Monday, August 4, 1975: another sweltering hot afternoon on the small Greek island of Rhodes. Maureen Plant, wife of Led Zeppelin singer Robert, is at the wheel of a rented Austin Mini, Robert beside her in the passenger seat, their three-year-old son Karac and six-year-old daughter Carmen in the back seat, along with their friend Scarlet, the four-year-old daughter of Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page.

Two months earlier, following Zeppelin’s record-breaking five-night run at the 17,000-capacity Earls Court arena in London, the young Plant family had set off for Agadir, in Morocco. Three weeks later they were in Marrakech where Page and his wife Charlotte and daughter Scarlet flew out to meet them. Together they took in a local festival “that gave us a little peep into the colour of Moroccan music and the music of the hill tribes”, said Plant.

From there they journeyed thousands of miles by Range Rover through the Spanish Sahara just as the Spanish-Moroccan war was breaking out. “There was a distinct possibility that we could have got very, very lost, going round in circles and taking ages to get out,” said Plant. “It’s such a vast country, with no landmarks and no people apart from the odd tent and a camel.”

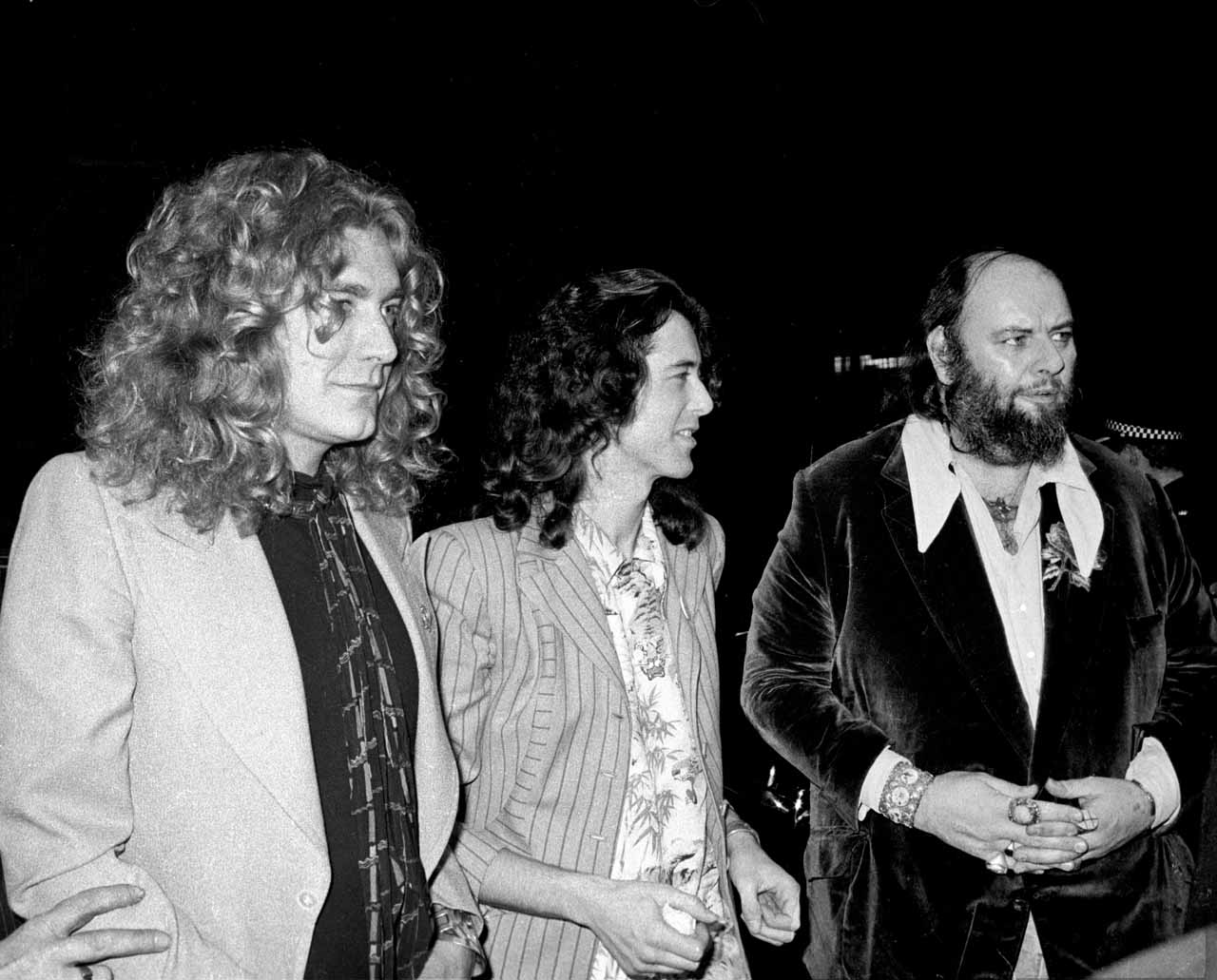

A month later, driving up through Casablanca and Tangier, they arrived in Switzerland for a meeting with Zeppelin manager Peter Grant at his lavish new base, renting promoter Claude Knobs’s house in Montreaux, and to spend a few days hanging out at the Montreux jazz festival, then in full swing. But by the end of July, Plant was getting itchy feet again, “pining for the sun [and] the happy, haphazard way of life that goes with it”.

