Early June, 1979. At a pub named The Swan, close to the famous Hammersmith Odeon, Iron Maiden, a young heavy metal band from the East End of London, were due on stage. But there was a problem. Their singer had just been led away in handcuffs to the local police station.

Paul Di’Anno had been arrested for possession of an offensive weapon – a flick-knife found by police when they frisked the singer during a random stop-and-search outside the pub. Di’Anno, a classic Cockney wide boy, was good at talking himself out of trouble. But on this occasion he was out of luck.

At The Swan, the band’s bassist Steve Harris nervously broke the news to the man who had booked the gig. Rod Smallwood – at 29, six years older than Harris – had been looking for a way out of the music business following spells as an artist manager and booking agent, but having heard an Iron Maiden demo tape, passed on to him by a friend who worked with Harris, Smallwood had sensed potential.

He’d booked two gigs for the band. The first – at The Windsor Castle on Harrow Road – ended in farce when the band, not realising the prospective manager was there, refused to play to a near-empty pub until 30 or so fans and friends travelling from the East End arrived, leading to an argument with the landlord who told them he would get them barred from North London. The second gig was at The Swan.

When Smallwood heard that Di’Anno had been nicked, he turned to Harris and told him, “You’ve got to play – your fans are here on time for you.”

Harris hesitated, but Smallwood pressed him. “Do you know the words?”

“Yeah,” Harris replied, “I wrote ’em.”

“Can you sing?”

“Not really.”

“Can you try?”

“Yeah, sure.”

Ten minutes later, Iron Maiden got up on The Swan’s tiny stage. They played as a trio: Harris, guitarist Dave Murray and drummer Doug Sampson. At this point in the band’s career, they still hadn’t settled on a permanent second guitar player to partner Murray, but even with only one guitarist and with Harris singing, Maiden’s performance got a great reaction from the pub crowd.

As Harris recalls, “When you’re up against it, you just have to go for it. There were some things I couldn’t physically play and sing at the same time. But it fired me up. Things like that bring out the best in you.”

For Rod Smallwood, this was the moment when he first believed that Iron Maiden could go all the way to the top.

“Steve couldn’t sing,” Smallwood laughs now, “but I’d never seen anybody like him on stage. It was the way he and Davey looked the audience in the eye. I loved the attitude. It sounds silly or easy to say looking back, but after that one gig I knew they’d be fucking huge – plus they were playing songs like Prowler, Iron Maiden, Phantom Of The Opera and Wrathchild!”

Fewer than 50 people saw Iron Maiden at The Swan, but it was the most significant gig the band has ever played. Most importantly, it bonded Harris, the band’s leader, with Smallwood, the man who would become their manager. This was the beginning of a long and close relationship that would propel Iron Maiden to superstardom. But what was also significant on that night at The Swan was the arrest of Paul Di’Anno.

The band had laughed off the incident when the singer returned to the pub after the show, having been released pending a fine. But here was a portent of trouble to come. When Iron Maiden achieved their greatest success, they would do so with a different singer.

The history of Iron Maiden is a classic three-act drama: rise, fall, and resurrection. And at the centre of that story is the man who replaced Paul Di’Anno in 1981, Bruce Dickinson. It was the single-minded vision of Steve Harris that would make Iron Maiden the greatest metal band of its generation, and it was Rod Smallwood’s belief in that vision – soon to be allied to his partner Andy Taylors’ keen business acumen – that would develop Maiden into a global franchise.

But it was Bruce Dickinson whose powerful voice and energetic showmanship transformed Maiden into a truly world class band; it was Dickinson’s exit in 1993 that precipitated the band’s decline; and it was his return in 1999 that completed their comeback.

