Mick Fleetwood had only popped out for groceries. But a chance encounter with an old PR buddy at a shop near his home in Hollywood’s fashionable Laurel Canyon led to an invitation to check out a newly refurbished recording studio nearby. Eager to find somewhere to record Fleetwood Mac’s next album, he was duly taken to Sound City.

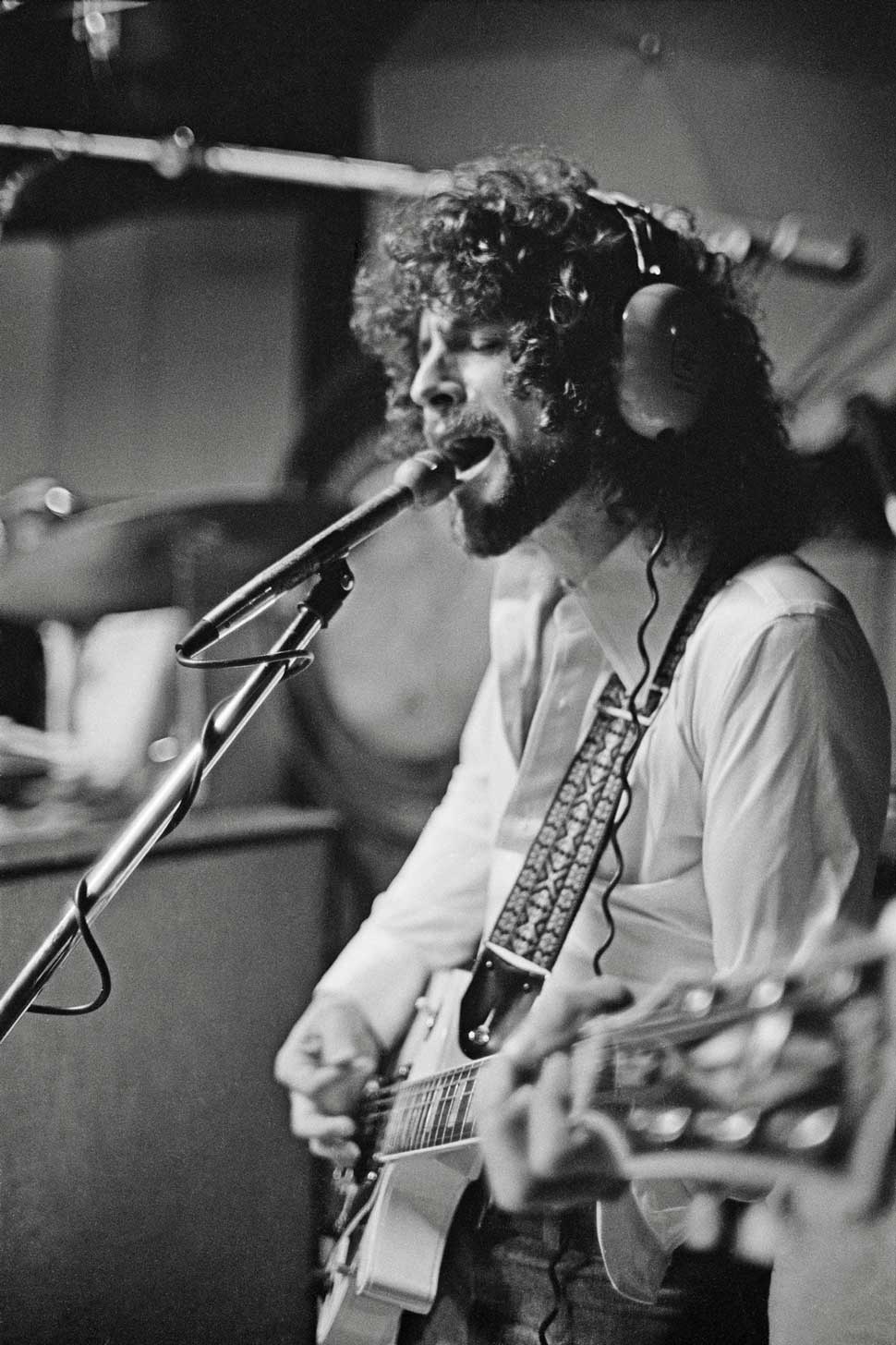

In-house engineer Keith Olsen was there to greet him. To demonstrate the studio’s sonic capabilities, Olsen played Fleetwood a track he’d produced for a local duo the previous year: Frozen Love. Its creators, the duo of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, had since been dropped by their label after the album, Buckingham Nicks, had tanked. Fleetwood, however, was smitten with the track.

Frozen Love was “seven enchanting minutes of vocal harmony and dynamic guitar”, he recalled in his 2014 memoir, Play On: Now, Then And Fleetwood Mac. “I loved what I heard and asked him to play more.”

A few weeks later, in December 1974, Fleetwood was rocked by the news that his band’s singer-guitarist, Bob Welch, was quitting. A combination of gruelling tour schedules and a disintegrating marriage had finally tipped him over the edge. Fleetwood Mac needed a replacement – fast. And their drummer knew exactly who to reach out to. He called Lindsey Buckingham and asked him to join. Buckingham was quick to stipulate that he and Nicks came as a package. This insistence impressed Mick Fleetwood.

“It was family first, it was loyal,” he recalled. “They were like-minded – they wrote together, lived together, loved together. They were very much what Fleetwood Mac was all about.”

So it was, in the first week of 1975, that Buckingham and Nicks formally became Fleetwood Mac’s latest members.