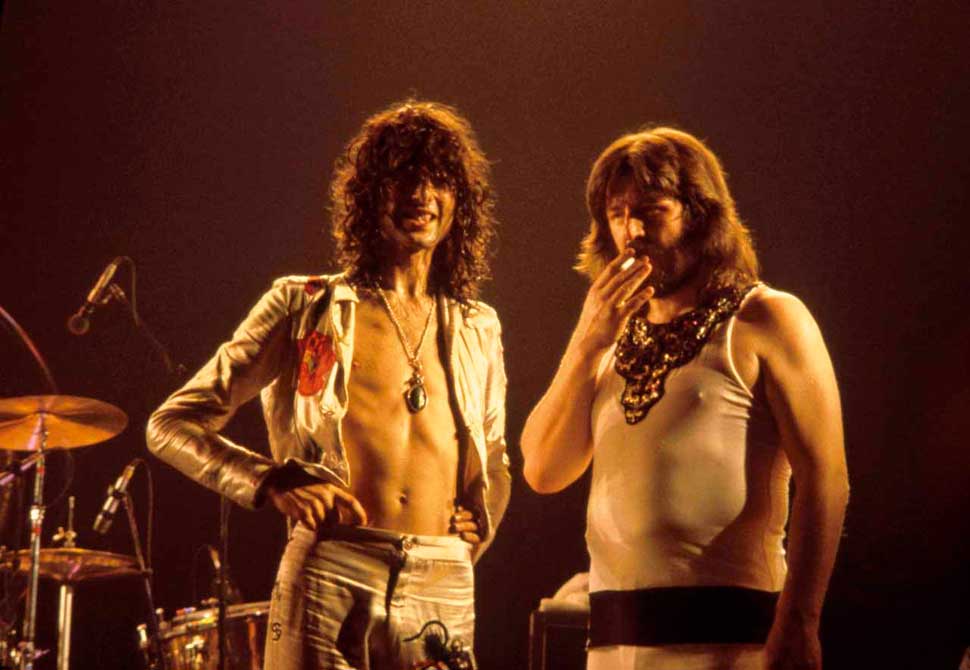

It was then that the idea of driving down to Rhodes came up. Plant arranged to meet Pretty Things vocalist Phil May and his wife, Electra, who had rented a house on the island from Roger Waters of Pink Floyd. Page, Charlotte and Scarlet followed in a second car, with Maureen’s sister Shirley and her husband.

On August 3, Jimmy left the party briefly to fly to Sicily to visit Aleister Crowley’s old Abbey of Thelema, which occult filmmaker Kenneth Anger had told him so much about and that he was now considering buying. The plan was to all meet up again in Paris a couple of days later where they would begin rehearsals for Zeppelin’s next US tour, scheduled to begin with two shows, already sold-out, on August 23 and 24 at the 90,000-capacity Oakland Coliseum in San Francisco.

Their most recent US tour had only ended in March, but with combined album sales and tour receipts estimated to have topped $40 million (more than $185m in today’s money) they were keen to keep momentum flowing. There was also the fact that they were now obliged to become tax exiles, unable to return to the UK for more than 30 days until April 1976.

Most of the ensuing period would be taken up touring the world, it was decided, affording the band unusual opportunities to travel to territories they had never been able to before – South America was seriously discussed, as was India, Africa and other previously thought out-of-the-way stops on the rock’n’roll map.

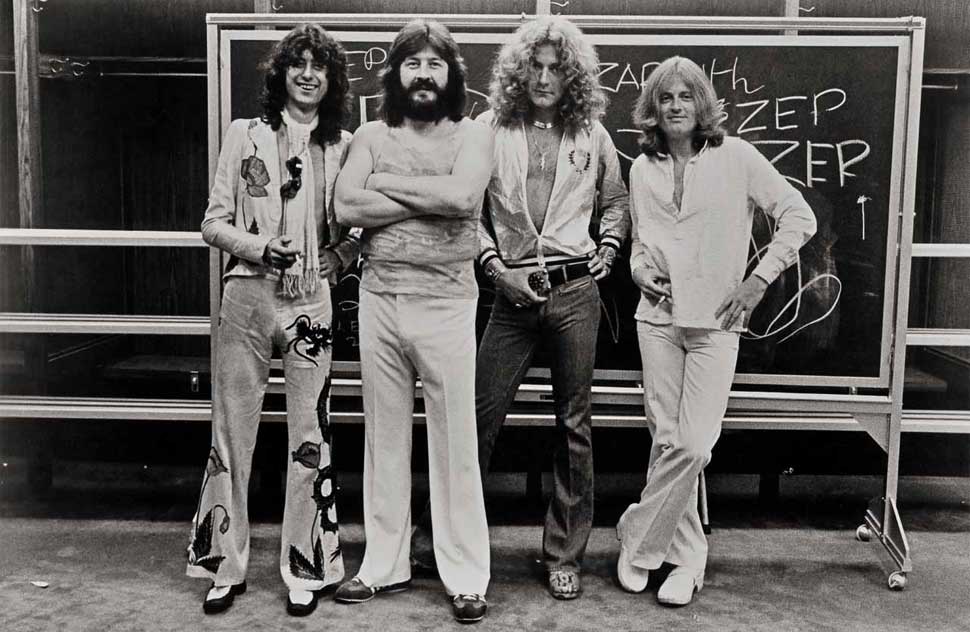

This was Led Zeppelin at the very top of the mountain, able to look down on nearest rivals such as the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd from a considerable height. Unstoppable, unbreachable, invulnerable, nothing could go wrong. Until suddenly it did. And nothing would ever be the same again.

