“Darling, he’s far too busy in the studio. That’s what happens when you get sick in Queen – you have to make the time up.”

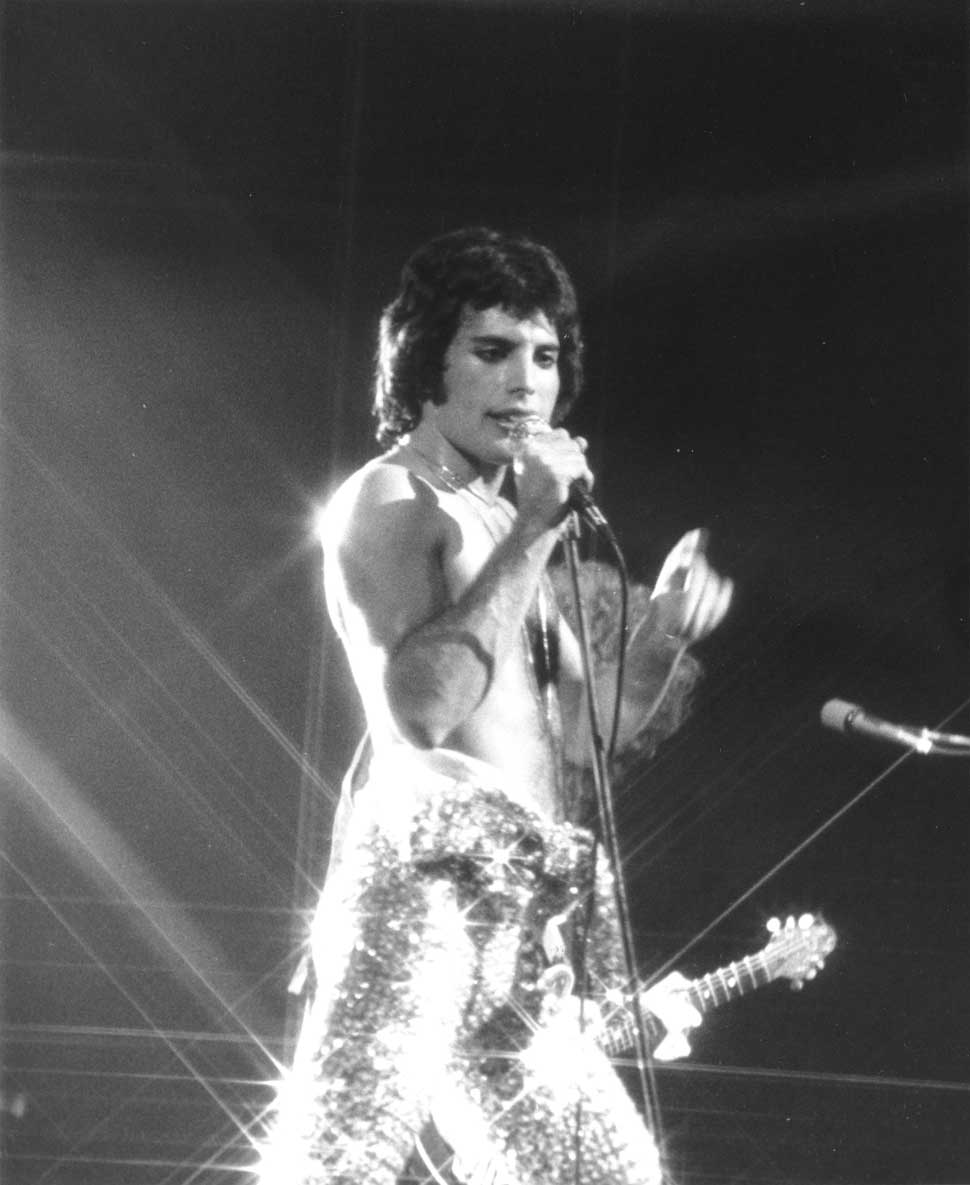

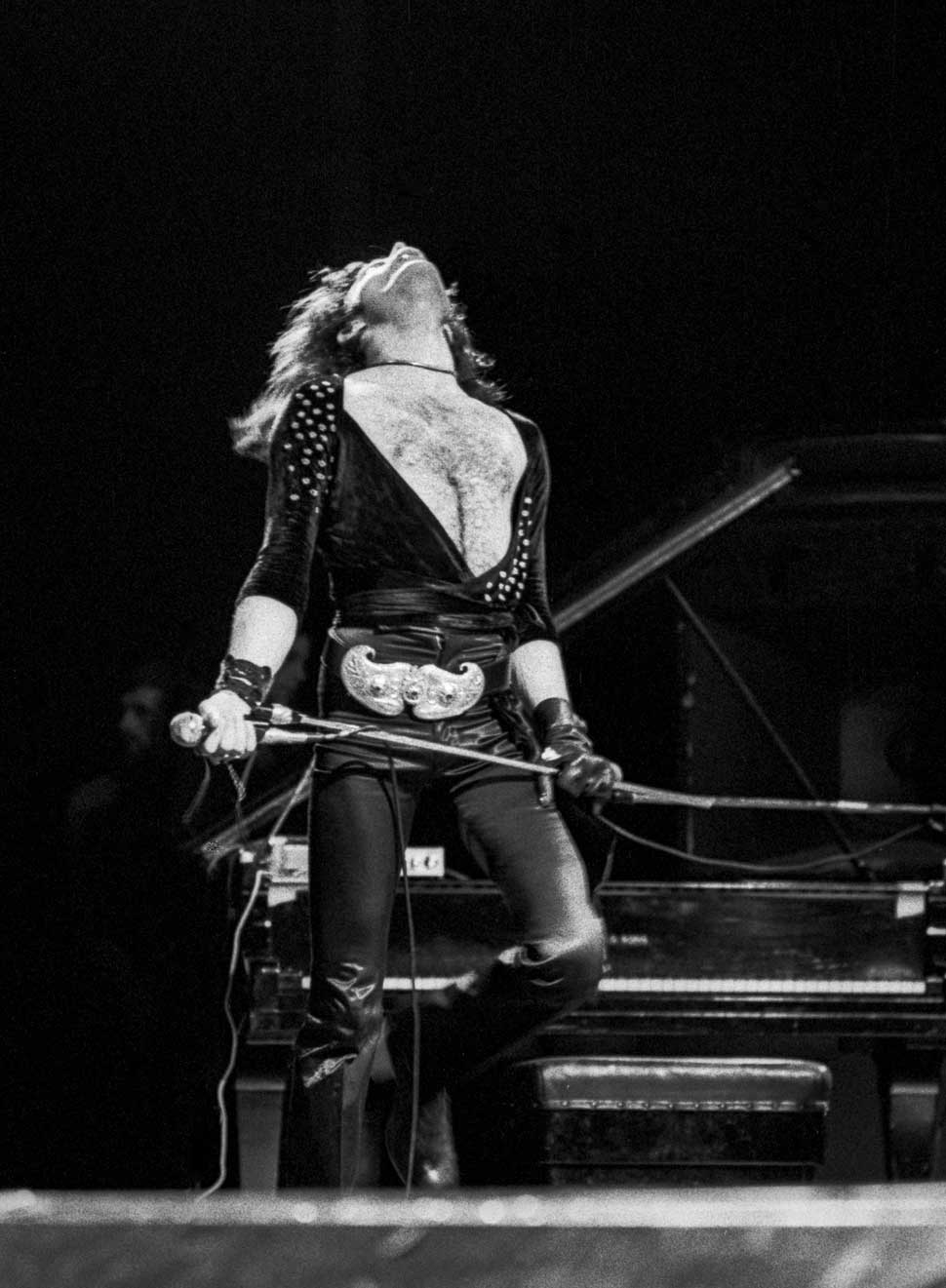

In the South London offices of his band’s PR company, a characteristically flamboyant Freddie Mercury is entertaining the press. It’s the autumn of 1974, and Queen have almost completed their third album, Sheer Heart Attack. Almost. For Mercury’s bandmate Brian May there’s still work to do. It’s just a few months since the guitarist was felled by a virulent bout of hepatitis mid-way through their debut US tour, and subsequently hospitalised for a second time with a stomach ulcer, forcing him to miss initial sessions for the album. May is currently holed up in the studio, finishing off his guitar parts, hence his absence today.

