"So go away away, leave me alone, don’t bother me…"

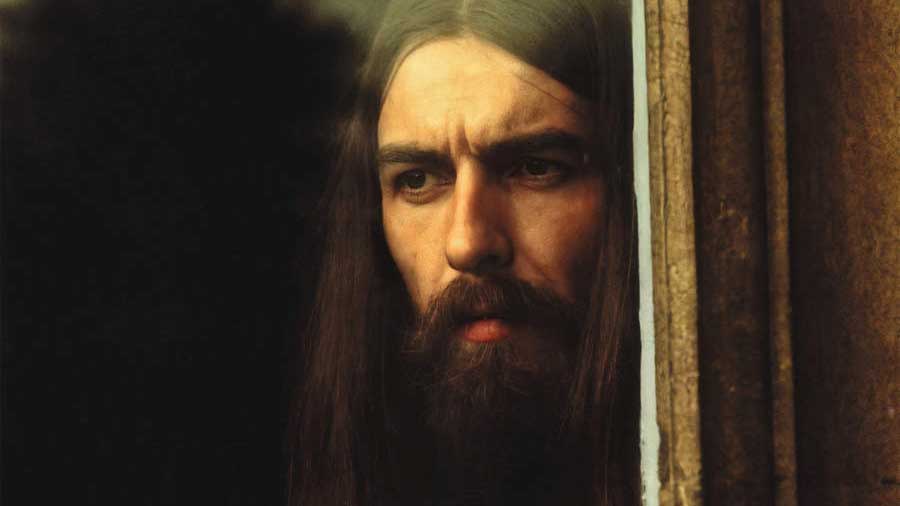

Those words, from Don’t Bother Me, a glum kiss-off to an lover, which appeared on The Beatles’ 1963 album With The Beatles, mark George Harrison’s first recorded entry as a songwriter. It wasn’t of any significant artistic weight that would rattle the axis of the golden Lennon/ McCartney team, nor would it hint at the glory and sophistication that would be his masterpiece solo record.

Flash forward more than half a century later, and Harrison’s landmark All Things Must Pass album is not only considered perhaps the greatest solo record by a Beatle, but is also routinely selected in the music press as among the most important rock albums of all time.

Relegated to second fiddle status with The Beatles, initially content with his role of laying down inventive guitar lines and vocal harmonies and contributing the occasional song, as the years rolled by Harrison’s confidence grew and his craft sharpened; songs like I Need You, Taxman, I Want To Tell You, Within You, Without You and It’s All Too Much displayed a unique artistic flair and singular musical personality.

From there his continued growth as a songwriter bore rich fruit; witness White Album jewels While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Savoy Truffle and Piggies, B-sides The Inner Light and Old Brown Shoe, and his stellar contributions to Abbey Road: Something and Here Comes The Sun, arguably the best songs on The Beatles’ swansong album.

In the shadow of the Beatles’ breakup, Harrison’s songwriting was blossoming. Having been limited to one or two songs per album, he began stockpiling them during the latter years of The Beatles’ career, with a few auditioned during the Let It Be sessions (namely All Things Must Pass, Let It Down, Isn’t It A Pity and Wah-Wah).

“I was probably trying to get them recorded in amongst all the usual John [Lennon] and Paul [McCartney] stuff,” Harrison recalled in a 2000 interview with Billboard. “For me, that was the great thing about splitting up: to be able to go off and make my own record and record all these songs that I’d been stockpiling. And also to be able to record with all these new people, which was like a breath of fresh air, really.

“Imagine if the Beatles had gone on and on. Well, the songs on All Things Must Pass, maybe some of them I would probably only just got around to do now, you know, with my quota that I was allowed [laughs]. Isn’t It A Pity would just have been a Beatles song, wouldn’t it? And now that could be said for each one of us. Imagine would have been a Beatles song, but it was with John’s songs. It just happened that The Beatles finished.”

Released in late November 1970, All Things Must Pass was co-produced by Harrison and Phil Spector. “Phil Spector was probably the greatest producer from the sixties, and it was good to work with him because I needed some assistance in the control box,” Harrison explain in a 2001 interview with Yahoo.

The album featured a Who’s Who of the music world – guitarists Eric Clapton, Peter Frampton, Dave Mason and members of Badfinger, keyboard players Gary Wright, Billy Preston and Bobby Whitlock, bassists Klaus Voormann and Carl Radle, drummers Ringo Starr, Jim Gordon, Alan White and Ginger Baker, and a host of others.