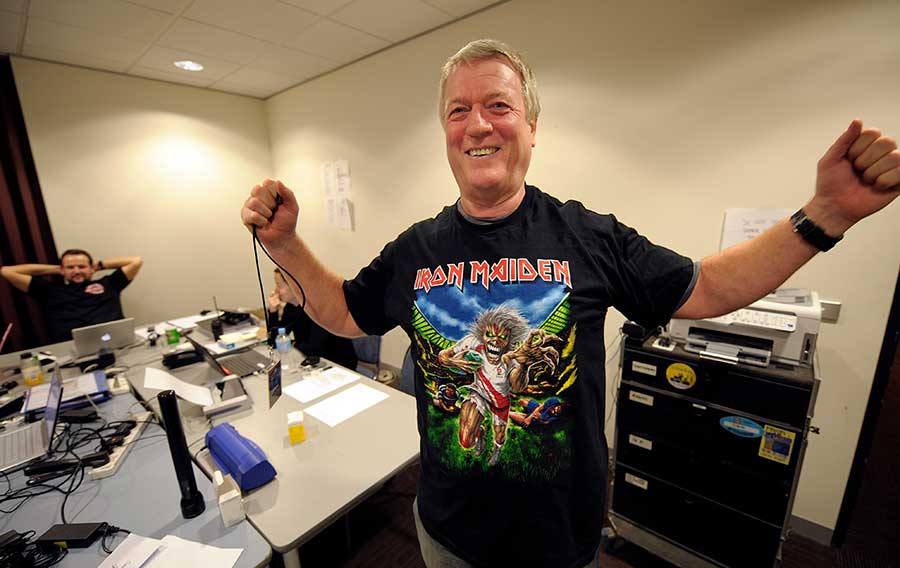

In the 30 years since Bruce Dickinson first joined Iron Maiden, it is these three “control freaks,” as Smallwood calls them, that have defined the band’s history: Harris, the stubborn, no-nonsense, working class Cockney; Smallwood, the brash Yorkshireman; Dickinson, the voluble, opinionated, multi-talented over-achiever.

Iron Maiden always was and always will be Steve Harris’s band, even if Harris himself would never say it explicitly. It was Harris who formed the band on Christmas Day, 1975, and he has led them ever since, writing the bulk of the band’s songs. But in Rod Smallwood, Harris found a manager as influential and hands-on as Led Zeppelin’s Peter Grant. And in Bruce Dickinson he found not just a foil but also an equal, a self-confessed “awkward customer” with his own, strongly expressed, views on what Iron Maiden should and should not be.

There would be conflict within Iron Maiden: most famously, a rivalry between Harris and Dickinson, which has only really been settled since the singer’s return to the group. But what united them is a common goal, a determination to make Iron Maiden the biggest and best heavy metal band in the world.

Beginning with The Number Of The Beast in 1982 – the band’s first album with Dickinson, and their first UK number one – Iron Maiden became the most successful metal act of the 80s. They did it the old-fashioned way, the hard way, via a series of marathon world tours, with minimal media support beyond a few specialist rock magazines and radio shows. And they succeeded without selling out.

Maiden had hit singles, a dozen reaching the UK top 20 in the 80s alone, but their music was never radio-friendly by design. They were signed to major label EMI, but they retained absolute artistic control. And it was this fiercely independent approach to the music business, as much as the music itself, that made Iron Maiden an inspiration to bands such as Metallica, whose drummer Lars Ulrich stated unequivocally: “Maiden was our one true role model.”

As Harris says: “We always stuck at what we believed in. I’m proud of that.”

Steve Harris is an atypical rock star. Unassuming, never flash, he plays down what Rod Smallwood says of the hierarchy in Iron Maiden. “I wouldn’t say I’m a control freak,” Harris says. “I just like to get things done.” But while he dislikes the term that Smallwood applies to the band’s modus operandi, “a non-democratic democracy”, he admits: “I know what Rod means. A lot of the time, we’ve done stuff mainly between me and him.” And discussing his role as Iron Maiden’s leader, his logic is simple: “I think with any band, you need one person to really take the bull by the horns. Most people don’t want to do the grunt work, but I took it upon myself to do it all right from the start.”

