This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 63, published in February 2004.

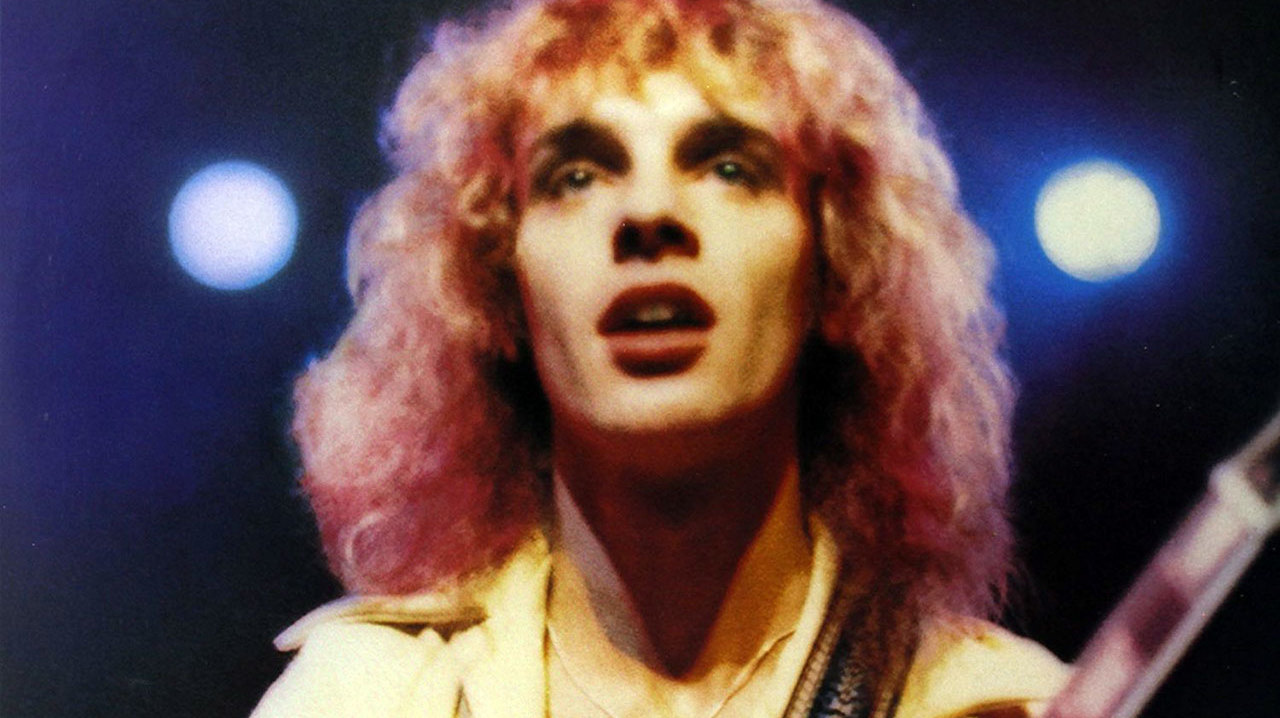

At 53 years old, the man who was the Face Of ’68 during his fledgling days as a member of The Herd has aged gracefully in his transformation into the Survivor Of ’04. Whatever else he did or will do, his name will be forever associated most with the global phenomenon that was Frampton Comes Alive, originally a double-live vinyl album that achieved sales of around 16 million copies worldwide. And which is back now in shiny, new SACD and DVD-A editions.

The massive success of Frampton Comes Alive overshadows many other aspects of Peter Frampton’s amazing 36-year career. They include: teenage protégé and pin-up in his Herd days; arena rocker as guitarist/vocalist with Humble Pie; soccer team co-owner; Sergeant Pepper movie band leader; guitarist for mates such as George Harrison, David Bowie and Ringo Starr; star of both small and silver screens, from The Simpsons to Almost Famous. And then there are the brandy-fuelled binge-fests that alcohol-clouded his most famous years…

But before we even start to recount those tales, let’s paint Frampton’s current picture in the rosy hue it deserves. The admirable new, self-produced album (for his own Framptone label, via SPV) Now led to a return to England last November to guest with his old mate Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings at the Royal Albert Hall. There’s now the imminent promise of another London show on February 20, at Shepherd’s Bush Empire, as part of a European tour. “I couldn’t be happier with where I am right now,” Frampton says. “It’s been a slow, long rebuilding process, but I’m very happy.”