George Harrison (interview with Howard Smith, 1970): I’d much rather play with other people because… united we stand, divided we fall. I think musically it can sound much more together if you have a bass player, a drummer and, you know, a few friends. A little help from your friends. I really want to use as much instrumentation as I think the songs need.

Bobby Whitlock (keyboards): I was fortunate to hear a lot of George’s songs earmarked for the album before we recorded it, things like My Sweet Lord, Awaiting On You All and Run Of The Mill. Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, Eric Clapton and myself, we had played together before [as Derek & The Dominos], so we were already dialled in with each other as musicians.

So when it came to us being the core band on All Things Must Pass, you couldn’t have asked for better support, because we were already linked up together in a special musical way. We didn’t have to think about our role or our place in whatever we were playing, because that came real naturally, right down to Eric and me singing some background parts.

Grandiose and ambitious, spiritual and heartfelt, All Things Must Pass was a tour de force. The album’s lyrical themes of spirituality, death, redemption and angst resonated strongly, while its sound was huge and expansive.

Harrison (interview with DJ Chris Carter, 2001): In those days it was like the reverb was kind of used a bit more than what I would do now. But at the time I did the record with Phil Spector, and we did it like Phil Spector would do it. It’s hard to go back to anything thirty years later and expect it to be how you would want it now. That’s the only thing about the production, it was done in cinemascope and it had a lot of reverb on it, but that’s how it was and at that time I really liked it.

Whitlock: Some of that heavy reverb went down on the tape while we were cutting, so it was difficult for George to take it off. But for me it gives it that signature ‘Wall of Sound’. I don’t have any problem with it; I love it the way the original sounds.

I mean, when you have all those musicians playing at once it creates a ‘wall of sound’, and all Spector had to do was add some hall echo and reverb. That gave it Spector’s signature sound. I don’t think George regretted it until everybody got to talking about it, and by then it made him think there might have been too much reverb, but it’s too late.

Opening with the gentle I’d Have You Anytime, a co-write with Bob Dylan, the record spins through a dazzling array of styles: rock (Wah Wah), gospel (Awaiting On You All, Hear Me Lord), R&B (What Is Life), country (Behind That Locked Door) and pastoral folk.

The album’s first single, My Sweet Lord, was a No.1 smash around the world, setting the stage for Harrison’s arrival as a solo artist, both critically and commercially.

“I was at our kitchen table when George wrote My Sweet Lord, recalled his then wife Patti Boyd. “I remember it very, very clearly. It’s a beautiful song and he was so proud of it. It was absolutely stunning. I know he wrote it; he didn’t copy it from The Chiffons. It was deeply upsetting and really hurtful when he was called into court in America for supposedly plagiarising one of The Chiffons’ songs.

"That song became a bit tainted when we were told he’d have to go to court and defend himself with his guitar. George stopped listening to the radio after that so he wouldn’t be influenced by any music. There was no possibility of anything else influencing him when he wrote songs."

Harrison (interview, 1971): As far as I’m concerned, My Sweet Lord was a hit because of the sound and its simplicity. The sound of that record, it sounds like one huge guitar. The way Phil Spector and I put that down was we had two drummers, a bass player, two pianos and about five acoustic guitars, a tambourine player, and we sequenced it in order.

Everybody plays live in the studio. I spend a lot of time with the other rhythm guitar players to get them all to play exactly the same rhythm so it just sounded perfectly in sync. I overdubbed the voices, which I sang all the backup parts as well, and overdub the slide guitar, but everything else on it was live.

There’s Ringo and a drummer called Jim Gordon. Harrison’s slide playing lights up My Sweet Lord, but it was Dave Mason who unwittingly helped open the doors to slide guitar, a technique Harrison would master and which would become a trademark of his solo career.

Dave Mason (guitar): Delaney & Bonnie went to Europe to tour. We did a show at Fairfield Hall in Croydon and Eric [Clapton] and George came to the show. We were all backstage and, of course, they were asked to sit in, and George said: "Well, I don’t know any of these songs." I said: "There’s a song we do called Comin’ Home, and I play a little slide guitar part. Let me show you this little slide part goes".

And he came on stage and played that with us. Many years later George related this story to a writer and he credited me, saying: "Mason showed me this part and that’s what got me into starting to play slide guitar." Wow! And you can certainly hear George come into his own on slide guitar on All Things Must Pass. I’m quite proud and honoured to have sparked George’s interest to play slide guitar.

