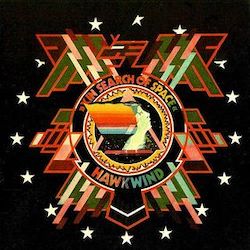

On October 8, 1971, Hawkwind released their second album, In Search Of Space. It’s a landmark record, space rock ground zero, and every bit as mind-melting and innovative as the then-contemporary krautrock scene in Germany.

But while Hawkwind were born out of the alternative society of Ladbroke Grove in west London, In Search Of Space wasn’t an album fuelled by peace and love. Instead, as its title suggests, it was a radical escape route from authoritarianism and mainstream conformity, and a blast of sonic disgust against the foolishness of the straight world.

The year of its creation was a tumultuous one for the band, with numerous altercations and brushes with death along the way. Yet by the end of 1971, Hawkwind would be the country’s biggest cult band with a newly minted science fiction mythology and a secret weapon in their arsenal set to propel them to even greater heights.

Hawkwind had ended 1970 by co-headlining the Christmas Space Party, a benefit gig at the Roundhouse for the underground press. Yet for bassist Thomas Crimble, it would prove to be his final show with the band. Crimble had played a key role in moving them on from the jammy, often abstract psychedelia of their self-titled debut album, and helped develop a more driving sound based around an increasingly dynamic rhythm section. But it had been decided that Dave Anderson, ex-Amon Düül II and more recently a member of Van der Graaf Generator, should replace him.

Although favourites of the Ladbroke Grove scene, Hawkwind were still building their profile outside of London, and the addition of Anderson gave them more than just a musical boost. He’d become friendly with Angela Finbow, the live booker at the band’s management company, Clearwater, and Anderson’s future wife. “I used to sit beside her in their office – every time the phone would ring, I’d say, ‘If they want a particular band, see if you can get Hawkwind as support!’” he remembers.

Yet as heralds of the counterculture, playing the provinces was often a perilous enterprise. After a gig at Manchester University in January, the band were assaulted in their dressing room and required medical treatment, while at the Malvern Winter Gardens in March 1971, they were forcibly ejected from the venue after giving away free copies of underground magazine Frendz, ‘subversive literature’ in the eyes of the local authorities. And the band got their first piece of national press when the Daily Mirror reported the fracas that ensued when teenage drummer Terry Ollis was caught playing naked at the Breaks Youth Centre in Hatfield.

A potential confrontation with The Man was always around the corner and would shape the lyrical content of their forthcoming album. As band co-founder Dave Brock says, “Guys with long hair were always getting picked up, always being searched in the street. Every time we arrived back in the early hours in our van, we’d be stopped by the police in Notting Hill and searched. In those days, anyone with long hair was a drug addict.”

But the siege mentality that Hawkwind developed also helped turn them into a tight-knit communal and musical unit. “That’s what brings a band together, constantly playing and travelling,” says Brock. “We toured and played nearly every day. We used to have our old yellow parcel van where we’d sit in our sleeping bags because we didn’t have a heater!”

This relentless touring schedule paid off, with the band building a significant fanbase around the country. “We used to pack out town halls, they just loved us,” says Ollis. “We were all out of our heads, and so was the audience! We really connected. We lived what we believed and practised what we preached.” Drugs were a major factor, of course, with saxophonist and frontman Nik Turner acquiring a large supply of liquid LSD, which he gave away to the audience: “I think it really compounded the band’s popularity, because people still come up to me and say, ‘Wow, that gig you did in 1971 changed my life!’ And I say, ‘You sure it wasn’t the acid?!’”

Prior to recording their second album, Hawkwind previewed some of their songs in a session for John Peel’s Top Gear show, broadcast in April 1971. Audibly, the months spent on the road had transformed the looser, trippier sound of before into a shockwave of concentrated, feral intensity.

It was also around this time that a number of important collaborators fell into Hawkwind’s orbit. Foremost of these was Robert Calvert, a friend of Turner’s from his hometown of Margate, who began to perform his space age poetry on stage with the band, and worked in the background with design genius Colin Fulcher, aka Barney Bubbles, on a fantastical sci-fi concept where the album became a two-dimensional spacecraft unmoored in time.