In the early days, Harris managed Iron Maiden and booked their gigs. He poached Dave Murray and Paul Di’Anno from rival bands. He wrote or co-wrote all of the band’s early material, and utilised his skill as an architectural draughtsman to design the band’s logo. What Rod Smallwood offered Harris and Iron Maiden was greater music industry experience, key contacts, and perhaps most important of all, fierce commitment. As Smallwood says: “Steve found someone whose work-rate and belief was equal to his own.”

Smallwood had big dreams. “I always wanted to be a manager,” he says. “I envisaged a band like Zeppelin, playing in great big fields all over the world.”

And in Steve Harris, he saw his Jimmy Page, a born leader with genuine talent and absolute conviction.

“With a band, not everyone wants to lead,” Smallwood explains. “But Steve was unquestionably the leader of the band and everybody else was happy with that. Before I came along it was all Steve, it was all his determination and energy and integrity. But Steve is 100 per cent music. He doesn’t want to deal with a record company. When I came in, it was my job to put a barbed wire fence around him to let him do what he wanted.”

Such was the bond between them that Smallwood was only officially contracted as Iron Maiden manager after he had brokered the band’s record deal with EMI on November 12, 1979. There was no clamour to sign Iron Maiden: CBS passed on the band, believing the songs were not strong enough. Nevertheless, Smallwood was able to secure a lengthy contract with EMI that proved hugely beneficial to a young band that needed time to build a career.

“It was crucial,” he says, “that we insisted on a three-album deal. But EMI would only give us £50,000 for three albums, plus recording costs. And we needed to buy equipment. We needed to tour. So I took a £35,000 advance on the first album, £15,000 on the second, and nothing on the third. The aim was always to renegotiate that deal after three albums.”

Smallwood had briefly co-managed another EMI act, Steve Harley And Cockney Rebel, for a couple of years and an art-rock band named Gloria Mundi that was signed to RCA. But his business partner Andy Taylor, a friend from Cambridge University, was a shrewd accountant, and Smallwood had a keen sense of strategy. From the outset, he had a global vision and long game plan for Maiden. “Metal is a worldwide phenomenon,” he says. “So we actually looked at developing the whole planet in parallel.”

Smallwood also understood that in the short term, both he and the band would have to live “hand to mouth”, a tradeoff worth making for a three-album deal.

“No-one took anything out. We were all on what we needed to live, nothing more.” When the band recorded The Number Of The Beast the members were still only on wages of £60 a week.

Says Harris: “Me and Rod really subsidised a lot of things. I wrote all the songs, pretty much, and I didn’t take a penny from it. And Rod didn’t take any commission. That shows commitment. It’s like any business – we had no guarantee that we were going to get any sort of money out of it. But it was never about the money. We just wanted to be a big band.”

To this end, Harris would have to be ruthless. Before the first Iron Maiden album was recorded, the band acquired a new guitarist, Dennis Stratton, and a new drummer, Clive Burr, replacing the less accomplished Doug Sampson. For Harris, firing Sampson was necessary but difficult.

“I had some sleepless nights over it,” he admits. “And for a while I was called Sgt. Major Harris, or the Ayatollah. But I did what I had to do.”

The album – titled simply Iron Maiden, and recorded for just £12,000 – was a critical and commercial success. Harris would never be happy with the album’s production, by Will Malone, but the raw sound was perfectly suited to the band’s aggressive style, with Di’Anno’s snarling voice giving Maiden a tough, streetwise edge.

Released on April 14, 1980, the Iron Maiden album reached number four on the UK chart and went on to sell 350,000 copies worldwide.

“Those were significant sales for a debut album,” says Smallwood. And this strengthened Maiden’s hand with EMI. “If you’re showing success internationally from the word go, they know not to interfere.”

Moreover, the image on the cover of Maiden’s first album gave the band a strong visual identity, effectively a trademark, which would be exploited throughout their career. The monstrous figure on that cover, painted by artist Derek Riggs and named Eddie after the crude skull stage prop that had been used in the band’s early shows, became Iron Maiden’s figurehead.