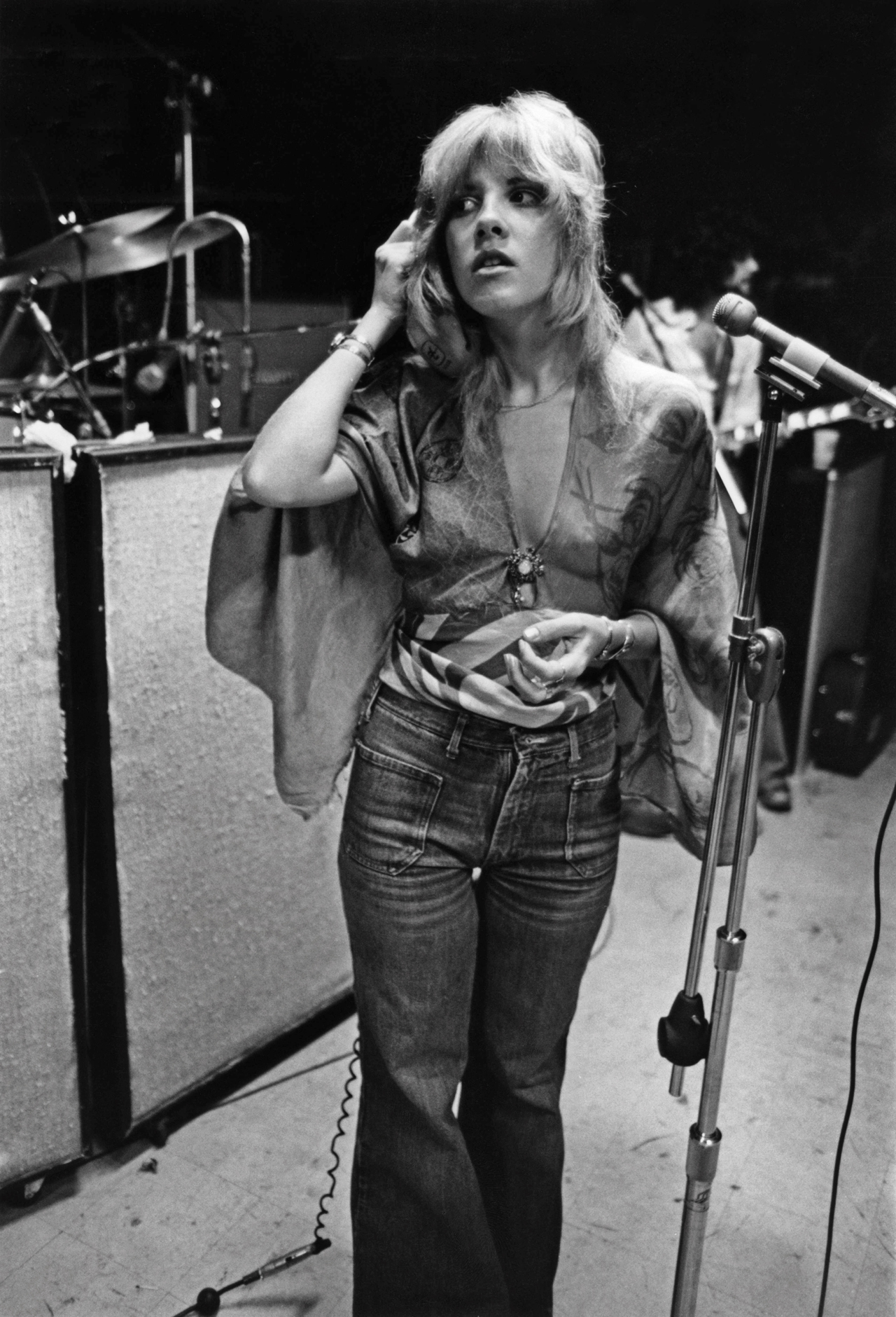

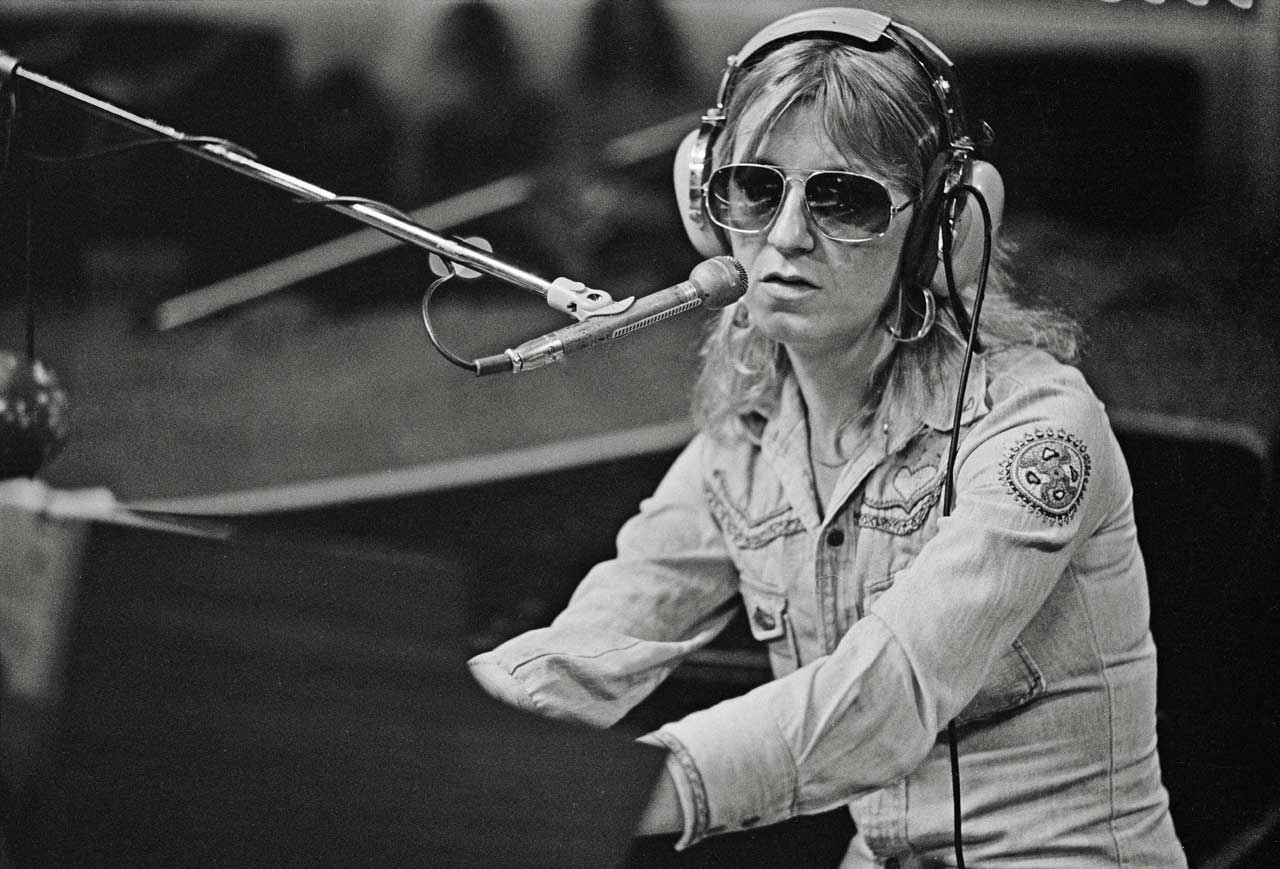

The arrival of the American couple signalled the end of a messy chapter in Fleetwood Mac’s career. Buckingham and Nicks seemed to offer a brighter future and, crucially, an expansion of the Fleetwood Mac sound. The band were now blessed with three first-rate singer-songwriters. Nicks’s