And so he should be. He might now resemble what you might expect his own granddad to look like, with the specs, goatee and shiny pate, and almost unrecognisable from the bubble-haired idol of 1976, but when I saw Frampton and his band play the Town Hall Theatre in New York the night before our chat, new songs from Now sat pretty among the obligatory and still vital ‘signature’ songs Show Me The Way and Baby I Love Your Way.

“I think there’s some on there [the new album] that are going to be with us a long time,” Frampton says. “On some of the last records, they come and they go, but when you’re dealing with an audience in Missouri they’re expecting Frampton Comes Alive, and you do Hour Of Need or Not Forgotten and they go down as well as Lines On My Face. It’s pretty amazing. This band [including ‘…Comes Alive’ band member Bob Mayo on keyboards] is phenomenal. We’ve been together so long, and we’re a big four-piece. Hats off to the guys.

“This time, with spending two years on and off in the studio making the new CD, having the ultimate control by being able to mix it in my basement and doing over twice the amount of material, I picked the songs that really felt like an act on their own, and could be just that. Honestly, you could literally do that whole album [live], there’s enough light and shade in it.”

Peter Frampton spent a decade building up to one of the biggest-selling live albums ever released, and then spent the next 25 years explaining to people where he went. His incredible year of 1976 was followed by a fair-to-miserable time in the remainder of the decade, thanks to a mixture of bad luck, bad judgement and quite a bit too much booze. But overriding all those elements has always been his unadulterated love affair with the guitar, for which he blames one Hank B Marvin.

“The first Shadows album,” he breathes, still in awe. “I can still play the whole record. I’m sure if Mark Knopfler and Pete Townshend and Jeff Beck were in the room, we could all play it all the way through, it’s so indelible. Mark to this day says if he plays a Stratocaster, it has to be red. “The biggest moment in my life, apart from playing on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, was what, seven years ago, playing Shepherd’s Bush. We’ve got an English road manager who’s a Shadows nut.

"He called me and said, ‘Pete, are you sitting down?’ I said, ‘I will be’. He said, ‘You’ll never guess who just called for tickets – Hank Marvin!’ I’d met Hank a couple of times, we knew each other well enough to say hello. The show was great, packed, a lively welcome home. Afterward, backstage, my parents went up to him straight away and said, ‘Peter’s going to be so excited’. They monopolised him.

"Anyway, we went into a private room and he asked me what strings I used! It was a wonderful moment.” (At the New York show, Frampton even played a bit of The Shadows’ 1961 instrumental chart-topper Kon-Tiki.)

Born in Beckenham in Kent in 1950, Frampton got his first guitar at the age of eight, but that wasn’t his first string-driven thing. “I was up in the attic when I was about seven, helping my dad down with the suitcases for the summer holiday, and I said: ‘Dad, what’s this?’” he recalls. “It was this little case with my grandmother’s ukulele. Next year, doing the same thing, I said: ‘Can you play it, dad?’ ‘Oh yeah,’ he responded. So he did Tom Dooley or Freight Train or something. That Christmas I said: ‘Can I have the other two strings now’?’

“I saw this Fender Stratocaster and this weird-looking Gretsch hybrid guitar with a bar on it. I heard this sound, and I just liked anybody that had a guitar. I didn’t care what they were singing about, it was the sound of an electric guitar.”

The clock moves on to Christmas Eve 1958. “My dad bought two guitars. He bought a classical six-string for himself, because he played in a college dance band before the war, and he got me a steel-string – they were called Plectrum guitars, no make, I don’t know what it was.

“My brother still believed in Father Christmas, so my dad put the guitar at the bottom of my bed in the middle of the night. I woke him up at 3.30 in the morning and said: ‘How d’you tune the bottom two strings?’ He said: ‘You bastard, go back to sleep’. But he tuned it up for me. That was it, I didn’t go to sleep.”

Frampton’s first ‘gig’ was at the age of eight, as a Boy Scout playing Cliff Richard and Adam Faith hits of the day at a variety show. “Then of course Apache comes out [by The Shadows, in 1960], so that was it. We got our first Dansette record player. My dad brought it home on the back of a Lambretta; we didn’t have a car yet. For Christmas I got The Shadows’ first album, and Django Reinhardt’s Hot Club de France with Stephane Grappelli which I thought was horrible! That’s what my mum and dad partied to in the 30s and 40s.”

