Almost 10 years to the day since the release of The Dark Side Of The Moon, Pink Floyd’s album The Final Cut was released. A decade earlier, the material for Dark Side had been worked up thoroughly on the road, and all four band members had writing credits on the record. With The Final Cut, the group – a trio, following the sacking of keyboard player Rick Wright – had become, through default more than by design, a method of carriage for the words and music by de facto leader Roger Waters alone, with session musicians featured heavily throughout its recording.

The album had few discernible hooks, no standout commercial moment, and Floyd never played anything from it live. Initially that didn’t stop the Floyd juggernaut. Fans worldwide had been waiting three and a half years for a new album, their longest wait to date. And so, on its release in March 1983, The Final Cut became Pink Floyd’s first UK No.1 album since 1975’s Wish You Were Here. Rolling Stone gave it the full five stars, and suggested that it might be “art rock’s crowning masterpiece”.

But the juggernaut would soon jackknife. The Final Cut disappeared almost as soon as it arrived, leaving the album, a single and a 19-minute ‘video album’ as its only footprints. There were no promotional appearances, no group publicity photographs, no tour. But it soon became Exhibit A in the painful, public breakdown of one of the world’s biggest and most successful groups.

If the album featured at all in later interviews by both Roger Waters and David Gilmour, it was portrayed as coming from a period of abject misery.

“That’s how it ended up,” Gilmour told Rolling Stone’s David Fricke in 1987. “Very miserable. Even Roger says what a miserable period it was – and he was the one who made it entirely miserable, in my opinion.”

“It came and died, really, didn’t it?” says Willie Christie, who shot the album’s cover photo. Christie has great insight into the album and the period. Waters was his brother-in-law, and at the time Christie was living in an outhouse over the garage at Waters’s house in Sheen, “after a relationship had gone south”.

“Because the break-up was on the horizon,” he adds, “I think David was finding it very tough; Roger for different reasons. That was a great shame. David had said publicly that the songs were off-cuts from The Wall. Why regurgitate? I never saw it like that. I loved it and thought there was some great stuff on it.”

While it would probably be a perverse fan who would name The Final Cut as their favourite Pink Floyd album, it’s certainly worth a lot more credit than it’s usually given. Yes, the album is the greatest example of high-period megalomaniac Waters. However, for all his writing and singing, it needs to be taken as a Floyd release, and not a solo Waters one – it has some of Gilmour’s best guitar solos, and drummer Nick Mason curated some of the best sound effects in Floyd’s career.

As a protest album, it’s one of the strongest ever in British rock. Had it been made by, say, Elvis Costello, Robert Wyatt or The Specials, it would have far more retrospective gravitas.

‘What have we done to England?’ Waters sings on opening track The Post War Dream, as a brass band, that most quintessentially British sound, plays out. It locates the album squarely in the post-Falklands-invasion landscape of 1982, while looking back to the WorldWar II beachheads of 1944. As Cliff Jones noted in Echoes: The Stories Behind Every Pink Floyd Song, it was “the most lyrically unequivocal of all Pink Floyd albums”.

Moreover, the album is phenomenally significant in the group’s career. Had it been a far better experience and a bigger seller, it might have allowed Floyd to conclude, or perhaps continue, on a triumphant, cordial high. Instead it left a nagging sense of unfinished business, which led to the split, the commercial triumph of the Gilmour years and the group’s enormous afterlife.

The genesis of The Final Cut is well known. Some of its material dates from five years previously, when Waters came up with the original cassette recording of The Wall in the summer of 1978.

He had written around three albums’ worth of material. He was driven in a way that the other band members, who seemed to want to escape Floyd at the time, simply were not. To Waters it was like picking hard at a scab – he knew he shouldn’t, but he just had to explore further this monster that he had helped create.

Pink Floyd as we knew them finished on June 17, 1981 at London’s Earls Court arena, when the last of the 31 The Wall shows ended. That year’s return to touring was to gather material for the Alan Parker-directed filmed version of The Wall.