It’s typical of Queen’s ferocious drive that they haven’t let a pair of potentially fatal medical conditions get in the way of the job in hand. Their first two albums – 1973’s Queen and follow-up Queen II, released earlier in 1974 – set them up as a unique proposition: one part Zeppelin-esque rockers, one part glam dandies, one part fantastical Aubrey Beardsley illustration made flesh. Their music, along with their billowing silk blouses and Mercury’s outrageous, 1,000-watt personality, has earned them as much scorn as admiration. Both responses have only fuelled their ambitions.

But now those ambitions are coming into sharp focus. Like its predecessors, Sheer Heart Attack is the product of an intense work ethic that stems from a desire to be bigger, bolder and better than everyone else. It’s a watershed for the band: this album will lay the groundwork for future success.

There are solid economic factors, too. The album needs to be a success to boost their ever-decreasing finances. Their management, Trident Productions, have put them on a wage that barely pays the bills, while seeking a return on their hefty investments in recording and studio costs. Combined with May’s illness, it’s fair to say, there’s a lot riding on it.

“The whole group aimed for the top slot,” says Mercury. “We’re not going to be content with anything less. That’s what we’re striving for. It’s got to be there. I definitely know we’ve got it in the music, we’re original enough… and, now we’re proving it.”

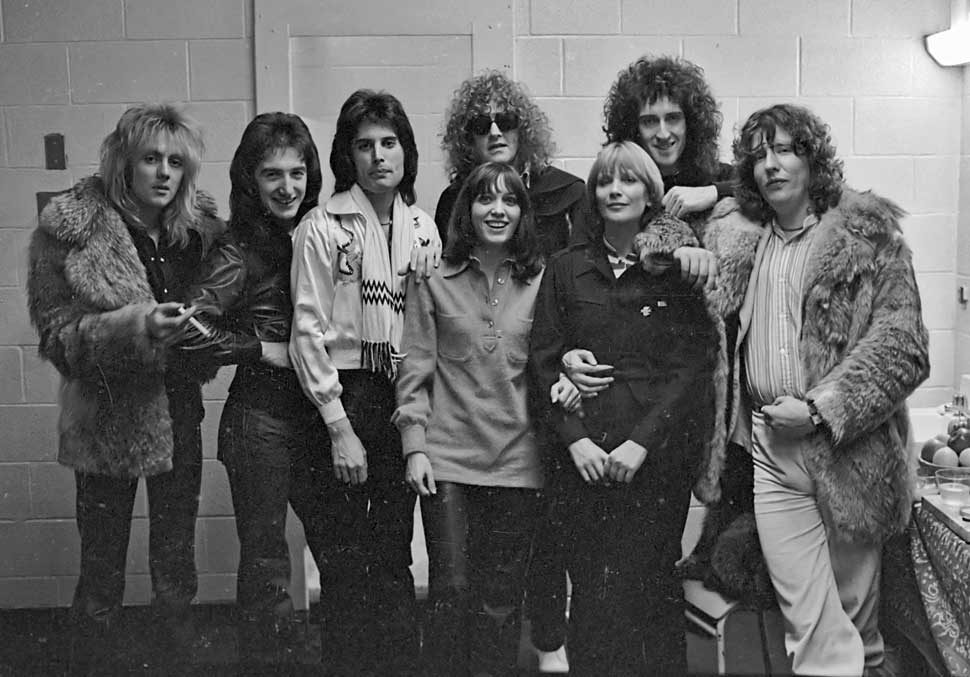

“I first met Queen in November 1973, when Mott The Hoople were rehearsing for their tour,” recalls Peter Hince, then a 19-year-old Mott roadie (and later one of the key members of Queen’s crew). “We were in Manticore Studios in Fulham, a converted cinema. It was freezing cold, everyone in scarves and coats. Then Queen came in in their dresses, their silks and satin. Even then, Fred was doing the whole thing, running up and down and doing his poses. My first thought was basically, ‘What a prat.’”

