In 1972, Simon Jeffes was on holiday in the South of France when he contracted food poisoning from fish. During a high fever, he experienced a series of hallucinations, including a dystopian vision of the future. He recalled the incident in 1988.

“The next day, when I felt better, I was on the beach sunbathing and suddenly a poem popped into my head. It started out, ‘I am the proprietor of the Penguin Cafe, I will tell you things at random,’ and it went on about how the quality of randomness, spontaneity, surprise, unexpectedness and irrationality in our lives is a very precious thing. And if you suppress that to have a nice orderly life, you kill off what’s most important. Whereas in the Penguin Cafe, your unconscious can just be.”

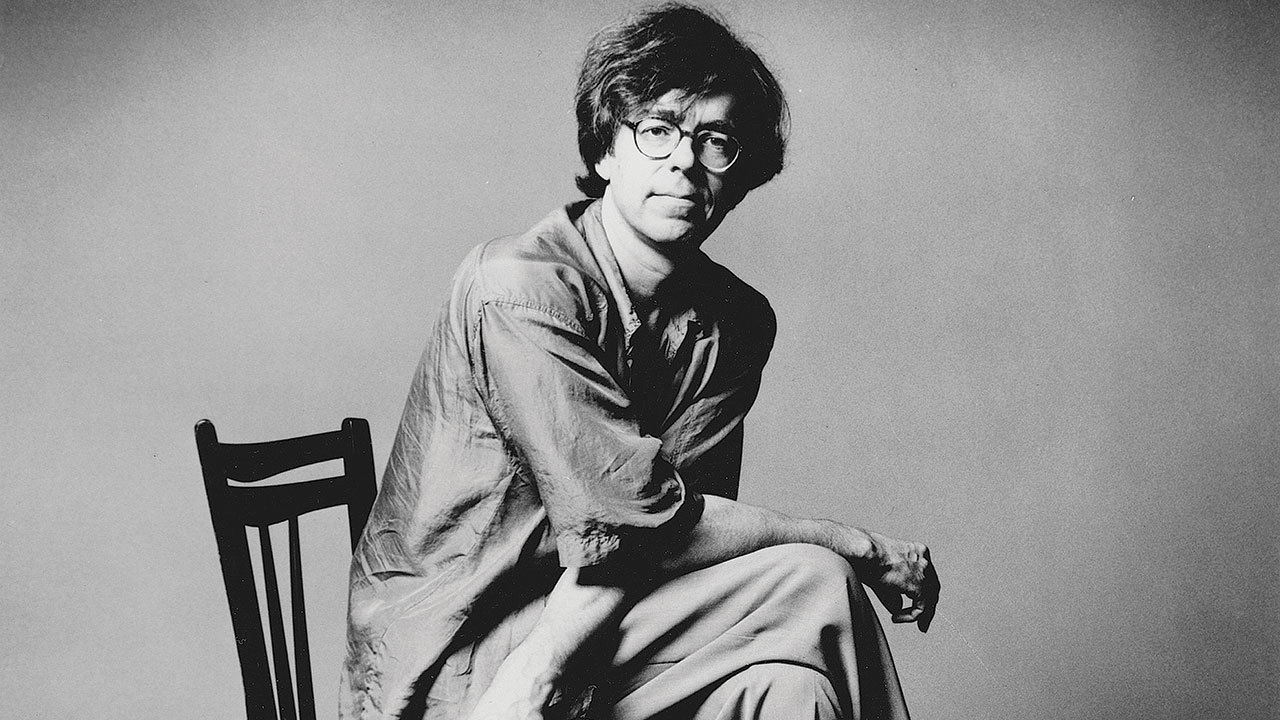

And so the idea for the Penguin Cafe Orchestra was born. This strangest of group concepts defined a mental space, which Jeffes could fill with musical ideas. While leading the instrumental ensemble, with its shifting cast of over 30 musicians, he produced some of the most singular music of the 70s and 80s, until his death in 1997, aged 49.

Jeffes started out performing in a classical guitar group, but by the late 70s he was disenchanted with both classical repertoire and rock’n’roll. His former partner Emily Young is now one of the UK’s foremost sculptors. As a teen, she had been to some of Pink Floyd’s earliest London shows. She knew Syd Barrett – “Just in passing” – and is thought to be the inspiration for the song See Emily Play. This was the milieu in which she met Jeffes.

“It was the 60s when he started being who he was in terms of a musician and composer, and leaping out of the rather dismal past,” says Young. “And in that kind of optimism, it’s similar to what Syd Barrett was doing: it’s quite English.”

So much of Jeffes’ music is hard to pin down, mercurial in nature, and full of contradictions. For example, Young is right that with its strong melodies, whimsicality, wit and generally unassuming nature, it carries a distinct feeling of Englishness. But then it’s also pervaded by the rhythms and melodic figures of Africa and South America.

“He wanted to put all that together,” says Young. “[He used] guitar and percussion, ukulele and cuatro, with the classical strings playing together so beautifully and so tight, but then there was also the looseness, the way your body can go with the rhythm.”

When asked to categorise his music in 1988, Jeffes chose the descriptions “imaginary folklore” and “Modern semi-acoustic chamber music.” Young recalls that when the Orchestra were in their early stages, one of their gigs was, fittingly, listed in the “other” category in Time Out magazine.

In the mid-70s, Jeffes’ music caught the attention of Brian Eno. Eno was setting up his Obscure record label, which served as a haven for some of the avant-garde composers of the day.

“It was a bit of a fluke,” Young explains. “Brian had these other people he was working with in a left-field zone. And then Simon turns up and what he was doing was so unlike anything else, that Brian, bless him, said, ‘We’ll do something, we’ll see what happens.’”

