Nineteen sixty-nine was one helluva year for Led Zeppelin. In the short span of 12 months they played close to 150 shows, recorded two best-selling albums, toured the US five times, and established themselves as one rock’s top box-office draws. In the harsh winter of ’68 they had been lucky to get $1,500 (around £883) for a club gig, but by the time 1970 rolled around, they were demanding as much as six figures a show.

The band’s meteoric rise had been breathless. While the music press weren’t particularly kind to them, their dramatic, sexually explicit hard rock was almost irresistible to a new generation of kids searching for something new and exciting that wasn’t “the same old Beatles and Stones”. But after a year of non-stop touring, recording and shagging, the band were ready to take a break.

It was singer Robert Plant’s idea to head for the hills – the Cambrian Mountains in Wales, to be exact. The 22-year-old remembered an 18th-century cottage called Bron-Yr-Aur he had visited in his youth, and felt it would be great place to temporarily escape life in the fast lane and commune with nature. Plant extended an invitation to his co-writer, guitarist and producer Jimmy Page, and in the spring, the two men took their women, instruments and supplies to the bucolic retreat to recharge their batteries and “get back to the garden”.

“It was time to take stock, and not get lost in it all,” Plant said later. And what better way to keep it real than at a place with no electricity, candles for light, water from a stream and an outside toilet?

The story of Plant and Page’s regenerative trek to Wales looms large in Zeppelin folklore, with many assuming that most of the acoustic-based songs that eventually appeared on Led Zeppelin III were written there. Page disputes that notion, but doesn’t dismiss the significance of the journey.

“When Robert and I went to Bron-Yr-Aur we weren’t thinking: ‘Let’s go to Wales and write,’” says Page. “The original plan was to just go there, hang out and appreciate the countryside. The only song we really finished while we were there was That’s The Way, but being in the country established a standard of travelling for inspiration and set a tone for Led Zeppelin III.”

While it might not have been conceived as a writing trip, the singer and guitarist’s stay in the Welsh mountains was deemed important and influential enough to be acknowledged on the album’s sleeve, stating: ‘Credit must be given to Bron Y Aur a small derelict cottage in South Snowdonia for painting a somewhat forgotten picture of true completeness which acted as an incentive to some of these music statements.’

Little did the band know that this ‘incentive’ and subsequent ‘tone’ would end up sending massive shockwaves throughout the rock world. Led Zeppelin’s pastoral third album was recorded at Olympic Studios in London and released in October 1970. It seemed almost self-destructively perverse – a 360-degree retreat from the testosterone-infused hard rock that had made them international superstars.

John Bonham teased the press about the band’s intended direction when Zeppelin regrouped for the first studio sessions of III in late May. ‘’We’ll be recording for the next two weeks and we are doing a lot of acoustic stuff as well as the heavier side,” he told the Melody Maker. “There will be better quality songs than on the first two albums.’’

The drummer wasn’t wrong. Six of the 10 tracks on the third album were built around the sweet ’n’ bitter strains of Page’s acoustic Harmony guitar as the band touched on everything from traditional bluegrass (Gallows Pole) to country blues (Hats Off To (Roy) Harper), to a folk song so upbeat you could square-dance to it (Bron-Y-Aur Stomp). To emphasise the rustic nature of the album, Zeppelin even changed their appearance, growing facial hair to Hobbit-like proportions and wearing clothes that made them look more like hippie farmers than sex gods. Fans and critics were dazed and confused, but the band stood their ground.

“We were so far ahead that it was difficult for people to know what the hell we were doing,” Page told journalist Brad Tolinski in the 2012 book Light & Shade: Conversations With Jimmy Page. “Critics especially couldn’t relate to it. Led Zeppelin was growing. Where many of our contemporaries were narrowing their perspective, we were really being expansive. I was maturing as a composer and player, and there were many kinds of music that I found stimulating, and with this wonderful group I had the chance to be really adventurous.”