There were offers – with considerable irony – for the band to tour stadiums. Waters, of course, ran a mile from them. Meanwhile, serious contemplation was given to the idea of playing the shows with Andy Bown, of Floyd tribute group the Surrogate Band taking Waters’ place.

“I was asked if I would be interested if the situation arose,” Bown says today. “I said yes, I would be.” But the idea was quickly vetoed by Waters. There was talk of a soundtrack album to the Parker film, but there was hardly a great deal of material: versions of In The Flesh (with and without the question mark) performed by the film’s Pink, Bob Geldof; The Wall out-take When The Tigers Broke Free; and What Shall We Do Now?, which was left off the album.

This project evolved into Spare Bricks, where these tracks were supplemented with additional The Wall off-cuts Your Possible Pasts, One Of The Few, The Hero’s Return and The Final Cut. However, when Argentina invaded the Falklands – the British-ruled islands in the South Atlantic in April 1982 – and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher sent a task force to counteract this, Waters suddenly had his subject matter.

The pointlessness of the ensuing 74-day conflict, resulting in the loss of 907 lives, evoked again the death of Waters’ father Eric in World War II, at Anzio in 1944. Waters relished the merging of the past and the present. He was going to write a modern requiem.

And so Spare Bricks became The Final Cut. Its title was a Shakespearean reference to Julius Caesar being stabbed in the back by Brutus: “This was the most unkindest cut of all.”

“The Final Cut in film terminology is the finished article,” Gilmour explained in 1983. “When you stick all the rushes together basically in the right order, you call it the ‘rough cut’, and when you’ve cleaned it up and got it perfect you call it the ‘final cut’. It’s also an expression for a stab in the back, which I think is the way Roger sees the film industry.”

Waters’ frequent run-ins with director Alan Parker on the making of the film are no secret. It was also clear that the members of Pink Floyd, never the chummiest of groups, were growing ever further apart. The UK premiere of The Wall on July 14, 1982, at the Empire Theatre in London’s Leicester Square, was the only time the three-man Pink Floyd – no one knew yet that Rick Wright was no longer in the band, with the party line being that he was ‘on holiday’ – were ever seen together in public.

When The Tigers Broke Free (originally titled Anzio, 1944), issued as a single in July 1982, was full of pathos and huge in its intent. Not since Apples And Oranges, released back in 1967, had so many eyes had been on the chart performance of a Floyd single, Tigers being their first single since Another Brick In The Wall, Part Two in 1979.

Tigers, which was fundamentally Waters with the Pontarddulais Male Voice Choir and an orchestra, was labelled as being from The Final Cut. Ironically, it didn’t make it on to the album until the tracklisting was reconfigured for CD in 2004. Tigers reached only No.39 in the UK.

After the release of single, Waters told Melody Maker in August 1982: “I’ve become more interested in the remembrance and requiem aspects of the thing, if that doesn’t sound too pretentious.”

After then arriving at The Final Cut, “the whole thing started developing a different flavour, and I finally wrote the requiem I’ve been trying to write for so long”.

Requiem For The Post War Dream was to become the subtitle for the album. By this point, Waters said the group had “got to the stage of a rough throw-together of all the work we’ve done so far”.

After the US premiere of The Wall film and a holiday, Waters got back to work in earnest that autumn. The sessions began in July and lasted through to that Christmas. Fittingly, it’s a truly UK-centred album, with sessions at Abbey Road, Olympic, Mayfair, RAK, Eel Pie, Audio International, Gilmour’s home studio Hookend and Waters’s home studio The Billiard Room.

With The Wall co-producer Bob Ezrin excommunicated, Michael Kamen and James Guthrie co-produced with Waters and Gilmour. With Mason racing cars and presiding over a failing relationship while beginning a new one, Gilmour struggling to write new material, and Wright’s departure now just a memory, Waters was in a frantic hurry to complete the album that had by now taken on a whole new lease of life.