“The band didn’t have a Mick Jagger,” Smallwood says. “We needed a symbol, and that was Eddie.”

The power of Eddie as a marketing tool – plus Harris’ readily identifiable logo –established Maiden’s merchandising as a key revenue stream. And nobody appreciated this more than Kiss, the band whose theatrical image and marketing savvy made rock merchandising into an industry in the 1970s.

When Maiden supported Kiss on a European tour in August 1980, Kiss bassist Gene Simmons told Smallwood he loved Eddie and predicted: “Iron Maiden is going to take over from Kiss as the biggest merchandising band in America.”

“Maiden immediately struck me as a band with huge potential,” says Simmons today. “The band was both musical and powerful: a rare combination. And being the Capitalist Pig that I am, Eddie struck me as an iconic visual that would buy everyone in the band big houses.”

Smallwood adds: “We had strong merchandising from the word go. If we hadn’t, we couldn’t have toured the way we did.”

Second album Killers was released in February 1981, and featured another new guitarist, Adrian Smith. Stratton had been ousted: according to Smallwood, “because Dennis liked The Eagles and wore red strides and the floppy white top. Sadly he just wasn’t very metal…”

Killers cost a little more than the first album – a still moderate £16,000 – but sold 750,000 units worldwide, including 150,000 in the USA. However, during the Killers tour in May, gigs in Germany were cancelled after Paul Di’Anno lost his voice. According to Harris: “Paul was totally fucked up.”

Di’Anno had always played fast and loose, but the band had no room for passengers. Touring was key to Maiden’s development, and as Di’Anno himself conceded, his rock’n’roll lifestyle was making him unreliable.

“It wasn’t just that I was snorting a bit of coke,” Di’Anno revealed. “I was going for it non-stop, 24 hours a day, every day. I thought that’s what you were supposed to do when you were in a big rock band. I knew that I’d never last the whole tour.”

It was a test of Harris’ leadership and Smallwood’s management. The search for a new singer began.

The first time Bruce Dickinson saw Iron Maiden play live was May 8, 1979 at the Music Machine club in Camden, where Maiden were the second act on a bill kicked off by Angel Witch and headlined by Samson, the band Dickinson later fronted. (The review of that gig, written by Geoff Barton and published a week later in Sounds, was the first time that the phrase ‘New Wave Of British Heavy Metal’ was used.)

As he watched Maiden from the back of the hall, Dickinson was convinced that this band was destined to become one of the biggest in the world. He also believed that he, and not Paul Di’Anno, should be Iron Maiden’s singer. “It was blindingly obvious,” he says, “that Maiden were going to be massive. This hyper kinetic band, it was really a force of nature. Paul Di’Anno, he was OK, but I thought, ‘I could really do something with that band!’”

Dickinson didn’t have to wait long for his chance. In the summer of 1981, he was approached by Iron Maiden behind Di’Anno’s back. Dickinson claims he “felt sorry” for Di’Anno, but he also sensed that Samson’s career was stalling. The band’s 1980 album Head On had reached the UK top 40, but the follow-up Shock Tactics, released in May 1981, had not even charted.

On August 29, Dickinson met Harris and Smallwood backstage at the Reading Festival after Samson had played. A few days later he went into the studio with Harris and laid down some vocals on a couple of key Maiden tracks so see how they sounded. He was a perfect fit.

Maiden had two Swedish shows lined up in September (Dickinson: “It must have been like having bad sex with the missus and then having a great shag with somebody else and then going back to the missus”) and after these Di’Anno met with Smallwood and was dismissed.

The very next day Dickinson became part of Iron Maiden, changing back to his real name Bruce Dickinson (rather than the ‘Bruce Bruce’ of Samson).

Rod Smallwood says of Di’Anno: “He couldn’t handle the success. It was never much fun telling people they weren’t in the band anymore, but you don’t change singer at that point if there’s any doubt. Of course we’d prevail – the band was so good.”

