"Sir, are you married?” asked Marianne, a pupil in Mr May’s mathematics class. “Sir, if you’re married, why doesn’t your wife iron your shirts?” she added, giggling.

Marianne Elliott-Said attended Stockwell Manor School in Brixton. It was spring 1972. Queen were making slow progress, so Brian May took a student teacher’s job while he worked on his PhD.

Marianne and her friends liked Mr May. He looked a bit like Mick Robertson from children’s TV show Magpie, and sometimes brought his guitar to class. He lived with his future wife, Chrissie, in a bedsit with limited space for ironing clothes.

“Brian was a very good teacher,” Marianne recalled, decades later. “But he used to come in with his long hair and holes in his shoes, and we used to tease him.” And so “Sir, are you married?” was often heard while May tried to teach some complex long division or geometry.

The joke ended in September that year when Queen’s management put the band members on £20-a-week wages and Mr May handed in his notice. One of the senior staff took him aside. ”You’ve got a proper job here, Brian,” he said incredulously. “You’re giving it up for a pop group?” But Mr May wouldn’t be swayed. Queen were hungry, desperate even, for success.

Today, Queen + Adam Lambert are still basking in the box-office glow of the film Bohemian Rhapsody and rehearsing for another US stadium tour. It’s easy to forget that Queen’s global conquest was a long time coming.

Their debut album turned 50 in July. Home to their first single, Keep Yourself Alive, it’s also the most-impatient-sounding album ever made. As one of their familiars once remarked: “Queen wanted the world… and wanted it no later than teatime on Friday.”

Queen began in June 1970. Before then, astrophysics student Brian May and trainee dentist and drummer Roger Taylor were two-thirds of Smile. The trio once opened for Jimi Hendrix but couldn’t catch a break. Their confidence was especially shaken after seeing Led Zeppelin.

“I felt sick,” May admitted, “because they were doing what we were trying to do, only a lot better.”

At the time, Zanzibar-born Farouk ‘Freddie’ Bulsara was a wannabe singer and art-student friend of Smile’s bassist Tim Staffell. Bulsara occasionally roadied for Smile, but rarely managed more than carrying a crash cymbal from the van to the stage. He preferred to dress like a rock star and tell Smile where they were going wrong.

Bulsara’s latest fashion accessory was a fluffy pompom attached to his wrist. “Very good, Brian,” he’d purr, while flicking the pompom in May’s direction. “But why don’t you present the show like this?” Pompom flick. “Why don’t you dress like this?” Pompom flick. “Why, Brian, why?”

After Tim Staffell quit Smile in the spring of 1970, their number-one critic made his move. “Freddie said: ‘You’re not giving up,’” recalled May. “He said: ‘I’m going to be your singer, and we’re going to do this and this and this…’” And with one more pompom flick, Freddie was in.

The new vocalist was full of ideas. A change of band name was the first. “‘Queen’ reflected the social world we were in at the time,” explained Roger Taylor, who had a side hustle with Freddie running a secondhand clothes stall in Kensington Market. “There was an eccentric crowd there, and a lot of them were gay or pretended to be. I didn’t like the name originally, and neither did Brian, but we got used to it.’

Soon after, Farrokh ‘Freddie’ Bulsara became Freddie Mercury. “Freddie had written a song called My Fairy King,” May explained. “And there’s a line in it that says: ‘Oh Mother Mercury what have you done to me?’, and he said: ‘I am going to become Mercury, as the mother in this song is my mother.’ We said: ‘Are you mad?’”

Mercury’s fashion sense and ambition were also ahead of his vocal ability. He’d previously sung with two amateur groups, but neither May nor Taylor had taken him seriously. “Fred sounded like a powerful bleating sheep,” said Taylor. “Not great. But he was a tribute to the idea that if you believe in something hard enough, you can make it happen. He believed in himself, and he believed in us.”