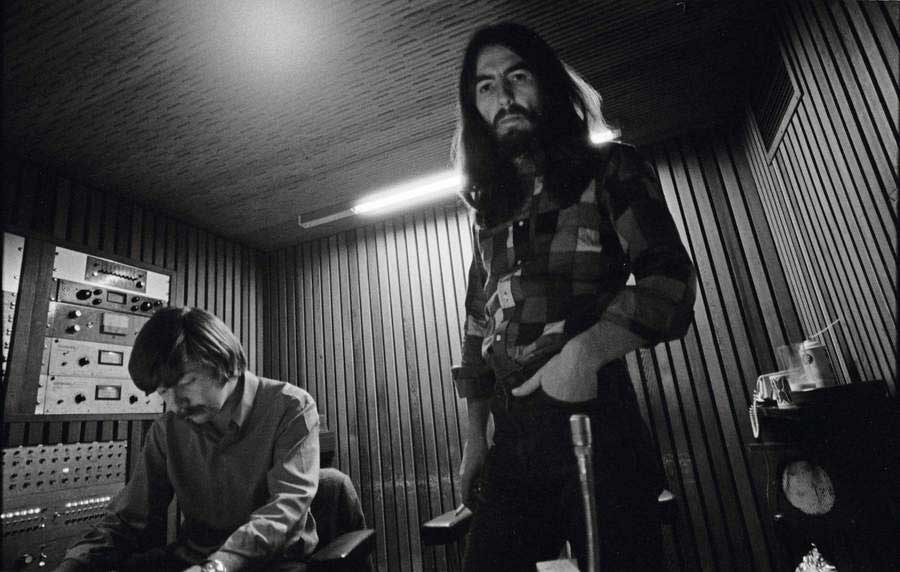

On May 28, 1970, at Abbey Road studios in St. John’s Wood, London, the All Things Must Pass sessions with a full band officially began.

Ken Scott (engineer): We started the All Things Must Pass sessions at Abbey Road. George was so comfortable at Abbey Road. Much as they might bitch about the place, they always came back to Abbey Road. Paul [McCartney] had his home studio built as an exact replica of Studio Two. There was obviously something about that studio that they all liked.

When it came time for All Things Must Pass, George recorded all the basic tracks there with a great engineer called Phil McDonald. Phil had been a second engineer for me for some time and then he moved up the ladder. We were swapping a lot of stuff around at that time. I’d record it and he’d mix it, I’d mix it and he’d record it. At Abbey Road there were still only eight-track machines.

Whitlock: George wouldn’t give you direction. He would just say: “Here’s the chords” and let you do your thing. Are you really going to tell people of the calibre of Ringo Starr, Eric [Clapton], Jim Gordon and myself what to play? No. We hear it. I know my part as soon as I hear something. He didn’t tell anybody what to play. But what he did do was come out with his acoustic guitar and he’d run through the song for the electric band and answer any questions. Then he would go down to where Badfinger were playing acoustic guitars and do the same thing.

Joey Molland (Badfinger, guitar): It was incredible to see all those rock stars in the studio and they’re all there ready to play. These were giants. Here was Eric Clapton working on his lead guitar bits, Klaus [Voormann] was really friendly. Billy Preston was super-friendly. It was very exciting but it was also very nervy. But we relaxed after George started talking and playing with us.

We had to learn the songs right away. He would only show it to us once or twice and then we’d run through it with the whole band. George gave us specific instructions and said: “Don’t play any fiddly bits,” keep it straight. He knew exactly what he wanted. We’d record two or three songs a day. On Beware Of Darkness and My Sweet Lord we played all the rhythm guitars. Phil [Spector] really wasn’t in charge, George was in charge. It was joyous time for all of us.

Alan White (drums): I played drums on about at least half of that album. It was a great experience. I was very young at the time and had just been through making Imagine with John [Lennon], which put me into a kind of Beatles circle. George kept coming down to sessions, and then he wanted me to be at all of the All Things Must Pass sessions. So for three weeks a whole bunch of us turned up at EMI Studios, and each day we’d start off and record a new song.

Harrison (interview, 1970): Wah-Wah was written during the Let It Be sessions. We had been away from each other after having a very difficult time recording the White Album, which went on for so long. I remember Paul and I were trying to have an argument and the crew carried on filming and recording. I couldn’t stand it. I decided: “This is it! I’m leaving!” Wah-Wah was a headache as well as a foot pedal. It was written during the time in the film [Let It Be] where John and Yoko were freaking out and screaming. I wrote this tune at home.