At the time, however, Steve Harris wasn’t so sure. Dickinson was technically a better singer, but Di’Anno was a hero to Maiden fans. “We knew Bruce was good,” Harris says, “but he was very different to Paul, so you’re thinking, ‘Are people going to accept this? Well, they’ll have to!’”

Bruce Dickinson was officially announced as Iron Maiden’s new singer in early October 1981, and made his UK debut with the band at London’s Rainbow theatre in November 15 following five ‘bedding-in’ shows in Italy in late October.

The singer’s authoritative performance silenced the calls from Di’Anno loyalists and allayed any lingering fears in Harris. But for Dickinson, joining Iron Maiden left him heavily in debt. He and the other members of Samson had signed a contract with the band’s management company with a buy-out clause of £250,000.

“It was a ludicrous sum,” Dickinson says. “We’d only ever had about 30 quid a week out of the band. But we were bonkers, completely out of our gourds, and we’d signed the document.”

Smallwood disputes the figure of £250,000, dismissing Dickinson’s arithmetic by laughing, “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing!” But it was Smallwood and Dickinson’s negotiating skill that resulted in a final settlement of £30,000, paid by Sanctuary Management on the understanding it would be repaid later.

It was still a lot of money, a daunting amount for the then 23 year-old. But Dickinson had never lacked confidence. He’d always believed that Iron Maiden, with him, would sell millions of records. And this was an opinion shared by the band’s producer, Martin Birch. During the recording of Iron Maiden’s third album, The Number Of The Beast, Birch told them, “This is going to be a big, big album. This is going to transform your career.”

In February 1982, six weeks before the album’s release, the single Run To The Hills entered the UK top 10. But on March 16, when Maiden’s Beast On The Road tour reached Newcastle City Hall, came the first serious argument between Harris and Dickinson.

Prior to that evening’s gig, the band had been at the venue for 12 hours, shooting a video for the new album’s title track. “We hadn’t had much sleep,” Dickinson says, “and we were all full of piss and vinegar.”

In a scene worthy of This Is Spinal Tap, a row developed between Harris and Dickinson over the singer’s microphone stand. According to Dickinson, “Steve kept standing at the front of the stage in the middle, sticking his chin right in my face while I was singing. And I thought, ‘I’m the singer, I stand at the front of the stage in the middle! When I’m not singing, you can stand there. But when I’m singing, I fucking stand there!’ I put extra long legs on my microphone stand so he would trip over them, and he went fucking spare!”

Harris now plays down the incident: “It might have put my nose out of joint for five minutes,” he admits,” but then I thought to myself, ‘That’s bloody good, it’s exactly the attitude you want from a frontman’.”

But as Bruce remembers it: “Steve was shouting, ‘I want him fucking gone, I can’t stand him!’ And Rod, to be fair, said: ‘He’s not fucking going! So get used it.’ And then we all calmed down.”

Both men laugh about this story now, but this was the beginning of an intense rivalry between them.

“Yes, it was Steve’s band,” Dickinson says. “But I had my own ideas. And I did warn everybody about it before I joined.”

However, if Dickinson was a pain in the arse, it was for Harris a price worth paying. The Number Of The Beast represented a huge leap forward for Iron Maiden. On songs like Run To The Hills, Children Of The Damned, 22 Acacia Avenue, Hallowed Be Thy Name and the title track, Iron Maiden finally sounded as Steve Harris had always envisaged.

In April 1982, The Number Of The Beast hit No.1 in the UK. The album had been recorded in just four weeks at a cost of £28,000.

“We had no record company advance whatsoever,” Smallwood reiterates. “So EMI’s total investment in that album was 28 grand, and in the first six months it sold 1.5 million.”

As Dickinson recalls, “What happened with The Number Of The Beast was beyond all our wildest dreams.”

On the day the album went to No.1, the band went to the Marquee to celebrate, where Harris had to ask Smallwood for extra cash to buy drinks for their friends. Only then did he increase their wages to £100 a week. The band didn’t need much money. They were on tour until the end of that year, living out of hotels, subsisting on tour catering. But when they returned home at Christmas, they received their first big paycheck.