So began two years of baby steps and false starts. Queen regularly played May’s alma mater, Imperial College London, and opened for Wishbone Ash and Yes. It didn’t matter if they were performing to half-a-dozen students and a barmaid, Mercury already had the moves and the sawn-off mic stand seen years later at Live Aid. Off stage, he hustled any pop star who passed his and Taylor’s market stall.

“It freaked me out a bit,” recalled Slade’s bass guitarist Jim Lea. “Freddie said: ‘You’re Jim from Slade. I want to be famous like you.’ I said: ‘Look, mate, I’ve only come in here to buy something stupid to wear on Top Of The Pops.’ I felt sorry for him, but I gave him some advice. Queen hadn’t taken off then and I had no idea who he was.” Queen burned through three bass guitarists before finding unassuming electronics student John Deacon. His arrival in March 1971 was what they’d been waiting for.

Club DJ and A&R rep John Anthony had produced Smile’s only single, Step On Me. “What I saw in them was a sort of ‘Led Yes,’” Anthony told me, “because they had Yes’s harmonies and Zeppelin’s riffs. I was sure they’d do something, but not in that incarnation.”

Anthony had a production company with another up-and-coming producer, Roy Thomas Baker. Queen invited them to a showcase at Wembley’s De Lane Lea Studios, where they’d just cut a demo. The tape included Keep Yourself Alive, Liar, Jesus, Great King Rat and The Night Comes Down, all of which appeared later on Queen.

“Keep Yourself Alive sounded like a hit,” Anthony said. ‘I told them we were interested, but I was booked up producing other bands.’ However, Anthony and Baker had struck a deal with entrepreneurs Norman and Barry Sheffield, the sibling owners of Trident Studios in London. Trident’s reputation was forged when Paul McCartney played the studio’s Bechstein grand piano on Hey Jude. Now the Sheffields had extended the brand with management/production and filmmaking companies.

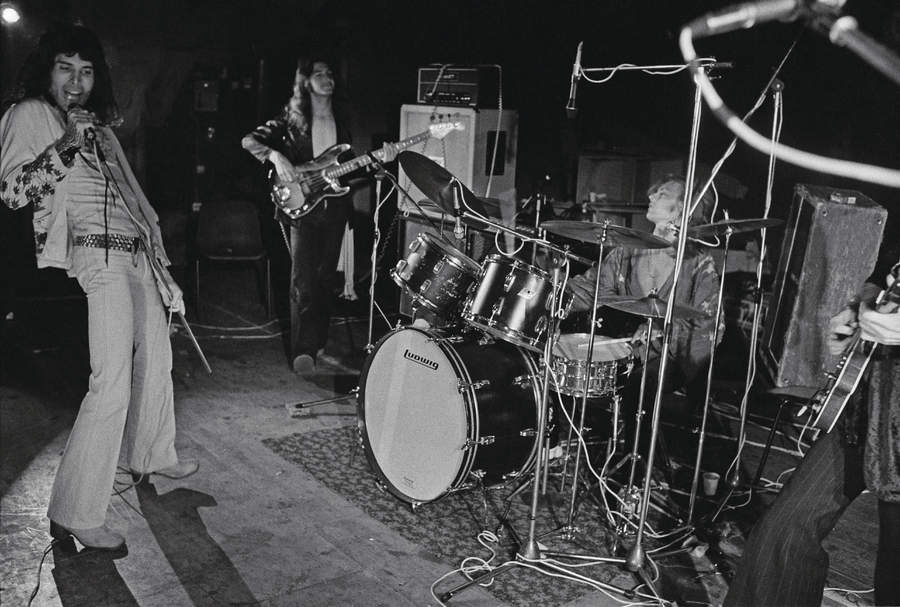

In March 1972, Anthony persuaded Barry Sheffield to attend Queen’s gig at a nursing college. The group included a couple of off-beat covers, and when May began playing the riff to Shirley Bassey’s Big Spender, Sheffield started laughing. “Right, that’s it,” he said. “We’re having them.” Queen signed with Trident and stopped playing gigs. “I told them to lie low,” said Anthony. “I wanted them to concentrate on getting their sound together.”

