How Mike Oldfield made Crises and ended up with a Top Five hit single!

Mike Oldfield's eighth studio album, 1983's Crises, saw him riding a wave of new popularity in the 80s

According to Richard Branson, Virgin were looked on as a hippie label that was not really serious, and I was their one hit artist,” says Mike Oldfield assessing his and the record label’s situation back in 1977. “So they were feeling a little foolish, I suppose, and this is why they signed the punk acts and switched all their attention onto them. At the time Richard was quite a close friend, he was my manager as well, but I felt a little brushed under the carpet.”

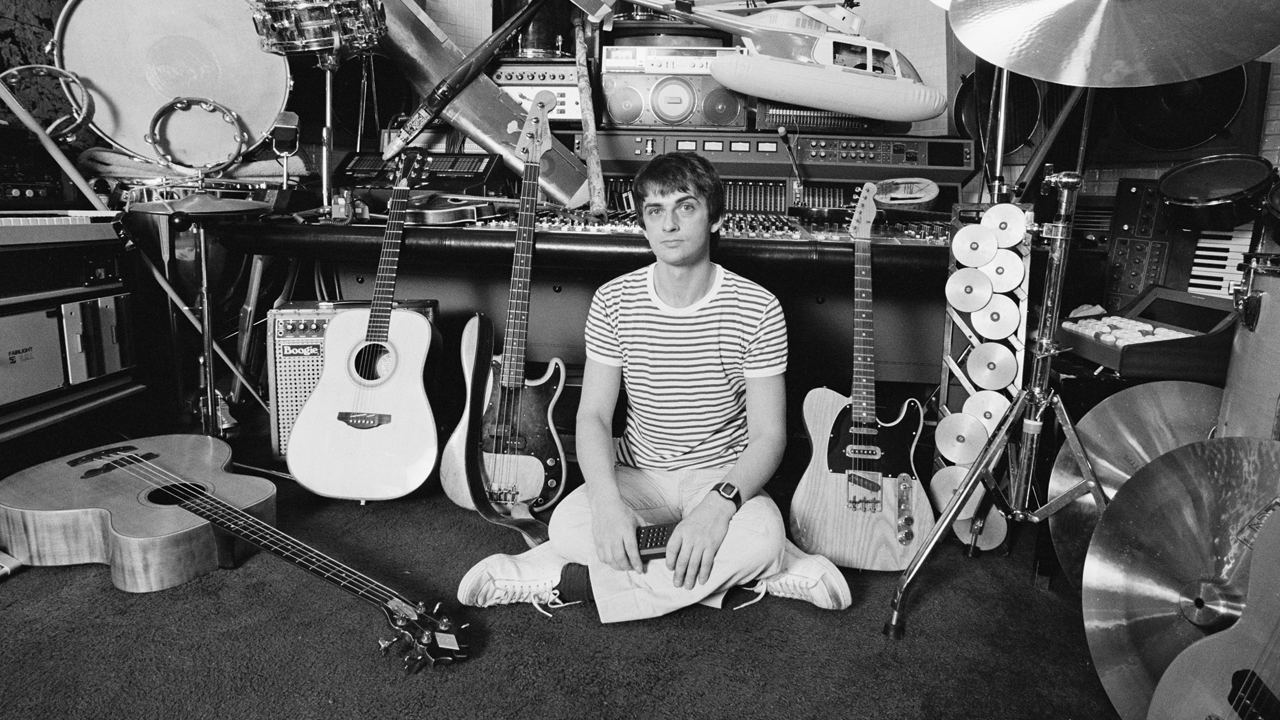

To many progressive rock musicians, the 1970s was a decade that they had made their own. And few had done so as spectacularly as Mike Oldfield. With his 1973 debut Tubular Bells he had expanded musical possibilities for good, demonstrating that if a musician had the instrumental facility, they could, through overdubbing and more than a little inspiration, produce large-scale pieces almost entirely solo.

In this case, one that sold vast amounts worldwide and had almost single-handedly kept the record company afloat.