Afterwards, nobody who was there could remember exactly what happened or why. Just that the car Maureen Plant was driving skidded and spun off the road, nose-diving over a precipice and into a tree. When Robert had landed on top of Maureen, the impact shattered his right ankle and elbow and snapped several bones in his right leg.

Looking at Maureen, who was bleeding and unconscious, he thought she was dead. The children were screaming in the back. Fortunately, Charlotte and Shirley, in the next car, were there to summon help, but it was still several hours before the family could be taken – on the back of a nearby fruit farmer’s flatbed truck – to the local hospital. There it was discovered that Maureen had suffered a fractured skull and broken her pelvis and her leg. Karac had also broken a leg, while Carmen had broken her wrist. Scarlet was the only one to escape with just a few cuts and bruises.

Maureen had lost a lot of blood, and because she had a rare type could only take Shirley’s blood for immediate transfusion. The process was painfully slow, with only one doctor on duty at the cockroach-ridden Greek hospital.

That night a hysterical Charlotte phoned Zep tour manager and all-round fixer Richard Cole in London, begging him to do something to get everyone home. Cole flew into action, furiously phoning round until he had co-opted two senior physicians – Dr John Baretta, a Harley Street specialist who also acted as medical consultant for the Greek Embassy and spoke fluent Greek, and Dr Mike Lawrence, a prominent orthopaedic surgeon – into journeying with him immediately to Greece.

It was still 48 hours before they arrived, though, and even then hospital officials refused to release the patients until a police investigation – searching for causes of the crash, specifically drugs – was completed, which might have taken weeks.

Again Cole saved the day. He hired a private ambulance and arranged for two station wagons to be parked at a side entrance, and wheeled Robert, Maureen and the children – their IV bottles swinging besides them – down to the getaway cars in the dead of night. Hours later they were in the sky heading back to London.

Their return home was delayed still further, however, this time, unbelievably, on the instructions of Zeppelin’s own record label’s accountants, who insisted Cole delay the plane’s landing by 30 minutes so as to avoid using up a precious day of Plant’s allotted tax-free time in the UK. Circling at 15,000 feet, Cole reflected that while it may have saved Plant thousands of pounds in taxes, “I still thought it was more important to save a life”.

When the plane finally touched down, the Plants were transported via waiting ambulances to Guy’s Hospital, where Maureen underwent immediate surgery. It would be several more weeks before she was well enough to leave. Robert, who was placed in a cast that ran from his hip to his toes, also faced sobering news from the doctors. “You probably won’t walk again for six months, maybe more,” he was told. “And there’s no guarantee that you’ll ever recover completely.”

It was debatable who took the news worst – Plant or Grant. “This could be the end of Led Zeppelin,” Grant complained to Cole. “This might be the end of the line.”

Jimmy Page was also devastated by the news. “I was shattered,” he said. He had “always felt”, though, “that no matter what happened, provided he could still play and sing, and even if we could only make albums, that we’d go on forever”. Robert’s fate, Jimmy had no doubt, was tied inextricably to that of the band. “Just really because the whole aspect of what’s going to come round the corner as far as writing goes is the dark element, the mysterious element. You just don’t know what’s coming. So many good things have come out of that, that it would be criminal to interrupt a sort of alchemical process like that.” He added: “There’s a lot of important work to be done yet.”

To make matters worse, to preserve his new tax-exiled status Plant would have to be moved out of the country again while his wife was still recuperating in hospital. Temporary accommodation was arranged for him on the island of Jersey (exempt from punitive British tax laws) at the mansion home of millionaire lawyer Dick Christian, who sent a limousine and an ambulance to meet Plant and his mini-entourage of Cole, Zeppelin soundman Benji Le Fevre and band PA Marilyn.

Christian kindly offered his guest the use of his Maserati and Jensen Interceptor cars, but a wheelchair-bound Plant would spend the next six weeks moping around the guest house, drinking beer and knocking back prescription painkillers. Occasionally he played the piano, but mainly he just sat and stared, his mood desperate. “I just don’t know whether I’m ever going to be the same on stage again,” he told Cole repeatedly.

Eventually it was decided that work was the best therapy. “The longer we wait,” Page complained to Cole, “the harder it’s gonna be to come back.” With the band’s ambitious touring plans put on indefinite hold, it was decided to get to work on the next Zeppelin album. By the end of September, Plant, his wheelchair and his crutches were being boarded onto a British Airways flight to Los Angeles, where Page was waiting for him in a rented beach house in Malibu Colony.