“I started writing this piece about my father,” he said in 1987. “I was on a roll, and I was gone. The fact of the matter was that I was making this record and Dave didn’t like it. And he said so.”

‘Dave didn’t like it’ has become the shorthand for The Final Cut. After a cordial start, it soon became apparent that Waters and Gilmour would need to work separately. Engineer Andy Jackson would work with Waters, and Guthrie would work with Gilmour, and occasionally they’d meet up.

I never, never wanted to stand in the way of him [Roger] expressing the story of The Final Cut. I just didn’t think some of the music was up to it.

David Gilmour

“The relationship was definitely frosty by that stage,” Jackson told radio program Floydian Slip in 2000. “I don’t think anyone would want to deny that. So, the time that Dave – Dave in particular – and Roger were in the studio together, it was frosty. There’s no question about it.” Yet this frostiness made for great art.

There was innovation too. Italian-based, Argentine-born (which no doubt would have appealed to Waters’s sense of humour) audio inventor Hugo Zuccarelli had approached the group to try out his new ‘Holophonic’ surround sound that could be recorded on stereo tape. For a group so associated with their audio pioneering, this was a positive boon.

The system used a pair of microphones in the head of a dummy. Zuccarelli played Mason, Gilmour and Waters a demo of a box of matches being shaken that sounded as if it was moving around your head. The group were of one mind to use the system. Mason began to gather the sounds in the Holophonic head (which, as he noted in his Floyd history Inside Out, “answered to the name Ringo”).

He duly recorded Tornado aircraft at RAF Honington, the sounds of cars passing, the wind, and various ticks, tocks, dogs, gulls, steps, shrieks and squawks. On the album, sound effects careened between left and right channels. The missile attack at the start of Get Your Filthy Hands Off My Desert is arguably the greatest sound effect on any Pink Floyd record.

Ray Cooper played percussion, Raphael Ravenscroft added saxophone, and on closing track Two Suns In The Sunset veteran drummer Andy Newmark took Nick Mason’s place. It took two players to replace Rick Wright: Michael Kamen on piano, and Andy Bown on Hammond organ.

“It was wonderful to work for them in that live situation. It’s rare to meet a rock band that know how to behave,” Bown recalls. “And the Floyd organisation treated the hired guns very well indeed. Recording is different – you’re not living with each other in the same way. I remember almost nothing from those sessions. I wonder why.”

Waters’s exacting attempts at nailing a vocal recording led to the well-reported incident of Kamen doing a Jack Nicholson in The Shining, writing furiously in the control room. When Waters went to investigate what he was doing, he saw that Kamen had written repeatedly: “I must not fuck sheep”. According to Andy Bown, Kamen was “a lovely cuddly bear with a wacky sense of humour”.

“It was obvious Roger was making the running,” Nick Mason said in Inside Out, of a period of recording at Mayfair Studios. “Roger is sometimes credited with enjoying confrontation, but I don’t think that’s the case. I do think Roger is often unaware of just how alarming he can be, and once he sees a confrontation as necessary, he is so grimly committed to winning that he throws everything into the fray – and his everything can be pretty scary… David, on the other hand, may not be so initially alarming, but once decided on a course of action is hard to sway. When his immovable object met Roger’s irresistible force, difficulties were guaranteed to follow.”

“I was in a pretty sorry state,” Waters said. “By the time we had got a quarter of the way into making The Final Cut, I knew I would never make another record with Dave Gilmour or Nick Mason.”

Gilmour said in 2000: “There were all sorts of arguments over political issues, and I didn’t share his political views. But I never, never wanted to stand in the way of him expressing the story of The Final Cut. I just didn’t think some of the music was up to it.”

After much arguing with Waters, Gilmour surrendered his producer credit on the album – but not his share of producer royalties. He was even to say: “It reached a point that I just had to say: ‘If you need a guitar player, give me a call and I’ll come and do it.’”