Over the next four years, Trident funded the recording of Queen’s albums and paid for new equipment, stage clothes and promo videos. But they also controlled Queen’s song publishing, the rights to their music and management. “Trident were wearing at least three hats,” said May. “It was not ethical, and they took incredible advantage.”

The best part of the deal was that Queen could use Trident Studios to make their first album. The caveat was they could only have it between 1am and 7am, “before the cleaners came in”, said May.

The Star café on Great Chapel Street now became a fixture in Queen’s nocturnal lives. The group would make four cups of coffee last, or, as a treat, head to The Ship pub in nearby Wardour Street. Soho bustled around them as Queen sat there, dressed to the nines, waiting to start work.

David Bowie was producing Lou Reed’s new album Transformer at Trident. While Queen were teaching maths or selling up-cycled fur coats, Bowie was having hits.

In July, Mercury and Taylor watched him premiere his Ziggy Stardust alter ego at Friars in Aylesbury. “I thought: ‘Bowie’s done it, he’s made his mark, and we’re still struggling to get a record out,’” said May.

Now Queen arrived at Trident and saw Bowie again. “Literally, coming down the stairs as we were going up,” Taylor recalled. Bowie later claimed he’d been asked to produce Queen’s first album.

Queen’s co-producers were John Anthony and Roy Thomas Baker. Mercury shared his vision with ‘Johnnypoos’, as he called him, early on. “Freddie showed me copies of Queen magazine [which later became fashion bible Harpers & Queen],” Anthony recalled. “Freddie said: ‘This is what we are about. But it’s not just the name, it’s the pictures, the articles, the whole thing.’ He had it all mapped out in his head.”

Then Anthony collapsed in the studio and was diagnosed with mononucleosis. “I went to Greece to recuperate,” he said. “So Roy took over.”

Roy Thomas Baker had helped engineer T.Rex’s Get It On (Bang A Gong) and Free’s Alright Now. But Queen clashed with him over the mic’ing of the amps and drums. “We wanted everything to sound like it was in-your-face,” said May. “We had this incredible fight to get the drums out of the booth and into the middle of the studio and to put the mics all around the room.”

However, Baker matched even Mercury for campness and grandiosity. He gushingly told Queen they were going to be “superstars”, but pushed them hard on take after take. “Not good enough, dearie, try again,” he’d declare. Baker’s catchphrase, “Dearie me”, was even mooted as an album title.

Baker had previous experience recording opera and classical music at Decca Records. “We never thought of Brian’s guitar as a raunchy instrument, as most guitarists do,’ he explained. “It was an orchestral instrument.”

May and Baker spent hours making the guitar sound like every instrument in the orchestra; hence ‘…and nobody played synthesiser’ in Queen’s sleevenotes.

As the night wore on, a bored Queen peered out of the window and watched the prostitutes and their clients below on St Anne’s Court. “It was a little bit of a diversion,” said Taylor. Listening to the album now, you can almost smell the collective coffee breath and see the band’s bleary eyes as the sun rose over Soho. No wonder Mr May arrived at school wearing a crumpled shirt.

Meanwhile, fellow Trident producer Robin Geoffrey Cable was recording a version of the Beach Boys’ hit I Can Hear Music next door. Cable overheard Mercury in full flight and asked if he’d sing on it.

Freddie agreed, and immediately began taking over: “Why not do this?” “Why not to do that?”… Before long, Taylor and May were also playing on the track. I Can Hear Music was released as a single a year later under the pseudonym Larry Lurex (a spoof of now-disgraced glam-rocker Gary Glitter). The single bombed, but gazumped Queen’s official debut by a fortnight.