pliant voice could shift in a heartbeat from a kittenish rasp to a wounded wail. Christine McVie brought a sturdier, though no less tractable, alto. Buckingham, meanwhile, brought a Cali-pop sensibility to his lead vocals and guitar work that finally unshackled the band from their blues-rock past.

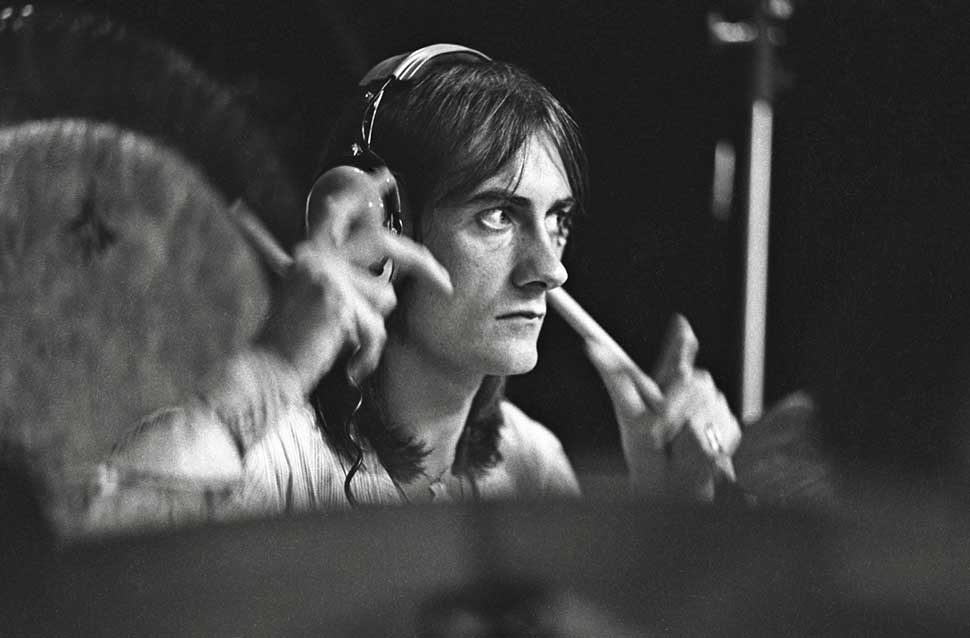

As they began work on a new album – the plainly titled Fleetwood Mac an indicator of this ground-zero dawn – the band suddenly sounded like a daunting commercial proposition. “It felt right. It was very quick,” Fleetwood later told the NME’s Chris Salewicz. “We all liked each other and that was it. We rehearsed for ten days and went in and made the album. It was a great sense of circumstance.”

