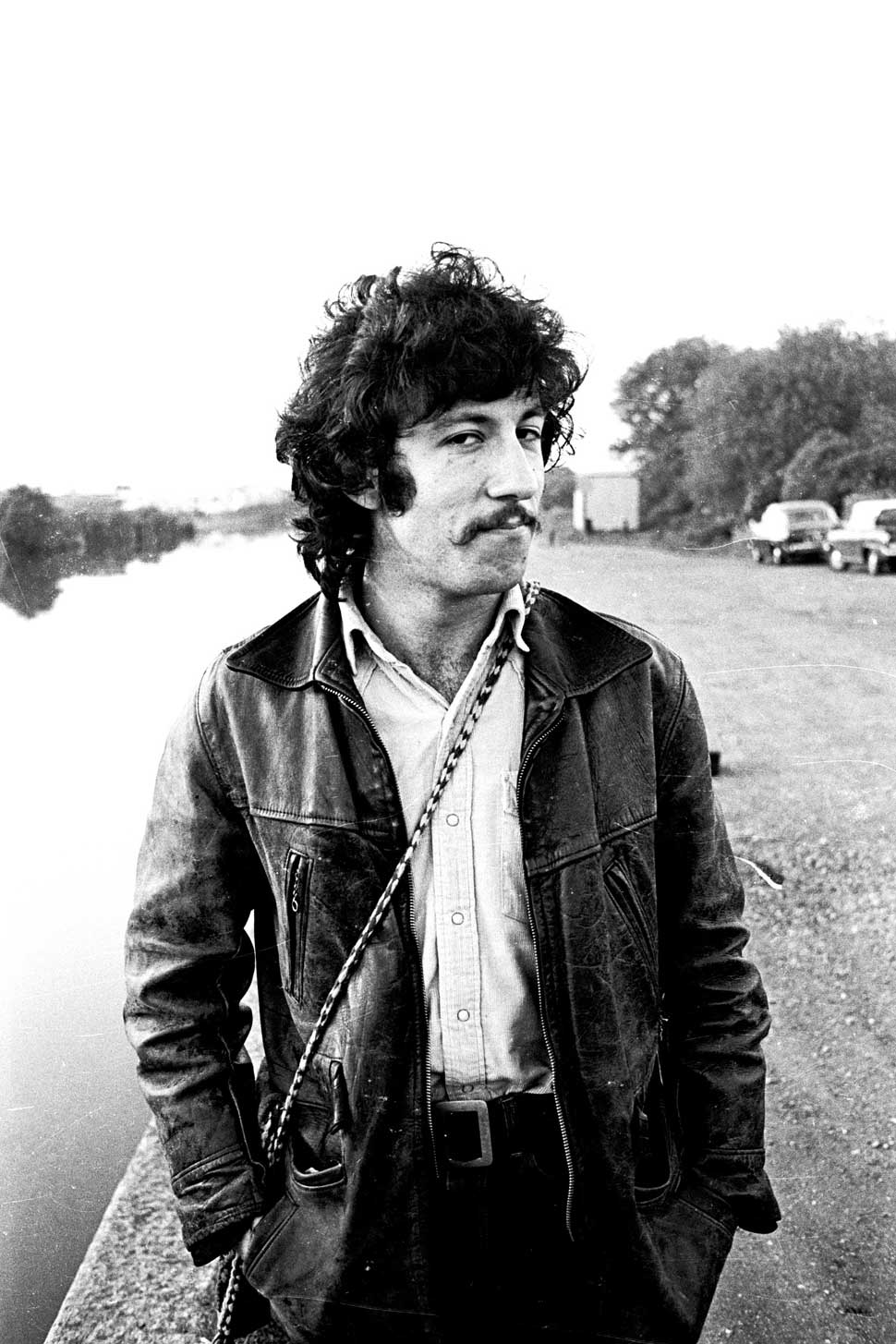

Peter Green was, arguably, the most underrated guitarist of the British mid-60s blues boom, consistently relegated to a position somewhere below the holy triumvirate of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.

He deserved better. He wrote some of the most memorable blues-based songs of the 60s, created some of the genre’s most imaginative guitar licks, and established a band that by the end of the decade was out-selling The Beatles and the Stones.

