after the coffee we’d want to get started. He would come in at half-past-two, then tell Phil to play something more ‘oily’. Phil was saying: ‘What the hell do you mean?’ Then when he finished with us at 11 he went away and started writing for Bat Out Of Hell II.

"We were trying to be very focused, and he was sleeping in because he was thinking about Meat Loaf’s next album. We were paying him not to turn up. Then when he tried to have the carpet changed because he didn’t like the colour, that was the end of it. It was always going to happen.”

With eight tracks in various stages of construction, the band’s management were forced to conclude that things hadn’t worked out. At great expense they bought Steinman out of his contract, and the work done was scrapped.

Lange suggested they bring in Nigel Green, who had engineered Leppard’s previous two albums, So, working alongside Green the band started down the ‘self-produced’ trail.

The year of Big Brother had been a year of big bother. And then, with its last breath, it it kicked Def Leppard in the nuts again – but this time so much harder. On New Year’s Eve, Rick Allen crashed his car in Yorkshire, and in the accident his left arm was torn off. It was a cruel blow for anyone, let alone a musician. But with the kind of time the band had been experiencing, there must have been question marks over everyone’s heads, despite the band’s insistence ever since that no thought of quitting or getting a new drummer entered their heads.

With true Yorkshire grit, Allen was up and about in a matter of weeks, working with pioneering electronic drum makers Simmons to create a kit that could be played with two feet and one arm.

“I became a different person after the accident,” Allen said in 2004. “I was spiritually transformed. But there was an integration period that was very difficult. I had to grow into my new body and get my head around myself.

Rick Savage recalled: “The initial reaction was horror. It was possible he wouldn’t survive. But once he was off the danger list we began to come to terms with it.”

With Leppard holed up in in Wisselloord Studios in Holland, the days passed, with Allen re-learning to play in one room, and the band continuing work on Hysteria in another room. When he called them in to hear him playing a Led Zeppelin track, they knew he was going to fight it out.

“It ended up such a positive thing,” Collen said. “Rick was a guy overcoming a full-blown tragedy. It’s a great human story of a person overcoming a terrible situation.”

Just as concerns about Allen dissolved, though, another problem presented itself. Strange as it may seem, great songs do not necessarily make a great album. Elliott recalled: “We knew we had the songs, and we knew what we needed them to sound like, but we just couldn’t do it. We were all trying to second-guess Mutt.”

After further weeks of struggling through recording sessions, attempting to imitate their missing producer, Lange finally felt able to return to work, and committed to Hysteria. And then – as if to confirm that bad things really do come in threes – they had to scrap all the recordings again.

“Binning all that work… It’s not something we could do again,” Elliott says, almost shuddering at the memory. “It was Mutt’s encouragement that helped us do that. The thing is, it wasn’t terrible. What we’d done was good enough – as good as Pyromania – but Mutt said: ‘Why do Pyromania 2? That was a leap from High’n’Dry, now we have to make a leap from Pyromania.’ We were thinking: ‘Can we do this?’ It turned out we could.”

At long last, it seemed as if things were starting to happen. 16 months of work had been canned, but now it was time to clean up the mess, start again and come up with the goods. The challenge was steep: Pyromania had sold six million; Hysteria would now need to sell five million just to break even. Bean-counters shivered as the band attempted to refocus, forget the bad karma, and try to be brilliant.

When Lange spoke, they listened. Instead of using big amps they used Rockmans, small Walkman-like machines that generated a sound you could control to the nth degree. They began exploring multi-layered vocal effects, and experimenting with samplers so primitive they had to be triggered manually. Slowly but surely, things began to come together.

Lange’s approach to the album involved finding a some kind of production ‘hook’ for every song. Rocket came together when Elliott heard a recording of tribal drums, and was so inspired by the idea he stole the tape, looped it and built a song around it. The lyrics were a stream-of-consciousness concept, name-checking all the things he’d grown up with from Ziggy Stardust to Gary Glitter.

Love Bites was a song Lange had written, based on his country influences, but exposed to Leppard’s full balladeering barrage. The cunning addition of little squeaks and breaths, which Elliott refers to as “Simon Le Bon bits” added an extra dimension of character which lifted the track just above the ordinary. The abandonment of a set of backing vocals – insisting they understood what he was trying to achieve but it just wasn’t them – was the one and only time the band vetoed any of Lange’s ideas.

Gods Of War was based on the opening riff created by Steve Clark. It was one of his off-the-wall ideas which only a band of Def Lep’s persuasion could really grab onto and make work – and they did. Clark, who died in 1991 of alcohol-related complications, was a master live artist who found Heaven on stage and Hell in the studio. He can’t have had a great time recording Hysteria, but he still gave it his all. In another departure from the norm, Elliott’s lyrics reflected bewilderment at the world leaders who ran the Cold War for their own ends, leaving us mortals to suffer the consequences.

As work moved towards the completion of 11 tracks, Lange was convinced they still didn’t have an album – there was still something missing. With the budget bust, the money men panicking and the band exhausted, no one agreed with him. Until one day, during a break, Elliott picked up a guitar and played a few notes of an idea he’d had.

“I was just farting around,” Elliott explains, “when Mutt came back from the toilet, or wherever, and he said: ‘What the hell are you playing? That’s the best hook I’ve heard in five years!”

They worked it up a bit into what became Pour Some Sugar On Me, and then faced the job of convincing the band that they had to record this one more track. “I knew there was going to be a problem with the guys,” Elliott says. “I was into it because Mutt and I had put it together, but everyone else was staggering over the finish line. No one wanted to face another track. I remember seeing their faces when we said: ‘One more to go, guys.’ Steve put his hands over his face and went: ‘Oh no…’ But when we played it to them they realised how little needed doing to it, so we got away with it.