By the end of February the record was done. Among the highlights were McVie’s soft-rocking Over My Head and Warm Ways, along with a couple of striking Nicks compositions: Landslide and Rhiannon, both of which dated from around the time of Buckingham Nicks. Landslide is a heartfelt commentary on the lot of the struggling artist, written in Aspen, Colorado after Nicks and Buckingham had been dropped by Polydor Records.

“I was looking out at the Rocky Mountains, pondering the avalanche of everything that had come crashing down on us,” she noted. Rhiannon was a sparkling example of the radio-friendly new Mac, governed by creamy harmonies, finger-picked guitar and John McVie’s sinuous bass groove. A supernatural tale, inspired by Mary Leader’s novel Triad, Nicks claimed to have written it at her piano in 10 minutes.

“I still have the cassette tape of when I was first writing it,” she told Classic Rock. “Lindsey came in and I said, ‘We have to go to a park and record the sound of birds rising.’ And he looked at me like I was crazy.”

All the more remarkable when you consider that Rhiannon became one of Fleetwood Mac’s most enduring songs, emblematic of their sound post-Peter Green. “There’s something to that song that touches people,” Nicks said in 1976. “I don’t know what it is, but I’m really glad it happened.”

Fleetwood Mac’s transition from blokey blues outcasts to mainstream superstars wasn’t quite the overnight success that revisionist history tends to depict.

Released in July ’75, the Fleetwood Mac album took some time to gain traction. The quintet toured the US for six months after completing it, the hard miles spent on the road eventually paying off when Over My Head made the US Billboard Top 20 early the following year. In June ’76, Rhiannon peaked at No.11 in the US, but it barely scraped into the Top 50 in the UK. The Mac had to wait until September before the album itself topped the US chart. Only Peter Frampton’s Frampton Comes Alive! outsold it that year.

Given the band’s previous crises – the loss and debilitation of Peter Green and Danny Kirwan, the lack of sales, a dwindling fan base and, of course, the sorry saga of the bogus line-up – it seemed as though it was all bouquets for Fleetwood Mac at last. But another messy narrative was already unfolding.

There had been tensions in the studio. John McVie, for example, had taken issue with Lindsey Buckingham’s sometimes dictatorial methods at Sound City, particularly his insistence that he teach the rhythm section their parts. McVie told him firmly: “The band you’re in is Fleetwood Mac. I’m the Mac. And I play the bass.”

This was nothing, however, compared to the relationship problems that were afoot. John and Christine McVie were on the brink of divorce, Fleetwood was going through the same thing, and it transpired that Buckingham and Nicks’s relationship was floundering too. Fleetwood had at first viewed them as “the perfect bohemian couple”, but the reality was very different. Fleetwood Mac would prove to be rock’s most tangled soap opera.