It wasn’t an uncommon reaction. Formed from the ashes of May and drummer Roger Taylor’s old band Smile in late 1970, Queen initially struggled to make a name for themselves. When eventually they did, they found themselves polarising opinion. While they had their admirers, they had also inadvertently become whipping boys for some sections of the British music press.

“We were just totally ignored for so long, and then completely slagged off by everyone,” Brian May acknowledged. “In a way, that was a very good start for us. There’s no kind of abuse that wasn’t thrown at us. It was only around the time of Sheer Heart Attack that it began to change. But we still got slagged off a fair bit even then.”

The opprobrium heaped on them may have hurt them individually, but it only strengthened their collective resolve. Where their first album owed a noticeable debt to Led Zeppelin, the follow-up raised the bar immeasurably. Divided between ‘Side White’ and ‘Side Black’ to reflect what Mercury called “the battle between good and evil”, it brought both operatic bombast and ballet-pumped daintiness to their heavy rock thunder – often in the same song.

“They planned everything in their heads,” says Gary Langan, then an assistant engineer at Sarm Studios in East London, who worked on two Sheer Heart Attack tracks. “Nothing was left to chance. That’s what separated them from other bands. You had to earn Freddie’s respect to get close to him. He used to scare the pants off me. The aura around that guy was astonishing.”

Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara, to Indian Parsi parents, on the island of Zanzibar, just off the eastern coast of mainland Africa. His formative years were spent at boarding school near Bombay, where he learned to play music and formed his first band, the Hectics. In 1964, when he was 17, civil war broke out in Zanzibar and the Bulsara family fled the island to settle in the altogether less dangerous environs of Feltham, Middlesex.

It was here, in the chrysalis of suburbia, that Farrokh Bulsara would ultimately transform himself into Freddie Mercury. The latter was an entirely self-created character, as camp and outrageous in public as he was shy and driven in private. By the time of Queen II, Farrokh Bulsara was a ghost known only to his family and closest friends; to everyone else he was Freddie Mercury.

Not that the rest of the band were content to exist in Mercury’s shadow. Three very distinct personalities, they each brought a different aspect to the band: May the studios intellectual, Taylor the louche rock’n’roller, Deacon the quiet man whose musical contribution would often be overlooked. It was a frequently combustible combination, albeit one with a shared vision.

“Do we row?” said Mercury in ’74. “Oh, my dear, we’re the bitchiest band on earth. We’re at each other’s throats. But if we didn’t disagree we’d just be ‘yes men’. And we do get the cream in the end.”

Fittingly, it would be Mott The Hoople who taught Queen how to be a rock’n’roll band. In October 1973, the foursome embarked on a 24-date UK tour with Ian Hunter’s survivors. Queen had released their debut album the previous July; the follow-up was already recorded, although it wouldn’t be released for another four months (a source of growing tension between band and management).

The two bands couldn’t have been more different. Mott were veterans of the rock’n’roll wars: they’d had their ups and downs, and had even split up before David Bowie threw them a lifeline in the shape of All The Young Dudes. They’d been there, done that, and rolled their eyes in wry resignation at the thought of it all. By contrast, Queen were young, hungry and at least striving for something approaching glamour. The rocks thrown their way hadn’t dented their drive for success in the slightest.

