Four years. That’s all it took Jimi Hendrix to tear up guitar culture, depose the ruling elite and drag a centuries-old instrument in a thrilling new direction. Perhaps, on some level, the guitarist knew the clock was ticking. It would certainly explain the fervour with which he blazed through London after stepping off the plane at Heathrow on September 24, 1966.

Early sightings of this mysterious newcomer filtered back to the kings of London’s guitar scene. Hendrix, it seemed, was everywhere. On his first evening in the capital, he performed an eye-popping jam at the Scotch Of St James club. A few days later, depending on which source you believe, he was at the Cromwellian or back at the Scotch to jam with Brian Auger And The Trinity. “Our jaws dropped,” Auger recalls as the guitarist dialled a Marshall amplifier into the red for a feedback-soaked Hey Joe. Then on October 1, he even upstaged Eric Clapton, pulling out a double-time Killing Floor during a rocket-fuelled Cream cameo at the Polytechnic Of Central London. “You never told me he was that fucking good,” muttered the man known as ‘God’, nursing an insecure cigarette in the wings.

The buzz was deafening, but if Hendrix’s guitar revolution had a flashpoint, it was the Experience’s showcase at the Bag O’ Nails in Soho. Before a packed house of British luminaries – among them Clapton, Brian Jones, Pete Townshend, Jimmy Page and John Lennon – the American’s visceral display shuffled the hierarchy, prompting a tearful Jones to exit the club in a daze, and Townshend to later admit the experience “completely destroyed” him. Speaking to this writer, Queen’s Brian May agreed that witnessing Hendrix at full-throttle prompted one of two reactions: “As a guitarist, it really did make you want to give up. Or else go away and rip everything up.”

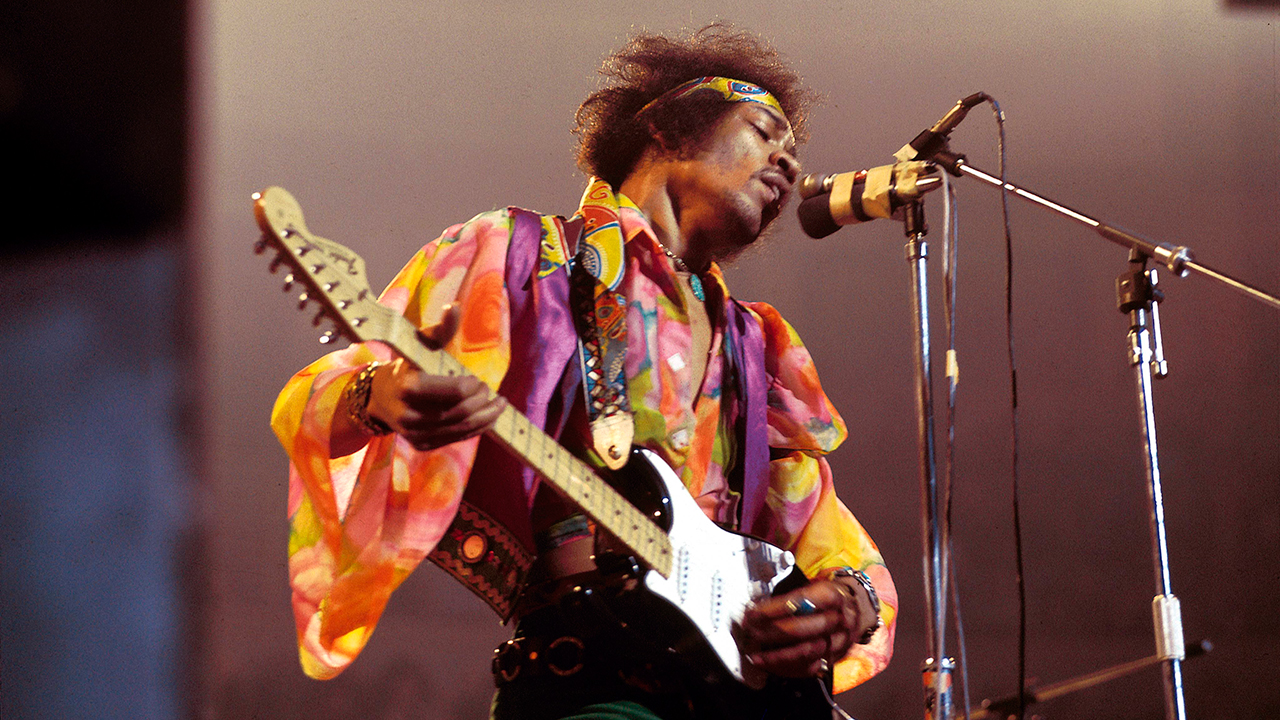

Hendrix blew all your senses. Before he even played a note, he began transforming the aesthetic of rock’n’roll, rewriting the perception of how a guitar hero should look. By the time he took the stage for 1969’s Woodstock performance, resplendent in pink bandana and white tasselled jacket, his status as the ultimate guitar icon was unassailable. It’s surely no coincidence that shortly after Jimi broke cover, Clapton would get his hair permed.