- Love That Burns: A Chronicle Of Fleetwood Mac Volume 1 1967-1974 - review

- Why Fleetwood Mac's Tusk is better than Rumours

- Fleetwood Mac duo release album documentary

- The best classic rock vinyl you need to own

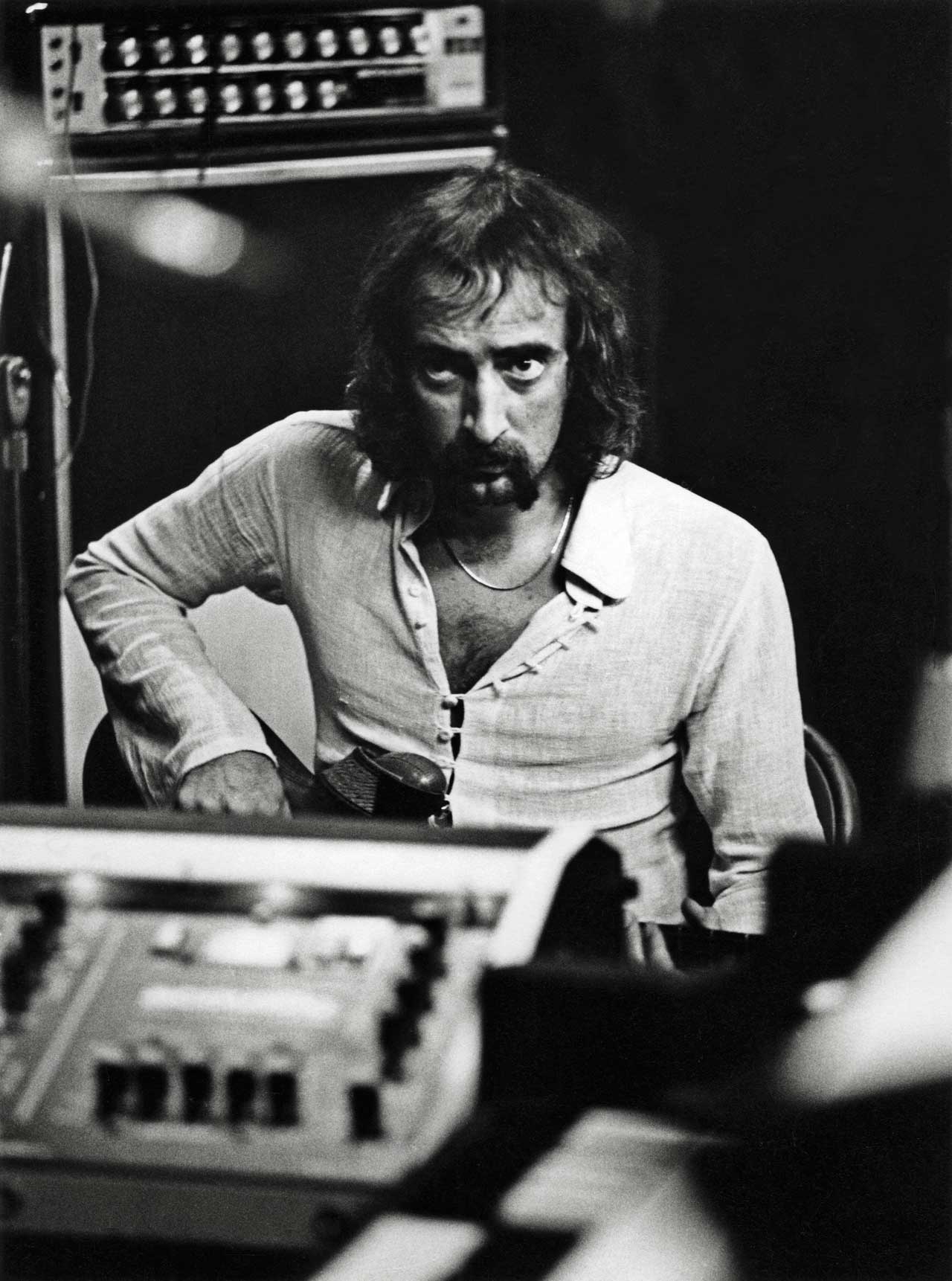

By the time they all began work on follow-up album Rumours in early 1976, the atmosphere within Fleetwood Mac was volatile. These interpersonal tensions were only heightened by the ubiquity of booze and drugs. Cocaine was plentiful in the studio.