Born in London’s East End into a poor Jewish family, he was turned on to the possibilities of guitar at the age of 11, in the skiffle era of the mid-50s. His brother Len acquired a cheap Spanish guitar and showed young Peter a few chords. Before long, it was Peter’s guitar.

This is the story of how it all began for Peter Green, his first recordings, and the creation of Fleetwood Mac.

August 11, 1965: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, featuring Eric Clapton, play at Putney Pontiac Club in south-west London. Shortly after this gig, Clapton unexpectedly disappears to Greece for a two-week holiday.

John Mayall: I guess Eric just became bored with it. So he decided to get some friends together and go off to Greece. For me it was panic stations, because we’d come to rely on him so much and there were so few people to choose from as a replacement.

I got a lot of replies to an ad I put in the Melody Maker, so I was auditioning different players every night, letting them sit in to see how they worked out. Then Peter came up to me during a gig at the Flamingo in Wardour Street and was fairly forceful, very insistent that he was better than the guy I had on stage that night, so I gave him a shot. And he was quite right, of course.

Mike Vernon (Blue Horizon label founder and producer): Peter was an unknown quantity at this time. He had played in several local bands, the best known of which was perhaps The Muskrats, but he was not a big name.

Peter Green: John said I could play a little bit, and he said: "You’ve got the feeling", or something similar. Anyway, he let me on the train.

August 25, 1965: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, featuring Eric Clapton, the guitarist newly returned from Greece, play at Putney Pontiac Club.

John Mayall: Unfortunately it was only a couple of weeks before Eric came back from Greece. Eric returned with a tan, and Peter was out again. Peter wasn’t very pleased about that, but that was the way it was.

Peter Green: I was only there for a week, and then I went with Peter B’s Looners.

December 24, 1965: Georgie Fame And The Blue Flames, supported by instrumental band Peter B’s Looners, led by organist Peter Bardens, play at the Flamingo. As well as Peter Green, the group also includes drummer Mick Fleetwood, both of whom will become founder members of Fleetwood Mac.

Mick Fleetwood: Peter came to audition… We were a very simple instrumental band, a lot of Booker T, Mose Allison. He had a great sound, as they say, but me and the bassist, Dave Ambrose, didn’t think he knew enough about the guitar. He only played a couple of licks, variations on a theme, Freddie King. To Peter Bardens’s credit, he pulled me aside and said: “You’re wrong. This guy’s special.”

April 29, 1966: Peter B’s Looners play at the Carousel Club, Farnborough, with an augmented line-up including vocalists Rod Stewart and Beryl Marsden. They have been brought in at the behest of Flamingo owners Rik and John Gunnell, hoping not just to expand the band’s musical range but also to create a white soul ‘supergroup’.

Dave Ambrose (bass): When Rod Stewart and Beryl Marsden came in as singers, the band changed to Shotgun Express, doing mainly soul and Tamla Motown songs.

May 6, 1966: Shotgun Express play at the Beachcomber club in Nottingham.

Beryl Marsden: The music hadn’t happened organically. We had been rather manufactured. There was a lot of money out there to be earned in the clubs we played, like the Flamingo in Soho, and the Ram Jam Club in Brixton, but we didn’t see big wage packets at the end of the hard week’s work, and that led to discontent, too.

Dave Ambrose: We did a single on Columbia [I Could Feel The Whole World Turn Round] which was a minor hit. But shortly after a lot of soul searching on his part, Peter left.

June 17, 1966: With Eric Clapton having abandoned Mayall’s Bluesbreakers again, Peter Green is brought in to replace him once more.

John Mayall: With Peter back in the band, the way we played stayed pretty much the same. As long as you have the same rhythm section, then things don’t change that much. It’s when you lose a bass player that you’re in trouble.

Peter Green: I bumped into John Mayall on the road and he said: “Eric Clapton’s going to form Cream, with Ginger and Jack. Do you want to come with me and get some experience? And be a blues band again instead of trying to be Booker T & the M.G.’s?”

John Mayall: He was a little hesitant at first because he’d been offered a job with Eric Burdon which entailed going to America, which Peter had always wanted to do, but the music Burdon was playing wasn’t as attractive to Peter as playing blues, so he opted to come back with me.