Soon after the album’s release, Page was keen to emphasise Zeppelin’s evolution. “There is another side to us’’ he said. “Everyone in the band is going through changes. There are changes in the playing and the lyrics. Robert is really getting involved in his lyric writing. This album was to get across more versatility and use combinations of instruments. I haven’t read any reviews yet, but people have got to give the LP a reasonable hearing.’’

Page would go on to read the reviews. Some writers went so far as to accuse the band of jumping on the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young acoustic-rock bandwagon, which Page called “pathetic”, noting that acoustic guitars were all over the first two albums and arguing that they were at the core of everything the band did. The reviews so incensed the guitarist that he refused to grant any press interviews for the next 18 months after the album’s release.

Plant, at the time Led Zeppelin III came out, was more direct: “You can just see the headlines, can’t you? ‘Led Zeppelin go soft on their fans’ or some crap like that. But now that we’ve done [this album] the sky’s the limit. It shows we can change. It means there are endless possibilities for us to go in. We won’t go stale, and this proves it.”

The truth is, the third album should have come as no surprise to anyone paying full attention to the band. The radical seeds that sprouted onIII had been planted years earlier. Throughout the 60s, as Page toiled as London’s top session guitarist, very little escaped his attention. Like a musical sponge, he absorbed every lick the Chicago blues boom had to offer, took copious notes on contemporary folk-guitar virtuosos like John Fahey and Bert Jansch, and even purchased a sitar years before world music caught the attention of Beatle George Harrison.

He had already started applying those exotic flavours to rock’n’roll during his brief stint with The Yardbirds, and developed those ideas further on such early Zeppelin tracks as Black Mountain Side, which featured an Indian tabla musician, and Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You, which improbably married a Joan Baez song to heavy metal power chords and a flamenco guitar solo. The acoustic songs, Page opined, were designed to create dynamics both on the albums and in live performances, and that the harder songs “wouldn’t have as much impact without the softer ones”.

Yes, some thought Led Zeppelin III was commercial suicide, but in retrospect it was a brilliant gambit. Not only did the album prevent the quartet from becoming hard-rock caricatures like, say, Deep Purple or Ten Years After, but it also gave them an opportunity to take an important evolutionary leap forward. Often marginalised as ‘the acoustic album’, III was much more than that: it represented a truly daring leap in synthesising the folk, rock and world music elements found on the band’s first two albums into what one thinks of as ‘the Led Zeppelin style’.

The tense and mysterious Friends, for example, was the result of an experimental tuning Page designed specifically to capture the droning vibe heard in North African music. With its Eastern tonalities and ominous string arrangement reminiscent of English composer Gustav Holst’s Mars, Friends was undeniably a gateway to future masterworks like Kashmir and Four Sticks. And it makes you wonder if Stairway To Heaven or Over The Hills And Far Away would have existed without stylistic forerunners like That’s The Way or Gallows Pole.

Page was spreading his wings, and the Zeppelin III sessions also gave Robert Plant the opportunity to grow as a songwriter. No longer forced to simply beat his chest and crow about the size of his knob, he wrote his first truly great lyric, for That’s The Way. Amid Page’s cascading acoustic guitars, dulcimer and weeping pedal steel, Plant weaves a mournful southern Gothic tale on a par with Bobbie Gentry’s 1967 hit Ode To Billie Joe. With its haunting ambiguity, the song could be about class, racism, homosexuality or even ecological disaster. It’s sophisticated, secretive and flat-out beautiful. And, Lord knows, it’s a far cry from ‘I’m gonna give you every inch of my love’.

Plant has said the third album was “incredibly important for my dignity”. Perhaps the same could be said for the entire band.

Led Zeppelin were daring, but not crazy enough to completely abandon hard rock. While the album has its share of quiet moments, it also has plenty of loud ones – peculiar as they may be.

Immigrant Song is one of the heaviest and most exciting tracks in the band’s entire catalogue. On the surface it seems pretty straightforward, until you realise it’s a song about Vikings, the main vocal riff sounds like Bali Ha’i from the Broadway musical South Pacific, and that the rhythm guitar borrows from Link Wray’s rockabilly classic Rumble.