Inside the Record Plant in Sausalito, co-producer Ken Caillat witnessed the creative toxicity first-hand. “It was like being trapped inside a tornado,” he told Classic Rock in 2007. “Some moments we were in the eye of the storm and all was calm, people were laughing and joking… A moment later everything changed and people were screaming at each other, breaking things; assistants were running for cover.”

According to Record Plant owner Chris Stone, speaking to Billboard in 1997: “The band would come in at seven at night, have a big feast, party till one or two in the morning, and then when they were so whacked-out they couldn’t do anything, they’d start recording.”

There were factions within factions: John McVie, Fleetwood and Buckingham were living in a house nearby, while Nicks and Christine McVie shared a small apartment.

The McVies had decided to limit their communication with one another to matters of music only. Yet even that detente was severely tested when Christine started seeing the band’s lighting director, Curry Grant. Distraught, John threw himself into the bottle. The situation wasn’t exactly sweetened when Christine wrote You Make Loving Fun as an ode to Grant.

“I don’t know if John ever really enjoyed the musical aspect of making the record,” Caillat remarked. “But he put his head down and delivered like a pro. Even while drinking, he never flubbed a line, not once.”

In contrast, Buckingham and Nicks dispensed with civility altogether. The only time they weren’t ranting at each other in the studio, by all accounts, was when it came time to do a take.

Talking to Classic Rock’s Max Bell in 2013, Fleetwood pondered aloud: “How did we survive making it with all these ex-lovers blowing up in each other’s faces? It was emotionally charged. We forced ourselves into a one-on-one, twenty-four-seven, pressing creative world. That’s a lot to ask when every time you look at someone your heart is in your mouth, or you’re feeling so hurt you just want to get a dagger and stick it in his or her back.”

It’s to Fleetwood Mac’s lasting credit that they were somehow able to unite all this fragmentation into a cohesive whole. Musically, Rumours builds on the driving AOR of its predecessor, adding richer blends, bigger harmonies and a near-perfect consistency of acoustic and electric textures.

The songs, unsurprisingly, are almost all about relationships. Don’t Stop was Christine McVie’s attempt to inject a little positivity into the band’s perilous emotional state; an infectious singalong that banished pessimism to the four winds: ‘Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow/Don’t stop, it’ll soon be here/It’ll be here better than before/Yesterday’s gone, yesterday’s gone.’

Another Christine McVie song, Oh Daddy, was supposedly written in honour of Mick Fleetwood’s temporary reunion with his wife, although conflicting stories say it was another song for Curry Grant.

Buckingham’s Second Hand News and Go Your Own Way both addressed the fallout from his failed relationship with Nicks. The former was a carefree rebound anthem about finding comfort in the arms of others. The latter carried a similarly upbeat tone, and stunning three-way harmonies that arrived on the back of a rhythm inspired by the Stones’ Street Fighting Man. Nicks was unhappy about some of Go Your Own Way’s lyrics, particularly ‘Packing up/Shacking up’s all you wanna do.’ “I very much resented him telling the world that ‘packing up, shacking up’ with different men was all I wanted to do,” she complained to Rolling Stone. “He knew it wasn’t true. It was just an angry thing that he said.” But Buckingham refused to amend them.

Among Nicks’s contributions was Gold Dust Woman, a document of excess, the title referring to cocaine. Dreams concerns itself with her split from Buckingham, advising her ex-lover to ‘listen carefully to the sound of your loneliness’ and pointing out that women will merely come and go. Even Nicks’s I Don’t Want To Know, written prior to her joining the band, was very much on theme.

Rumours took more than a year to complete, but the time – and pain – was justified. It was an instant success upon its release in February 1977, shooting to the top of the Billboard’s chart. Within 12 months it had sold nearly 10 million copies, made No.1 in the UK and won a Grammy. Alongside The Eagles’ Hotel California, it represented the commercial apex of West Coast soft rock during the 70s. It has gone on to achieve worldwide sales of more than 40 million. Mick Fleetwood has suggested that the romance of Rumours lies in its voyeurism.

