On Saturday August 22, 1987, 75,000 metalheads undertook a pilgrimage to Donington Park for the eighth staging of the annual Monsters Of Rock festival. The day was notable for several reasons. The bill – Bon Jovi, Dio, Metallica, Anthrax, WASP and Cinderella – was the only all-American lineup in the event’s history. The organisers misspelled the festival site as ‘Donnington’ on the stage banners. And Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson gave a none-too-subtle clue as to the identity of the following year’s headline attraction when, at the climax of his guest spot with Bon Jovi, he told the rain-sodden crowd, “See you next year.”

Amid the denim, leather and spandex-clad hordes gathered in the East Midlands that weekend, one man’s sartorial taste drew much comment. In choosing to wear a Public Enemy T-shirt onstage, Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian could hardly have stood out more had he appeared before the Donington faithful in a tutu.

While Slayer guitarist Kerry King’s cameo on the Beastie Boys’ No Sleep Till Brooklyn and Aerosmith’s collaboration with Run-DMC on Walk This Way had done much to break down barriers between the worlds of hip hop and metal, Ian’s public endorsement of the Long Island rap crew was controversial. Unlike the cartoon threat of the bratty Beasties and their Adidas-wearing brethren from Hollis, Queens, Public Enemy were viewed as radical, subversive and genuinely revolutionary.

Many media commentators looked at the band’s logo – a silhouette of a black man framed in a sniper’s crosshairs – their (fake) Uzi-wielding S1W posse and their uncompromising, militant lyrics preaching resistance and rebellion and wrongly concluded that Chuck D’s prophets of rage had arrived to soundtrack a race war. What was a nice Jewish boy like Scott Rosenfeld doing pledging allegiance to such a group?

In truth, even as metal fans in the UK were largely preoccupied with their own Thrashers vs Poseurs civil war, hip hop was already winning hearts and minds in the continent to the left. Public Enemy and their West Coast compatriots NWA and Ice-T weren’t singing about avenging Satanic goblins or the impending threat of nuclear Armageddon. Instead, their songs laid bare the harsh realities of life on the streets of inner-city Amerikkka in graphic, unflinching detail. That middle-class suburban white kids from Long Beach to Long Island would never experience racial profiling, police brutality or drive-by shootings was largely irrelevant: hip hop sounded explosive, looked dangerous and felt real.

The new generation of hip hop artists were given a visual identity by LA photographer Glenn E. Friedman. Having begun his career photographing ‘Dogtown’ skateboarders and the first wave of Southern Californian hardcore bands, Friedman was instinctively drawn towards rebels with a cause (his first hardcover photo book was titled Fuck You Heroes), and in hip hop’s new breed he saw the same fearlessness, focused energy and punk-rock attitude that inspired the skater and hardcore communities. His iconic portraits of Def Jam’s emerging artists were bold, stark and ‘heavy’ in ways that totally eclipsed the posturing machismo of the metal acts of the day. Soon enough, their distinctive stylings – Adidas tracksuits, baseball caps and basketball sneakers – were de rigueur for angst-ridden adolescents seeking to make rebellious statements of their own.

- Nightwish star in the new Metal Hammer – celebrating the women who define metal

- "We were a f**king livewire": 25 years of Rage Against The Machine

- Every Limp Bizkit Album Ranked From Worst To Best

- A Metalhead's Guide To... Hip Hop

Even as Friedman’s photographs delineated the common ground between skate, punk rock and hip hop culture, a new band emerged to make the synthesis complete. Rage Against The Machine combined the adrenalised rush of skating, the kinetic ferocity of punk rock, the brooding menace of hip hop and the brutish power of 70s hard rock in one inflammatory package. Articulate, intense and confrontational, the multi-racial LA collective’s thrillingly apoplectic guerrilla manifestos owed as much to Public Enemy as The Clash, Bad Brains and Led Zeppelin, and frontman Zack de la Rocha’s oversized, baggy streetwear enabled him to imbue their incendiary performances with a thrilling physicality as fluent as his furious, flowing rhymes. Here, truly, was the sound of liberation and a blueprint for the future.

No sooner had Rage’s self-titled debut album hit the streets than their record label begin corralling hard rock and hip hop artists together to record collaborations for the soundtrack to the 1993 action thriller Judgment Night. Reviewing the resulting 11-track album, Rolling Stone magazine commented: “Judgment Night’s bracing rap rock is like the wedding of hillbilly and ‘race’ music that started the whole thing in the first place… It’s an aspiring re-birth.”

RATM guitarist Tom Morello noted: “I’m quite confident that at the same time, record company executives in boardrooms across the nation were saying, ‘If only we can find a Rage Against The Machine that would make five videos per record and have songs about chicks and show off.’”

They wouldn’t have long to wait.