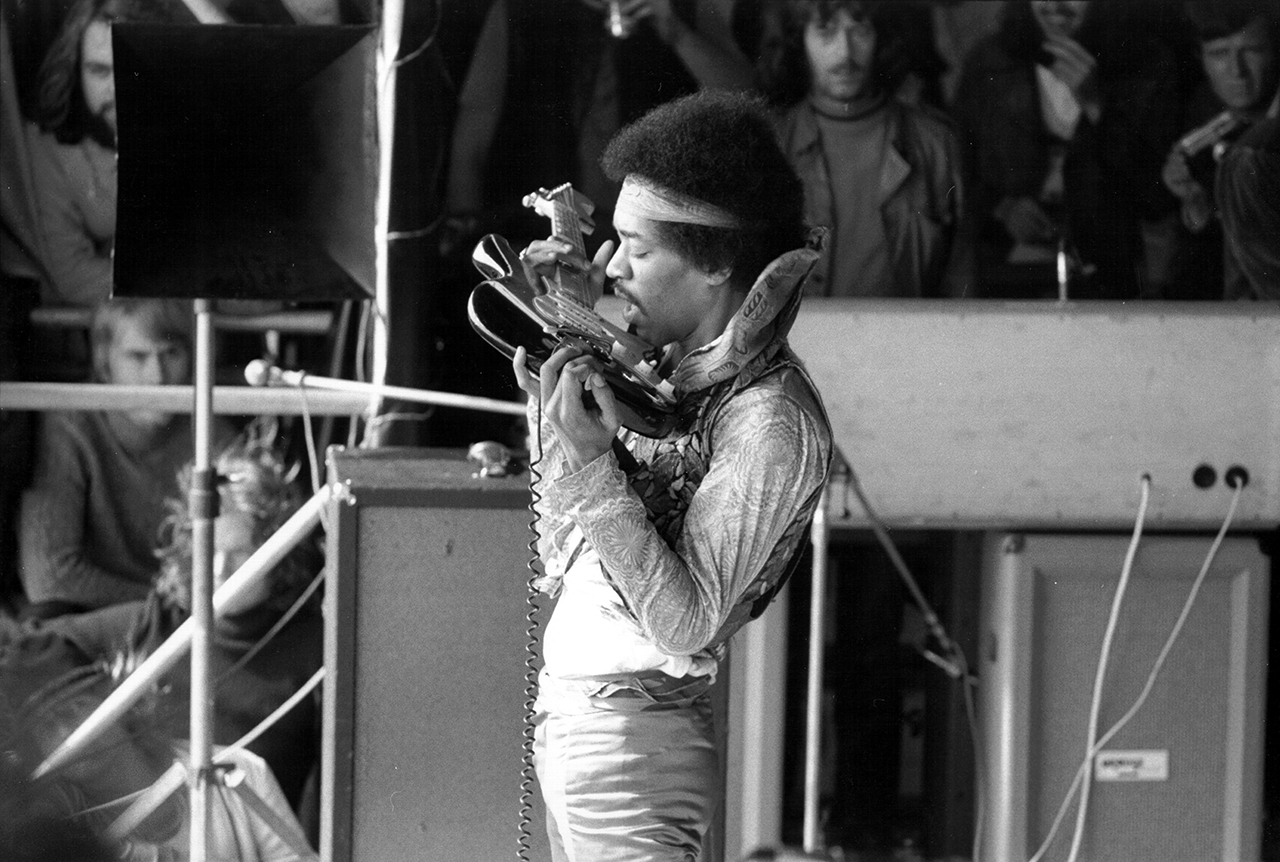

And yet, the magazine covers and hall-of-residence posters don’t do Hendrix justice. It wasn’t just how he looked that spelled revolution; it was how he moved. In the mid 60s, other guitarists were creating kinetic energy – witness Pete Townshend in full-flight with The Who – but Jimi stretched the concept of stagecraft to its outer limits. Mauling his Stratocaster’s strings with teeth and tongue, soloing behind his back, wrenching his whammy bar until the guitar slipped its tuning and, most notoriously, splintering and igniting his gear as a finale, Hendrix played with a physicality and irreverence that established the role of guitarist as equal parts musician, showman and rebel. As Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello puts it: “He made all those white-bread noodlers look like Cro-Magnon shoe-gazers by comparison.”