July 22, 1966: John Mayall’s new album, Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton – recorded before Green replaced Clapton – is released.

John McVie (bass): It was done at Decca studios in West Hampstead in less than a month. We played together a lot as a band, so we’d just go in and do takes live, with no overdubs. And as soon as the session was finished, we’d be out to gig.

After the album came out, a strange situation developed, because this upstart guy named Peter Green started playing with Mayall. There were guitar style wars going on between them; all that stuff about ‘Clapton is God’ being sprayed on the walls was real!

July 24, 1966: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers play their first proper gig with Peter Green in the band, at the Britannia Rowing Club, Nottingham.

Mick Fleetwood: He went immediately for the human touch. And that’s what Peter’s playing has represented to millions of people – he played with the human, not the superstar, touch.

October 11, 1966: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers (Mayall, Green, McVie and drummer Aynsley Dunbar who had replaced Hughie Flint) are in Decca studios with producer Mike Vernon, recording the A Hard Road album. The sessions take five days in total, spread over a month.

Mike Vernon: All three Decca studios were custom-built by Decca boffins. The smallest, number two, was used primarily for pop and group sessions and had a really cool vibe… It was compact, and vision between the control room and the main studio area was excellent. The sound achieved was never less than great, but it did depend largely on the engineer. Working with engineer Gus Dudgeon made sense to me, as he was very much into the music.

I am reasonably sure that I had not met Peter prior to his arrival at West Hampstead. Me and Gus were looking at him and thinking: “Who the hell is this? Where’s Eric?” John Mayall just said: “Oh, he’s Eric’s replacement.” I hadn’t even heard that Eric had left the Bluesbreakers. John said Peter was as good as Eric, which was a bit hard to believe. Until he plugged in, and then we thought: “Um, he can play a bit!”

Initially, Peter seemed like a very quiet and somewhat reserved kind of guy… not outspoken or aggressive in any way. He must have felt somewhat awkward, though, following in Clapton’s footsteps. As the sessions progressed, Peter became a little more certain of his role as a Bluesbreaker, especially when he was given the chance to exercise his vocal chords.

He certainly was not as reluctant to sing as his predecessor had been… He seemed to really enjoy that role, and he was very good. When I heard Peter sing The Same Way for the first time, I thought: “Wow!” Here is a great blues singer, no inhibitions about singing with an English accent, expressive and individual. I had a feeling that Peter was destined to make his mark in the music business.

John Mayall: Peter was every bit as good in the studio as he was on the road. He just nailed it. I didn’t need to give him any instructions. I chose him for his individuality, for the way he played, so why would I try to direct him? The only thing he actually wrote for the album was the instrumental, The Supernatural. That was a great piece of music.

Peter Green: Mike Vernon came up with the idea for The Supernatural. He said he’d seen this guitarist who’d played a high note, sustained it and then let it roll all the way down the neck. But I played it and I decided on the sequence.

Mike Vernon: That was a major departure in sound and feel from anything we’d done with Eric. The fluidity of his playing was quite awe-inspiring. He seemed to have a natural ability to string together notes and phrases that worked straight away.

There was little time spent on working out what he was going to play, either because he had already figured out what he was going to do in advance, or the ‘moment’ took over and it just happened. In my estimation, Peter Green was just the very best blues guitarist this country has ever produced.

February 17, 1967: John Mayall And The Bluesbreakers release the album A Hard Road.

John Mayall: People often ask me about the differences between Peter and Eric, but I don’t judge guitarists by the number of notes they play, I just want them to have something moving and original to say. On a personal level, though, Peter was a much easier guy to work with than Eric. Very easy going and fun loving, great to be around. He became a really good friend.

April 19, 1967: John Mayall And The Bluesbreakers record Double Trouble in London, but the track will not appear on the next album, Crusade, due to Green’s departure from the band.

Mike Vernon: John really rated Peter’s playing as well as his vocal prowess. Peter kept telling me he was fed-up with the Bluesbreakers and wanted to put his own unit together.

It just sort of snowballed, to the point where Peter was going to leave John Mayall and form his own band. He said to me: “I want you to record our records and I want them out on your label, Blue Horizon. I don’t mind if we’re with Decca, but I don’t want it on any other label but Blue Horizon.”

