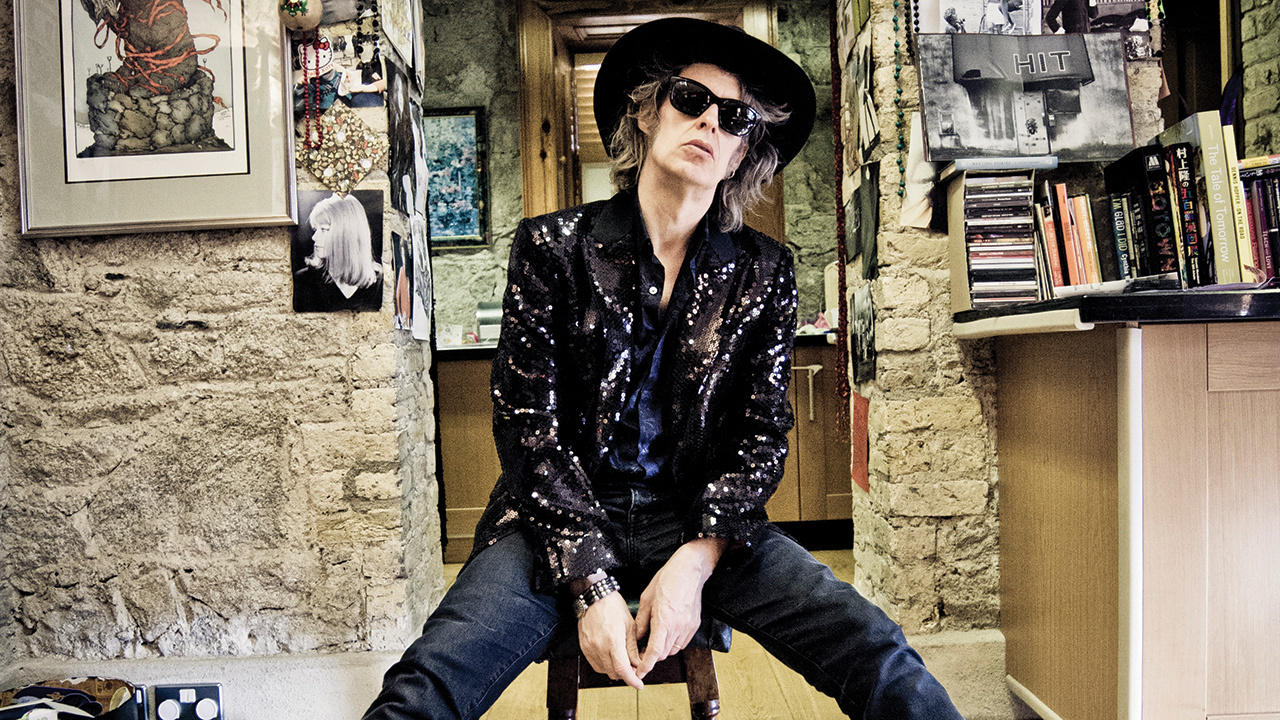

On this particular midsummer’s afternoon, Mike Scott, founder and sole permanent member of The Waterboys, is sat in a tucked-away café in his adopted home town of Dublin, recalling the specifics of his adolescent prog fixation.

“Around 1971, ’72, I was a big Pink Floyd fan,” he says, the lilt of his native Edinburgh still very much apparent in his voice. “My favourite Floyd album was Meddle. I was also a huge King Crimson fan and, I have to say, a teenage devotee of Blue Öyster Cult, and especially of their Spectres album.”

Not that Scott has ever made music that sounded remotely like the Floyd or King Crimson, much less the venerable American hard rockers. However, during 30-plus years both at the helm of The Waterboys and as a solo artist, he has followed his own path just as doggedly as, say, Roger Waters or Robert Fripp.

Now 58, Scott grew up in Edinburgh wanting to be a “heroic” footballer, before discovering Dylan, The Beatles and the Stones, and being moved to pick up a guitar. He passed through the typical litany of short-lived school bands and after an ill-starred year at the city’s university studying English Literature and Philosophy, he put together one that stuck: Another Pretty Face in 1978. They managed to get a record deal with Virgin, and Scott moved to London.

Another Pretty Face got as far as being on the cover of music weekly Sounds. Scott, though, restless even then, broke the band up and assembled The Waterboys to better realise his more vaulting aspirations. They became part of a kind of movement for the first five years of their existence, with Scott as one of its totemic figureheads. This was alongside fellow 80s trailblazers U2, Simple Minds and Big Country, under the banner of ‘The Big Music’, so called after the signature single from The Waterboys’ second album, 1984’s A Pagan Place.

The next year’s This Is the Sea was their watershed. Wide-eyed and rousing, it gave them a breakthrough hit, The Whole Of The Moon, which climbed into the UK Top 30 but stalled when Scott refused to lip-sync to get on Top Of The Pops. In any case, by then he was already looking ahead to a new dawn for the band.

Soon enough, he had jettisoned that line-up of The Waterboys and surrounded himself with another, decamping with this new group of musicians to a country house on the west coast of Ireland. There, Scott aimed to conjure music of a more pastoral, soulful bent, realised on the Fisherman’s Blues album of 1988. Now regarded as his masterpiece, at the time it baffled and shed a significant portion of his band’s audience.

“I grew up in the 60s and every time The Beatles or Dylan made an album, the frontier changed, because they moved it,” Scott says today. “In the 70s, it was Bowie and Roxy Music that went on changing their musical costume. I loved that. For me, that’s what one should do with music, and it’s a natural state. At the same time, I know it’s cost me a lot of fans. The music business also isn’t geared up for rapid change, but to reward repetition.”