Calvert also introduced the band to Michael Moorcock, author and editor of ‘new wave’ science fiction magazine New Worlds, who memorably described Hawkwind as “barbarians with electronics”. Moorcock, too, began to perform with them at free gigs held under the concrete arches of the Westway, the newly erected flyover that runs through Ladbroke Grove. His first reading with the band was Sonic Attack, a public information parody that would increasingly define Hawkwind’s musical philosophy.

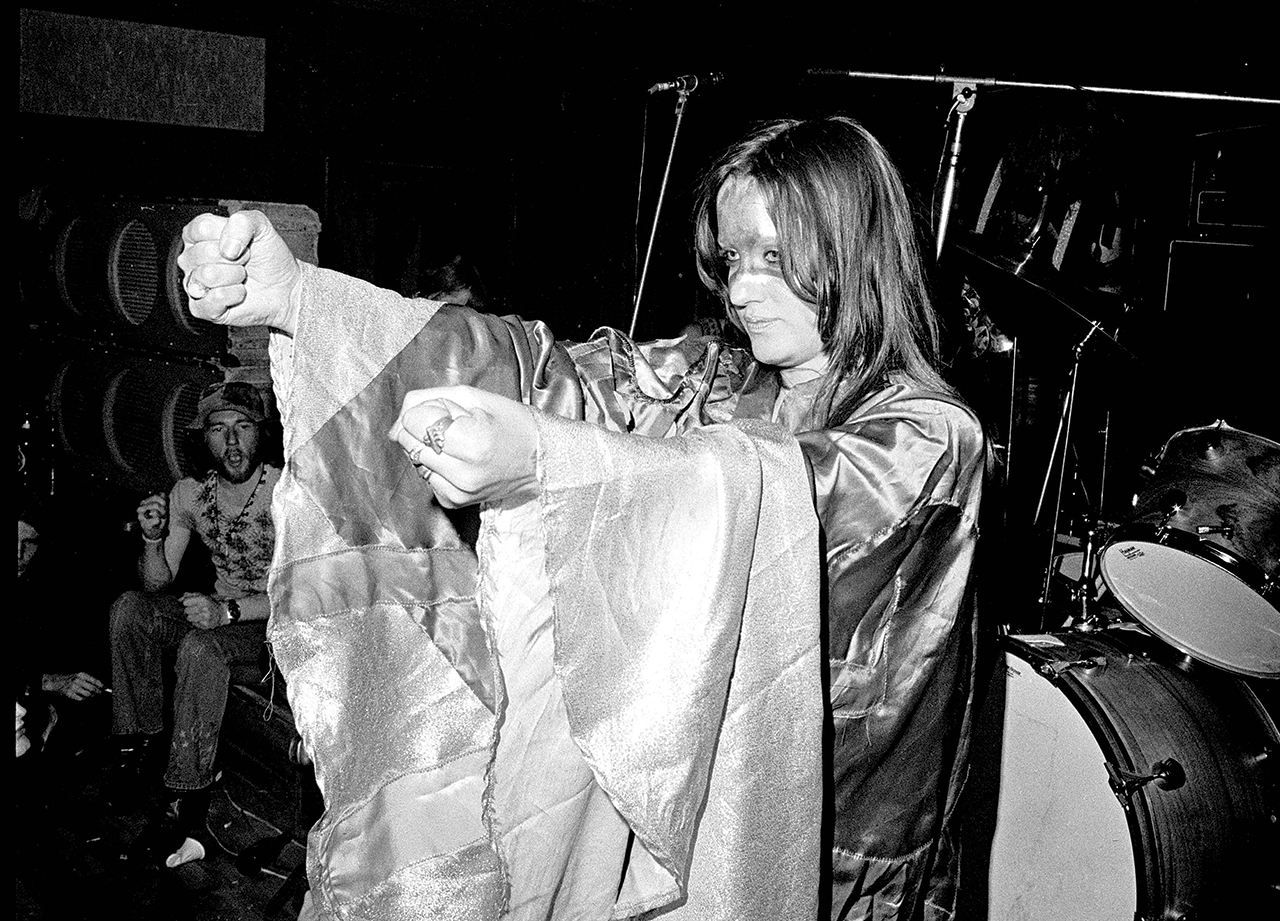

Yet the new addition to the band who made the greatest impact on stage was dancer Stacia Blake. She became a human lightning rod and focus for Hawkwind’s audio-visual onslaught after performing with them at a gig in Redruth, Cornwall. As she remembers, “I just said to Nik, ‘Can I get up and dance?’ And they made some silly remark like, ‘If you take your clothes off and paint your body’, something like that. I don’t think they expected me to do it, but I did! The feeling of total freedom is my overriding memory of that first appearance.”