The tracks on Queen captured the freneticism of the sessions. The magisterial ballad The Night Comes Down and a version of Smile’s Doing All Right were the only time the group paused for breath. In contrast, Keep Yourself Alive, Liar and Son And Daughter’s mishmash of castrato harmonies and symphonic guitars sound like a group in perpetual motion.

Queen even snuck in a fragment of their future hit Seven Seas Of Rhye at the end of side two. “Because Freddie had only written half the song then,” Taylor explained. Mercury’s Great King Rat and My Fairy King suggested a well-thumbed copy of The Hobbit, but apparently Mercury rarely read books. “Those songs are part of the zeitgeist,” explained Taylor. “Marc Bolan was an elf, so it was perfectly acceptable.”

Meanwhile, he described his debut Queen song, Modern Times Rock’n’Roll, as “a bit of a thrash”.

The album’s greatest anomaly, though, was Jesus. Freddie was baptised into the Zoroastrian faith, but plundered the Bible for ideas. The Tim Rice/Andrew Lloyd-Webber musical Jesus Christ Superstar had just opened, and Queen’s Jesus starts off like a show tune, and in the first verse has its titular hero healing lepers.

Other songs were considered but rejected. The underwhelming Mad The Swine was no loss. But Hangman, which sounded like Queen playing Black Sabbath’s Sweet Leaf, would have been a welcome addition.

The creative battle of wills between Queen and their producer Baker didn’t let up for a second. “Between Roy and I, we were fighting the whole time,” said May, “trying to find a place where we had the perfection but also the reality of performance and sound.”

Then John Anthony returned from Greece and insisted they remix the whole record. “Keep Yourself Alive sounded like it had been done at four in the morning, especially Roger’s drums,” he grumbled. And it probably had.

Working alongside them was 21-year-old assistant engineer Mike Stone. Stone impressed them all. His mix of Keep Yourself Alive was chosen for the album, and marked the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration with Queen. Finally, in January 1973, Trident ordered everybody to step away from the mixing desk.

The company now had to sell the album to a record company. To begin with, they were met with disinterest and even hostility. “Queen? Are these guys homos?” enquired one A&R man. It also didn’t help that Trident were flogging the record as part of a package, with albums by two other clients: ex-Rare Bird vocalist Mark Ashton, and Irish singer-songwriter Eugene Wallace.

