Preposterous, Excessive & Egotistical. Musical, Challenging & Dynamic. Emerson, Lake & Palmer. No other band in the history of prog rock had engendered such extreme reactions as ELP. In fact, they’ve come to embody the best and worst of the genre – depending on your viewpoint.

The first true ‘supergroup’ of prog, this was a coming together of three established talents, a trio of individuals who couldn’t even agree on a band name; even Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton settled on Cream.

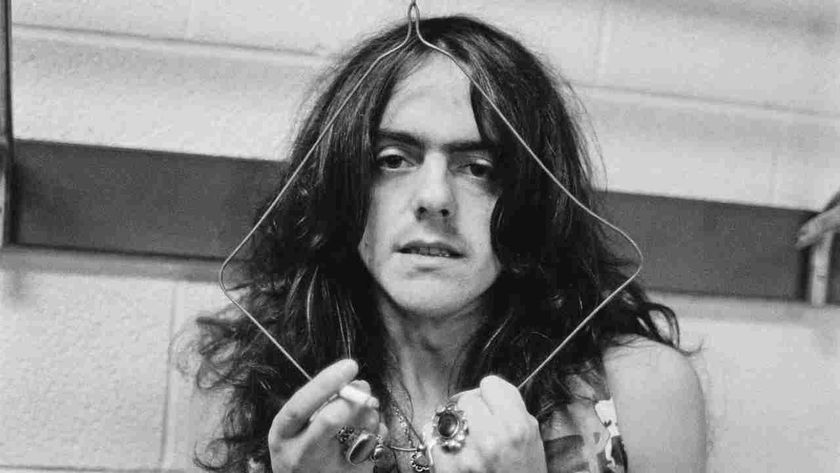

“In the end, we had to go for our own names,” keyboard master Keith Emerson once said. “But that caused problems. In what order should names appear? What we had was alphabetical, but you try telling Greg Lake and Carl Palmer that!”

From taking a 58-piece orchestra on the road in America during 1977 to Lake’s infamous Persian rug, this band led the way when it came to doing things in the most ridiculously overblown manner. But, on the other hand, they also created some of the most inspiring music of the 1970s.

However, when you think about it, there’s an obvious reason why there was constant tension and strain between the three – all of them were personalities and leaders in their own right. Nobody in the band could act as a conduit and sounding board for the others. There were no side men. It might have been different had Emerson and Lake secured Mitch Mitchell, their first choice drummer (ELM?); he was used to playing second fiddle in the Jimi Hendrix Experience. And he could even have been the catalyst in persuading Hendrix himself to join the band (HELM?), as was once strongly mooted.

The story of most successful bands dictates that, without a low-key member, there’s an imbalance – and ELP were definitely not a balanced triangle.

Emerson gave a clue to his understanding of what was missing when he said: “I’m the sort of guy that likes to go on stage with a whole band. They’re all around and once you get warmed up and you’re playing for the audience, I don’t mind if they leave the stage for me to do a couple of piano solos. But to walk onto a stage straight off, it concerns me somewhat.”

However, despite all their problems, the fact remains that there was – still is, probably – an underlying, albeit grudging respect between Emerson, Lake & Palmer. And this has actually shown itself to be the case in a myriad of subsequent projects, each of which has involved two of the three. Every possible permutation has occurred.

Consider the pressure that ELP were under when they first got together 40 years ago. Unlike Yes, Genesis or Pink Floyd – all of whom developed organically – this band was expected to be supercharged and successful from the start – it was, after all, a union of high profile musicians. So, in many respects, anything achieved by ELP was under the most intense of spotlights.

The same might be said of the decision to bring Greg Lake into Asia during late 1983, thereby re-uniting him with Palmer. Themselves a ‘supergroup’, Asia had parted with vocalist/bassist John Wetton after the release of second album Alpha. Whether he was pushed or jumped is irrelevant here, but Lake was brought in to join Palmer, guitarist Steve Howe and keyboard player Geoff Downes for the Asia In Asia show at the famed Budokan in Tokyo on December 6, 1983. This was the first gig ever to be simulcast by MTV via satellite to the US – but the show itself wasn’t a huge success, to say the least.

Lake’s voice simply wasn’t suited to the songs, many of which had to undergo a key change. He was also reading the lyrics from a teleprompter – something that was obvious to everyone.

It was no surprise that the bassist/vocalist quit early in ’84, with Wetton returning. But did he ever really stand a chance? So, the first reunion of ‘Two From Three’ (as it were) wasn’t so much a failure as something which was never given the opportunity to truly develop.

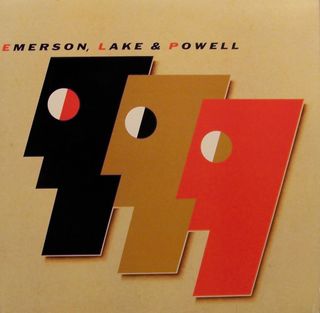

In 1985, it was Emerson and Lake’s turn to team. When Palmer declined to join a full-blown reunion (preferring to stay with Asia), there was an initial attempt to get Bill Bruford, but he was committed to both King Crimson and his own band, Earthworks, so the pair then turned to Cozy Powell – Emerson, Lake & Powell!