As the British beat boom grew ever louder, Frampton soon realised that he wanted to travel his own route. “I took a detour,” he says. “Before The Bluesbreakers, when Eric Clapton was an underground legend, you’d see the slogan ‘Eric Is God’ on the overpasses all over London. I noticed that everybody was reading The Beano [as Clapton was on the cover John Mayall’s 1966 album Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton] wearing sneakers and playing Hideaway. I was still at school, and lucky enough to be asked to be in this band called The Preachers, which had the original drummer of The Rolling Stones, Tony Chapman, who was Bill Wyman’s best friend.

“Tony had actually been right before Charlie [Watts], and had introduced Bill to the band. So Bill felt a great deal of gratitude and he said to Tony: ‘Get a band together and I’ll produce it for you’. Which he did. I was like the little upstart fourteen-year-old guitar player; I didn’t sing.

“Tony had seen me in another band. I worked in the local music shop, polishing guitars on Saturdays, restringing them, so I was always jamming in the shop with all these professional musicians, and word got around. He called me up and said: ‘Here’s this stack of records’. It was everything from Otis Redding’s Otis Blue to Wes Montgomery, Mose Allison, Roland Kirk, Kenny Burrell, Joe Pass… every jazz guitarist, and R&B and blues, Muddy Waters… so diverse. It was Saturday. He said: ‘Tuesday night. Get this down, learn this.’ I said: ‘Thanks a lot’.

“So coming from the Hank Marvin melodic sense, I found initially that jazz was more melodic to me than blues. I loved both. But that’s when I decided there’s a million Eric Clapton wannabes out there, and even though I love it and it’s very seductive I’m going to go a little different here. So I made a conscious effort to go the jazz route.”

Frampton was at Bromley Technical College, where a certain David Jones, later David Bowie, was a fellow student and friend. “David was at the school before me, but I knew of him because he was in a local band already. My father was his art teacher for three years and they’ve stayed in touch. David and I brought guitars to school, and at lunchtime we went to the art department and hung out on the stairs, where there was a great echo, and played Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran songs.”

Soon Frampton, a whiz-kid of just 16, joined the mod-pop group The Herd, formed before his arrival and signed to Fontana. But Frampton remembers that their accession to the charts in 1967 (with ‘From The Underworld’, the first of three hits) sent them in the wrong direction down a one-way street.

“When we had our residency at the Marquee Club we had a section every Saturday for that whole summer where we’d do our jazz for fifteen minutes, right in the middle of the act. I would become Grant Green, Andy Bown – sorry, Andrew Bown [later of Status Quo] – would become Jimmy Smith or Jack McDuff, and Andrew Steele would become Grady Tate. We would do a couple of Smith and McDuff numbers, then I’d do a blues instrumental, Blues In G, and it used to bring the house down.

“Of course, only the people who knew us before ‘From The Underworld’ knew us as that sort of musical band. Then The Herd went through their big pop success. [Their managers, Ken] Howard and [Alan] Blaikley came along and said to me: ‘You’ll sing’. I said: ‘Excuse me, I don’t sing, I do Hide Nor Hair by Ray Charles and one other number; Andy and Gary [Taylor] are the singers, I’m just the guitar player’. They said: ‘No, you’ll sing.’

“That was beginning of the end for the band. [Journalist] Penny Valentine did the piece and the editor put ‘Face Of ’68’ on it and it was all very exciting, but I realised then – and I was to realise later – that teenybopperdom is the death of musicians, basically. It’s very quickly over.”

But surely getting that sort of adulation as a teenager must have been seductive?

Frampton nods. “Oh, of course, it’s very hard not to go: ‘Ooh, that’s me’,” he says. “But after about three weeks of being screamed at you realise: ‘I can’t hear what I’m playing, and they don’t really care if I’m playing or not’.

“Being that I was the new guy, really, and all of a sudden got pushed to the front, it created a very bad vibe. And after our third hit, I Don’t Want Our Loving To Die, we realised we’d been screwed by someone in the organisation. We didn’t know who, so we got rid of everybody to try and find out who it was.”

It was shortly afterwards that a slightly discouraged Frampton met some of his heroes, one of whom would be writ large in his career for years to come: “I bumped into Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane [of The Small Faces]. They called up and said: ‘We’ve heard you’ve got some problems, and we’ve been through it, would you like to come down and have a chat?’ Which was very nice of them.”