Whitlock: On Wah-Wah there was Ringo and Jim Gordon on drums, Carl Radle and Klaus Voormann on bass, Eric and George on guitars, me and Billy Preston on keyboards. It was a wise decision from George to have Billy and I play on that track because we both came from the same soul, R&B, gospel background.

Billy would play [Hammond] B-3 on Behind That Locked Door and I’d play the B-3 on the rest of the songs that needed it. We cut all the songs live with the band and then there would be some overdubs added later. I’d overdub hanging bells, tubular bells on songs like Hear Me Lord and The Art Of Dying.

We also recorded two Derek & The Dominos songs – Roll It Over and Tell The Truth – during the sessions. George and Eric were the guitar players on it, and that was part of the deal of us playing on George’s album that we could record some Dominos stuff during the sessions.

John Barham (orchestrator): Although George wanted to make sure that everything met his exacting high standards, he wasn’t dogmatic about how those standards were reached. If a musician was not comfortable with a particular approach, George would give him the freedom and encourage him to find another approach which worked for him. He didn’t want to control or dominate the musicians that he worked with, rather he wanted to help them express themselves.

Mason (guitar): We [Traffic] used to go down to the Sgt. Pepper sessions, and that’s when I first met George. While in The Beatles, George was living under the shadow of Lennon and McCartney for a long time, which is understandable. But All Things Must Pass was the album where George truly blossomed.

Peter Frampton (guitar): I have great memories of that record because playing with all those people, let alone working for a Beatle – or a couple of them, actually, because Ringo was always there. [Eric] Clapton would walk in and out. Gary Brooker, Gary Wright, Klaus Voormann. It was an incredible experience. I played on songs like If Not For You and Behind That Locked Door, all the ones that Pete Drake played on; he was a pedal steel player who came over from Nashville.

So I played on five or six of the basic tracks and then George called me and asked me to come back. [Imitates Harrison’s voice] “Phil wants more acoustics.” And I said: “You’re kidding me?” [laughs] So I went back to Abbey Road – I lived around the corner in St. John’s Wood. We did it in the big Sgt. Pepper studio. There I am sitting next to George with my acoustic. We’re both sitting on two stools with two mics that I’m sure The Beatles had all sung on. There’s Phil Spector in the booth. They’re just playing every track, one track after the other, and we’re just adding more acoustics.

I don’t know how many tracks I played on, but the majority [laughs]. It was quite amazing being on those sessions and hearing the acoustic sound that we got, which was incredible. I played on the record, and why I didn’t get credited at the time I have no idea. I never could ask George: “Mr. Beatle, you left me off” [laughs]. It was a big thing at the time, but it’s one of those things.

Harrison (Billboard, 2000): I think [Behind That Locked Door] was very much influenced by Bob [Dylan]’s Nashville Skyline [1969] period. I actually wrote that the night before the Isle of Wight Festival in [August] 1970.

Gary Wright (keyboards): I was very, very happy to play on that whole record. Klaus Voormann called me and said: “Hey, I’m in the studio with George and he’s doing his first solo album and Phil Spector’s producing and they want to have another piano player. Are you free?” And I said: “Absolutely.”

So I jumped into the car, and I’d never been to Abbey Road before so I think I got a little lost on the way there [laughs]. So I showed up and they’d already started. They had been rehearsing and just about ready to start recording. So I came in and was quickly and frantically trying to learn the song, which was Isn’t It A Pity. All of a sudden the control room microphone blasted out into the studio: “Who the heck is that on the piano making all those mistakes?!”

And that was Phil Spector. So George came up, and said: “Don’t worry, we have plenty of time. We have all the time in the world so take your time…” I thought what a nice guy he is. He was not really pushing me, and I could take my time to learn the song properly. I played Wurlitzer piano on that one.

Phil Spector’s trademark ‘Wall of Sound’, popularised on hit records by The Ronettes, the Righteous Brothers, The Crystals and Ike & Tina Turner, among others, coloured the sonic palette of All Things Must Pass, with songs like Isn’t It A Pity, Wah-Wah and the title track slathered in mountains of reverb.

Frampton: Spector was the co-producer with George. His philosophy was ‘more of everything’.

