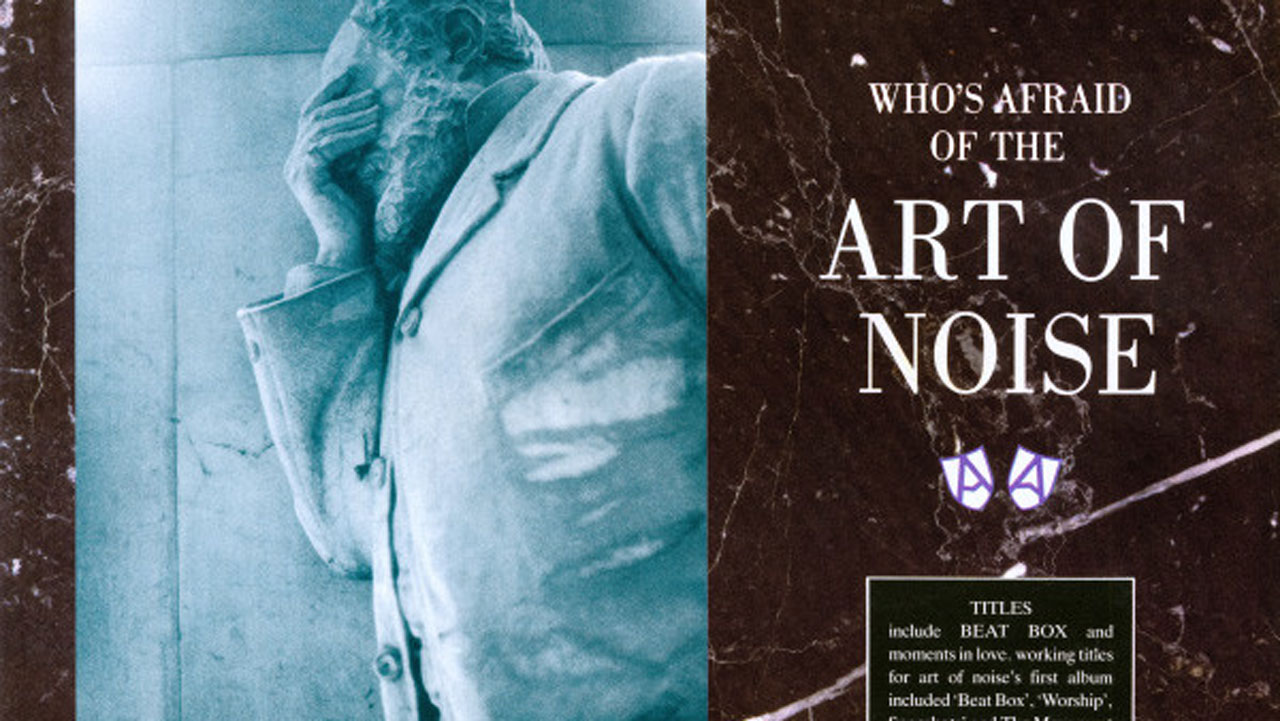

If there were awards given for high-concept messing about (which sadly there aren’t) then a clutch of them would have been scooped by the ZTT label around the years 1983-85. Records by Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Propaganda, Anne Pigalle and Grace Jones came complete with absurdly luxurious production, grandiose packaging and impenetrable sleeve notes, which were either infuriatingly pretentious or highly intriguing, depending on your point of view (and possibly how old you were).

The most glorious example of this nonsense came courtesy of The Art Of Noise, a studio collective which then featured Gary Langan, JJ Jeczalik, Anne Dudley and producer Trevor Horn. Langan was a sound engineer on Yes’ album 90125, and recalled how drummer Alan White’s kit was set up to create a sound that was “stupendous, like cannons going off”. Those thunderous taktak-booms formed the centrepiece of The Art Of Noise’s sound, around which everything else revolved.

The other crucial element of their soundworld was the Fairlight CMI Series synthesiser, which launched in 1979 for a cool £18,000, and heralded the arrival of sampling – pre-recorded sounds could be laid across a keyboard and played back as you wished. The sound of a stalled VW Golf restarting provided the band with the distinctive intro to their one hit from this album, Close (To The Edit). Referencing another Yes album title, this UK No.8 single featured a demented blues riff, big orchestral stabs nicked from Stravinsky’s Firebird and the famous vocal refrain ‘Hey!’, which was eventually sampled by The Prodigy on their own UK charttopping song, Firestarter.

But if Close (To The Edit) represented the listener-friendly side of The Art Of Noise, the album’s opening track, A Time For Fear (Who’s Afraid), was the diametric opposite. Pounding drums, industrial squeals and wartime speeches about military triumphs combined to create a blistering cacophony. The title track itself was similarly intense, a relentless, clattering beat underpinned by the insistent twang of a ruler on a wooden desk. (While it sounds conceptually frivolous, the results are unsettling.) And then there’s Moments In Love, famously played at Madonna’s 1985 wedding to actor Sean Penn: a sumptuous nine-bar sequence revolving and evolving for 10 minutes, but somehow never outstaying its welcome.

The Fairlight was an obscenely expensive toy. If you had access to one, your instinct might have been to record a dog barking and play a jolly tune. Plenty of people did just that. But The Art Of Noise, with consummate skill, used it judiciously to make something minimal but highly expressive.

To these ears, at least, the album sounds as fresh as it did nearly 40 years ago, and it amply demonstrates that The Art Of Noise were true prog artists: discarding all protocols, rejecting the zeitgeist, shunning the limelight and marching purposefully over previously untrodden musical ground.

This article originally appeared in Prog 135.