The Orchestra’s 1976 debut album, Music From The Penguin Cafe, features a core of four musicians with vocals by Young on From The Colonies. It was the only time she sang on record, as Jeffes decided to pursue a purely instrumental tack thereafter, but she helped define the group’s aesthetic by painting the surreal album covers which featured Penguin-headed humans in strange tableaux.

Penguin Cafe Single sounds like an old parlour tune done ragtime style, with see-sawing string figures which drop right down in a middle section of twinkling electric pianos. On first listening – like many Penguin Cafe Orchestra pieces – it feels uncannily like something that one has heard before. And as Young says, stylistically it’s almost impossible to date.

“He wanted it to be a universal pleasure so that anybody, anywhere in the world could listen to it and get as much pleasure out of it as he did,” says Young. “It was intellectually interesting, but at the same time he wanted his emotional world to sing and feel free.”

From appealing to Brian Eno in the mid-70s, in 1985 Penguin Café Orchestra appeared as the musical interlude on the BBC chat show Wogan, on which they played the jig-like Music For A Found Harmonium, which the host described as “like The Chieftains with Japanese undertones”.

Young remembers that Jeffes would sit for long periods at a piano listening to the harmonics and overtones of single notes, then those of notes played together. This fascination with sound led to the couple enjoying rather some unusual nights out.

“We’d smoke a little dope and go down to Heathrow Airport and wander around late at night, at like 1am, when there were very few people,” she recalls. “The sounds of the airport were fantastic, all these different hums and knocks, and noises coming from behind locked doors. It was the notion that the whole airport was one huge musical instrument.

“Simon was really interested in the harmonics, and how sound affects you. Sometimes you would get two different noises going at the same time and they were making a chord, and sometimes it’s major and sometimes it’s minor. There’s a click-click-click of an escalator, so you’ve got a rhythm going on at the same time as the air conditioning hum.”

Penguin Cafe Orchestra’s most experimental piece, Telephone And Rubber Band (from 1981’s Penguin Cafe Orchestra), is based on recordings of a telephone’s engaged and ringing tone. It was also their most widely heard, as it was used in mobile phone network One2One’s TV ads in the late 1990s.

The Penguin Cafe Orchestra members continued to play Jeffes’ music – some of which was composed in collaboration – after his death as The Orchestra That Fell To Earth and played a trio of memorial concerts at London’s Union Chapel in 2007, joined by Jeffes’ and Young’s son Arthur. He was thrilled to hear it live once more, the pieces being “like old friends you thought you wouldn’t see again”.

Arthur Jeffes has since headed his own band as Penguin Cafe, who play his father’s music in concert as well as his own new material. One ex-Orchestra player approached for this piece politely declined to be interviewed, feeling that their contributions were now effectively written out of history.

“I was a very inexperienced musician at that point and all the musicians had their own ideas about how the tunes should go and there was no central authority,” Arthur explains. “I wouldn’t have been able to continue with them so we just left it there. That was beautiful but we’ve closed the chapter. I think there was a general agreement that it had to be that way.”

In December 2017, Penguin Cafe played a concert to mark the 20th anniversary of Simon Jeffes’ passing, which coincided with the label Erased Tapes reissuing the Penguin Cafe Orchestra’s last album, 1993’s Union Cafe. The group played it in its entirety.

“In a funny way, learning all these pieces from Union Cafe has been a bit like playing with him,” Arthur says. “It’s been emotionally turbulent and fun. It was really interesting because there is a complexity there that I hadn’t clocked first time around.”

Arthur gives the example of Lifeboat, on which he played piano live with Neil Codling (of Suede) on cuatro. It took a while to get the timing of their respective patterns – in different time signatures – spot on, but when they did it yielded “a melodic result you wouldn’t otherwise have”.

The composition that most clearly demonstrates this relationship between rhythm and melody in his father’s music – and his impish sense of humour – is Discover America, on Union Cafe. The strings play Home On The Range and When The Saints Go Marching In at the same time, which works delightfully. This curious counterpoint produces an unexpected bonus. “There are three occasions where you get this enormous chord which is straight out of Appalachian Spring by [Aaron] Copland,” says Arthur.

Arthur also plays in Sundog, in a piano/violin duet with Oli Langford, but as Penguin Cafe he has recorded three albums that are certainly cut from similar cloth to the parent group. He describes his own music as “more filmic”, and it feels more expansive, more opened out. So is it a homage to his fathers music, a continuation of a style, or is it all just in the genes?

“All three,” he replies. “I know when I am happy with a particular piece going in to a Penguin Cafe project, but there are some things that are just not right for it. It’s quite instinctive.”

Arthur is considering another tribute concert in 2018, as well as performing a mix of his and his father’s music with Penguin Cafe. He feels the activities are complementary, and he’s still coming up with new compositions.

“That has to be the point,” he says. “Every year or so I think about just stopping. But then I find something and think, ‘Oh, that would be really good, that would work.’ So we are being pulled forward rather than being pushed forward.”

Arthur’s music also demonstrates a familiar fascination with sonics.

“On the last Penguin Cafe album The Imperfect Sea, there’s a four to the floor, slightly house-y drum sound. It sounds just like a [Roland] 909. But actually there was a floorboard in the kitchen of my old house that had this lovely resonance if you tapped it with your finger and so we put a Neumann U87 [microphone] on a dishcloth on the floorboard and played that. So what I’m looking for is to find ways to recreate electronic sound organically and played on real instruments. And that rather sounds like fun.”

Union Cafe 20th Anniversary reissue is out now via Erased Tapes. See www.penguincafe.com for more.

How prog is former Ash guitarist Charlotte Hatherley?