Molland: We were working on either Isn’t It A Pity or Wah-Wah, and went into the control room to have a listen to the track, and Spector was drunk and literally laying on the floor under the console. I’m not exaggerating, and I’m not saying this because it was a bad thing. Everybody thought it was perfectly normal [laughs].

Whitlock: The atmosphere of the All Things Must Pass sessions was peaceful and calm. It was joy and happiness. It was not a sombre occasion. It was a celebratory event but not in a party sense of the word. We were happy to be there and everyone was joyful and excited. Every time we recorded something, it was like: “Oh yeah, man, that’s great!”

Wright: While we were recording All Things Must Pass, in the studio George was burning incense and had these pictures strategically located of these Indian yogis and saints and I thought that was really cool. I’d never been in that kind of a vibe before. He saw that I was interested in it and kind of took me under his wing and started to tell me about Eastern philosophy and how we was into it. At that time he was into the Hari Krishna movement. He was chanting the Krishna mantra and I was just fascinated by it.

Harrison (interview, 1970): What Is Life was written for Billy Preston in 1969. I wrote it very quickly, fifteen or thirty minutes, on the way to Olympic Studio in London when I was producing one of his albums. I recorded What Is Life one way and didn’t like it. Then we worked on it a second time and I came up with a bass line, and then I got the feel to it and we re-recorded it and it came out much better.

Whitlock: I liked the guitar intro of What Is Life. I like the whole thing because it was so different. Eric played Leslie guitar on that one. Everything he did on the album was exactly right. Every note is exactly right. With the two LPs showcasing 17 original songs and one outside composition (Bob Dylan’s If Not For You), a third LP, dubbed Apple Jams, found the gang letting their hair down with five lengthy spontaneous jams.

Whitlock: The jams on the album were in a sense all of us saying hello to each other. I didn’t know anybody there, except for Eric, Dave Mason, George and Billy Preston, of course. Billy had played with us before with Delaney & Bonnie And Friends.

Scott: A vivid memory I have working on All Things Must Pass centres upon the volume we used to monitor the album. A particular neighbour got very upset one night, and tried to stop us by throwing a beer bottle through the glass windows in the mix room [laughs]. It just so happened that Phil Spector was closest to the window and he completely freaked out. We had to spend the next god-knows how long to calm him down. That was quite funny.

With songs like My Sweet Lord, Awaiting On You All, What Is Life and Hear Me Lord, there’s a thread of deep spirituality at the core of the record.

Scott: The album is very spiritual. There were some people who become exceedingly religious and try and force it down you, but George was never like that. He would discuss his thoughts on his religion and spirituality but he never foisted it on you, which was great.

Whitlock: George was definitely a perfectionist in the studio. I remember singing the second background part on My Sweet Lord; Eric didn’t show up. Then George added that whole big chorus of voices. ‘Hallelujah’, ‘Hari Krishna’, all these different connotations of the word ‘god’. I remember after he was done how wore out he was. He could hardly speak from singing parts over and over, stacking vocals in the chorus. It was pretty amazing.

Scott: A lot of the overdubs on the album were just him. For example all of the backing vocals. It would have been very easy to bring in six, eight singers and just have them do it, but George wanted to do it himself. It took an awful long time. Most people don’t realise it’s just George. I think it’s listed on the album as the George O’Hara Smith singers. People actually think that’s a group, but it was all George.

Whitlock: What makes it such a classic album fifty years later is the calibre of musicianship and the songs I believe is what bears the weight of it, and that invisible something, you know, whatever that is, and made that thing happen. You can’t see it, hear it, taste it, touch it or smell it, but you can feel it and it’s there. And suddenly fifty years later All Things Must Pass is still way up on the pedestal.

Scott: I think George was pleased at the freedom he had working on his own away from The Beatles. I think they all were by that time. It had been such a chaotic period. I know that George was always very unhappy that whenever his name was in the press it was always ‘ex-Beatle’. His whole thing was: “This had been only six years of my life, why am I always an ex-Beatle? I’ve had my successes on my own.”

Mason: What makes All Things Must Pass such a powerful statement is it’s a three-LP set with all this material. George was a super-generous in making this album including so many different people. I think part of it for him was still: ‘I’m emerging as the guy behind Lennon and McCartney for all this time, so some great backup wouldn’t hurt.’ But there was just so much material for a great solo album. It’s pure George all the way. They were great songs.

The 50th anniversary edition of All Things Must Pass is out now.