Its lyrical inspiration came when Zeppelin took some time out from the studio and ventured to Iceland to play a show in on June 22 as part of a cultural exchange arranged by the British Government. Their first gig in the best part of three months, it took place at Reykjavik’s Laugardalsholl Sports. More importantly, just as the Welsh mountains had proved inspiring earlier in the year, Plant let his imagination run riot as he contemplated Iceland’s endless day.

“It was one of those times when you go to bed at night but you don’t sleep because the daylight’s still there – a 24-hour day,” the singer said. “There was just an amazing hue in the sky, and it was one of those things that made you think of Vikings and big ships – and John Bonham’s stomach.”

Less than a week later the band returned to the UK to headline the Bath Festival Of Blues & Progressive Music. The new song had already made such an impact on Zeppelin that they chose to open the show with it, and the British public heard Immigrant Song for the first time.

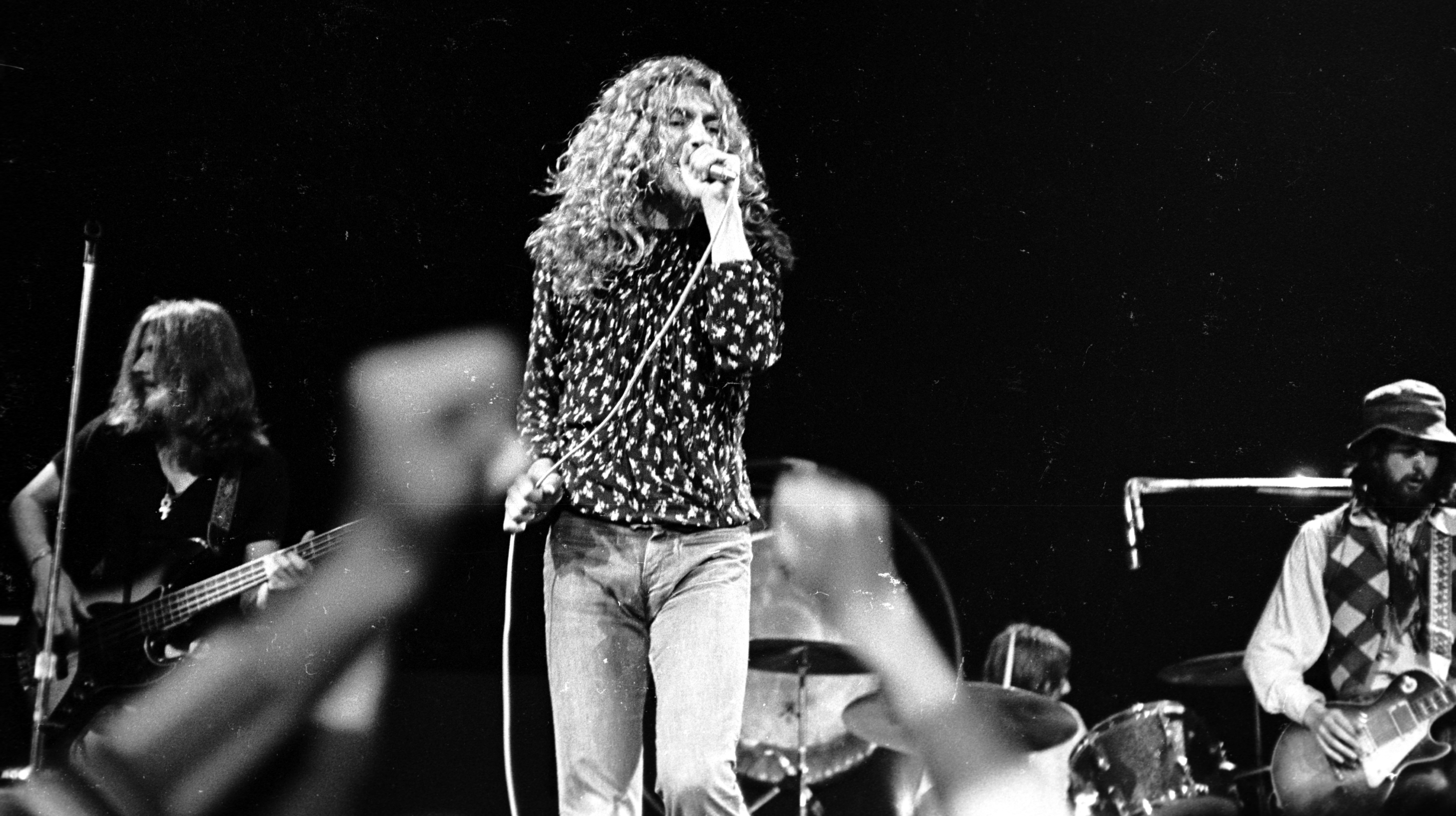

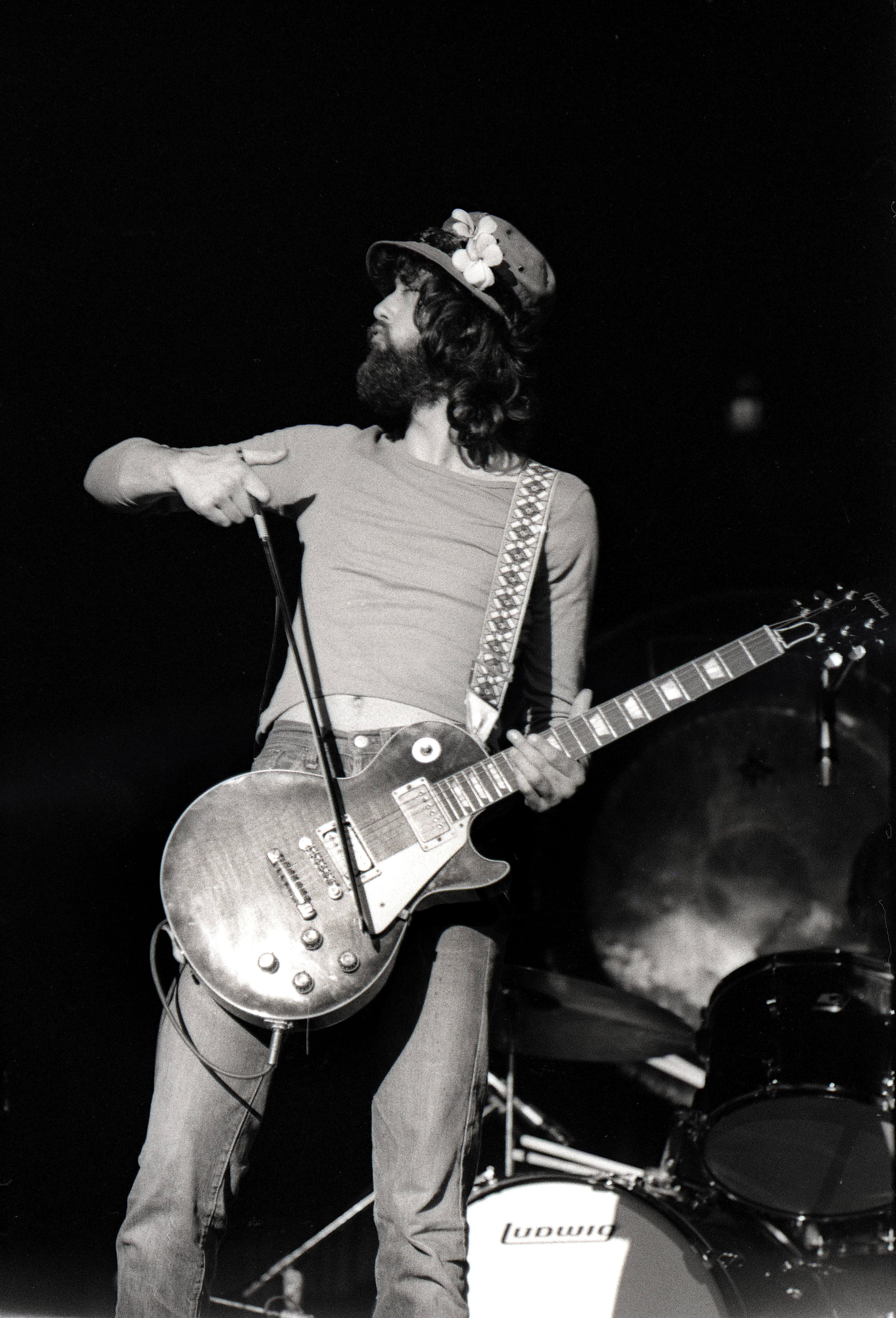

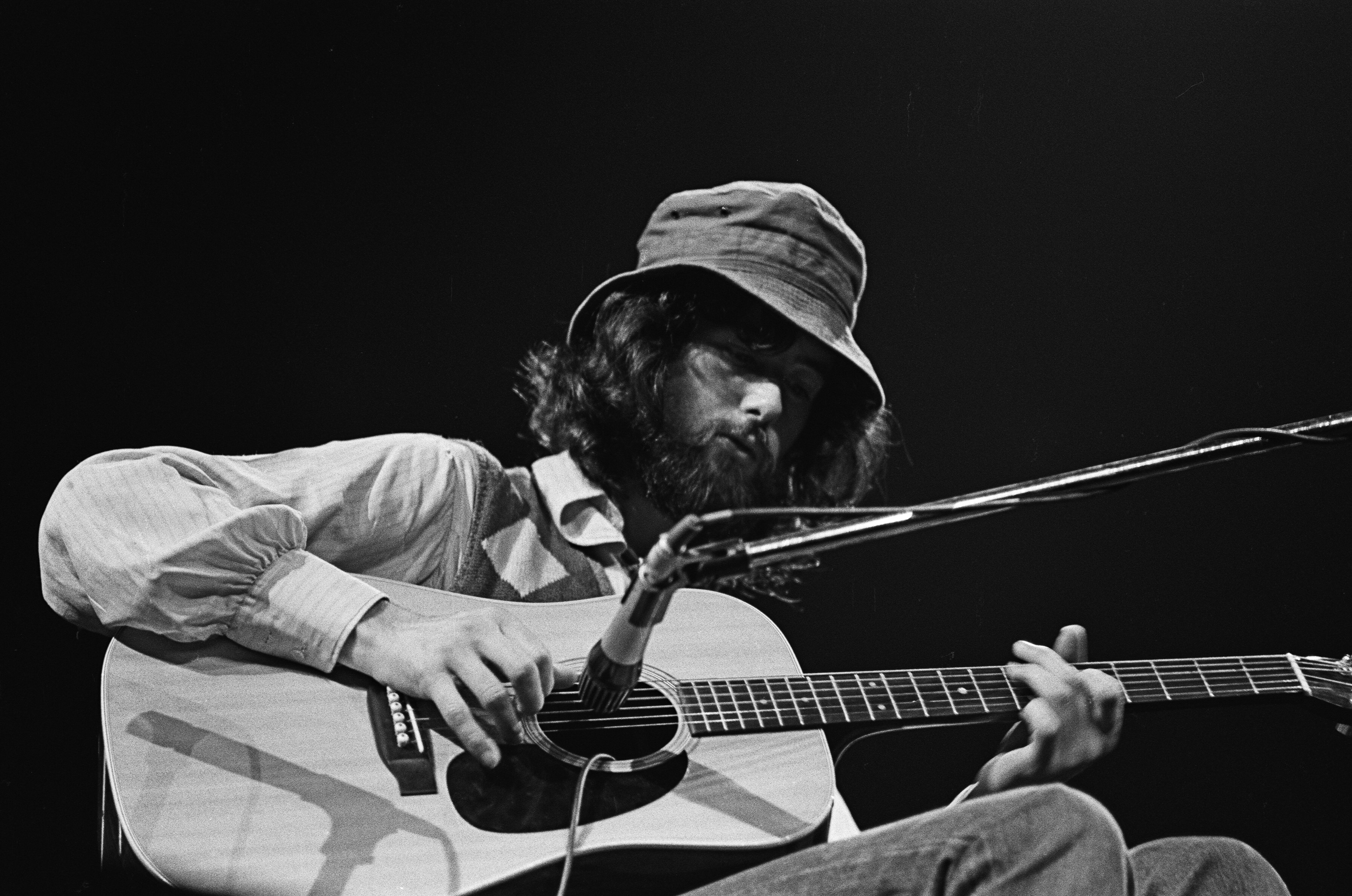