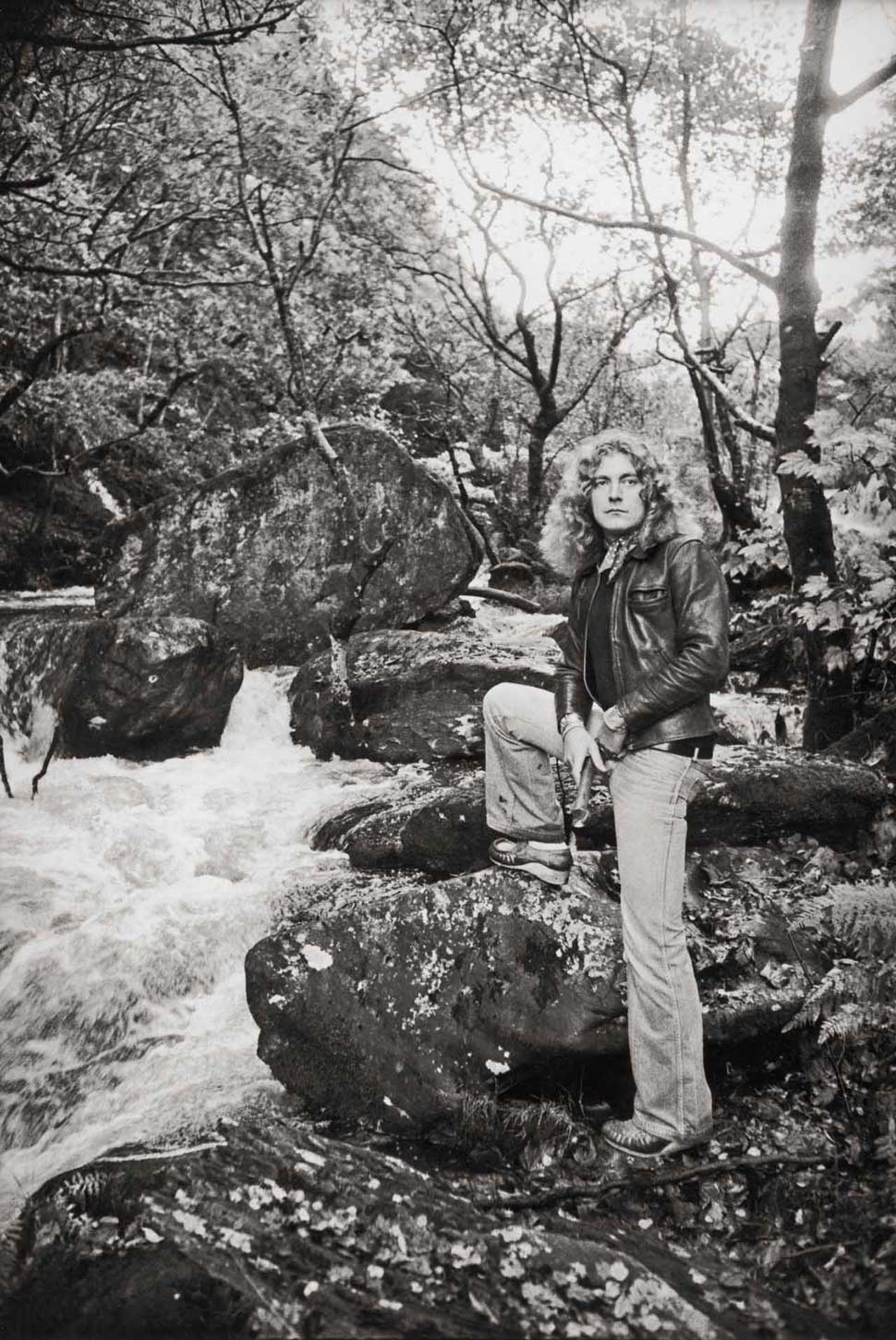

As with their stay at Bron-Yr-Aur five years before which produced the nucleus of the Led Zeppelin III album, the two planned to write together. There were no peaceful, flower-strewn valleys to enjoy this time, though, just the lights of old LA beckoning them onto the rocks.

Robert’s mood was still predominantly black but, hanging out with Jimmy, writing again, he now had good days as well as bad, taking short, therapeutic strolls along the beach with his new cane, before collapsing back into his wheelchair. There were also trips see Donovan perform at the Santa Monica Civic, and a catch-up with Paul Rodgers and Boz Burrell from Bad Company.

Jimmy also checked out his friend Michael Des Barres’s band Detective, offering them a deal with Zep’s label Swan Song. However, there was another factor about Plant’s Californian rehabilitation that wasn’t discussed: the plentiful supply of cocaine and heroin that Page’s presence anywhere now demanded. Also staying at the Malibu house was Benji Le Fevre, who told Cole they’d nicknamed the place “Henry Hall” – slang for heroin.

Having used up their backlog of material on Physical Graffiti, with the exception of the riff to the unreleased Walter’s Walk, which Page now reused to create Hots On For Nowhere, songs for the new album would have to be built from the ground up. One of the first to take shape was Achilles Last Stand, the lengthy opus that would eventually open the next album.