Those who didn’t throw in the towel were left attempting to unpick what Hendrix had that they didn’t. This was no small task. As a player, Jimi simultaneously defined his time while remaining curiously timeless, fusing past and future musical forms into a unique hybrid – then ramming it down the throat of the zeitgeist. The owner of a sprawling vinyl collection, his style was a melting pot of blues, rock, pop, folk, jazz and country, which sounded more colourful than ever at a time when most British guitarists were principally mining mothballed Delta blues.

“With our bunch of British guitar players,” agrees Auger, “you could still trace their roots in all the ‘King’ guys: B.B. King, Freddie King, Albert King, and Muddy Waters. They hadn’t really arrived at themselves. But Jimi Hendrix, man… He was something else. I don’t really have a name for it.”

Plenty of 60s players were accomplished, but most were specialists within their genre. By contrast, and from the neck-shiver of feedback that kicked off Foxy Lady on 1967’s Are You Experienced, Hendrix played with a vision that knew no limits. Here was a guitarist who could move from the squalls and white noise of Third Stone From The Sun, to the mellow piano-style ‘block’ chords of The Wind Cries Mary. He was an improviser who could drop jazz-inflected curveballs on late-period moments such as Pali Gap, or mint brand-new voicings on Angel and One Rainy Wish. He was also a lightning-speed soloist whose pull-offs and string skipping would later be hijacked by the heavy-metal mob and a pioneer who created the so-called ‘Hendrix chord’ (technically a dominant 7#9), and applied it to classics from Stone Free to Purple Haze.

His most groundbreaking motif was the ‘one-man-band’ style he picked up from Curtis Mayfield and Bobby Womack on the chitlin’ circuit of the early 60s, and developed to perfection on Little Wing. With his large hands, Hendrix was able to fret low-string parts with his thumb, while simultaneously playing a top-line melody, so creating a hybrid of rhythm and lead more often heard on piano. Utterly idiosyncratic, it’s a sound that has since been heard on everything from the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Under The Bridge to Pearl Jam’s Yellow Ledbetter. “I saw that he was playing with his thumb,” notes John 5, formerly of Marilyn Manson. “I still, to this day, always reach over and play with my thumb now.”

Even when Hendrix employed the pentatonic scale – that trusty go-to fallback of rock lead guitar – he’d twist the formula with left-field note choices and substitutions that shouldn’t work but did, creating flavours of sweetness, suspense or even pseudo-apocalypse. And he made it all look so easy. Where many modern shredders trade in robotic accuracy and clinical theory, Hendrix was the polar opposite: a precocious player whose technical brilliance appeared to tumble casually through him, as though his Strat was the antennae for some higher power.

“I was digging everyone from Muddy Waters to Eddie Cochran,” said Hendrix, when asked about his influences in 1968. “But I wasn’t trying to copy what I’d heard before.”

“He always played like a virtuoso that never practised a day in his life,” agreed Joe Satriani in Guitar Player. “You never heard a hint of a scale or exercise in what he played.”

As such, while the Hendrix catalogue is a musicologist’s dream, to analyse his output purely in dry, technical terms is to suck the joy from it and miss the point. Certainly, Hendrix didn’t approach guitar in terms of dotted minims and time signatures, but rather moods and atmospheres. “He spent his life trying to get sounds out of his head and express them on guitar,” Bob Hendrix, Jimi’s cousin, told Total Guitar. “He saw music in colours. In the studio, he would say, ‘This needs a little more red, or a little more blue…’”

To this end, and despite his enduring tendency to mutilate them, Hendrix’s guitars were his paintbrushes, and though he was spotted with Gibson’s Les Paul and Flying V models, his principal weapon of choice was the Fender Stratocaster. Still ubiquitous today, at the time, this 1954 design was a safe and somewhat unfashionable choice due to its associations with old-guard acts such as The Shadows, but in Hendrix’s hands, it became a magic wand, conjuring endless tones that contemporary players still chase, in vain.