The band travelled up to Aviemore in Scotland, where Anderson’s uncle owned a ski school, to rehearse ahead of the album’s recording. But disaster struck en route, as Turner recalls: “DikMik [Hawkwind’s electronics operator], two of the roadies and a couple of girls took a corner too fast, turning their van over. They hit a car, and the driver was killed. One of the roadies, John the Dump, had his arm sticking out of the window and when the van turned over, half his elbow was ground away.” To make matters worse, the man they’d killed turned out to be the nephew of the landlady where they were staying. Badly shaken, DikMik temporarily left the band to be replaced by road manager and soundman Del Dettmar.

But that wasn’t the last of their close encounters with death, as Ollis remembers: “On that same Scottish tour, Nik got electrocuted. Start of the gig, he went to do the introduction, but as soon as he got hold of the mic, he started shaking and fell to the floor. Del rushed out from behind the desk and booted the mic stand out of his hand. Nik went off to the hospital, and we did the gig, but he came back for the last number, his hands bandaged up, and managed to play the flute!”

The band began the recording of In Search Of Space at George Martin’s newly opened AIR Studios in London’s Oxford Street – except nothing happened. “We were there for a week, but we never even got the gear set up,” says Anderson. “The studio had suspension on the floor, so we spent the first day jumping up and down on that and running around like idiots! Then our friends the Furry Freak Brothers broke into George Martin’s office and pinched all his booze. They also spiked up the engineer, who got completely freaked out and never returned for the rest of the week.”

Decamping to Olympic Studios in Barnes, in south-west London, the recording of the album proper began under the watchful eye of experienced in-house engineer George Chkiantz, who had previously worked with Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin, and is often credited with inventing the stereo phasing technique known as flanging (as heard on the Small Faces’ Itchycoo Park). Chkiantz marshalled Hawkwind’s live-in-the-studio approach to produce a record that captures the band’s cosmic energy, but sounds a good deal more subtle and controlled than later releases.

The album begins with the 16-minute trance rock tour-de-force of You Shouldn’t Do That, a track with its origins in the extended jams the band had performed the previous year outside the fences of the Isle Of Wight Festival. It’s the song that defines Hawkwind’s unique brand of raw, pulsating space rock, hypnotic yet shot through with pure adrenaline, and has been both hugely influential and much copied over the years – but in 1971, there was no other band that sounded remotely like this in the UK.

Despite appearing to be skilfully arranged, You Shouldn’t Do That is actually a product of the incredible musical telepathy that the band had evolved by this point, with Ollis’ propulsive drumming to the forefront: “What drove it was my bass drum, which used to go dun-dun-dun-dun-dun-dun-dun-dun pretty much from start to finish! We had a framework and some musical cues, so we knew when to change, but we listened to each other and could go anywhere that anyone wanted to take us. That cowbell at the end that just keeps going – we were meant to finish there, but then we all came back in again and did another bit. The whole thing was very organic. We were all on a space trip together.”

Brock confirms, “We played the whole thing virtually live, though the ‘oohs’ and ‘ahhs’ were put on afterwards. I used to listen to the old New Orleans jazz bands, and their rhythm sections are really driving, playing simple, solid beats that other people could do stuff over, and that’s pretty much the same thing we do now.”

Anderson cites the unexpected influence of Free on the track, his bassline mimicking the octave jumping playing of Andy Fraser, but also adds, “There was something special between me and Terry as the rhythm section. We ended up being like a clockwork motor – once we got into a groove, we were unstoppable.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly for lyric writer Turner, acid played an important role too: “I think I took LSD every day for about two years. We were tripping when we did it, but it’s still saying something: ‘You’re getting nowhere/You’re getting no air/You’re getting aware.’ They merge together, but they’re all meaningful to me. Information, spirituality, raising consciousness, putting people in a trance – it was spontaneously calculated!”