Neil Slaven (author and record producer): Mike and I were school friends. We’d formed a blues society at school, and in 1966 we had formed a label together, called Blue Horizon, which was mail-order to start with. We did singles at first, and then albums. If you did a hundred or fewer copies you didn’t pay tax. The next thing was that we started the Blue Horizon Club in Battersea.

Mike was already thinking about leaving Decca, and Peter had been doing slide acoustic gigs for us at the club. I remember him saying: “For two pins I’d give all this up and start a pet shop.”’ There was always this other side to him that was detached, as if he was watching himself going into it.

Jeremy Spencer (guitarist, Fleetwood Mac): In early spring of 1967, I was playing guitar in the Levi Set, in Lichfield, Staffordshire. Unbeknown to me, my friend Phil had answered an ad in Melody Maker, which said that Mike Vernon was scouting Britain for blues talent. Mike came up to see us, and we did a thirty-minute set, and he was impressed and enthusiastic.

He later arranged a session at Decca for us to record about four tracks. While there, Mike told me that Peter Green was quitting John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers to form his own band and wanted to find another guitarist. Mike then arranged for us to play for half an hour between the sets of an upcoming John Mayall gig at Birmingham’s Le Metro club, so Peter could see and hear me play.

June 11, 1967: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers play at Le Metro, Birmingham, supported by the Levi Set.

Jeremy Spencer: I walked up to Peter to introduce myself. He said: “Jeremy? Jeremy Spencer?” before I said anything. I said I was, and asked him if he listened to Elmore James. He said: “Yes, all the time. Do you listen to BB King?” I said I did, and we chatted until it was time for their set.

I had seen John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers with Peter Green some months previously and had enjoyed it. Anyway, the Levi Set played for about half an hour between Mayall’s sets. I was happy that a good time had been had, but I pretty much discounted any idea of Peter wanting me in his new band.

To my surprise, however, Peter asked if I wanted a drink, and as we stood by the bar he talked as though I was already in it! He was saying stuff like: “Well, you can do a couple of Elmore things and then I do a couple of BB’s and so on like that…” I finally said: “Are you serious? Do you like what I play?” He said I was the first guitarist that made him smile since Hendrix! Knowing that Peter disdained speed-freak guitar playing, I said: “But he’s fast. I’m not.” He said: “It’s not the amount of notes you play, it’s what goes into the notes.

Then he showed me a page that he had written in his notebook on his way up to Birmingham. It was like a prayer that said something like: “I can’t go on with this music like it is. Please have Jeremy be good.”

Peter Green: I could see he was a little villain, you know? I thought I’d give it a try Neil Slaven: It was Jeremy and Mick who initiated all the madness in Fleetwood Mac. Peter seemed to enjoy it, but he didn’t really join in. But Peter needed someone like Jeremy around to inject something extrovert into gigs that he knew he couldn’t provide.

June 15, 1967: Peter Green quits John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

John Mayall: I was disappointed when Peter left, because he was really a special player, but his heart wasn’t in it so much, because we were leaning more towards jazzier elements.

Mike Vernon: I don’t think Peter found it that easy to be the ‘boss’ of Fleetwood Mac. There were a lot of issues at the onset. He couldn’t get John McVie to leave Mayall, and so Bob Brunning took the bass player spot. I do think that Mick also played an important part in holding the unit together. He had a keen sense of how things should be done and, in that area, he and Peter usually agreed.

Mick Fleetwood: From the beginning, he [Green] was a stickler about it not being all about him, but all about the band. That spirit was so important. We had no manager, so we did everything ourselves, and Peter did all the negotiations with Blue Horizon. Peter and I came from very different backgrounds. He was an East End lad with a chip on his shoulder – a Jewish boy who got beaten up. He got away from it, but it caught him up in the end when it all went wrong

August 14, 1967: Fleetwood Mac play their debut gig, on the third day of the National Jazz and Blues Festival, Windsor. Cream, Donovan, Jeff Beck, Alan Bown, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Chicken Shack and Blossom Toes are among the others on the bill.

John McVie: I wasn’t the bass player with Fleetwood Mac that night. I was playing with John Mayall, who was headlining. Peter Green was harassing me to join the band, and I said: ‘No, I’m fine playing with John’.