But whereas Tubular Bells had been something fresh, new and perfectly tuned to the zeitgeist, four years down the line, progressive rock had done what no other popular musical movement had managed – it had provoked an enormous backlash, and was under fire from punk rock and some sections of the music press. This all coincided with Oldfield reaching something of a creative impasse, as he explains.

“Tubular Bells was fantastically successful and then the next album Hergest Ridge (1974) was very successful – but on the back of Tubular Bells and got critically attacked. Ommadawn (1975) was very well received critically and that sold pretty well, and then I had this Incantations album [1978], which took me three years and my heart wasn’t really in it, to be honest.”

Oldfield was faced with both creative frustration and an industry in a state of flux. “In a way I had to reinvent myself,” he admits. He participated in Exegesis [a form of alternative therapy involving rebirthing], travelled to New York to record and embarked on a number of tours. He was, he says: “tossing the chips in the air to see where they would land.”

This new tack didn’t yield instant results. With subsequent albums Platinum and QE2 featuring some less than convincing songs, cover versions of music by the likes of Gershwin and Abba, and ill-advised, jocular excursions like the punk-folk instrumental Punkadiddle, Oldfield was in danger of heading into a creative cul-de-sac. But with Five Miles Out [1982] he balanced a 25-minute, largely instrumental composition Taurus II, with shorter pieces, of which Family Man signalled an improvement in his songwriting. He further refined this approach on Crises [1983]. Not only was it artistically his best album since Ommadawn, it charted at Number Six (the highest position since that album’s number four) and also yielded an international hit single with Moonlight Shadow.

“Suddenly I was popular with the record company again, with people going: ‘Mike, Mike, hello! Where have you been?’,” recalls Oldfield, clearly amused at the memory. With another side-long instrumental title track and a group of shorter songs, Crises kept his original fans on board, while appealing to a pop audience. But was he ever worried that in taking this approach he might fall between two stools?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“No, no, no, no, I never think I’d better do something because of this or because of that,” he counters vigorously. “It just felt like the right thing to do at the time. I don’t really make plans for things. I first started out making music in folk clubs, when I was about 11 or 12. I used to write these little songs, they weren’t very good at all, but then I would make long instrumentals on steel–stringed acoustic guitar. So I have always had these two aspects: short songs and long instrumentals.”

The title track weighs in at just a smudge over 20 minutes and is in a number of sections. Did he have an idea of an overall structure in his mind when he began composing it, or did he gradually piece it together?

“There’s usually a long period of coming up with little bits and then seeing how I could fit them together, with musical motifs that crop up throughout the piece, or a theme that links it all,” he explains. “I also throw out a lot of ideas that don’t even get to the drawing board.

“If I sit down and try and write something, it doesn’t usually work out very well. But there are times when out of the blue a little tune or motif or harmonic progression will appear in my brain, and I’ll go: ‘Ah, thanks!’ I’ve likened it to receiving a cosmic email from someone, or some force. I suppose that’s called inspiration, but I’ve never really got to the bottom of it. I’ve learned now not to question it, just to follow it if I get it.”