Marriott had been royally ripped off. “‘Don’t get talked into situations that you’ll regret later. That’s what to avoid,’ Steve told me in 1989,” Frampton remembers. “‘That’s turned many a good musician into a bad introvert,’ Steve used to add.”

Two years later, when he had been reunited with Frampton to work on new material, news came of Marriott’s tragic death in a fire at his home.

“We developed this instant rapport,” Frampton says of his friend and one-time colleague in Humble Pie. “I wanted to be in The Small Faces, especially after the Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake album [1968]. Steve said: ‘You should leave that band [The Herd] and form your own, they’re too pop’. And I said: ‘I know’. He was just the greatest teacher I could ever have. I can’t say enough good things about Steve.

“Humble Pie was formed after a Johnny Hallyday session. Glyn Johns had asked me to play. He said: ‘I’m producing this record by Hallyday in Paris and he wants The Small Faces to be the backing band, but we need another guitarist.’ It was my dream come true. I joined The Small Faces for a week.

“When I got back from that session, Steve called me at Glyn’s house. We were listening to Led Zeppelin I – it was before it came out, and Glyn wanted to play me this new band. The phone rings, and it’s Steve. ‘’Ere,’ he says, ‘I fucking walked out. I walked off stage at Alexandra Palace. I’m fed up, I’ve left the band. Can I join your band?’ I said: ‘Er, yes’. So that was it.”

Marriott, who had already found drummer Jerry Shirley for Frampton, now brought bass player Greg Ridley from Spooky Tooth, and Humble Pie was born.

“The following day I got a call from Ronnie. He came round to this hovel of an apartment that I had in Hammersmith – basement, no light – and he asked me to join The Small Faces. I said: ‘You’re a little late’.

“Humble Pie was the best band you could ever be in, as far as I was concerned, because you’ve got my idol there. Steve would open his mouth and gold would come out.

It was during the Humble Pie years that Frampton really honed his reputation as one of the most accomplished guitarists of what could be termed the ‘album-rock era’.

“It was great, because even though I now liked singing, I didn’t need to be the front guy, there was no need at all. You had this diminutive figure and this black man’s voice that came out at 300 watts; Steve didn’t need a microphone. But he was very gracious and a great teacher.

“That’s when I really got into the blues. I’ve never been someone who wanted to play a thousand notes a minute, it’s always the choice of the right notes. And of course we’d do Muddy Waters numbers and a lot of different blues things. Now I could do that, because Steve would play the dirt and I’d come over the top.

“Stone Cold Fever [originally on Pie’s 1971 album Rock On] is the definitive point of what everyone in Humble Pie did best. It was my riff – very Zeppelin-influenced, obviously. Steve wrote the melody, which was pure R&B, over this heavy rock riff. Then for the solo we went into our version of jazz. That’s the peak for me of when we were all enjoying ourselves to the utmost.”

Earlier, a surprise UK No.4 hit single for Humble Pie with Natural Born Bugie in the summer of ’69 had not been in the band’s masterplan.

“Guess what?” Frampton asks. “We started to get screamed at again,” he says, remembering how Humble Pie had shunned mainstream publicity. Marriott, ever rock’s artful dodger, deliberately incurred Tony Blackburn’s disapproval by calling him ‘David’ on Top Of The Pops.

“Harry Goodwin, the photographer, said: ‘Come on, Pete, bring the lads, we need to do a photo’. So we walk in the room and there’s a pie, four plates and four knives and four forks. Now you know where the pie ended up. It ended up on the wall. We never had our picture taken.”

The band decamped to America and gigged their balls off. “No one knew about us, it was just come over and play for the biggest amount of people in the shortest space of time as we could and build a following,” Frampton explains. “The beauty of Humble Pie was that we were able to do whatever we wanted. And America really defined our direction. The band was very equal in its input. Steve was the leader in the end because of the amount of talent he had.

“People have said it got too heavy for me, and that’s absolutely not true; it got to the point where I needed to do my own thing. I wanted to go back and do some more acoustic stuff as well as the blues and heavy rock. We were just about to have our first [US] hit record as I left – I was part of the Rockin’ The Fillmore live album. A big part in mixing it with Eddie Kramer. “

As [manager] Dee Anthony came over and showed me the cover, I said: ‘I’d like to meet with you alone if you don’t mind, because I’m going to leave the band’. He said: ‘You’re crazy’. And Steve got very upset. They all did. And I was tearful about it. It was a very hard decision to make.