Unsurprisingly, their Bath show was a sensation, prompting Melody Maker to enthuse: ‘Led Zeppelin stormed to huge success at the Bath Festival. About 150,000 fans rose to give them an ovation. They played for over three hours – blues, rock’n’roll and pure Zeppelin. Jimmy Page, in a yokel hat to suit the Somerset scene, screamed into attack on guitar, John Paul Jones came into his own on organ as well as bass, and John Bonham exploded his drums in a sensational solo. And the crowd went wild demanding encore after encore… a total of five!’

“Bath was a turning point in recognition for us,” Page said. “There have been one or two magical gigs and Bath was one of them.”

“Bath was great,” remembered manager Peter Grant later. “I went down to the site unbeknown to [promoter] Freddie Bannister, and I found out from the Met Office what time the sun was setting, and it was right behind the stage. And by going on at eight in the evening I was able to bring the lights up a bit at a time. And it was vital we went on to match that.”

Even more crucially than any show-stopping sunset appearance, the Bath gig would herald a new era in Zeppelin’s evolution. Midway through their set, Jimmy Page swapped his Gibson Les Paul for a Martin acoustic guitar, and John Paul Jones picked up a mandolin. As Page played a few opening chords, Plant stepped to the mic. “This is called The Boy Next Door, for want of a better title [a better title would emerge – That’s The Way, when it finally appeared on Led Zeppelin III]” he said. It was the first time Led Zeppelin played acoustically in the UK.

It isn’t all folky acoustic bluster on Led Zeppelin III; there’s Since I’ve Been Loving You, a standard three-chord, 12-bar minor blues that actually has way more than three chords and who knows how many bars, because the damn thing never seems to repeat. Or what about Celebration Day, a song that sounds like a berserk Slinky due to the fact that John Paul Jones is playing his bass with a guitar slide?

Like I said, loud but peculiar.

Then, of course, there was the matter of the Aleister Crowley quote etched into the run-off groove of early pressings of the album. Yes, the Beatles had put his image among many others on the cover of 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, but this seemed a little more covert; a little more dangerous, adding another disturbing layer to the already dark mythology of Led Zeppelin.

The phrase ‘Do what thou wilt’ and ‘So mote it be’ were inscribed on the vinyl by recording engineer Terry Manning during the final mastering process: ‘Do what thou wilt’ on side one, and ‘So mote it be’ on side two. The phrases were homage to Crowley, a practitioner of black magic who was once called “the most evil man in England”, and whom Page was quite enamoured with.

This phrase is from one of the fundamental principles of Aleister Crowley’s philosophy of Thelema: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law. Love is the law, love under will. There is no law beyond do what thou wilt.”

By the time of the release of the album, it was still rather an open secret that Page was interested in the dark arts, and the inscriptions on the album were one of the first public signifiers. It wouldn’t be until the next year that the guitarist would buy Crowley’s Loch Ness estate Boleskine House. This was something Page would downplay later, explaining to Rolling Stone in 1976: “I do not worship the devil. But magic does intrigue me. Magic of all kinds. I bought Crowley’s house to go up and write in. The thing is, I just never get up that way. Friends live there now.”