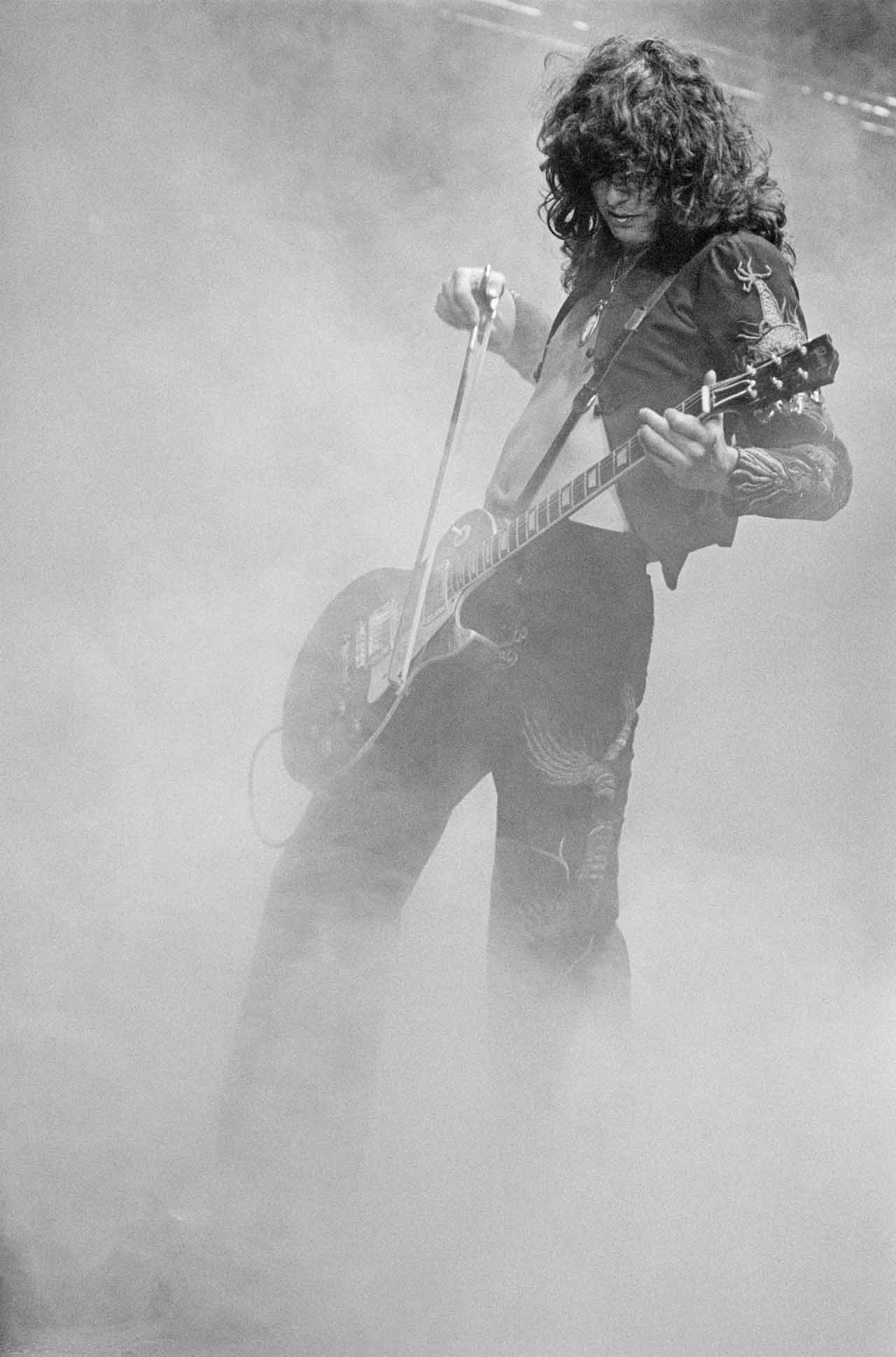

Built on the sort of strident, all-hands-on-deck guitar figure that Iron Maiden would later build a whole career out of – Page attempting to create something, he said, that reflected “the façade of a gothic building with layers of tracery and statues” – Achilles Last Stand also featured the first of a string of intensely autobiographical lyrics Plant now felt compelled to write.

Originally nicknamed The Wheelchair Song, the subject in this instance was the enforced exile which had forced the band to become what Page later described as “technological gypsies”, and led indirectly, Plant seemed to suggest, to their current malaise – ‘the devil’s in his hole!’ he wailed balefully. Page later described his guitar solo as “in the same tradition as the solo from Stairway To Heaven”. In truth, few would now agree but, “It is on that level to me,” he insisted.

Musically, Tea For One, the equally lengthy blues showcase that would close the album “was us looking back at Since I’ve Been Loving You,” Page would later tell me, “being in a very lonely space at the time and… you know… reflecting accordingly”.

Lyrically, it found Plant metaphorically wringing his hands, the loneliness of his separation from his wife and children – Maureen being still too ill to travel – juxtaposed against the artificial luxury of his drug-fuelled life in Malibu. “I was just sitting in that wheelchair and getting morose,” he recalled. “It was like… is this rock’n’roll thing really anything at all?”

But that was as nothing compared to the venom he summoned up in For Your Life and Hots On For Nowhere: the former a vicious attack on the LA lifestyle he’d once eulogised, railing against ‘cocaine, cocaine, cocaine’ in the ‘city of the damned’; in the latter he directs his anger this time towards both Page and Grant, and their insensitivity to his situation, only concerned for their own futures, as he spits: ‘I’ve got friends who would give me fuck all…’ Seemingly oblivious to Plant’s ire, Page inadvertently colludes in the song’s bitter denouement, using the tremolo arm on a Fender Strat he’d borrowed from former Byrd Gene Parsons, to produce a resounding twang in the middle of his solo.

Naturally, there was also the by now almost obligatory pillaging of the blues, this time for a new cornerstone Zeppelin moment, another Blind Willie Johnson classic from 1928 called It’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine, here shortened to Nobody’s Fault But Mine.

Originally the story of Johnson fretting because his blindness prevented him from reading his bible, thereby incurring the wrath of God, it became a useful metaphor for Zeppelin’s own fiery descent from heaven, Plant adapting the lyrics to include some revealingly stuttering lines about having ‘a monkey on my back’ embellished by some suitably squalling harmonica. As usual, the only truly original parts were the strafing guitar lines Page concocted to which John Bonham added his most mercilessly cannon-like drum pummelling since When The Levee Breaks.

