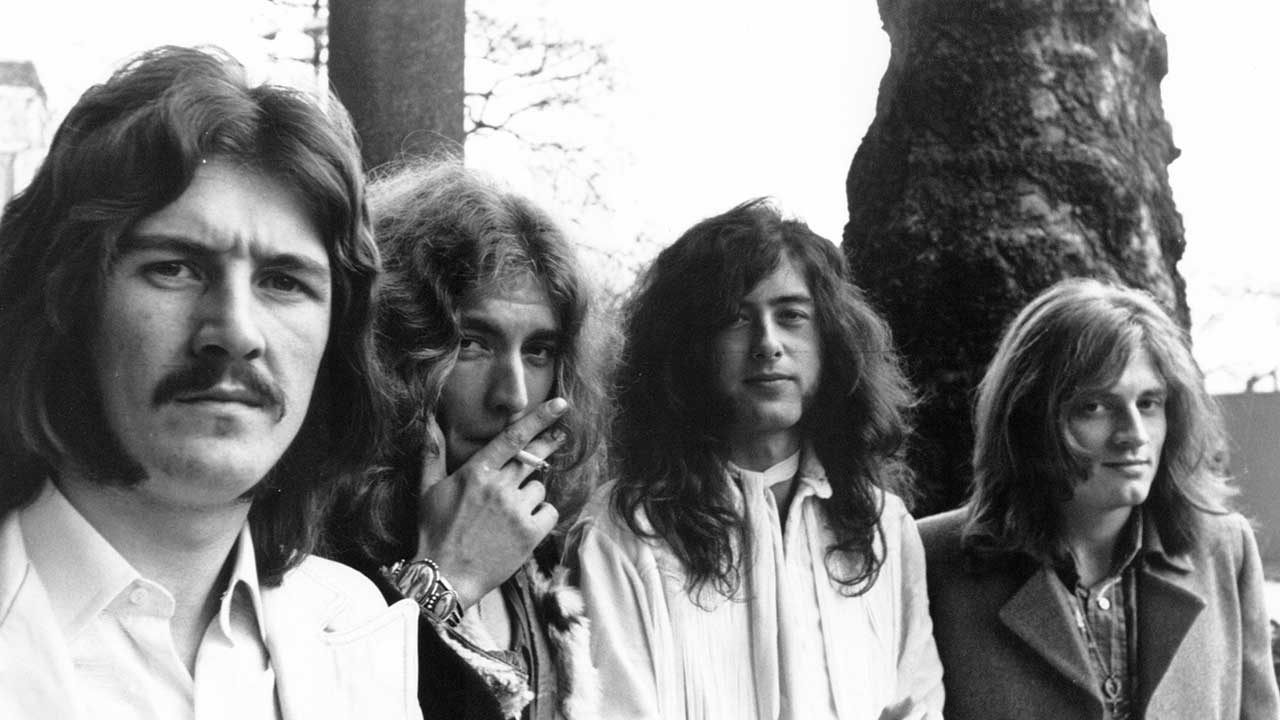

On 15 October 1968, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham appeared for the first time under the name Led Zeppelin. The gig was at Surrey University. Their set began with 12 bars of Train Kept A Rollin’.

They crashed through Communication Breakdown and I Can’t Quit You Baby before heading into a blues medley that started with Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor and then ran into an old tune called Fought My Way Out Of Darkness over which Plant sang the words, “squeeze my lemon til the juice runs down my leg” – words which were taken from a Robert Johnson tune called Travellin’ Riverside Blues.

In the middle of it all, Jimmy Page broke into a version of Elvis Presley’s That’s All Right, and Plant added the vocal line from Milt Jackson’s Bag’s Groove.

The set closed with an 11-minute take on Dazed And Confused, a folk song popularised by Jake Holmes and first played by Page in the Yardbirds under the title I’m Confused.