During the summer Andy Taylor rejoined Smallwood to oversee Sanctuary and band’s business affairs. He and Smallwood had effectively become business partners at Trinity, Cambridge in 1969, Smallwood taking care of the creative side and Taylor the business. With the original three-album contract with EMI expired, Taylor soon secured a much improved deal with future advance royalties and royalty percentages based on the very healthy sales of The Number Of The Beast.

“We were always careful that we were set up properly financially,” says Taylor. “You get a big cheque, but at that point income tax was 60 per cent.”

Smallwood finally claimed his commission. “The band,” he says, “owed me a lot of money when we renegotiated.”

All of the band members bought houses. Dickinson put down a 50 per cent deposit on a place in Chiswick and cleared his debt to Sanctuary. But after a few days at home, Dickinson’s mood had taken an unexpected turn.

“To be honest, I was actually quite depressed,” he says. “I was in a great band, I’ve got a number one album, I’ve just done a world tour… What do I do with the rest of my life?”

Steve Harris felt quite the opposite. “I never thought, ‘Oh well, we’re at the top, this is it’. I wanted more and more.”

As Iron Maiden’s popularity rose via a series of hit albums, so Smallwood and Taylor started building a music industry empire on their proceeds. In 1984, Sanctuary began managing other artists – first W.A.S.P., later Helloween and Skin – and expanded into other areas of the music business with booking agency Fair Warning (with agent John Jackson), business management, licensing, merchandise and Platinum Travel.

As Smallwood puts it: “Andy Taylor later invented the ‘360-degree’ business model, effectively creating the mould used by the music industry today. This was the start.”

Iron Maiden was the engine that drove the expansion of the Sanctuary Group. But the band’s success created its own problems. Their working schedule was punishing. As Smallwood now reflects: “We did an album every year and a world tour. Fuck knows how we did it!”

And it was after the aptly named World Slavery Tour – comprising 192 dates, begun in August 1984 and ending in July 1985 – that an exhausted Bruce Dickinson again succumbed to depression.

“I came very close to quitting,” he says. Steve Harris remembers that tour as tough, and especially so on Dickinson. “Two hours of Maiden five nights a week for 12 months – that’s enough to put anyone in the funny farm! And Bruce, because he was singing, was completely fried.”

But it was only when the band began writing for their 1986 album Somewhere In Time that Harris realised just how much that tour had taken out of the singer. “The stuff Bruce was coming up with wasn’t us at all,” Harris says. “He was away with the fairies, really.” None of Dickinson’s songs would be included on the album.

“I did feel slapped down,” Dickinson admits. “I thought, ‘Well, I’ll take my paycheck and just do a good job singing’. But I wasn’t happy. I needed more. I wanted to be creating.”

With the following album, 1988’s Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, Dickinson had far greater input, co-writing four songs. He recalls: “When Steve said he had an idea for a concept album I went, ‘Yeah!’ It was brilliant. We were back and firing on all six – kerpow!”

Revitalised, Dickinson then recorded a solo album, Tattooed Millionaire, featuring former Gillan guitarist Janick Gers, who would subsequently join Iron Maiden in place of Adrian Smith. He also had his first novel published in 1990: a comic caper, The Adventures Of Lord Iffy Boatrace, but he denies that he was losing interest in Iron Maiden at that stage.

On the contrary, he claims that he alone sensed that the band’s next album, No Prayer For The Dying, was lazily executed. “We had a laugh making that album,” he says, “but I had this needling feeling: ‘Shouldn’t we be taking this just a bit more seriously?’”

Ironically, the least serious track on that album was Dickinson’s own Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter, which gave Maiden a No.1 hit in January 1991. The follow-up album, Fear Of The Dark, also topped the UK chart in 1992. But in an era when grunge was threatening rock’s old guard, and when Metallica were redefining metal with The Black Album, Dickinson felt that Maiden had lost their edge.