“In the end, when I did leave and had my first record out, I opened for Humble Pie in England and they stood on the side of the stage and blew raspberries. Then things developed. And it would never happen now, but five albums later…”

After two years with Humble Pie, Frampton left in 1971 and signed a solo deal with A&M. His solo career simmered on a low heat for years before coming to the boil, in a way that today’s impatient music industry would never have waited for.

Before any solo recording he played on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and Peter’s memories of George form a connection to his current Now album, which includes a fitting cover of While My Guitar Gently Weeps. Years later, early in January 2002, Frampton and his band took part in a Cincinnati show about the city’s musical heritage. “We’d lost George at the end of November. He was a friend, I played on All Things… and another production of his, by Doris Troy, and I thought: ‘Get the band to listen to it and we’ll try it as the last number’.

“When we finished there was that silence, and then people went nuts, and it blew us all way. The band came off and said: ‘We know you don’t like doing covers, Pete, but we’d really love to try it and do a tribute on record’.”

After All Things Must Pass, Frampton returned to the freeway, this time at the wheel of the newly named Frampton’s Camel. “It was a carbon copy of what Humble Pie did,” he says. “It was the old-school thing of start in the clubs, fill the clubs. Go to the theatres, fill the theatres. Play with other people. Doesn’t matter what it is. If they can fill the building, open for them. So we did open for Black Sabbath and ELP. Everyone you would think Humble Pie shouldn’t open for, we opened for. And that counts for me, too. I’m opening for ZZ Top one day.”

By the middle of the decade, and hundreds of shows later, the legend of Frampton Comes Alive was born.

“The ‘Frampton’ album sold more than all my four previous records put together in the States – three hundred thousand copies. I said: ‘Why don’t we do what we did with Humble Pie, do a live record?’ So we set about doing a single live record, because even though we’d had some sort of success with ‘Frampton’ we felt let’s not push our luck.

“So we set about doing three concerts: two shows in one night at Marin County Civic Center [San Raphael, California], and then two nights later at Winterland in San Francisco – it was the seventeenth of June 1975, I can see the tape box! It was good because we owned the airwaves in San Francisco; after the Frampton record I could do no wrong there, and this was my first time headlining.

“Well, as soon as we walked on the stage there’s like 7,500 people out there and I was like: ‘Oh my God!’ And I think it gave us such a kick up the arse. We did this show that was one where you walk off and go: ‘Oh, wish we’d recorded that’. The only difference being that we actually did. So it was just very special.”

When A&M supremo Jerry Moss heard the single album at Electric Lady studios in New York he immediately upgraded the project to a double album. His instincts, and Frampton’s, were spot-on. “It was just the apparent energy that came off the tape,” Frampton says. “So we knew we had something. We thought, three hundred thousand for Frampton? This might be a gold record – half a million! And of course it virtually did that in the first two weeks. Within six weeks, I think, it was number one, and it went one-two, one-two all summer. It was unbelievable.”

Released in 1976, Frampton Comes Alive spent 97 weeks on the US Billboard chart, 10 of them at No.1, flip-flopping at the top with Wings At The Speed Of Sound. When …Comes Alive was last certified in the US, in 1984, it had sold six million. Today the figure would be far higher.

In Britain the album hit No.6 in a 39-week chart stay. Worldwide it yielded the huge hits Show Me The Way (starring the famous, pioneering ‘taking guitar’ voice box) and Baby I Love Your Way. In September Frampton was invited to the White House by US President Ford. The Face Of ’68 was now the Bank Balance Of ’76. But alarm bells were soon ringing.

“I had these awful stomach cramps about some of the things we were doing media-wise – the photo with the shirt off, the poofter hair. I was thinking, okay, this is really big here now, I need some help. And they went by the old rules of trying to hype something that really didn’t need hyping.

“It was a self-motivating machine, and before the onslaught of front covers and the pretty-boy image came out. People were buying that record for its musical content, and the fact it was a great band recorded live, doing basically a best-of Peter Frampton’s material over the last five years and one Humble Pie song.

“It’s very easy in hindsight to see this now, but instead of pulling back and getting [rid of] the satins and putting a pair of jeans on, and maybe growing a beard like I was still in Humble Pie, I let it happen. When you’ve been striving for fifteen years to have something like this happen, again it’s very seductive, isn’t it? It’s very hard to say no.