In 1983 he said: “I came off the production credits because my ideas of production weren’t the way Roger saw it being.”

“I was just trying to get through it,” Gilmour told me in 2002. “It wasn’t pleasant at all. If it was that unpleasant but the results had been worth it, then I might think about it in a different way. I wouldn’t, actually. I don’t think the results are an awful lot… I mean, a couple of reasonable tracks at best. I did vote for The Fletcher Memorial Home to be on Echoes. I like that. Fletcher, The Gunner’s Dream and the title track are the three reasonable tracks on that.”

Overlaid with Waters’s disgust at the Falklands War, the collapse of the socialist post-war dream, and grieving for the father he never knew, the narrative of The Final Cut focuses on the figure of the teacher from The Wall, who had been a gunner in the war, staring down modern life. The central character of The Wall, Pink, makes an appearance on the title track. Waters is frequently self-referential in his choice of words. For example, ‘quiet desperation’ and ‘dark side’, two most Floydian phrases, are used.

Of the original album’s 12 tracks, The Hero’s Return and The Gunner’s Dream are two of Waters’s finest moments side by side: full-bleed paranoia, with his unlimited capacity for beauty and empathy. The Hero’s Return began life as Teacher, Teacher from The Wall. The band’s demo from January 1979 has a synth drone, with Gilmour on loud slide guitar; here, the hero is haunted by images of the war he can’t discuss with his wife.

On The Gunner’s Dream there’s little guitar but plenty of saxophone, so much a feature of 1973-75 Floyd. Here, as with a lot of the album, Waters’s voice is the lead instrument. The song examines the sudden powerlessness of a situation when confronted by the jackboot. Referencing war poet Rupert Brooke, Waters delivers one of his finest vocal performances. It also introduces the imaginary character Max, an in-joke name for producer Guthrie from the sessions.

Journalist Nicholas Schaffner says: “In some ways The Final Cut qualifies as Roger’s equivalent of John Lennon’s highly acclaimed primal scream LP [John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band], released in the wake of The Beatles’ 1970 disintegration.”

And the screaming doesn’t stop. A decade and a half after his wails on Careful With That Axe, Eugene, possibly Waters’s career-best bellow is on The Gunner’s Dream, where he howls for a full 20 seconds. Rolling Stone said it contained some of the most “passionate and detailed singing that Waters has ever done”. And it’s certainly there, as he enunciates every vowel as if his life depends on it.

The Fletcher Memorial Home, where ‘colonial wasters of life and limb’ assemble, delivers another standout moment, with Waters giving tyrants past and present the chance to get together before applying a final solution to them. Gilmour’s solo and Kamen’s beautiful brass arrangement enhance the song’s gravitas.

While the title track is similar to Comfortably Numb in its arrangement, Not Now John is the album’s rocker. It’s a call and response between Gilmour and Waters – one as the jingoistic rightwinger so celebrated in the early 80s, the other attempting reason. The US, sensing the one song that resembled conventional rock (complete with Gilmour’s ultra-Floyd guitar work), suggested a radio recut, with Gilmour and the backing vocalists singing ‘stuff’ loudly over the song’s obvious use of the word ‘fuck’.

It was issued as a single, accompanied by a Willie Christie-directed video, in May 1983 and scraped into the UK Top 30. Album closer Two Suns In The Sunset was inspired by Waters’s recent viewing of the banned docudrama The War Game. In the end the hero drives off and sees a nuclear explosion, a result of someone’s anger spilling over to the point where the button is pushed. He now understands ‘the feelings of the few’. As the explosion comes, Waters suggests: ‘Ashes and diamonds, foe and friend, we were all equal in the end.’

The final track from ‘the original Pink Floyd’ ends with a session sax player, a session drummer, and a producer playing piano. By then it seemed that even Waters had been removed from his own story. The surrogate band had taken over.

