"We were nobodies but in that moment, it felt like we had a shot." How Slipknot overcame jealousy, substance abuse and trauma to become metal's most important band

25 years on from their self-titled debut, Slipknot look back at the years that helped them define 21st Century metal

For Slipknot, getting selected to play Ozzfest 1999 was a dream come true. Not only would the Des Moines nine-piece get to embark upon their first national tour in the company of some of metal’s biggest artists - Black Sabbath and Slayer among them - but the travelling summer caravan would present them with a priceless opportunity to promote their forthcoming debut album, scheduled for a late June release on Roadrunner Records, all across the country.

On the eve of the tour’s opening date in West Palm Beach, Florida, as their bandmates sat in the back lounge of a tour bus excitedly passing around a newly acquired copy of Metal Hammer issue 63 in which their forthcoming self-titled record was teased as “one of the most over-the-top and downright brutal recordings ever unleashed”, percussionist Shawn ‘Clown’ Crahan and drummer Joey Jordison could be found repeatedly sprinting across a hotel parking lot, competing in what Clown calls “40-yard dashes” to burn off excess energy, such was their anticipation and excitement. “We were so fucking ready to go,” he recalls today.

The reality of that summer would come to outstrip Slipknot’s expectations. Previously unknown outside their home state of Iowa, the masked collective were Ozzfest ’99’s undisputed buzz band. Their explosive 30-minute second stage sets were nothing short of a mindfuck for virgin audiences, their intense, nihilistic, nightmarish songs making even the futuristic ‘cyber-metal’ of second stage headliners Fear Factory appear tame by comparison.

Each day, after their set, The Nine would walk offstage, still clad in their uniform red boiler suits and masks, and join Roadrunner’s street team volunteers in handing out free two-song album sampler cassettes. In that pre-everything-on-the-internet era, their identities were unknown to all but those who knew them from back home in Iowa, but they’d spend hours chatting to wide-eyed fans, their Midwestern manners and warmth a jarring, disarming contrast to the grotesque freakshow masks that concealed their identities.

But Ozzfest ’99 would also serve as a crash course in music industry bullshit for Slipknot. Drifting around the backstage compounds, unmasked and unrecognised, Clown would observe musicians he admired treating fans like shit, and bad-mouthing fellow artists. Guitarist Jim Root, just six months into his tenure in the band, also vividly remembers rival bands “shit talking” the Iowans.

“They’d tell us directly to our faces, ‘You’re not going to last’ or ‘You’ll be lucky if you sell 6,000 records’,” he recalls. “It was kind of a mental headfuck, and it shows you how competitive it could be at that time.”

Soon, following complaints from representatives of other acts on the bill that Slipknot’s daily charm offensive was proving a distraction by drawing people away from their shows, they were ordered to stop distributing their album samplers. Out of respect for Sharon Osbourne, whom Clown remembers being “so supportive”, the band suppressed their anger at the pettiness of the directive, and dutifully toed the line.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But seeing daily deliveries of pallets of cassettes left unopened at the close of each night as the band exited their dressing room began to increasingly irk the percussionist. Finally, he’d had enough. “I said, ‘Screw this, I can’t let these tapes go to waste anymore’,” he says. “I thought, ‘We’re not gonna get kicked off the tour, and if I have to apologise later, I will.’”

That evening, Clown stationed his bandmates at various points around the site’s perimeter, directing them to pass out tapes to fans seeking to make an early exit during Black Sabbath’s headline set. This operation successfully concluded, he rode his BMX bike across the slowly emptying parking lots, in which homeward-bound vehicles queued bumper-to-bumper.

“And wherever I went, all I could hear was our tape being played on hundreds of car stereos,” he marvels. “Bro, my brain just melted. I was thinking, ‘Might all these people buy our album?’ It was unreal, just incredible. We were nobodies, anonymous and faceless, with no record out, but in that moment it felt like maybe we had a shot.

It’s early August 2024, and Clown is once more preparing to embark upon an American tour, just as he did 25 years ago. Named after the iconic Al Pacino sample that precedes Corey Taylor’s vocals on (sic), the Here Comes The Pain tour is a celebratory throwback to 1999, marking the 25th anniversary of Slipknot’s game-changing debut album. It’s routed to include stops at some of the outdoor ‘sheds’ the band first visited on Ozzfest ’99. This time around, however, when the tour concludes in Des Moines, Iowa, the band’s homecoming will be a Knotfest branded show, an indicator of just how far they’ve come.

“I want to say something before we start,” Clown says, after introductory pleasantries have been exchanged. “And it’s about Joey [Jordison, original drummer who died in 2021] and Paul [Gray, founding bassist who passed away in 2010]. I’m doing these 25-year anniversary interviews, and not a lot of human beings are asking me about them. You can’t talk about any of this without talking about them.

“They’re greatly missed, and every day that I go through this 25-year anniversary, I miss them more, but also appreciate, love, and just acknowledge who they were to all this. It’s very important for me to say that, because these are two gentlemen that should be talking to you, and they can’t.

“Joey and Paul… Oh my God, they wrote this shit man,” he says softly. “Number 1 and Number 2. The path changed for us after they passed, and we had to keep going, and take a new path, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t know where we came from, or ever forget what brought us here.” L

ong before he ever pulled on a Clown mask, Shawn Crahan was a respected ‘face’ on the Des Moines music scene. An intense, hard-working, somewhat intimidating character who took his responsibilities to his family, his local community and his furniture business seriously, music had always served as an outlet for his frustrations, irritations and darkest thoughts, ever since his discovery of punk and alternative music as a teenager.