It wasn’t all bleak. Candy Store Rock – its genesis traceable back to live performances of Over The Hills And Far Away where Page, Jones and Bonham would frequently drift off into a similarly paced improvisation – was a jolly enough romp, with Page making a rare recorded return to his rockabilly roots, and Plant cheerfully following suit, “being Ral Donner”, as he put it, “the guy who wanted to be Elvis”.

Royal Orleans – named after the hotel at 621 St Louis Street where Jones had had an unfortunate accidental encounter with a drag queen on the ’73 US tour – was another deliberate attempt to lighten the mood, its pleasingly staccato rhythms enlivened by the jokey lyric: ‘When the sun peaked through… he kissed the whiskers, left and right,’ and a jokey reference to talking ‘like Barry White…’

With most of the material finished by the time Jones and Bonham arrived at the end of the month, time originally booked at SIR Studios in Hollywood for writing and rehearsal was used mainly to finesse what Page and Plant had already come up with. Work described by Page as “gruelling” because, he said, “nobody else really came up with song ideas. It was really up to me to come up with all the riffs, which is probably why [the songs were] guitar-heavy. But I don’t blame anybody. We were all kind of down.”

In fact neither Jones nor Bonham were given a chance to participate. As Jones told Zep historian Dave Lewis in 2003: “It became apparent that Robert and I seemed to keep a different time sequence to Jimmy. We just couldn’t find him.” Jones added that he “drove into SIR Studios every night and waited and waited… I learned all about baseball during that period, as the World Series was on and there was not much else to do but watch it.” Even when recording for the album had begun, “I just sort of went along with it all”, he shrugged. “The main memory of that album is pushing Robert around in the wheelchair from beer stand to beer stand. We had a laugh, I suppose, but I didn’t enjoy the sessions, really. I just tagged along with that one.”

Hence the solitary co-writing credit Jones and Bonham receives on the album, for Royal Orleans. Even when Jones did manage to contribute some solid ideas – such as the bass line he created with his distinctive Alembic eight-string for Achilles Last Stand and which he describes now as “an integral part of the song” – it went unacknowledged. “What one put into the track wasn’t always reflected in the credits,” he observed dryly.

It’s clear that Presence was not one of Jones’s favourite Zeppelin albums. In truth it would rarely become anybody’s favourite Zeppelin album – except for Page, who still stubbornly rates it one of their best. As Dave Lewis says now: “It was the first album all over again, with Jimmy in total control of everything and hardly anyone else getting a say. That’s why there was no Boogie With Stu or Hats Off To Harper on that album, no Mellotrons, acoustic guitars or keyboards of any kind – no Jonesy! It was all Jimmy. No one else really got a look in.”

One person blissfully unconcerned with the niceties of songwriting at this point was John Bonham, whose enforced year away from home was beginning to have the anticipated effects. One night during the SIR sessions, he arrived at the Rainbow bar & grill, Zep’s favoured haunt on Sunset Strip, where he sat at the bar and ordered 20 black Russians (vodka and coffee liqueur), and polished off half of them in one go. Swivelling on his seat, he spotted a familiar face, Michelle Myer, long-time associate of producer and LA socialite Kim Fowley. Myer, sitting eating dinner, looked over and smiled. Bonzo did not smile back. Instead he went over and punched her in the face, knocking her off her seat. “Don’t ever look at me that way again!” he roared.

At the end of October, when the band finally left LA – Jimmy insisting they move at once, after an unusually thunderous storm which erupted over the Malibu coastline, which he took as a bad omen – they flew to Munich, where Musicland studios had been booked for them to complete the album.

On the flight, Bonzo knocked himself out on several large G&Ts, a couple of bottles of white wine and champagne, causing so much disruption that the other First Class passengers begged the steward not to wake him when the food was served. When he came to a couple of hours later he had pissed himself. He shouted for Mick Hinton, his personal roadie, and forced him to stand in front of him while he changed his pants. Then he made Hinton sit in his urine-drenched seat while Bonzo took Hinton’s seat in Economy.

Situated in the basement of the Arabella Hotel, Musicland was bright and modern, sparsely furnished, the accent firmly on the functional. The Rolling Stones were due in straight after Zeppelin. So tight was the scheduling squeeze that Zep had just 18 days to work in. No Zeppelin album since their first, seven years before, had been recorded so quickly, but Page was determined to make it work.

In the event, he would find himself calling Jagger, begging for more time. It was a request the Stones’ mainman was happy to acquiesce to – up to a point. He could let Jimmy have three extra days, he said. Hardly any time at all in recording terms, but it was all Page needed to finish the job, laying down all his guitar overdubs in a frantic 14-hour session, including at least six for Achilles Last Stand, quitting only when his fingers ached so much he could no longer manipulate them properly.

Outside, Munich was in the grips of a bitterly cold winter; inside the studio it was permanent midnight, Jimmy staying up for three days at a time, then sleeping on the floor of the studio.

“The band did the basic tracks and then went away,” he recalled, “leaving me and [engineer] Keith Harwood to do all the overdubs. We had a deal between us: whoever woke up first woke up the other one and we’d continue the studio work.”

As a result, Page remains inordinately proud of what at the time he initially referred to as simply “the Munich LP”, its final title undecided until the cover had been finalised.