“When Rage Against The Machine came out in 1992, that was fucking huge for me,” admitted Limp Bizkit frontman Fred Durst. “I came from this breakdance and hip hop background so to see this band put a lot of hip hop into this heavy rock was really inspiring.”

“Everyone in our circle was listening to a lot of West Coast hip hop, and a lot of that stuff was real minor key and dark anyway,” Korn bassist Fieldy added. “If you could take that to the next level, you could make it heavy metal.”

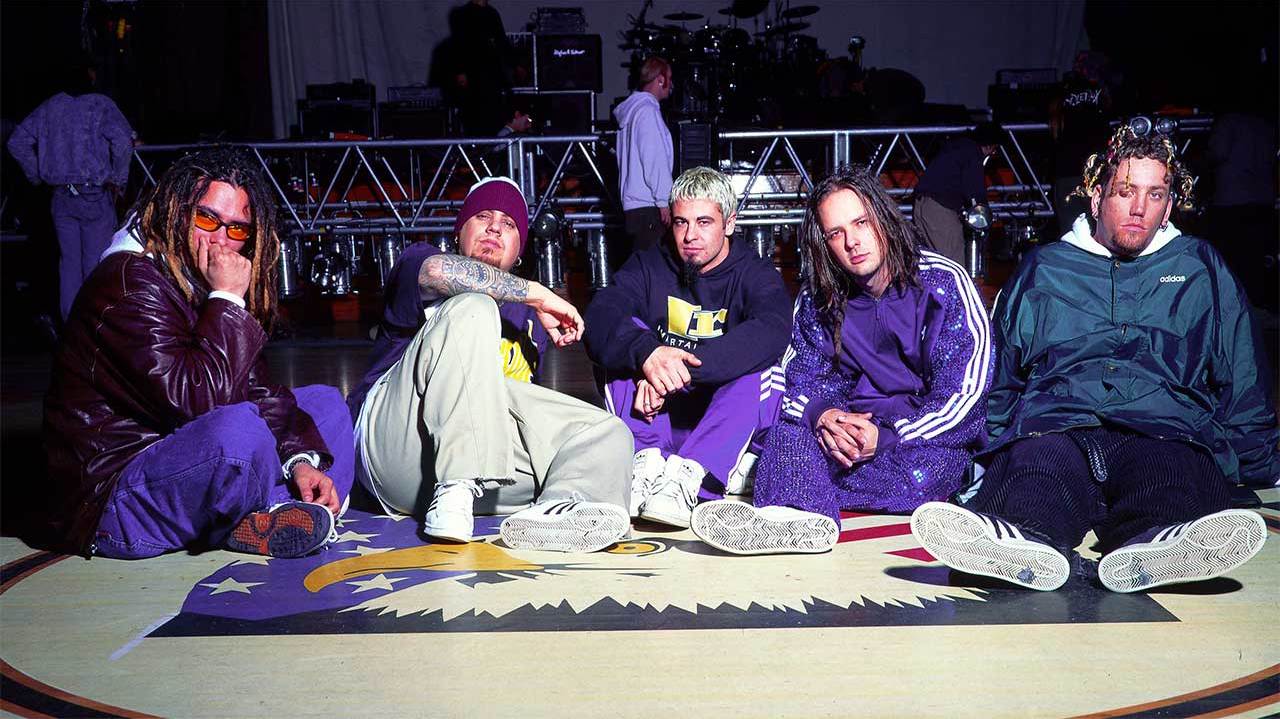

It would have been ludicrous for a bunch of white suburban metalheads to take on the gangsta posturing of 90s hip hop, but just as rap DJs developed a keen eye for pilfering musical sources from across a broad spectrum of a century of recorded music, so a new generation of hip hop-loving rockers sampled fragments of rap culture with unselfconscious glee, putting new twists on already iconic symbols, as with Jonathan Davis’s decision to bling out his Adidas tracksuits with fake fur and metallic sequins, and even traditional metal bands like Machine Head and Fear Factory donning sports clobber.

It set the tone for the rest of the 90s and into the 2000s, where for the better part of a decade, denim and leather were left dead in the dirt and heavy metal clichés seemed to be gone forever. Korn and Limp Bizkit not only borrowed hip hop’s aesthetics and sonic template, but cannily appropriated its savvy cross-brand marketing strategies too, inviting the likes of Eminem, Dr. Dre, Method Man and Ice Cube to make cameo appearances both on record and in promotional videos.

At a time when the kings of metal, Metallica, were rebelling against their own success, fucking with their alpha male image by embracing metrosexuality, high art and ‘alternative’ culture on Load and Reload, metal’s nu breed were drawing upon the energy, soul and colour of urban street life to bring the noise in increasingly flashy and provocative ways. Suddenly, the old school looked like old hat, and nu metal promised the true sound and style of youth music with attitude.

A decade on from Public Enemy infiltrating metal’s hallowed turf at Donington, a new generation had the genre’s old gods in their crosshairs.