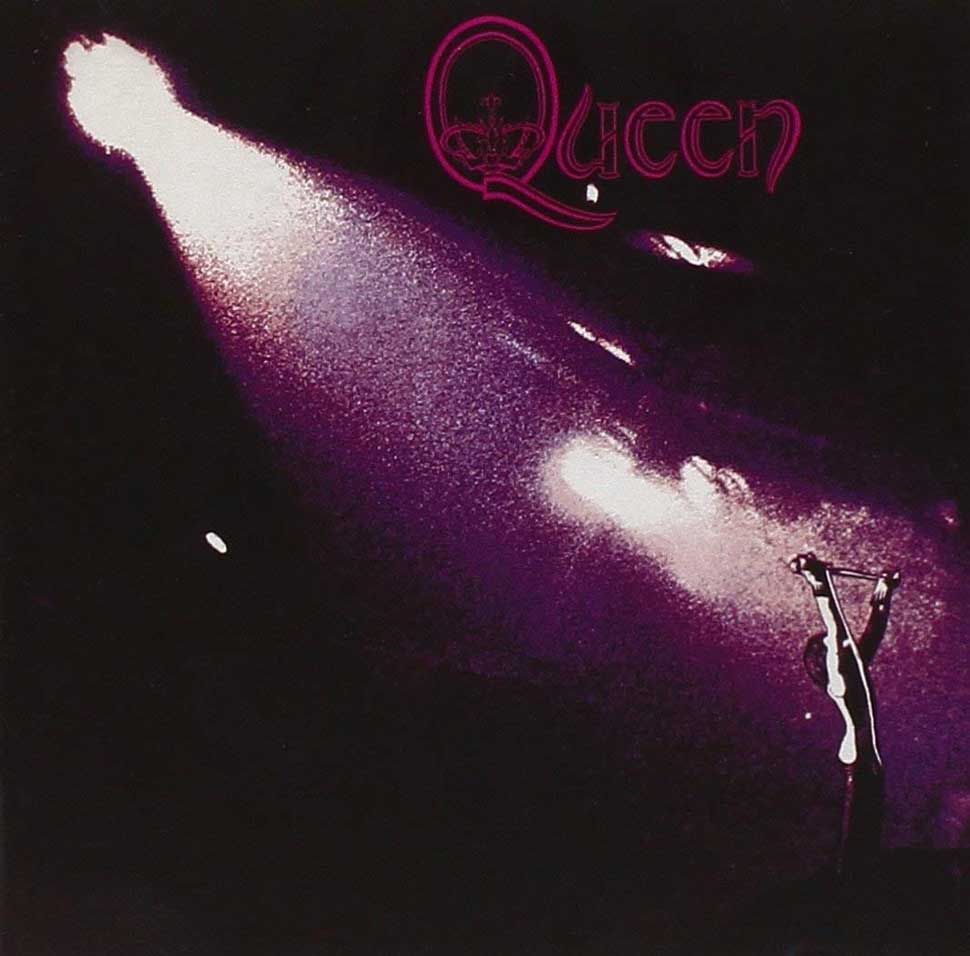

Eventually EMI Records said yes. Queen then railroaded the company’s art department into accepting their LP cover artwork: a Mercury-designed logo, and a photo of the singer “looking like a figurehead on the prow of an old ship,” said May. The back-cover montage included photos taken at a friend’s fancy-dress party: Freddie eating grapes, Roger as the Mad Hatter, and Brian wearing a homemade penguin mask complete with a working beak, which opened and closed when he spoke.

Taylor was listed in the credits by his full family name, Roger Meddows Taylor, and John Deacon became Deacon John. “To make him sound more interesting,” suggested one wag. “John Deacon never said a word,” recalled John Anthony. “Just stood at the back, going along with it all.”

Queen was released on July 13, 1973, more than a year after the group had started work on it. The sleeve-notes said as much: “…Representing, at last, something of what Queen’s music has been over the last three years…” Some reviews were positive – “Superb,” declared Rolling Stone. Others were less so – “A bucket of stale urine,” sniffed New Musical Express.

“We were into glam rock before Bowie,” a petulant May told Melody Maker. “But we’re worried we might have come too late.” Androgynous boys in bands were indeed on trend. Bowie had just released Aladdin Sane, and Roxy Music, with their leopard-print and feather boas, had just bagged a hit single and album. “So we don’t want people to think we’re jumping on their bandwagon,” May insisted.

Unfortunately, Queen stalled just outside the Top 30. That summer, London’s No.9 bus became the scene of many an earnest discussion. “If you ever get on a number nine, go upstairs to the front left, that’s where Freddie and I used to sit,” recalled May. “We used to get the bus up to Trident to ask why they weren’t doing anything with our record.”

The double-decker inched down Kensington Gore towards London’s West End. “God, I hope this band takes off,” Mercury fretted, staring down at the Royal Albert Hall. “I don’t know what I’m going to do if it doesn’t.”

Finally there was some good news. Mike Appleton, producer of the BBC TV’s flagship music programme The Old Grey Whistle Test, had received an unmarked promo of Queen. Appleton liked Keep Yourself Alive, but didn’t know who Queen were or how to contact them. So to accompany the track he used an animation based on a cartoon used in President Roosevelt’s election campaign, and broadcast it on the show. Queen were annoyed by the film, and then excited by the publicity. The group filmed a promo for the single, but Mercury had shaved his chest and hated the results. Once the hair had re-grown, they shot another.