“As Cameron Crowe puts it, and I’ll paraphrase, I was strapped to the nose-cone of a rocket and I went through the ceiling of the atmosphere, and there was nobody else up there except me. And that’s the person who should have made the decisions. I’d been playing these numbers for years now already; I wanted to take two years off, like The Eagles.”

Drugs didn’t really threaten Frampton’s livelihood. But drink did, as he even made plain in the tongue-in-cheek opening lyric of the album’s US rock radio anthem Do You Feel Like We Do: ‘Woke up this morning with a wine glass in my hand… whose wine? What wine? Where the hell did I dine?’

“I was a late bloomer,” Frampton says. “I’d tried smoking pot but it didn’t do anything for me. Then during the early 70s there were other things out there. The coke thing happened – it was just everywhere. We thought we were so great when we were doing that stuff. Then you go and do a session like that, come in and listen to it the next day and it’s garbage.

“I never went any further than that. But my real problem was drinking. I was never an everyday drinker, but I was a binger. There’d be those nights every now and again where – what is it they say? – one’s too many and a thousand’s not enough. I’m just approaching a year; I just stopped everything. I hadn’t really drunk that much over the last ten years, but there was always that fear that one night I’ll finish the bottle. Or two. I’m just a chocaholic now.”

It’s easily forgotten that, far from fading, Frampton stayed ‘alive’ in 1977 with a follow-up studio album, I’m In You, that sold over a million and reached No.2 in America. But there was no upstaging the live monster.

He became a soccer team co-owner, backing the Philadelphia Furies with Paul Simon and Rick Wakeman. But 1978 was to become a real annus horribilis, involving a serious car crash and the taking the major role of Billy Shears in the golden-turkey Hollywood film adaptation of The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Frampton’s best US chart showing since then was No.80 for the Premonition album in 1986. But the following year brought some rewarding recognition when old mate David Bowie invited him to play lead guitar on the Never Let Me Down album and the accompanying tour.

“The Glass Spider tour was like joining the circus,” Frampton laughs. “It was a fantastic experience, and most certainly the biggest tour I’ve ever done, in every way. I thank David for taking me, because it was a great reintroduction worldwide, post- …Comes Alive hoopla, to me the ‘guitarist’. What’s not to love? I got to play all my favourite Bowie songs and he sang them!”

The charts since have brought recurring good news, with covers of Baby I Love Your Way becoming huge hits for Will To Power in 1988 and Big Mountain in 1994. By 1997 Frampton was playing his hits as one of the featured artists in Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band.

“I’d started up again in ’92, and I realised that whether I could sell another record or not I wanted to play. I got the band together and said: ‘I missed playing so much. Let’s just do six weeks of clubs’. By the end it wasn’t six weeks, it was six months. And we ended up playing at Pine Knob in Detroit in front of 15,000 people again.”

In 1993, Frampton and his family his family moved from Los Angeles to Nashville, and then a couple of years ago to Cincinnati, his wife Tina’s home. “Basically I love it. I go to Starbucks, I know everybody there. It’s a small city.”

On the technical side of things, Frampton has an accessories company for guitarists, Framptone, started with partners Mark Snyder and John Regan, which supplies the celebrated talkbox as well as the Framptone Amp Switcher. Users already include Dave Grohl and Richie Sambora. “Framptone came from necessity, because there was not an amp switcher out there that did what I needed,” he says.

But as all fans of a certain animated series will avow, it’s not Frampton Comes Alive that makes him immortal, nor even his role in 2000 as ‘Reg’ in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous. It’s his appearance in The Simpsons. In 1996 he appeared in Homerpalooza, a spoof of the rock festival circuit, and the grunge scene in particular, co-starring Cypress Hill, Sonic Youth and Smashing Pumpkins.

“It was such an honour, because the ‘biggies’ do that one,” Frampton says. “They were so great to work with. I did it in fifty minutes, and they let me ad lib. They said: ‘Just say something as you’re walking past Homer’. So I said: ‘Twenty five years I’ve been in this business, I’ve never seen anything like it’. And they animated my ad lib!”

As we finish our conversation, I inform Frampton that The Shadows are reforming for a farewell tour later in 2004, and suddenly he’s like that excited ten-year-old Hank Marvin fan again.

“I’ve had an incredible career,” he says, summing up. “No, I didn’t stay up there as the biggest act in the world, and yes I’ve had some sad times, but the beauty is I’m still doing what I love to do.”