Whenever he’s queried today, Page silences any conversation on the subject by advising the hapless interrogator: “Forget the myths. Because it was really all about the music.”

Which mostly it was, and moving forward into the future. This was a band who were staunchly opposed to repeating what they’d done before. “There was no way the third album was going to be like the first. If there was a Zeppelin philosophy, it was always: ‘Ever onwards. Let’s see what we can do next,’” Page said in 2005.

“With Since I’ve Been Loving You, we were setting the scene of something that was yet to come,” says Page. “It was meant to push the envelope. We were playing in the spirit of the blues, but trying to take it into new dimensions dictated by the mass consciousness of the four players involved.

“The same thing goes for the folk stuff as well. It’s sort of, ‘Well, this is how it was done in the past, but it now has to move.’ There was no point in looking back. We were just inspired with this energy that we had collectively.”

“On Hats Off To (Roy) Harper, Robert and I were just singing and playing in the tradition of Sonny Terry And Brownie McGhee. Then we put the vocal and harmonica through an amp and turned on the tremolo, and suddenly it sounded edgy and surreal. It was a perfect way to end the album. We were tipping our hat to the country blues, but presented it in a way that no one else had done.”

Perhaps the most surreal thing about Led Zeppelin III is that, after all these years, its time may have finally come. While it will never be their biggest album, it might be their most contemporary. Think about it: ‘dudes with beards, wearing expensive thrift-shop clothing, playing edgy folk music that borrows liberally from world music and heavy metal’ sounds very modern indie rock to these ears. It’s no wonder that the album has sold three times as many copies in the last two decades as it did in the first twenty years since its existence.

Perhaps this is what Page – ever the mystic – was talking about when he said: “We knew what we were doing was right and that it was actually breaking new ground. We were cutting with a machete knife through the jungle, and discovered a temple of the ages.”

Trailblazing can be tough business, but very satisfying when smart people follow your footsteps. Four decades later, it seems that the temple Led Zeppelin III built has become a very busy place indeed. Artists such as Laura Marling, Fleet Foxes, Devendra Banhart and even Mumford & Sons, whose thumping beats have at least one muddy boot in Bron-Y-Aur Stomp, have been known to drop in for a visit.

If one was really going to quibble with the concept of Led Zeppelin III, it might be with the notion that the band were doing anything particularly shocking or original. While it’s agreed that comparing them to Crosby, Stills & Nash was patently absurd, bands like Fairport Convention and The Byrds were all attempting to modernise folk music to some degree in the 60s and 70s. In a 2010 interview, Page flicked away that idea, but made a valid point, saying that while he admired those bands and what they were doing, he didn’t think anyone would ever confuse Led Zeppelin with Fairport or the Incredible String Band.

“They were coming from a much more traditional place, and I was coming from so many different areas. But maybe,” he adds with a laugh, “I was just coming from a rock’n’roll head. Something like Friends really isn’t – it isn’t traditional music, but I liked that we could go in that direction and put our own spin on it. At the same time, I don’t ever think we lost sight of the fact that we were a rock band.”

As for the bad reviews, Page has softened over the years, saying that in hindsight he could see how III was misunderstood. “Journalists were in a rush and they were looking for the new Whole Lotta Love and not actually listening to what was there,” he told writer Nigel Williamson. “It was too fresh for them and they didn’t get the plot. It doesn’t surprise me that the diversity and breadth of what we were doing was overlooked or under-appreciated at the time.”

In the final analysis, after the album was released in October and the dust settled, Zeppelin simply went on their way as they always had, and immediately began writing and working on what would eventually become their biggest album ever: Led Zeppelin IV. With the same acoustic guitar that he used on the maligned III, Page composed some of the band’s most beloved anthems, including Stairway To Heaven, The Battle Of Evermore, Going To California and Four Sticks. Critics – and everyone else – be damned.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #198.