It quickly became apparent that Queen weren’t the usual makeweight support band. “They were quite pushy from day one,” says Peter Hince. “They demanded more space on stage, they were quite arrogant. They’d got this very clear idea of what they were going to do: ‘We’re gonna go for it.’ But you could see that they were already very good.”

For Queen, the tour was an invaluable lesson. They studiously watched the headliners. One of the songs in their own set was a prototype version of Stone Cold Crazy, a song that would later appear on Sheer Heart Attack.

“On tour as support to Mott, I was conscious that we were in the presence of something great,” said Brian May. “Something highly evolved, close to the centre of the spirit of rock’n’roll, something to breathe in and learn from.”

Typically, Freddie Mercury found playing second fiddle harder to swallow. “Being support is one of the most traumatic experiences of my life,” he would later pout.

The Mott tour finished with two shows at Hammersmith Odeon on December 13 and 14, but there was no rest for Queen. The next day they kicked off their own short tour at Leicester University. Shortly afterwards they flew to Australia to play their first show outside Europe; less happily, it ended with the band getting booed off by the roughneck audience.

By the time Queen II was released in March 1974, the band were finally matching their own self-belief. With a following wind behind them from the Top 10 success of Seven Seas Of Rhye, they kicked off their first proper UK headlining tour, starting in Blackpool, taking in such glamorous rock’n’roll destinations as Paignton, Canvey Island and Cromer, and peaking with a prestigious gig at London’s famed Rainbow Theatre.

There was a riot at a show in Stirling, when 500 audience members refused to leave the venue after the final encore, forcing the band to barricade themselves in the dressing room (the next night’s show in Birmingham was cancelled when the band were detained for questioning by the disgruntled Stirling police force).

For Freddie Mercury it was proof that Queen’s destiny was in their own hands. “You have to have confidence in this business,” said the singer. “It’s useless saying you don’t need it. If you start saying to yourself: ‘Maybe I’m not good enough. Maybe I’d better settle for second place,’ it’s no good. If you like the icing on the top, you’ve got to have confidence.”

While Queen’s star was rising in the UK, America was another matter. Barely known beyond a few Anglophile hipsters, they would need to start from scratch to build up anything resembling a Stateside following. Handily, their friends in Mott The Hoople were there to help them out again.

“We went out on tour with them. They were very nice people,” says Mott’s Ian Hunter. “Very intelligent. So we said, ‘Okay, do you want to come to America as well?’”

On April 16, Queen played their first US show, in Denver, Colorado as support to Mott. Remarkably, despite the band’s name and Mercury’s stagecraft, the more macho sections of the American audiences didn’t take against them.

“They were more like a normal group,” Hunter recalls. “They were playing rock songs, but with their own slant on it. They did say that they picked up a lot of their stagecraft from Mott, you know? You’ve got to pick it up from somewhere.”

This big-brother-little-brother dynamic was evident off stage, as was the support band’s desire to be successful. At one point the two bands found themselves staying in a set of apartments owned by Spartacus star Kirk Douglas.

“There was a bit of a do in my room,” says Ian Hunter, “and Fred’s marching up and down saying: ‘When are these silly bastards going to figure it out?’ Meaning the Americans. I said to him: ‘It’s a big country, you’ve got to go around three or four times before it happens. It’s not like England, where you can conquer it in a day!’ He was very, very impatient. It was hilarious.”

The Olympian levels of debauchery that became synonymous with Queen were a few years away, but there were still some memorable moments. Not least when the tour crossed paths with Bette Midler, then a brassy singer who’d made her name on New York’s gay bath-house circuit.

“She was doing a theatre in the same town as us,” Hunter remembers. “She latched onto Luther (Grovesnor, aka Mott guitarist Ariel Bender). And then we had Bette’s mob come back to the hotel with us. There was us, Queen, Bette and these seven-foot guys in feather head-dresses and what have you. Ha ha! It was so much fun.”