“I thought we should be a bit more dangerous,” he says. Dickinson found an outlet for his frustrations in making a second solo album. “It was about needing a challenge. But as I tried to make that album I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do.”

He was at a crossroads. “I wasn’t happy with the idea of being a cog in a successful, well-oiled machine. My life was like Groundhog Day, albeit gold-plated Groundhog Day. And I realised that the only way I’d find out whether or not I was any good was if I stepped outside my comfort zone. And the only way I could do that was by leaving the band.”

The singer exited Iron Maiden on August 28, 1993, at the end of a European tour.

Rod Smallwood, with typical bravado, now puts a positive spin on Dickinson’s departure. “When he told me I didn’t argue that much. It was good for us. It refocused things. Metal was heading towards another downturn with the advent of grunge, and all the hair bands on MTV had given real metal a bad name.”

Steve Harris remembers it differently. “It was a real downer when Bruce left. But then the attitude was: ‘Bollocks – we’ll pick ourselves up and get on with it’. That’s all you can do.”

Dickinson’s replacement was Blaze Bayley, formerly of British metal band Wolfsbane. For Bayley, joining Iron Maiden was a godsend: he was broke, and Wolfsbane had struggled since being dropped by Rick Rubin’s Def American label. But in truth, Bayley was never cut out for a big-league band such as Maiden. A great frontman, and a hugely likeable personality, Bayley just didn’t have the range to sing the classic Maiden material. And the two albums he recorded with the band – The X Factor in 1995, and Virtual XI in 1998 – are the weakest in the Maiden catalogue.

In Dickinson’s absence, Iron Maiden endured a long lean period. Smallwood concedes: “People were looking elsewhere. Nirvana and Pearl Jam were in. We just got on with the job.” Harris claims, “We still did really well, fantastically well in the circumstances.” But this is really his pride talking. With Blaze Bayley, Iron Maiden went into a steep decline.

In contrast, the Sanctuary Group was thriving. Taylor’s ‘360-degree’ model had captured the City’s imagination, leading to a full listing of the entire group on the London Stock Exchange in 1998. After the sale, Taylor and Smallwood each owned 20 per cent of the firm. Taylor was named Chairman and CEO dealing with the City, and Smallwood was head of music management. But Iron Maiden remained Smallwood’s priority, and in late 1998, with the band’s career stagnating, he delivered an ultimatum to Steve Harris.

“At the end of the day, Blaze wasn’t what was required for Iron Maiden,” Smallwood says. “If you build a legend like Maiden, you’ve got to keep it a legend. It’s my job as manager to make sure everything’s the best it can be in every possible way. And in the end, Steve accepted that.”

Smallwood and Harris recall that discussion differently. According to Smallwood, Harris was at first resistant to the idea of bringing Dickinson back into the band.

“Steve’s a very strong character and he takes things personally,” Smallwood says. “He needed time to think about that.” After all, Dickinson had walked out on Iron Maiden and left the other band members feeling betrayed. Nicko McBrain, the drummer who replaced Clive Burr in Maiden in 1983, noted on Dickinson’s departure: “He’s said, ‘Fuck you, I’m off’. If that ain’t shitting on you, then what the fuck is?” But after five long, hard years with Blaze Bayley, the simple truth remained: Iron Maiden needed Bruce Dickinson. And he needed Iron Maiden.

Since 1994, when he released Balls To Picasso, the album he’d begun while still in Iron Maiden, Dickinson’s solo career had been prolific but unspectacular.

“I had what you could call a global cottage industry,” he says. “I’d sold a few hundred thousand albums. I could have carried on, made a living out of it. But when I started getting smoke signals from the Maiden camp, my guitar player Roy Z said, ‘The world needs you back with Iron Maiden.’ And I said, ‘By God, Z, you’re right!’”

Blaze Bayley was summoned to Smallwood’s office. He recalled: “I was told my services were no longer required.” Bayley remains diplomatic. “I have no bad feelings about it. I liked Iron Maiden before I was in the band, and I still like them now.”