Keep Yourself Alive was the first song May ever wrote for Queen. But it wasn’t a hit. “It didn’t get played on the radio,” he said. “We kept getting told: ‘It takes too long to happen, boys. It’s more than half a minute before you get to the first vocal…’”

The trouble was, Queen also considered their debut album a little passé, and were forging ahead with new ideas. In November they played a bunch of new songs while supporting Mott The Hoople on a UK tour.

Mott’s biggest cheerleader, David Bowie, had written their hit breakthrough hit All The Young Dudes, which turned them into pop stars. But Mott were a people’s band, with little time for highfalutin progressive rock. Neither they nor their crew had seen anything like Queen when they arrived for their first rehearsal. Everybody else at London’s Manticore Studios was dressed for a bleak British winter; Queen were in their satin stage clothes. According to one roadie, the general consensus was that Freddie was “a bit of awally”.

Trident paid £3,000 to get Queen on the tour. For a support act, they were undoubtedly precocious, hustling for more stage space and a drum riser. The headliners bristled at their demands, but Queen were too good to be dismissed. The groups travelled on the same bus, and quickly bonded.

“Brian was a very intelligent man,” said Mott’s lead vocalist Ian Hunter, “and Fred had so much confidence it was funny. I don’t think he even knew he was funny, which made it even funnier. In his head he was a star already.”

“We picked up a lot from Mott about stagecraft and connecting with an audience,” admitted May. “It was a true education. We took some of their tricks and started using them.”

“It was a true education. We took some of their tricks and started using them.” Mott’s signature song, All The Way From Memphis, included the line: ‘You look like a star, but you’re still on the dole.’ It could have been written about their support act. Queen were riding the No.9 bus with holes in their shoes, but behaved like they were headlining Madison Square Garden.

Everything Queen learned in the studio and on the road coalesced in time for their big break. In February 1974, David Bowie turned down Top Of The Pops because of prior commitments. Queen took his place and performed the full version of Seven Seas Of Rhye, even though it hadn’t yet been pressed as a single. They had taken the criticism of Keep Yourself Alive on board. “We thought: ‘Right, we’ll show ’em,’” said May. “On Seven Seas Of Rhye everything happens quickly.”

The song was a calling card for their next album, Queen II, and crammed cod-classical piano, screaming harmonies, Brian’s one-man London Symphony Orchestra, and lyrics about ‘the mighty Titan and his troubadours’ into a tight two minutes and 49 seconds.

“I never understood a word of it,” Roger Taylor admitted. “I don’t think Freddie did, really.”

None of the group owned a television, so they trooped down to an electrical goods shop in Kensington and watched their Top Of The Pops performance through the window. It was a watershed moment. “Finally, something was starting to happen,” said May. “We wanted to prove it to our friends and families, but mostly to ourselves.”

Seven Seas Of Rhye became Queen’s first Top 10 hit, and they never looked back. After winning a lengthy legal battle with Trident, their career soared with the hit single Bohemian Rhapsody and the albums A Night At The Opera and A Day At The Races. By the end of the 70s, Queen had equalled or overtaken the competition, including their nemesis David Bowie.

Fifty years ago, Queen’s debut album captured a young, restless group who, in the words of their future hit, wanted it all and wanted it now. But they weren’t the only ones dreaming of stardom. In 1974, Mr May’s former pupil Marianne Elliott-Said ran away from home to attend a music festival and travel around the country. She was living in a squat when she saw her old maths teacher wearing a cape and throwing shapes on Top Of The Pops. “I thought: ‘That looks good for a laugh,’” she said.

Marianne later changed her name to Poly Styrene, formed the punk group X-Ray Spex, and had two Top 20 hits. She died of cancer in 2011.

Some years earlier, Brian May was parking his car in Soho near the Radha-Krishna Temple, where Poly was a devotee. Ex-teacher and pupil spotted each other immediately. Mr May still had long hair, even if now his shirt was ironed and his shoes didn’t have any holes. May walked towards her and made the joke before she could. “Sir,” he said, grinning. “Are you married?”