On May 7, Mott and Queen began a triumphant six-night residency at New York’s Uris Theater. But disaster struck the morning after the final show, when Brian May fell ill. The guitarist was diagnosed with hepatitis, possibly picked up from a dirty needle when they were inoculated before that ill-fated Australian show. Distraught, the band were forced to pull out of the tour, and May, against doctor’s orders, was flown home. Their plan to conquer America had been derailed. At least for the time being.

“To us it was out of the blue,” says Ian Hunter. “They were on the tour and then they’re not. Next thing we knew, they had the album out and it was doing extremely well.”

“I felt really bad at having let the group down at such an important place,” Brian May said in 1974. “But there was nothing to do about it. It was hepatitis, which you get sometimes when you’re emotionally run-down.”

Laid up in hospital after returning from America, May was feeling guilty and frustrated at inadvertently curtailing his band’s American ambitions. Understandably keen to rejoin his bandmates who had started work on their next album without him, he’d already begun writing while convalescing. One of the songs he was working on, Now I’m Here, reflected the disconnect between touring the US with Mott The Hoople and his living in a pokey bedsit in West London with his girlfriend. “It came out quite easily,” said the guitarist. “Where I’d been wrestling with it before without getting anywhere.”

It was a six weeks before May recovered from his bout of hepatitis. After being discharged he immediately rejoined the others in the studio. But something was wrong. May was constantly being sick, and he couldn’t eat anything. He was taken back to hospital, where doctors discovered that he had an undiagnosed stomach ulcer, which had been aggravated by the hepatitis.

“I was stuck in hospital for a few weeks, and they did some stuff to me which was like a miracle,” said May. “I thought I was dead. Being ill like that may even have been a good thing at the time, because although it was pretty hellish going through it, I felt glad to be alive and I became able to hold things in perspective more and not get so wound up and worried about them to make myself ill.”

By the time May returned to the sessions for the second time, work was properly under way on the new album. It was a strange experience for the guitarist, although not a negative one.

“It was very weird, because I was able to see the group from the outside, and was pretty excited by what I saw,” he later said. “We’d done a few things before I was ill, but when I came back they’d done a load more, including a couple of backing tracks of songs by Freddie which I hadn’t heard, like Flick Of The Wrist, which excited me and gave me a lot of inspiration to get back in there and do what I wanted to do.”

Sheer Heart Attack was recorded between July and October 1974. As with its two predecessors, the album was produced by Roy Thomas Baker, a larger-than-life character who could more than match Mercury in the charisma stakes.

“Every one of our musical and production frustrations came out on Queen II,” said Baker. “The idea for the third album was to get together and do some ‘simpler’ songs for a change; real little, short songs. And it was very successful on that level.”

Unlike Queen and Queen II, Sheer Heart Attack was conceived in the studio, albeit through necessity rather than by design. “Nobody knew we were going to be told we had two weeks to write Sheer Heart Attack,” said Mercury. “And we had to – it was the only thing we could do. Brian was in hospital.”

Despite the setback of the cancelled US tour, there was no doubt among the band that Sheer Heart Attack would take them to the next level. The black-and-white approach of Queen II had been reigned in, replaced by a kaleidoscopic range of sounds and styles. Leading this new approach was Killer Queen, an outrageously camp ditty that was closer to Noël Coward than to Robert Plant.

“That was the one song which was really out of the format that I usually write in,” said Mercury. “Usually the music comes first, but the words, and the sophisticated style that I wanted to put across in the song, came first.”

Many have claimed to be the inspiration behind Killer Queen, most notably Eric ‘Monster! Monster!’ Hall, the future football agent who then worked as Queen’s radio plugger. According to Mercury, the title chartacter was pure fantasy.

“No, I’d never really met a woman like that,” he explained after the album’s release. “I can dream up all kinds of things. That’s the kind of world I live in. It’s very flamboyant.”

If Killer Queen was the best-known song, it was hardly representative of the album, largely because the band didn’t chain themselves to one style. No band other than The Beatles had dared throw as many different styles into the mix with as much confidence. That state of affairs in Queen was helped by the fact that all four members pitched in with the writing.