For Bruce Dickinson to rejoin Iron Maiden in 1998, Steve Harris had to be persuaded that he and the singer could reconcile their differences. Says Smallwood: “You cannot convince Steve of anything he’s unhappy with.”

Smallwood chaired a meeting at his home in Brighton, attended by Harris, Murray, Gers, McBrain and Dickinson. As the latter recalls, “Steve was very defensive at first. ‘Why are you doing this?’ I said, ‘Because we could make a bloody great comeback album that knocks people’s socks off, and I know we can do that.’”

Harris was cautious. “I didn’t want him coming back and just going through the motions,” he says. “But my gut instinct was that it was the right thing to do.” Tellingly, he adds: “Bruce was really irreplaceable.”

Says Smallwood: “Sense prevailed.”

It was the shortest meeting of Iron Maiden’s entire career. Three minutes in total, then off to the local boozer, where it was agreed that Adrian Smith would also rejoin the band in a new three-guitar line-up.

Maiden toured in 1999, to bigger audiences than in the previous four years, and in 2000 came Brave New World, which went gold in eight countries, by far outselling The X-Factor and Virtual XI. Iron Maiden’s career was reignited. But a couple of years after Dance Of Death’s 2003 release, the Sanctuary Group was running into problems.

Matthew Knowles, father of Beyoncé and manager of Destiny’s Child/Beyoncé, was made an executive of Sanctuary Records following the purchase of his management company. But when albums by Urban acts like De La Soul and D-12 were delayed, the parent company incurred heavy losses. US expansion was difficult and costly.

Rod: “Most parts of the company did extremely well – the Agency and Merchandising were thriving and the management group oversaw the careers of some of the biggest acts on the planet at the time [Elton John, The Who, Beyonce, Guns N’ Roses, Slipknot, Robert Plant, James Blunt] and Sanctuary Records UK via Rough Trade had signed new acts like The Strokes, The Libertines and Arcade Fire.

"The acquisition of Castle [and other labels brought] a huge catalogue of classic rock and reggae. The trouble is, when you’re a public company, if you have a bad period – which we did in America with sales diminishing against expectations – we had to issue a profit warning. And once you get a profit warning, all your competitors are saying, ‘You can’t do a deal with them because you never know if they’re going to be here tomorrow’. So it’s tough to do new deals.”

Taylor refutes the notion that Sanctuary over-expanded. “With a PLC, you’ve got to expand because the City expects to see growth. And we were unlucky – things hit at a bad time in the US.”

Bruce: “The tragedy was that in actual fact the ideas that they had were 100 per cent correct. I hate to use this business jargon, but their 360-degree model was absolutely the right thing to do. You can’t rely on record sales anymore to sustain a band. So if you’re signing a band, you have to be able to use everything at your disposal – including live, merchandising, everything. The idea of Sanctuary was that it contained all of that.”

Trading losses and write-offs in 2005 led to a major restructuring of the Sanctuary Group. By the end of 2006, Smallwood and Taylor had left the company, both men subsequently forming a new company, Phantom Music, with the intention of managing only Maiden. Rod says: “My priority before and during the time Sanctuary was a public company was always Maiden.”

Iron Maiden remains one of the biggest rock acts in the world. Steve Harris says Maiden will continue “as long as possible, as long as we’re still cutting it”. He was always determined, he says, that Iron Maiden should finish their career at the top.

Steve Harris and Bruce Dickinson have learned to live with each other for the greater good. “We still have had the odd argument,” Harris says, “but people grow up. We’re wiser. Age ain’t on our side. I remember being 12 or 13 and thinking that sixth formers with beards looked really old. And I think to myself, what do 14 year-old kids think of us now? They must think we look like bloody Gandalf! But it doesn’t matter – not unless you’re in the first 10 rows! We’ve had a fantastic life and career. If it stopped tomorrow, I’d die with a smile on my face."

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 159.