Even so, and ever since, Scott has roved and roamed, his career increasingly coming to appear as an exercise in first and foremost satisfying his own inquisitiveness. He made another ‘raggle-taggle’ record with that incarnation of The Waterboys, Room To Roam, and after that a more conventional-sounding but near-concept set inspired by his nocturnal adventuring, Dream Harder, in 1993. For that one, he recruited a cast of top-class session musicians, but finding himself unable to gather a line-up to tour, ditched The Waterboys name and went off under his own instead.

In this venture, he set a course that was altogether opposite to the slickly produced Dream Harder, making a hushed, intimate record, Bring ’Em All In, at the Findhorn Foundation, an out-of-the-way communal retreat in the Scottish north-east.

“The right way to go solo is to do what George Michael did, which is go to America and make a record produced by the great Jerry Wexler,” says Scott. “George’s Careless Whisper had an amazing sax hook and all the best session musicians in the world, whereas I made a one-man acoustic record at a spiritual retreat in Scotland. It wasn’t so much about my wanting to escape, but I had got bored musically and always have been a bit of a seeker.

“In total it was a very tricky time for me, but to quote the song, I found what I was looking for at Findhorn and lived there for a couple of years. The experiences I had were wonderful, educational, and still serve me now on a daily basis. I learned to cut myself a bit of slack and to trust to instinct.”

Neither Bring ’Em All In or its more fleshed-out follow-up, Still Burning, managed to find more than a devoted cult following, and so, in 2000, Scott resurrected The Waterboys. His first steps back into the fold were faltering. He touted their comeback album, A Rock In The Weary Land, as a bold, new form, ‘Sonic Rock’, but really it sounded as if he had been listening to too much Radiohead. The record slipped by, unloved.

Subsequently, Scott recovered his bearings, without diluting his questing spirit. Over the last 14 years he has toured The Waterboys consistently and put out a clutch of admirable records, each one different to the other. Principal among these have been 2003’s mostly acoustic Universal Hall and, in 2011, An Appointment With Mr Yeats, on which Scott set a collection of poems by Ireland’s literary giant WB Yeats to music.

Given the scope of Scott’s vision, the latest Waterboys album, this year’s Out Of All This Blue, is perhaps the most inevitable, since it’s a sprawling double.

It’s a record that sounds as if it might have been beamed in from another, grander era. It was recorded mostly solo by Scott in his home studio, with long-time sideman Steve Wickham, Texan guitarist Zach Ernst and ace Muscle Shoals bassist David Hood among those to overdub their parts afterwards. Out Of All This Blue echoes most of all the boundless mood of the great white soul records of the early 70s made by Van Morrison and Joe Cocker in cahoots with Leon Russell – albeit that Scott also colours his palette with a battery of loops and samples, inspired by a shopping list of hip-hop records recommended to him by Ernst. This is most notable on one of the standout tracks, New York I Love You, which uses Lou Reed’s Sweet Jane riff as a jumping-off point into a heady collage of appropriated and found sounds.

“I love that Joe Cocker and Leon Russell Mad Dogs & Englishmen sound, and the movie is required viewing on The Waterboys tour bus,” Scott says. “In fact, we’re going to be touring this autumn with an expanded band of two drummers and girl singers. From 1967 to 1972, that’s a halcyon period of music for me, and one that I adore dipping into. You had all these great players like Jim Keltner and Nicky Hopkins shaping records by so many different artists.

“At the same time, I’ve used hip‑hop production values all over this record. I admire how someone like Kendrick Lamar will throw anything into his records and break up the rhythm to make a statement. They’re like audio movies in that sense, and I wanted to do something like that. Fortuitously, our drummer, Ralph Salmins, put me on to a website called producerloops.com that houses all these incredible collections of loops. I was like a kid in a toy shop.”

The majority of the album’s 34 songs are also reflective of Scott’s new-found domestic bliss. Last year, he married Japanese manga artist Megumi Igarashi, and he gives over the final quarter of Out Of All This Blue to rhapsodic love songs to his wife.

“Two thirds of the record is love songs,” he qualifies. “I’ve never written so many before, but then I’ve had such a romantic five or six years. Several were written during the courtship of my wife and some are drawn from other relationships that I’ve had.

“I did split it up conceptually and conceive of the whole as four sides of old vinyl. There’s something so evocative about the way vinyl breaks up an album and that you have these natural resting places.

“In the last few years I’ve also become a parent [he has a daughter with singer-actress Camille O’Sullivan and an eight-month-old son with Igarashi], and that’s diverting in the most wonderful way. It’s actually helped my music. My little girl is four and I’m constantly making up songs for her, which means my creative engine is running all the time. All of the songs on this new record were written in the last couple of years and in an atmosphere of constant song-making.”

Yet for all of this apparent contentment, Scott, one of our most undervalued craftsmen, still burns to be heard, and for his due recognition. While he doesn’t claim to have scaled the heights of a Dylan or a Leonard Cohen, he would back himself against any songwriter from his generation and the next. To his mind, with Out Of All This Blue, he’s laying down a gauntlet to his contemporaries. Or, as he expresses it, “Let them beat this.”

“I’ve always wanted to be the best,” he says. “It’s a healthy competitiveness, not toxic. I actually want other songwriters to do great work because it’s a bigger inspiration for me to be better and trump them.

“One of my favourite stories is about the great country singer Hank Williams. When he used to perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, between sets he would sit on the stairs to the stage door. As the other artists came up, Hank would peer at them from underneath his Stetson and say, ‘You can’t write ’em like old Hank, can ya?’ I like that. I’ll be sat there when U2, or Noel Gallagher, or Muse walk by, saying, ‘You can’t write ’em like old Mike, can ya?’”