A convalescing May delivered the rockers, including Now I’m Here and opener Brighton Rock (working titles: Bognor Ballad, Southend Sea Scout and Happy Little Fuck). Bookended by a picaresque tale of two seaside lovers sung in high and low registers by Mercury, it was a showcase for an extended May guitar solo dating back to Blag, a song by his old band Smile.

By contrast, Mercury threw in everything from waspish glam rock (Flick Of The Wrist, a reflection of their increasingly strained relationship with their management) to old-fashioned vaudeville (Bring Back Leroy Brown, complete with ukelele solo from May). Most prescient was In The Lap Of The Gods, a two-part, near-operatic epic that laid the groundwork for Bohemian Rhapsody the following year.

In this creative environment, the rhythm section also rocked up with material. Taylor, who had written a song for each of their previous albums, contributed Tenement Funster, a lachrymose salute to the rock’n’roll lifestyle, and an overlooked Queen gem. John Deacon chipped in with the slight but perfectly formed Misfire. The furious Stone Cold Crazy – an influence on the future members of Metallica, and hence a cornerstone of the thrash metal movement – was credited to all four members, even though it dated from Mercury’s pre-Queen band Wreckage.

For a band who were frequently mocked for being shallow, there were plenty of hidden depths, not least on Mercury’s delicate Lily Of The Valley. The singer’s sexuality was the subject of much debate in the press; apparent double-bluffs such as his famous proclamation that “I’m as gay as a daffodil, dear” deliberately clouded the issue. But while Mercury was still living with girlfriend Mary Austin, he reputedly told his closest friends that he was gay.

“Freddie’s stuff was so heavily cloaked, lyrically,” Brian May said in 1999. “But you could find out, just from little insights, that a lot of his private thoughts were in there, although a lot of the more meaningful stuff was not very accessible. Lily Of The Valley was utterly heartfelt. It’s about looking at his girlfriend and realising that his body needed to be somewhere else.”

All such personal distractions were kept out of the studio. “They worked 15 hour days,” says Gary Langan, who worked as tape operator on Now I’m Here and Brighton Rock. “When we finished work at Sarm, we’d meet them at a club called the Valbonne in Soho. That’s when they let their hair down.”

This drive for perfection ensured there was no fat on Sheer Heart Attack. Just two songs failed to make the final album. One was May’s imperious reworking of the national anthem, God Save The Queen, later resurrected for 1975’s A Night At The Opera. The other was the song that gave the album its title, the frantic, Taylor-penned Sheer Heart Attack. Little more than the bare bones of a song when they started, the drummer failed to finish it in time. They finally got around to recording it for 1977’s News Of The World album, underpinned with the sneering key lyric: ‘I feel so inar.. inar… inar inar…inarticulate’. The band in the next studio at the time? The Sex Pistols.

By the time Sheer Heart Attack was released on November 1, 1974, Killer Queen had already given Queen their first Top 3 hit. Now I’m Here followed a couple of months later, complete with touching nod to unofficial mentors Mott The Hoople (“It was nice,” recalls Ian Hunter, “but there was no money attached to it”). Between the two, Queen embarked on their first proper world tour, headlining. This time there were no illnesses or riots, though they were greeted by scenes approaching Beatlemania when they arrived in Japan in April 1975. The effort that went into Sheer Heart Attack had paid off.

Forty years on it stands as Queen’s most pivotal album. They had greater success later, but none of it would have be possible without the groundwork laid down here. “That was the album that showed the world what they were capable of,” says Gary Langan. “If that album hadn’t been as successful as it was, then something like A Night At The Opera probably wouldn’t have been accepted.”

Freddie Mercury put it more succinctly. “We were in a prolific stage and so much was happening with us, dear,” he said afterwards. “We felt the need for a change of sorts and, as ever, we felt able to go to extremes. As usual, we put ourselves under pressure. That’s just us.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #159.