“Cozy was a very old friend of mine,” said Emerson. “He called up and said, ‘If you need a drummer, I’d love to do it’. So Cozy came down to my studio and we started working on this album. And then we realised, ‘Oh my goodness, you have the same initials, it’s ELP again!’.”

The trio’s subsequent self-titled album, released in 1986, was actually quite a success, even generating the hit single Touch & Go, as well as featuring a cover of 60s hit The Loco-Motion (shades of Nutrocker revisited?) and the classic piece Mars, The Bringer Of War. And the balance within the band worked well. Unlike Palmer, Powell had a background that allowed him to be a sounding board. He was prepared to underplay his role to bring out the best in the others.

“I’d worked with Ritchie Blackmore, David Coverdale and Michael Schenker,” Powell said of his time with this version of ELP, “so I was used to dealing with those sort of people. After them, Keith and Greg were almost a dream.”

Sadly, there was no second album from the band, but this was down to finances, rather than any inherent problems between the three members.

“By the time it came to making a second album, there wasn’t any money left,” Emerson has admitted. “Greg said, ‘Well, if there isn’t any money left, and PolyGram [the band’s label] isn’t interested in putting any more money up, I’m not interested’. And, of course, Cozy was being offered jobs and he got fed up with the indecisions and said, ‘I’m leaving’.”

Amazingly, Palmer was delighted to see Emerson, Lake & Powell out there working, because it gave him the chance to get Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s back catalogue re-activated (by now the drummer had almost taken over protecting the trio’s heritage):

“If they hadn’t gone out with Cozy Powell, I couldn’t have gotten the record company to spend the amount of money on the back catalogue that they spent. I’d already made 16 albums which Cozy was promoting for me and the band, so it was a much better thing for them go out with him than to not go out at all.”

Unlike the situation with Lake and Palmer in Asia, at least this time around the pairing had managed to record. But even so, there was still a feeling of unfinished business.

Next on the list were Emerson and Palmer. In 1988 they got together with American Robert Berry to form 3, releasing one album, To The Power Of Three. But this was to be another short-lived liaison. The record was heavily criticised for being too bland and commercial, although Emerson launched a staunch defence of the project at the time: ”If people want ELP, then they can check out what we’ve done before. It’s all there. This isn’t supposed to be a rehash of the past, but something all three of us want to do right now. Is it bland? Well, if you want to consider well-crafted songs that way, then fine. To me, Carl and I are being very creative, and Robert’s the right man to be involved. He’s contributed a lot to 3.”

However, 3 seemed doomed when they played at the Atlantic Records 40th anniversary show in 1988, billed as‘Emerson And Palmer’ (3 were signed to Geffen, hence the reason that the band themselves weren’t credited). All they did were covers of America, Fanfare For The Common Man and Dave Brubeck’s Blue Rondo À La Turk. Even a subsequent tour from 3 failed to take them further, despite decent reactions. Once again, it appeared that even pairing two from the three of ELP couldn’t quite cut it. There was always something missing.

Of course, the three had each pursued their own solo projects during the intervening years, with moderate success.

But, perhaps it was Lake who summed up the band’s dilemma best: “After a lifetime of being in high profile bands, all of a sudden there is a feeling of disorientation. Interestingly enough there are very few people who’ve come out of successful bands who’ve really sustained solo careers. It is a very difficult thing to do. I’m not quite sure why that is, whether it’s because of their previous identity, or simply because the artist in question just feels that greater degree of discrimination.”

So, there was perhaps an inevitability about the decision to reunite the three-piece in 1992, for the Black Moon album and a highly successful tour. But the initial enthusiasm soon waned. In 1994, they released the hugely disappointing In The Hot Seat, and over the next few years, interest in the band seemed to be on the wane, leading the decision to call it quits again in 1998, amidst more arguing. Emerson publicly berated Lake for not rehearsing enough, Lake moaned that he wanted to produce the band’s next record…

Palmer merely stated, “I thought the albums we made [Black Moon and In The Hot Seat] were rubbish. Every band has its day, and possibly from a creative point, we might have had our day.”

Since then, there’s been no attempt from any of the three to work with each other. It’s as if they’ve learnt the lesson of the previous 30 years: their overpowering personalities and overwhelming sense of self-importance (however justified) inevitably has to be destructive for any projects involving two or more of ELP. Perhaps Palmer gave a decent insight into the psychological mechanics of the three when he said: “Yes, we were pompous – we’re English! You have to be pompous. We came from Great Britain. We weren’t a blues band. We weren’t a rock band. We played classical adaptations similar to what I do now. We played folk tunes, we were quite eclectic. We dealt with technology, we didn’t have a guitar player, and we never played 12-bar. We were pomp because that’s where we come from. We’re not from the South, or from Mississippi – we’re English!”

If, as is being heavily rumoured there’s to be a 40th anniversary tour, one can only hope it lasts long enough for the trio to celebrate the positives of their union, yet ends before old problems are resurrected. From ELP to Asia, Emerson, Lake & Powell to 3, one thing is certain – ultimately, these are three highly gifted men with the capacity to behave like spoilt brats in each other’s company.

This article originally featured in issue 1 of Prog Magazine.