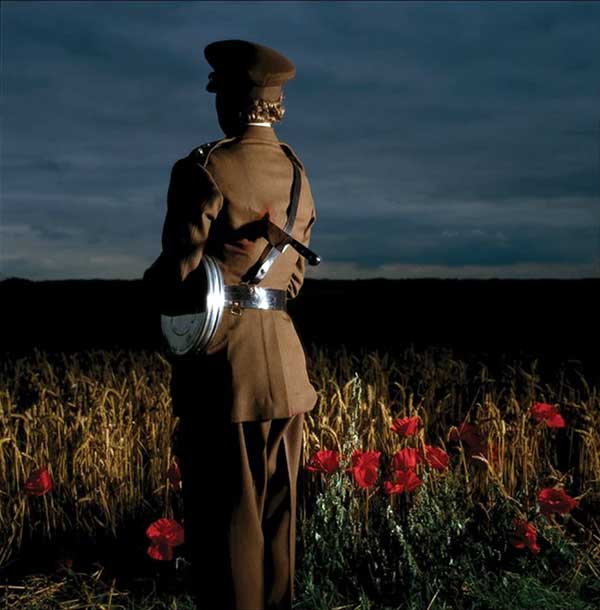

Even designers Hipgnosis, long-time Floyd collaborators, and cartoonist/illustrator Gerald Scarfe were now surplus to requirements. Scarfe has said he had done a test version of a cover for The Final Cut, but Waters himself oversaw the artwork with graphic design company Artful Dodgers. His brother-in-law, Vogue photographer Willie Christie, was brought in to take the photos for the sleeve. With Christie Waters’s house guest at the time, the pair discussed the concept at length.

“We were talking about it all the time from conception,” Christie says. “Roger asked me to do the stills. They came out of ideas we had talked about – poppies featured a lot because of the theme of it. I did the stills – the poppies and the strip of medals – in November 1982. The field was near Henley. We needed a field of corn, and I’d done a Vogue shoot down there in 1977. A prop company called Asylum made me up some poppies, as real poppies don’t last.”

Asylum also made two uniforms, complete with the knife in the back. Christie’s assistant, Ian Thomas, modelled the outfit, holding a film canister under his arm. “That was the whole idea of the knife in the back and the film canister,” Christie says. “That [Alan] Parker had stabbed him [Waters] in the back.”

In another shot, Thomas is seen lying dead in the poppy field, watched over by Stewart, the Waters’s pet spaniel. In the gatefold, Thomas can be made out in the distance, while the outstretched hand of a child holds poppies. The sleeve also contains an image for Two Suns In The Sunset, and the Japanese welder (another assistant, future fashion photographer Chris Roberts) for Not Now John which was shot in Christie’s London studio.

Christie recalls showing the group his work in progress: “David hadn’t been involved or consulted. I slightly found myself in the middle. It was a little bit awkward, as I’d been talking to Roger. But David’s a really good bloke, a genius. It was a little: ‘Oh, David, sorry I haven’t showed you. It’s not me,’ sort of thing.”

Gilmour looked at the photographs and then told Christie: “Well actually, the knife wouldn’t go in like that, it would go in sideways, as your rib cage wouldn’t allow it to go in straight, vertical.”

“Roger poo-pooed that, thankfully, as I thought I’d have to have the thing remade and have to reshoot it. It might have looked a bit strange if you had the knife flat. Aesthetically, whenever you see a knife in the back it’s always vertical, not horizontal. So it’s a good point, but it wasn’t given much credence.”

The cover image is a powerful close-up of a serviceman’s lapel, showing a poppy and his medals. The back of the sleeve listed just three members of Pink Floyd. This was the first time the wider world became aware that Rick Wright was no longer a member of the group – and that this was clearly a work ‘by Roger Waters, performed by Pink Floyd’.

It’s difficult now to convey just how exciting the release of The Final Cut was, on March 21, 1983. It shot to No.1 in the UK, remained in the chart for 25 weeks and sold three million copies worldwide. As well as the UK, it topped the charts in France, West Germany, Sweden, Norway and New Zealand. In the US it reached No.6.