Stan Webb (guitarist, Chicken Shack): Peter and me were talking about the price of beer. Peter was wearing a white T-shirt and blue jeans, and Eric Clapton came over to us wearing a bedspread, rings on every finger, his frizzy hair sticking out six inches, and said to Peter: “You’ll never be a star if you dress like that.” Peter just smiled. And that sums it up.

Jeremy Spencer: Peter was straightforward, intuitive and a deep thinker. I think I brought to the band a kind of happy-go-lucky bawdiness, I suppose, but we related on musical and even what could be termed ‘mystical’ wavelengths. We still do, in a similar way, during our infrequent interactions on the telephone.

August 28, 1967: John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers play at the Marquee club in London. It will be John McVie’s last gig with the band.

John McVie: At the time, John had horn players in the band. We were rehearsing at some club, when John turned to one of them and said: “Okay, just play it free-form there.” I said, with typical blues snobbishness: “I thought this was a blues band, not a jazz band!” I immediately went across the street, called Peter, and asked if he still wanted me to join up. I joined Fleetwood Mac in September sixty-seven.

September 9, 1967: In a secret session at Decca studios in New Bond Street, London, Fleetwood Mac record three tracks: I Believe My Time Ain’t Long, Rambling Pony and Long Grey Mare.

Mick Fleetwood: Mike used his key to the studio to record us after hours. Mike Vernon: We recorded it extremely late at night, in the big studio at Decca. We shouldn’t have been there, when nobody at Decca knew we were doing it.

September 19, 1967: Fleetwood Mac play at Klook’s Kleek in West Hampstead, London.

Mike Vernon: I spent many hours following them around the club and university circuits. Seeing them working in front of an audience and gauging the latter’s reaction to new and old material helped in deciding what to record. In summary, I would say that Peter had to work at being the ‘boss’… Once he was at ease with that situation, everything moved forward at a faster pace and with better results.

Mick Fleetwood: Peter would come over and whip me! “It ain’t fuckin’ swingin’! You ain’t puttin’ it where it should be!” He would treat me like a dog, but that’s all it took. “I know you can do it, just do it.” “Just feel it, buddy!” Everything I am musically, I owe to Peter. I am more capable technically than I appear, but that’s a lesson well learnt from this man: less is more, more is less.

November 3, 1967: The first UK single by Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, I Believe My Time Ain’t Long, is released.

Mike Vernon: The very first demos had been offered to Decca, and they weren’t rejected, but they wouldn’t put the record out on the Blue Horizon label. So we offered it to CBS, who took it and took the label identity as well. But once that record came out and was something of a success, I got the dreaded phone call from the seventh floor at Decca, got called in and was told: “You can’t produce records for other record companies!”

I said: “Well, I did offer it to you and you rejected it, so I took it to someone else.” And they said: “Okay, fair enough, but you can’t do these two things at once, so you either have to resign or we’ll fire you.” So I said: “Right, I resign as of now,” went away, and about three weeks later I came back and signed an independent production deal with Decca.

Mick Fleetwood: Peter saved my bacon on more than one occasion. One night at the Marquee, we’d had a few drinks, we were jamming, and I’d got over-adventurous and came out of it the wrong way. I’d lost track of whether I was on the off-beat or the on-beat, but Peter always knew, so he was laughing at me. I was completely lost.

But I kept going, of course, until Peter came back, grabbed my wrist and put me back in time. He was my mentor, my partner and my friend. That was my training ground. I didn’t really have a lot of confidence.

I was going around with Aynsley Dunbar, the drummer of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, who was an incredible drummer, and still is. I had sort of a humorous self-effacing element to me, and Peter was a great encourager of it. He told me that it was one of the best things about my playing.

November 22, 1967: Fleetwood Mac are in CBS Studios, New Bond Street, London, recording Merry Go Round, Hellhound On My Trail, I Loved Another Woman, Cold Black Night, The World Keeps On Turning, Watch Out, A Fool No More, You’re So Evil and Mean Old Fireman. Most of these tracks will appear on their debut album, Fleetwood Mac.

Mike Vernon: I don’t think Peter was very interested, at that time, in the recording process. That was my job, along with the engineer. He fully understood the basics, though. I think he felt that his job was to create the music and the atmosphere that was essential to get the best results. If I had any qualms, it would only have been that they could sometimes be infuriating with their persistent ‘messing around’.