“It was a very, very intense album,” he would recall, “Robert had had the accident, and we didn’t know how he was gonna heal. He was on crutches, and singing from a wheelchair.” Or as Plant said at the time, it was “our stand against everything. Against the elements and chance…”

Only once during the Munich sessions did the weird momentum Page had created threaten to unravel, which was when Plant, still in plaster, pulled himself up from his wheelchair one afternoon to stretch, lost his balance and fell onto his bad leg, and a horrifyingly loud cracking sound filled the room.

“Fuck!” he screamed. “Not again! Not again!” First to reach him was Page, petrified that Plant had broken his leg again. “I’d never known Jimmy to move so quickly,” Robert later recalled laughingly. “He was out of the mixing booth and holding me up, fragile as he might be, within a second. He became quite Germanic in his organisation of things, and instantly I was rushed off to hospital again in case I’d reopened the fracture.”

So worried was Page, in fact, that no more work could be done that day. Fortunately, after a call later that night confirming no further injury, Jimmy was back in the studio, putting in another all-nighter.

The album was finally finished on November 27, the day before Thanksgiving in America that year. The following morning, while Page was still sleeping, a delighted – and relieved – Plant put a call to the Swan Song office in New York to give them the good news, even suggesting they call the album Thanksgiving.

A week later the entire band were back in Jersey, where, on December 3, Bonham and Jones made an impromptu appearance on stage with Norman Hale, resident pianist at local watering hole Behan’s Park West and a former member of 60s chart toppers The Tornados.

A week later the whole band joined Hale for a surprise 45-minute set at the club, where fewer than 300 people watched the band tear through their “Eddie Cochran and Little Richard repertoire”, as Plant put it. “I was sitting on a stool, and every time I hit a high note I stood up but not putting any weight on my foot.” By the end of the set, Plant was “wiggling the stool past the drums and further out. Once we got going we didn’t want to stop.”

In Paris three weeks later, celebrating New Year’s Day, Plant took his first steps unaided since the crash five months before. “One small step for man,” he joked, “one giant leap for six nights at Madison Square Garden…”

In January 1976 the whole band were in New York, staying at the Park Lane Hotel on Central Park South. While Page began tinkering again with the mix of the live soundtrack to the long-delayed “road movie” which would later become The Song Remains The Same, Plant was hitting the town in the company of Benji Le Fevre and an English bodyguard called David. Although the plaster cast had now been removed, he still walked with a cane or crutch.

Less conspicuously but more worryingly, Bonzo was also intent on getting the most out of his enforced stay in the city. When Deep Purple arrived in town for a show at Nassau Coliseum, a drunken Bonzo walked on stage in the middle of their set, grabbed a free mic and announced: “My name is John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, and I just wanna tell ya that we got a new album comin’ out called Presence and that it’s fucking great!” Then he turned to Deep Purple’s guitarist and said: “And as far as Tommy Bolin is concerned, he can’t play for shit…”

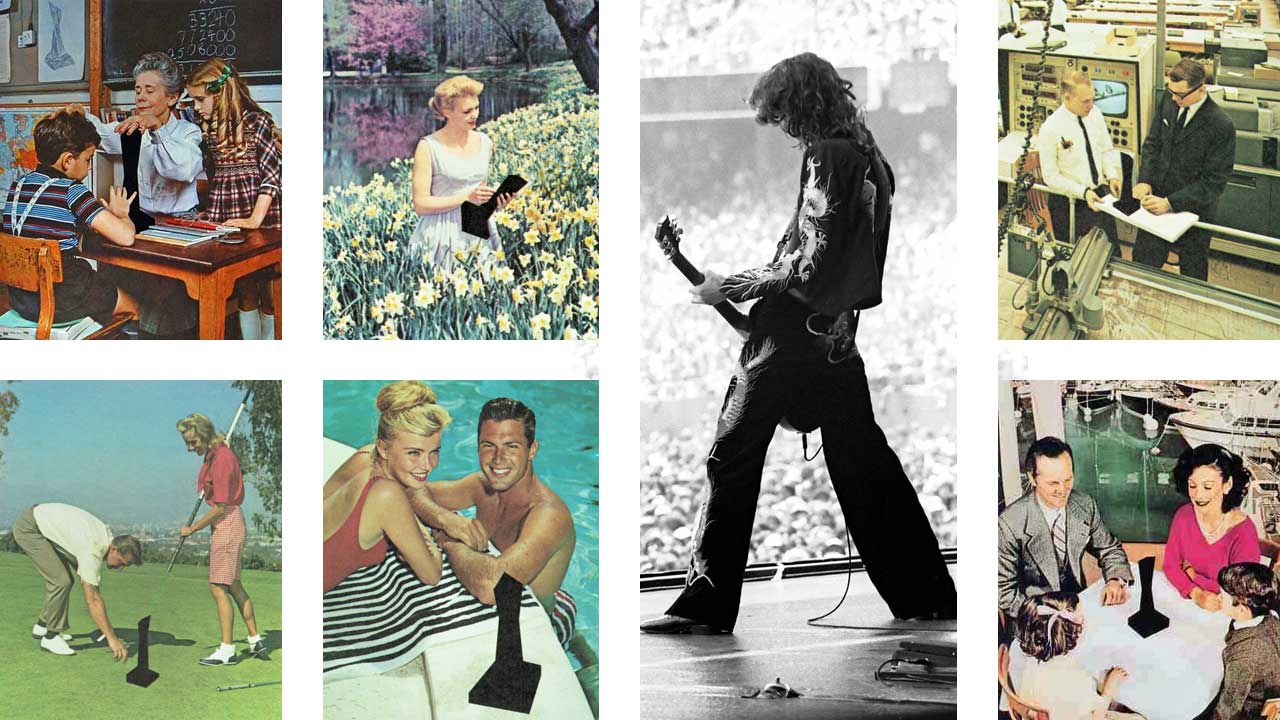

The album’s eventual title, Presence – irritatingly revealed ahead of time by Bonzo – was inspired by the sleeve it came in, a typically incongruous Hipgnosis creation, from an idea Storm Thorgerson, Aubrey Powell and friends Peter Christopherson and George Hardie (who had worked on the first Zeppelin sleeve) were already tinkering with.