“That was the only time anyone thought, we can’t go on, we have to stop. But it turned out to be the most important song on the record.”

By early 1986 Def Leppard were stretched to their emotional limits, and decided they needed to get out of the studio. They booked a number of low-key shows in Ireland, leading up to some European festival dates over the summer. They also booked an additional drummer, Jeff Rich, who at the time was with Status Quo. The idea was to support Allen, in case for any reason he couldn’t keep it together – a thought that must have loomed large.

And it went to plan – until Rich didn’t make it to one of Leppard’s shows. It wasn’t his fault: the Leppard shows had to be booked to coincide with Quo’s days off, and flying from Britain to Ireland every day was bound to come unstuck eventually. It did so when the band played in Ballybunion; Rich arrived 40 minutes into the set and joined the show late. But by then Allen’s confidence had a huge boost when he realised he could hold the show on his own. So the following night Rich was in the audience just in case, and Allen drummed alone. And did he brilliantly.

In a very cloud-and-silver-lining way, Elliott observed that Allen’s re-learning of his trade really had paid off for the band. It meant Allen had had to abandon some of his fills, and inventing new ones, and as he built up his new technique around the Hysteria production he was able to play exactly what the album needed.

If the world needed any further evidence that Def Leppard were back in business, it was presented at the Monsters Of Rock festival at Castle Donington on August 16 that year. No one wanted any kind of sympathy vote, so the plan was to ignore Allen’s missing arm for performance purposes. But Elliott recalls the feeling in the audience was so warm, so genuinely sympathetic, that something had to be said. “Ladies and gentlemen – Rick Allen,” was it. And the crowd went wild. After that trip, finishing the album off felt a lot easier.

“We were back.” Elliott says. “It gave us so much confidence. When we went back to the studio we were different men. Finishing an album is the hardest part, but that gave us the energy we needed to see it through.”

Mutt Lange took five months to mix Hysteria, most of that time spent setting the mood. And there was one more ball-breaking kick for Leppard when he had to spend three weeks in hospital with a leg injury. Finally, in early 1987, the album was finished: in the end a dozen tracks instead of the usual 10, with a lot of good songs having fallen along the wayside.

“We’d had the original 10 songs,” Rick Savage recalled, “but we were writing new ones all the time. The amount of time we spent on that album meant things kept going out of date, and this was a way of keeping it fresh. But it got to the stage where we had 12 songs and nobody wanted to throw another two out. So we thought we’ll give them two more tracks than normal – gives people a bit better value for money.”

Everyone held their breath as the release date was announced for August – 43 months, almost five years, after the project had begun. Futures and careers were now riding on how many copies Hysteria would sell. The target could be no less than six million.

Animal was the first single (Women in the US), and it gave the band their first UK hit – an extremely positive sign. Over the following months another five tracks were released as singles as the band headed out on tour, performing in the famous ‘in the round’ format (which required them to be taken from the dressing room to the stage, through the audience, in laundry carts).

Where fate had been throwing punches at Def Leppard it was now smiling on them (and maybe even throwing them a kiss or two). Sales of the album faltered, then stalled at around five million (which for just about any other band would have been a success). But then strip club dancers started using Pour Some Sugar On Me as their backing track, and word of mouth led to rotation play on radio stations across the United States. Suddenly the album was shifting tens of thousands a day. In the end it sold 16 million copies.

If any one track summarises the Def Leppard philosophy, it must be Pour Some Sugar… It’s simple, it’s anthemic, it acknowledges inspiration from a range of sources, and the lyrics are tongue-in-cheek, entertaining and upbeat. It’s in the spirit of I Love Rock’n’Roll but is much more than that, with the careful blend of guitars, layered vocals, strong melody and shouty bits. And if Elliott’s raspier-than-usual voice makes it sound like it hurt to sing like that, it’s because it did.

“One of the reasons it took so long to finish the album was our approach to production,” Savage reflected in 2002. “The way we produced it started a new wave of recording technology. You can now do in an afternoon what took us three months with Hysteria.”

“It’s incredible to think how fast everything’s become,” Elliott says. “When we put the reverse vocals on Gods Of War, you physically had to take the tape off the reel, put it on backwards, record it to another reel, then put the tape back again. Now you just select the section you want to reverse and press ‘reverse’. You couldn’t go back to that way of working.”

Elliott was once asked if he felt the album was, in fact, over-produced. Predictably, he didn’t: “It’s big production, though. It’s huge. It’s using the studio to your benefit; you don’t just go in and play live then master the tapes, you have to create. That’s what we did.”

Almost 20 years after its release, Elliott has been interviewed about Hysteria a countless times (he describes it as a drawer in his mind which he opens when he’s in the mood but would rather ignore at other times).

“If one word sums the whole experience up, it would be ‘determination’,” he says. “We were still young – I was 24, Rick was 20. We could deal with things like that. But you couldn’t again – Pink Floyd have always said there could never be a The Wall 2. There could never be a Hysteria 2.”

Hysteria did everything that was expected of it and more. It took more time and energy from the band than anyone could have thought possible, but gave as much back. Elliott summed up both the secret to creating a classic album and the result of achieving one when he said: “We crossed over without selling out. We set out to be the biggest band in the world. And for a short while we were.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock #91.

Not only is one-time online news editor Martin an established rock journalist and drummer, but he’s also penned several books on music history, including SAHB Story: The Tale of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, a band he once managed, and the best-selling Apollo Memories about the history of the legendary and infamous Glasgow Apollo. Martin has written for Classic Rock and Prog and at one time had written more articles for Louder than anyone else (we think he's second now). He’s appeared on TV and when not delving intro all things music, can be found travelling along the UK’s vast canal network.