The overwhelming success of Rumours only accelerated the band’s indulgent behaviour. Their new luxury lifestyle meant private jets, a fleet of limos and outrageous tour riders (according to Fleetwood, Nicks demanded a pink room with a white piano). Cocaine was bought in bulk. In a move that echoed Pink Floyd’s appropriation of a giant pig, Fleetwood commissioned a 60-foot penguin to float over the stage at their vast outdoor shows. “We were pleasantly out of control,” he said.

Fleetwood Mac may have conquered America (and half the world), but they did so despite themselves. Intra-band relations refused to run any smoother. Fleetwood and Nicks began a wild affair, Christine McVie became involved with Beach Boy Dennis Wilson and John McVie took solace on his boat in Marina Del Ray.

Buckingham, meanwhile, had immersed himself in his home studio, where he began plotting their next album. By his own admission it was an intense period that also saw him start to unravel. He was particularly mindful of being trapped by expectations in the wake of Rumours’ commercial performance. “We really were poised to make Rumours 2, and that could’ve been the beginning of kind of painting yourself into a corner in terms of living up to the labels that were being placed on you as a band,” he told Billboard in 2015.

Against Warner Bros’ wishes, the next album was envisaged as a double album. Buckingham had become fascinated by the edginess and innovation of post-punk and new wave, absorbing the music of Talking Heads, The Clash and others. Rumours hadn’t been without its avant-garde moments – jet phasers, Fleetwood hammering sheets of glass on Gold Dust Woman – but Buckingham wanted to take his musical experiments to a whole other level. He made obsessive home recordings, fiddling about with varying tape speeds, placing microphones in his bathroom and using a Kleenex box as percussion.

Fleetwood Mac spent a fortune doing up their own Studio D at Village Recorder in LA. Installing himself as executive producer, Buckingham presided over sessions that lasted well over a year, at a cost in excess of one million dollars, a then-record sum for a rock album. He also retained the services of regular co-producers Richard Dashut and Ken Caillat.

“He was a maniac,” Caillat said of Buckingham. “He’d tape microphones to the studio floor and get into a sort of push-up position to sing. Early on, he came in and he’d freaked out in the shower and cut off all his hair with nail scissors. He was stressed.”

A big wedge of the budget was spent the album’s title track, Tusk, semi-tribal gallop that evolved from a simple Buckingham riff that the band had been playing at sound-checks. They recorded the 112-piece USC Trojan Marching Band at LA’s Dodger Stadium to give the song some added oomph. If your ears are so attuned, you might also be able to make out the sound of Fleetwood slapping a leg of lamb with a spatula. Luckily for the band, Warner Bros slept easier when the song became a huge transatlantic hit in September 1979, a month before the album was released.

The Tusk album was a sometimes incongruous mix of tones and styles. Songs like the exquisite Sara and Sisters Of The Moon, both written by Nicks, felt like natural, very Mac-like extensions of Rumours. Others felt like separate individual visions, from Christine McVie’s downbeat Over And Over to a variety of Buckingham songs – the ruminative That’s All For Everyone, the folk-indebted Save Me A Place, the faintly psychedelic Not That Funny.

Compared to Rumours, Tusk was greeted like an expensive folly. Sales might have been highly respectable (four million copies worldwide), but the suits at Warner Bros deemed it a relative failure, citing Buckingham’s recklessness. Nevertheless, it was an artistic triumph and a global hit, a feat all the more impressive for being much pricier than a standard double LP.

For Buckingham, however, it represented something far more valuable at the end of a bust-to-boom decade that had threatened to turn Fleetwood Mac into just another commodity.

“Tusk was the most important album we made,” he told City Pages in 2011, “because it drew a line in the sand that, for me, defined the way I still think today. I was trying to pave some new territory for us.”