The critics were, of course, deliciously mixed. Richard Cook wrote in the NME that Waters “picks out the words like a barefoot terminal beachcomber, measuring out a cracked whisper or suddenly bracing itself for a colossal scream… The story is pitched to that exhausting rise and fall: it regales with the obstinacy of an intoxicated, berserk commando.” The review ends with the extremely perceptive comment: “Underneath the whimpering meditation and exasperated cries of rage, it is the old, familiar rock beast: a man who is unhappy in his work.”

In Melody Maker, Lynden Barber wrote: “Truly, a milestone in the history of awfulness. Expect the usual sycophantic review in the pages of Rolling Stone.”

A week later, Kurt Loder duly obliged, with a five-star review that included: “This may be art rock’s crowning masterpiece, but it is also something more. With The Final Cut, Pink Floyd caps its career in classic form, and leader Roger Waters – for whom the group has long since become little more than a pseudonym – finally steps out from behind the ‘Wall’ where last we left him.

"The result is essentially a Roger Waters solo album, and it’s a superlative achievement on several levels. Not since Bob Dylan’s Masters Of War 20 years ago has a popular artist unleashed upon the world political order a moral contempt so corrosively convincing, or a life-loving hatred so bracing and brilliantly sustained… By comparison, in almost every way, The Wall was only a warm-up.”

"I was in a greengrocer’s shop, and this woman of about forty in a fur coat came up to me,” Waters told music journalist Chris Salewicz in 1987. “She said she thought it was the most moving record she had ever heard. Her father had also been killed in World War II, she explained. And I got back into my car with my three pounds of potatoes and drove home and thought: ‘Good enough.’”

And it was good enough. But not good enough for what Pink Floyd had become in popular perception. As Nick Mason later wrote: “After The Final Cut was finished there were no plans for the future. I have no recollection of any promotion and there was no recollection of any live performances to promote the record.”

Had there been a tour to support it, The Final Cut could have been a huge, sustained hit. There’s just something about it, like much art from that strange 1980-83 period in the UK, such as Boys From The Black Stuff or Brideshead Revisited, that when you’re locked into it it can’t fail to make you feel moved.

The early 80s, unless you lived through them, are very hard to explain. The 60s and 70s seemed clear-cut. When people do think of the 80s, it’s that later flash, brash, wedges-of-money time. We also need to review where Floyd’s 70s peers were by 1983. Led Zeppelin were long gone. Queen were licking their wounds from an ill-advised, all-out assault on disco. Genesis had gone ‘pop’. Yes were, quite by accident, about to reinvent themselves as a techno stadium monster.

It could be said that Pink Floyd were the only ones doing what they always did – or at least post-1975 Floyd. But, as said, it wasn’t enough.

Less than three months after the release of The Final Cut, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government were re-elected with a landslide majority victory, and Labour suffered their worst post-war performance.

At once, the result reinforced Waters’ concerns about the whereabouts of the post-war dream and demonstrated how out of step he was with his audience. Both main protagonists released a solo album the following year: Gilmour’s About Face, Waters his other 1978 concept idea, The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking, done with much of the same team as The Final Cut. (“That was jolly good fun,” Andy Bown recalls. “And terrific musicians to work with. Bloody good album too.”)

In October 1985, Waters issued a High Court application to prevent the Pink Floyd name ever being used again, considering it a ‘spent force’. With that, he finally had the nerve to make the final cut. Gilmour and Mason, however, did not, and the next chapter of Pink Floyd was about to begin, one that would see the band going back to stadiums and making a noise that sounded like the best of Floyd’s albums from 1971-75.

Unlike Led Zeppelin, who all but went into cold storage following the death of John Bonham, and reactivated only a good decade later, the actions that followed Pink Floyd’s loss of a founder member set the band up to become the strident prog behemoth they are today – and one that Roger Waters would eventually match with his own stadium endeavours over the past decade.