When Hendrix slung a guitar, conventional wisdom and best practice had their noses tweaked. He would pick notes behind the nut, and fine-tune his volume control like a safe-cracker to locate the total sweet-spot. Though left-handed, he favoured a right-handed Strat strung upside-down (which subtly altered the tone), and while early models only allowed three tone choices, he would wedge the pick-up selector between settings, unlocking sounds that Fender’s designers hadn’t imagined (this doubtless prompted the company to overhaul the design in 1977). Throw in his habit of tailoring the height of his pick-ups to suit different flavours of feedback, and it’s not too much of a stretch to argue that Hendrix originated the 70s DIY boom that saw fans such as Brian May and Eddie Van Halen hand-build their first guitars.

Just as significant was Hendrix’s impact on amplifier trends, both sonic and aesthetic. Alongside Clapton, he was among the first wave of guitarists to employ volume as a vital ingredient in his sound, and is widely credited for developing controlled feedback as a melodic device, rather than mere novelty. Hendrix’s demands for decibels led to his patronage of the more-powerful amps built by Jim Marshall. Typically using a backline of souped-up, 100-watt Marshall stacks – that he compared to “two refrigerators hooked together” – Hendrix almost single-handedly raised the volume of rock, while establishing the supersized Marshall as obligatory stage furniture for at least the next two decades. “He became the greatest ambassador Marshall Amplifiers ever had,” Jim Marshall noted.

In the studio, Hendrix was a different animal again, immersing himself in production and pioneering the concept that a guitarist could do more than wait for the red light. Limited by the technology of the time, he nonetheless took the rudimentary four-track studios to the wire, treating the control room as an extension of his Strat, experimenting with backwards guitars, mic’ing techniques and modulation. “We were sort of dabbling in areas that had never been tried before,” engineer Eddie Kramer recalled in Total Guitar.

Particularly groundbreaking were his forays into the world of guitar effects – still a nascent industry in the late 60s. While most of his peers simply plugged direct from guitar into amp, Hendrix sought out the capital’s emerging engineering gurus, pressing for their latest innovations and fusing the new sounds into his material. Think Hendrix, and the first sound evoked is probably the fruity quack of the wah pedal. He wasn’t the only exponent – Clapton had used the effect on 1967’s Tales Of Brave Ulysses – but with Voodoo Child (Slight Return), Jimi created the defining statement.

“The huge thing that I got from Jimi Hendrix was his wah pedal technique,” says Metallica’s Kirk Hammett. “The first person I heard use a wah was Brian Robertson of Thin Lizzy, but then I started listening to more of Hendrix’s stuff and thought, ‘Wow, his wah technique is completely different.’ He made it very sleazy. He used it to get the wacka-wacka effect in that funky way, which was very cool, and fully got appropriated by a lot of session guitarists for the disco era that came ten years later.”

Wah was just the start. Since 1966, Hendrix had been a close associate of the engineer Roger Mayer, who would visit the studio during the Axis: Bold As Love sessions to deliver his bespoke pedals. “We’d talk first about what he wanted the emotion of the song to be,” Mayer told The Guardian. “He would talk in colours and my job was to give him the electronic palette which would engineer those colours so he could paint the canvas.”

Perhaps the greatest collaboration between the pair was 1967’s Purple Haze, on which Hendrix made masterful use of Mayer’s Octavia (a complex octave-doubling contraption that doubled the frequency of a note, adding the pitch one octave higher). “At the end of it,” explained Kramer, “the high-speed guitar you hear was an Octavia guitar overdub we recorded first at slower speed and then played back on a higher speed. The panning at the end was done to accentuate the effect you hear.”

Another sonic showcase was Band Of Gypsys’ live Machine Gun, fusing the sound of the Octavia, Univibe and Fuzz Face to approximate the sound of Vietnam. “My favourite Hendrix moment,” says Hammett. “It’s so atmospheric – he really brings you to the killing fields. Every time I hear that, the impending sense of doom he creates, it just blows me away.”

Of course, it’s maddening that Hendrix left us so soon. And yet, such is his all-pervading influence on guitar that it often seems he’s never been away. Cited as an influence by the most disparate of stars and voted to the top of best-guitarist polls by readers too young to have seen him first-hand, the sonic boom of his arrival keeps spreading ripples through the ages. Even now it’s almost impossible for a fledgling guitarist to pick up the instrument and not be influenced by him.

His enduring popularity confirms beyond doubt that the untouchable god of electric guitar is still on top of the podium, forever kissing the sky. “He’s definitely number one,” says Joe Satriani. “I think he’s the greatest innovator of the electric guitar that we’ve ever seen.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents Jimi Hendrix: People, Hell and Angels