Three days later, the band played at the Marquee in London billed as the New Yardbirds, their original choice of name. ‘Good poets steal,’ wrote TS Eliot – and so of course do good musicians. And as Eliot went on, ‘the good poet welds his theft into something unique’.

From their very first gig, Led Zeppelin took what they wanted from the existing canon of music. And yet they repaid the debt by turning what they took into something more than the sum of its parts, something lasting. The blues songs that they played and recorded in their early years became the foundation for an entire genre of music; in reusing them and spinning them in new and unheard directions, Zeppelin were extending a tradition that had begun with blues and folk music itself.

Jimmy Page once said: “I’ve often thought that in the same way that the Stones tried to be the sons of Chuck Berry, we tried to be the sons of Howlin’ Wolf”.

He wasn’t the only young musician in London with a head full of other people’s records. Eric Clapton had been tutored by John Mayall for his gig in the Bluesbreakers and he took what he’d learned into Cream, the first supergroup. Jeff Beck had just made a record called Truth that referenced George Gershwin and Willie Dixon.

Jimi Hendrix had electrified London with his attempts to combine what he called “earth” (blues and jazz) with “space” (psychedelia). The Earth blues band would soon turn some chords from Gustav Holst’s Mars into a song called Black Sabbath. Ian Anderson’s Jethro Tull merged acoustic folk with blues riffs.

The London scene was fevered and organic. People were making albums that they thought might last for six months, not four decades. Record companies and music publishers had no concept of the revenue that such bands might generate.

“It was like the wild west,” one executive reflected. “No-one had any idea what might happen next week, let alone next year”.

Howlin’ Wolf, a figure much admired by this new wave, was himself a huge man, 6’6” tall and close to 300lbs. He brought some of that powerful physicality into his music. Albert King covered his song Killing Floor before Jimi Hendrix got hold of it. Hendrix took it one way, and Led Zeppelin took it another, playing it live many times before using it as the base for The Lemon Song on Led Zeppelin II.

The Robert Johnson lyric that Robert Plant used at Surrey University would appear on the recording too. It remains a perfect example of how rock music would first feed upon itself and then grow.

Led Zeppelin’s first album was recorded in 36 hours of studio time at a cost of £1,750, a price that included the sleeve artwork. It was released on January 12, 1969. It’s a record that has become so familiar that it’s now impossible to imagine the raw impact of its arrival.

It is a landmark recording, and yet reaction to its release was equivocal. Rolling Stone’s review of the record began a rift between magazine and band that lasted for some years. Written by John Mendelsohn, it claimed that Led Zeppelin had stolen some of their ideas, citing specifically Black Mountain Side as an uncredited reworking of Bert Jansch’s Black Water Side, and Your Time Is Gonna Come as a lift from Traffic’s Dear Mr Fantasy. The band had also recorded their version of Willie Dixon’s I Can’t Quit You Baby, a song also covered by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers on their 1967 album Crusade, and You Shook Me, which was written by Willie Dixon and JB Lenoir.

Led Zeppelin I closed with a song called How Many More Times, an old tune that Robert Plant had sometimes used in his previous group Band of Joy, incorporating some lyrics and riffs from Albert King’s The Hunter.

Some of these songs would become the subject of scrutiny. Page happily admitted that he had been a big fan of Bert Jansch, and that he’d utilised some of the guitarist’s tunings and finger picking techniques. And yet the song itself was based an old folk number composed by Anne Bredon in the 1950s.

However, it was You Shook Me, the Dixon-Lenoir tune, that brought the most controversy with it. Jeff Beck had covered the song just a few months before Zeppelin, and had released it on his album Truth. He accused them of stealing his idea. Page maintained, with some substance, that it was a merely a coincidence. Both had played the song in the Yardbirds.

The row was to cause a rift between Beck and Page that lasted a while, an irony considering Page had contributed to Beck’s Bolero, one of the best loved tunes on the Truth album. Willie Dixon had a greater argument that he’d been wronged, as he didn’t receive a songwriting credit on the album, a situation he remedied through the courts.