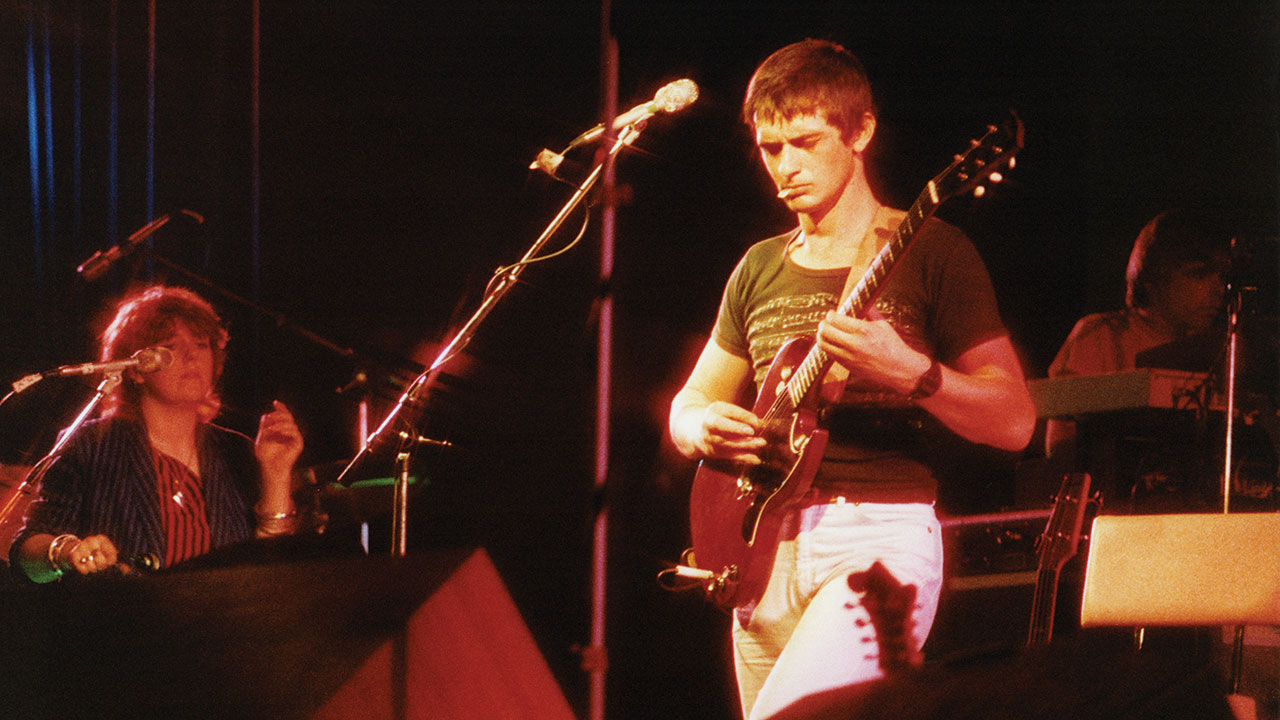

A new name appeared on the credits for the first time alongside Oldfield, the prodigiously talented drummer Simon Phillips, who was originally drafted in as a session player, but who ended up with credits as assistant producer. Although he was new to working in the control room, he learned quickly and did a lot of the engineering when Oldfield overdubbed guitars or keyboards.

Although Phillips wasn’t involved compositionally, he did make his mark musically, particularly on the title track Crises which feels sleeker, its constituent parts more integrated than the similarly lengthy Taurus II on Five Miles Out. His drumming helps to knit the elements together, especially when playing his near-melodic tom-tom patterns with Oldfield’s sequencers.

Oldfield was not blessed with much of a voice, but on the title track Crises, his brief snatches of singing are urgent and effective, most notably on the ‘Watcher in the tower’ section. “Funnily enough, when I was remixing it I was dreading that, as I thought: ‘Oh God, I’ve got to listen to my voice.’ But it wasn’t that bad actually, it sounds alright,” he concedes.

But if some of his previous songs had come across as a tad self-effacing, a bit like makeweights, the songs on Crises sound more fully realised and far more confident – particularly the single Moonlight Shadow which reached number four in the UK and Number One in many European countries.

Oldfield mulls over this idea, and after a long pause, exhales loudly. “They ended up like that, but they didn’t start off like that,” he explains. “For example, Moonlight Shadow. I got the musicians together, scribbled out some chords and said: ‘Here you go, boys, let’s play this’, and bashed out this backing track that sounded marvellous straight off. And I thought: ‘What is it? Is it an instrumental? Is it a song? What should I do with it?’ Something in me thought that I would make a great song, but then I had to think of lyrics and think of a singer.

Oldfield invited Hazel O’Connor to bring her own lyrics and have a go at singing it, but it wasn’t quite what he wanted. He thought about what to do with the track for months, then booked Maggie Reilly – who had sung on Family Man on Five Miles Out for a session, forcing himself to come up with some lyrics.