You Know You’re Only Dreaming follows, and starts with a minute or so of cosmic troubadouring from Brock, accompanied by the keening sound of electronic seagulls courtesy of DikMik. “He used to try and play the audio generators in tune, which is quite difficult!” says Brock. Then the song morphs into a moody jam recorded at another point during the sessions. (You can hear the splice at 1:16.)

The most renowned track on In Search Of Space – and Hawkwind’s first explicitly science fiction lyric – is the menacing, magisterial Master Of The Universe. While its popularity might be based on its “relentless riff” in Brock’s assessment, this version is almost cinematic compared to the aural blitzkrieg of later outings, a mysterious stranger riding into town rather than an all-laser-guns-blazing galactic overlord.

For Turner, it felt like a major step forward: “I wasn’t singing until I wrote Master Of The Universe. I wrote these lyrics and said, ‘Right, who’s going to sing them?’ They said, ‘Well, you are!’ So that was my first foray into vocalising. It was an emotional thing for me, you know, ‘I am the centre of the universe… Has the world gone mad or ism it me?’ It’s a sort of self-assessment, an observation of myself.”

A track that’s gained in stature as a portent of things to come, We Took The Wrong Step Years Ago, is an old Brock busking number transformed into a definitive pro-ecology anthem, and a more traditionally melodic song amid the freak-out music that surrounds it. “Dave is a bloody good busker, and that song is an absolute work of art as far as I’m concerned – it’s beautiful,” says Anderson.

Adjust Me is another in-studio improvisation fashioned into a song, and the first time that the recurring theme of android replicas appears in a Hawkwind track. The involvement of Calvert, Moorcock et al pushed the band in a more future-facing direction, though as Brock notes, “All of us used to read sci-fi books constantly.” Its mournful, lost-in-space introduction would be recycled on later recordings such as Seven By Seven and Welcome To The Future, while the main section sounds like it’s harking back to the Eight Miles High-inspired Sunshine Special jam.

The final track, Children Of The Sun, was a last-minute addition to the running order, when it was discovered that the album was five minutes short. Anderson was called at one o’clock in the morning by Chkiantz, who pleaded with the bassist to return to the studio – something that Anderson was disinclined to do, having already handed in his notice to leave Hawkwind due to what he perceived as a violent undercurrent within the band: “DikMik used to try and stab me, but I ended up having to take him to hospital one day. He had a flicknife, but hadn’t put the lock on properly, so when I ducked out of the way, he stabbed the wall and the knife closed on his fingers.”

Given the nature of his departure, it’s ironic that the track Anderson and Turner quickly knocked together is a rose-tinted eulogy to flower children basking in the glory of a new day.

Upon its release, In Search Of Space reached No.44 in November 1971, before returning to the UK charts the following year due to the huge success of Silver Machine, eventually peaking at No.18. Altogether, it spent 19 weeks on the chart, making it by some distance Hawkwind’s best-selling album.

Reaction from the media at home was cautiously positive, with Richard Williams at Melody Maker observing, “In the rush to applaud the Amon Düüls and the Cans from across the water, we’ve all tended to forget the prophets in our own backyard.” But it was the US press that really went to town in praising the album, with Lester Bangs describing it in Rolling Stone as “music for the astral apocalypse.”

Looking back on it now, Anderson says, “I’m proud to have been on it and that it’s stood the test of time.” Ollis says, “I think it’s really good, but I’m surprised that 50 years later there’s still interest in it,” while Brock bluntly states, “I haven’t listened to it in years!”

Yet its impact and resonance is undeniable: this is where modern space rock begins. As Turner concludes, We tried to consciously do something different, to rail against all that conventional music. People frowned on us, but we said, ‘We do it this way.’”

This article originally appeared in issue 124 of Prog Magazine.

In Search Of Xin: What or who is Xin? Prog unearths a mystery behind the album title.

One of the abiding mysteries about Hawkwind’s second album is what exactly it’s called. While commonly referred to as In Search Of Space, Barney Bubbles’ cover design clearly says Xin Search Of Space. And as it was Bubbles who gave the album its title, maybe the latter is correct? Terry Ollis confirms: “Barney said to me, it’s pronounced ‘Zin’. But what that means, I don’t know!” However, obviously not everybody got the design memo, because the original album’s spine, inside cover and record label all say plain In Search Of Space. Still, whatever you call it, it’s definitely not X In Search Of Space.