Led Zeppelin II, which came out within a year of Zeppelin’s formation (they also toured four times during those 12 months), featured more songs that had links with older tunes. The record opened with Whole Lotta Love, one of rock’s landmark moments, and one that owed a debt to Willie Dixon’s Woman You Need Love. Dixon’s song had previously been covered by Muddy Waters, and Zeppelin’s version was lyrically and musically more similar to the Waters’ version.

Another of Dixon’s compositions, Bring It On Back, was the reference point for Bring It On Home, whilst Sonny Boy Williamson’s cover of Dixon’s original song was very deliberately used by Zeppelin as an intro and an outro. Once again Dixon was not credited. Arc Music, the publishing arm of Chess Records, sued and won, and yet Dixon did not receive payment until he sued Arc some years later.

Later pressings of Led Zeppelin II credit Dixon. There were remakes and reworkings on Led Zeppelin III too. Gallows Pole, for example, was a new take on Leadbelly’s Gallis Pole. Tellingly, Leadbelly’s song was itself a version of an old folk song The Prickle Holly Bush. In borrowing from the past, Zeppelin were part of a long and glorious tradition of folk and blues players – not modern day pirates.

With Led Zeppelin IV, released in 1971, Zeppelin became the biggest band in the world. Their music had evolved, in two years, from electric blues to something regarded as deeper, broader, more esoteric and challenging.

They were a band that could record Rock And Roll and Stairway To Heaven, Misty Mountain Hop and The Battle Of Evermore. They were stretching a long way beyond any influence they had ever acknowledged or even considered.

When The Levee Breaks, the album’s closing song, was ushered in by one of the most famous sounds in rock’n’roll, John Bonham’s drums recorded in an echoing stairwell in a Hampshire mansion called Headley Grange. That drum sound ripped the song far from its origins as a Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie composition from 1929, and in the same tradition, Bonham’s drums were to become one of the most sampled and copied noises in rock history.

The band’s subsequent music took them further from their roots. By the time they released Physical Graffiti, they themselves had become hard rock’s shaping element. Just two songs from the double-album set directly referenced those early influences: Custard Pie was a partial raid on Bukka White’s Shake ’Em On Down, while In My Time Of Dying was an old spiritual song that had once been revived by Bob Dylan for his eponymous first album.

And Led Zeppelin’s final record, Presence, included Nobody’s Fault But Mine, a song first recorded by Blind Willie Johnson in the 1920s. After the Willie Dixon lawsuits, it occasionally became fashionable to snipe at Page and Plant. But those jibes were mediated by the development of the contemporary music industry. Conventions of publishing and plagiarism had become established, and they were only retrospectively applied to bands like Led Zeppelin and Cream.

It became easy to paint them as exploiters of the artists that had influenced them, rather than what they were: young men seized by the momentum of their era, young men thrilled to be extending a tradition that they both loved and revered.

What such arguments also ignored was the sizeable influence that Led Zeppelin extended outwards. By taking elements of the music that formed them and reshaping it, they in turn became the blueprint for thousands of other bands and songs.

John Bonham’s drums might be the single most sampled sound in music. Jimmy Page’s riff for Kashmir has been restyled innumerable times. Furthermore, Robert Plant’s vocal technique offered something to every singer from Rob Halford to Jeff Buckley.

There must now be more Led Zeppelin cover bands than any other post-60s rock group can boast – not to mention a host of pale imitators. The real band – sometimes to their chagrin – have been credited with the whole invention of the hard rock/heavy metal genre itself.

That might have dented their reputation amongst the most sober of musicologists, but the sheer, abandoned thrill of listening to Led Zeppelin’s music will continue to place them in a position below only the Beatles and The Rolling Stones in terms of formative influences. Whatever they took, they repaid many, many times over.