“I sat down all night with a lovely bottle of Chateau Latour, a rhyming dictionary and thesaurus, and a pen and pad,” he recalls. “The first thing that came into my mind was that it was night, was that there had to be ‘moon’ in it. The moon was making shadows of the trees and I thought: ‘Alright I‘ll have some of that in’. Ideas and phrases and words poured out in a great big mixture onto the pad, and I started fitting them together. At about five o’clock in the morning I had something that looked like a reasonable song.”

“Maggie turned up next day and she wanted to sing it out in a soulful way, belt it out as rock song. And I thought that wasn’t going to work, so I put the mic up very close to her mouth and said: ‘Maggie, just whisper it, like you’re whispering in someone’s ear,’ which she’d never done before.”

Later, when Oldfield was putting on his guitar solos, he and Phillips agreed that there should be two solos: one clean and one that should sound “almost like a saxophone”. Then, after an all-night mixing session the song was finally complete. “I’m pleased with all the work that went into it,” says Oldfield, “because it was successful and it still sounds very good today.”

Reilly also sings on the seductive, cyclical melody of Foreign Affair, again with a light touch. The one instrumental on the second side is the concise but flamboyant acoustic guitar-based instrumental, Taurus 3. Jon Anderson helped create another highlight with In High Places. Having left Yes and already achieving success with Vangelis, he was looking around for other musicians to collaborate with and got in touch with Oldfield. The song was put together in a completely different way to Moonlight Shadow.

“I remember it was just around the time I was doing The Killing Fields soundtrack. It was at his house in Kensington and Vangelis was there. Vangelis had just done Chariots Of Fire with David Puttnam, who was now working on The Killing Fields, so I was able to pick his brains about technical things in film music, like synching up.

“I had another bit of backing track which I thought could make a song and Jon took it off on a cassette and wrote some lyrics. Simon and I flew off to Paris in the morning to record – Jon was a tax exile at the time – and flew back late at night.”

The other outstanding vocal performance is by Roger Chapman, formerly of Family, and by then leading The Shortlist. Oldfield had a backing track recorded at around the same time as Moonlight Shadow, but this time he had a far more concrete idea of what to do with it. He had been reading in the newspapers about the subjugation of the Polish trade union Solidarity, and the imprisonment of the union activist, Lech Walesa. He’d travelled a lot in Germany and the rest of Europe and had experienced the stark contrast between the Iron Curtain countries and the West, all of which inspired the song, Shadow On The Wall.

Then Oldfield thought of Chapman. He had auditioned for Family after leaving Kevin Ayers in 1971, but although he didn’t get the job he remembers some encouraging words and “good vibes” from the singer.

“He belted it out in about one take and it made your hair stand up,” Oldfield says. “And it became a sort of anthem in the Eastern Bloc before Glasnost, before the wall came down, which is great.” Such a performance seemed to galvanise Oldfield’s guitar playing, which sounds tougher and grittier than usual. “Well, it had to be for that song,” he agrees, adding, “but then I always go for it.

Crises found Oldfield sharpening his artistic focus and effectively setting himself up for the second phase of his career by re-establishing himself as a composer of large scale, intricately structured instrumental suites, while taking his songwriting onto another level and into the charts. He was firmly back into the spotlight. The Crises tour for the album saw him headlining Wembley Arena in July 1983 (a recording of the show is included in the album’s 30th anniversary deluxe edition), but it wasn’t quite all plain sailing from there.

“There’s nothing that makes you more popular with your record company than having a hit,“ Oldfield reflects. “Richard came to me and was so happy. He said that I should do more albums of songs like that. As a result I came up with a couple of albums that I wouldn’t have done otherwise, that were all songs – Discovery and Islands. They aren’t really my best work, although there is the occasional good idea on them – but that was a result of Crises and the success of Moonlight Shadow. But then came Amarok (1990), one hour of only hand-played instruments, a crazy, mad, wonderful thing. I had swung right back to my first love in music – the long instrumental.”

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.