Mike Ross (engineer): The first time I met Peter was when they walked into our studio, which was on the first floor above a fashion shop. It wasn’t a great studio, but we made it work. It had been a ballroom in the early 1900s, so it had very high ceilings, which we’d had lowered, otherwise drum sounds would just bounce around everywhere.

As a staff engineer for CBS, I was doing pop bands like The Marmalade and The Tremeloes, so this was my first real exposure to blues. Peter was obviously the boss, he was very verbal. The two people I remember doing most of the talking were Mick Fleetwood and Peter Green. They were the guys in charge. The others were more quiet, a bit laid back. Mick and Peter used to give me lifts home after sessions, because I lived at Holland Park and they were in Shepherd’s Bush, and that’s how I started to realise what good friends they were. They were very close.

Those sessions were mainly recorded live, with the band DI’d straight into the mixing desk. We were using a four-track recorder, but they wouldn’t let us record them separately, which I would have preferred, to achieve a better sound. Peter didn’t want a ‘better’ sound, he wanted it to sound as near as possible to the way they sounded on stage. So they would all play at once, with Peter singing and playing simultaneously.

As a result, there was quite a lot of spill across the tracks, which I think did add to the roomy sound. It was absolutely live, but it wasn’t dirty enough for them. There were lots of conversations about how Chess Records sounded. They even brought in a couple of Chess seventy-eights to illustrate the sound they wanted. In fact, when they heard the tapes they were really not happy with them, but there wasn’t much we could do about that except maybe remix them a little by changing the levels on the tracks.

They wanted it to sound rougher. But Mike Vernon was able to talk them out of that, so we didn’t really get close to what they wanted until the second album, Mr Wonderful, where we got them to bring their stage amps and speakers into the studio and play through them.

December 5, 1967: John Mayall is in studios in London working on the tracks Jenny and Picture On The Wall, with Peter Green on guitar.

John Mayall: Even after Peter left we remained great friends, so I would go out to see him playing live in Fleetwood Mac, which was a very exciting band – mostly my old band. But you can’t stand in the way of progress.

December 11, 1967: Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac are in CBS studios recording My Heart Beat Like A Hammer, Shake Your Money Maker and Leaving Town Blues. The first two of these tracks will appear on Fleetwood Mac.

Mike Ross: I was impressed by the quality of their songs, and also by the speed at which they worked. Most of the songs would be just two takes, or even one in some cases. They took it all quite seriously, no messing around once they got down to work. Mike Vernon was quite a strict producer. I think they knew better than to mess around with him being there.

The only one who was a bit of a humorous character was Jeremy Spencer. He just wanted to be Elvis Presley, and he’d come out with a bit of Heartbreak Hotel or something in the middle of a session. He wanted tape echo on everything. He was a rock’n’roller at heart, more so than a blues man, but his Elmore James guitar style was amazing.

Jeremy Spencer: Peter had asked me on the band’s onset if I ever wrote my own material, and I had told him that I didn’t. The problem was that I was uninspired with getting anything new. No wonder he eventually welcomed [guitarist] Danny Kirwan’s creative addition.

February 16, 1968: Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac release their debut album, Fleetwood Mac, on Blue Horizon. It will peak at No.4 in the UK and remain on the chart for 37 weeks.

Mike Vernon: Peter was able to really put good melodies together within his playing, probably more so than Clapton, who had a much more rhythmical approach, he never got out of the groove. Whereas Eric had energy in his playing, Peter had a deftness, a touch and a more melodic style, and actually at that time he probably had a deeper blues than Eric.

Melody Maker (review): “The is the best English blues LP ever released.”

What happened next

Seeking to expand the band’s musical horizons, in 1968, Green brought in a third guitarist, 18-year-old Danny Kirwan. The major hit singles started in 1969 with Albatross, Man Of The World and Oh Well.

Green’s well-documented and disastrous encounters with LSD resulted in the demise of the first incarnation of Fleetwood Mac, but the remnants relocated to the US where, eventually, with a change of line-up – which included just Mick Fleetwood and John McVie from the old band – and musical direction, they became one of the most successful rock bands of all time.