Reminiscent of the sleeve the same team had come up with the year before for Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here (which included images of two suited businessmen shaking hands, one of them on fire, a swimmer front-crawling through sand and others of an ilk), the front of Presence was a photograph of a ‘normal’ family (mum, dad and 2.2 children) seated at a restaurant table. Positioned at the centre of the white tablecloth is not a candle, as might be expected, or some floral arrangement, perhaps, but a twisted black oblong shape mounted on a plinth, dubbed ‘The Object’ by Hardie and co.

In the background to this central image, shot in a studio in Bow Street, London, are photographs from that year’s Earls Court Boat Show. The rest of the gatefold sleeve includes similarly contrived images: on the back of the outer-sleeve, a schoolgirl (modelled by Samantha Giles, previously one of the children on the Houses Of The Holy sleeve) is seen with her teacher and another pupil at a desk on which stands another image of The Object. Eight more similarly enigmatic images (many taken from the archives of Life and Look magazines)furnish the inner sleeve, while the inner sleeve containing the vinyl carried unvarnished images of The Object on its own.

Later copyrighted by Swan Song, the object in question was a 12-inch black obelisk, designed by Hardie as “a black hole” then completed by model maker Crispin Mellor. It was nicknamed “the present”, says Hardie, as “a play on the fact that the actual object – a hole, in fact – wasn’t present at all, but absent.”

Storm Thorgerson recalled “contaminating” the deliberately dated images with what he describes as “the black obsessional object”, which he maintained “stands as being as powerful as one’s imagination cares it to be… We felt Zeppelin could rightfully feel the same way about themselves in the world of rock music.”

According to Page “they came up with ‘the object’ and wanted to call [the album] Obelisk. I held out for Presence. You think about more than just a symbol that way.” And of course, the acknowledgement of a ‘presence’ had more occult resonance than a mere ‘object’. And unlike their previous two albums, this time they did allow the band’s name and the album title to appear on the sleeve, albeit embossed on the white sleeve, similar to The Beatles’ White Album. (The original UK shipment of Presence added a shrink-wrapped outer package with title and band name in black with a red underlined border. In the US the shrink-wrap also included a track-listing.)

To launch the album, Swan Song had 1,000 copies of the obelisk made which they planned to place simultaneously outside a wide range of iconic buildings across the globe, including the White House, the Houses Of Parliament and 10 Downing Street. The idea was not dissimilar to how, a year later, Pink Floyd would launch their Animals album by floating a giant pig over London’s Battersea Power Station. But the idea was cancelled when Sounds magazine got wind of it and leaked the news. Instead, models of The Object were eventually gifted to various favoured journalists, DJs and other media people, and are now highly collectable artefacts.

When Presence was released on March 31, 1976 it was another instant No.1 hit, going gold in the UK (platinum in the US) on advance sales alone, and becoming the fastest-selling album in the Atlantic Records group’s history.

Reviews were generally good too. John Ingham, in Sounds, called it “unadulterated rock and roll” and described Achilles Last Stand as the song to “succeed Stairway To Heaven”, while Stephen Davis, in Rolling Stone, said it confirmed Zeppelin as “heavy-metal champions of the known universe”. He add the caveat: “Give an Englishman 50,000 watts, a chartered jet, a little cocaine and some groupies and he thinks he’s a god. It’s getting to be an old story…” – a more piercingly accurate comment than even the writer probably knew.

But sales soon tailed off, just as they had for Led Zeppelin III and Houses Of The Holy, initial excitement failing to translate into wider general interest among non-partisan record buyers as what was – correctly – perceived as the album’s generally depressing ambience became known.

Undeterred, Page and Grant dismissed the lack of a strong following wind for sales of the album as a side effect of the band’s inability to promote it with a world tour. But the fact is that Presence remains one of Zeppelin’s least satisfying musical confections; the story behind it of more lasting interest than the often rather turgid music that resulted, despite the fact that both Page and Plant regarded it as a personal triumph.

“Against the odds, sitting in a fucking chair, pushed everywhere for months and months, we were still able to look the devil in the eye and say: ‘We’re as strong as you and stronger, and we should not only write, we should record,’” Plant told a reporter from Creem. “I took a very good, close scrutiny of myself, and transcended the death vibe, and now I’m here again, and it’s mad city again.”

Page’s affection for Presence was more to do with fond reminiscences of the nights he spent alone, with just recording engineer Keith Harwood for company, doodling away to his stoned heart’s desire, than with the end product in itself.

Not that Zeppelin’s overall popularity was particularly affected. Promoters, eager to tempt the band back onto the road, told Peter Grant that demand for Zeppelin tickets would be greater than ever – if and when the band decided they were able to return.

With time on their hands and interest in Presence flagging, plans were already in place for Led Zeppelin to make a full-on return to America the following year. When things would surely improve for the band. Wouldn’t they?