“I used to think metal was just weird hair and tights, until Paul Gray introduced me to really righteous metal,” Clown says, recalling how artists such as Sepultura and Testament entered his life in the mid-90s. By then, he’d formed The Pale Ones with singer Anders Colsefni, mixing death metal riffs, industrial percussion, jazz, funk and art-rock. Shawn himself played drums, even though there were better drummers on the Des Moines scene. That scene was small but tight knit, with members flowing between bands.

In December 1995, Shawn and Anders, together with Body Pit bassist Paul Gray, Joey Jordison and Josh Brainard of thrashers Modifidious, plus The Pale Ones’ guitarist Donnie Steele, entered Des Moines’ SR Audio studio to record some songs together. These songs would emerge the following October as a demo album titled Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat.

The name of this new collective? Slipknot. Positive feedback for the release fired Shawn, Joey and Paul’s ambitions for their new band. Shawn and Joey would meet every night at the latter’s workplace, Sinclair petrol station, and obsessively plot their next moves. Paul dropped by regularly to play the pair his latest musical ideas.

“Paul was a genius and Joey was a genius,” Shawn insists. “And they wanted to change the world. Those were my dudes. There was a lot of fighting and a lot of tears, but it was all love. It was the three of us going crazy for our dream.”

That initial dream nearly imploded one stressful night in the summer of 1997, when Anders Colsefni left the studio after an argument about vocals. “I looked at Joey, and said, ‘There’s only one thing to do. Get Corey Taylor.’ And Joey just laughed, and said, ‘There is no fucking way Corey Taylor will join us, no fucking way.’”

Corey Taylor was the cocky, 23-year-old prettyboy frontman of Des Moines’ most popular rock band, Stone Sour. He was, by his own admission, both a “snotty fucking asshole” and “the best singer in town”. Shawn and Joey may have mockingly dubbed him ‘The King Of Des Moines’, but they also recognised that he shared their hunger and ambition to rise above their circumstances.

Corey was working in a sex shop, Adult Emporium, at the time. He was on a shift when Shawn, Joey and guitarist Mick Thomson (who’d joined in 1996, replacing Donnie Steele) approached him.

“He saw us coming in on the security camera, and he was a little freaked out, because when Joey and I were out together, people knew there was something going on,” Clown recalls. “I wrote, ‘Do you want to come to practice?’, as in, ‘Do you want to try out for the band?’, on a piece of paper, and I handed it to him. Corey looked at it, his eyes got really big, and he didn’t know what to say. And then I took the piece of paper, and I put it in my mouth: what I wanted to do was swallow it, but then I thought, ‘I don’t want to get lead poisoning or something stupid’, so I put it in my pocket. Then he said, ‘Yes’ and we left.”

Corey turned up at SR Audio for his audition later that week, performing Me Inside, with his own newly written lyrics. “When Corey went in, and he hit that chorus, we just knew, man,” Clown says. “Our imagination went to some other realm of dreaming. Here was the lost piece.”

“It was such a change from what I’d done before but it felt so right,” Corey told me in 2018. “I was at their very first show and I remember standing in the audience going, ‘I’m going to sing for these guys.’ A year later, it ended up coming true.”

The singer informed his bandmates in Stone Sour – who included Jim Root – that he was jumping ship. “It was a bitter blow,” says Jim today. “I’d seen Slipknot play once before, doing this slow, sludgy metal with barking lyrics, and I couldn’t see how he would fit in, I couldn’t wrap my brain around it, because Corey was really melodic. And then he played me Me Inside, and I was like, ‘OK, I get it.’ It was drastically different from the Slipknot that I’d seen, but now I understood why they wanted him, and why he made his decision. I probably would’ve done the same thing.”

Corey made his live debut with Slipknot on August 24, 1997, at Shawn Crahan’s new bar, the Safari Club. By this point, there were nine people onstage: Shawn, Paul, Joey, Corey, Mick, Josh Brainard, guitarist-turned-sampler Craig Jones, second percussionist Greg ‘Cuddles’ Welts, plus Corey’s predecessor, Anders Colsefni, who had been relegated to backing vocals (a position he wouldn’t hold for much longer).

Each band member already hid his identity behind a bespoke mask, and soon after they adopted a uniform of coveralls. “That’s when the numbers started coming up,” Corey later recalled. “We were like, ‘Fuck our names, fuck the bullshit. Let’s go by numbers.’”

Joey Jordison took on #1 and Paul Gray #2. Shawn adopted #6 and Corey himself became #8. The other members at the time had their own numbers: guitarists Josh Brainard and Mick Thomson were #4 and #7 respectively, Craig Jones was #5 and Greg Welts was #3. That anonymity would become a feature of the band - long after they released their debut album, few outside of their inner circle knew what they actually looked like.

“In this town, you’re basically a nobody,” Clown later explained to Metal Hammer. “You’re just like everybody else… this shadow of an entity that walks around faceless. So we kind of put the masks on because that’s what we felt like - we were no one, and we automatically didn’t care about our faces. We put the masks on as if to say, ‘You don’t care who we are, so we don’t care who we are.’”

That may have been the case then. But it wouldn’t be for much longer.

In January 1998, Ross Robinson received a phone call from his business manager, telling him to expect a CD demo from a new band from Des Moines, Iowa named Slipknot. Having worked on the first two Korn records, Limp Bizkit’s debut Three Dollar Bill, Y’All$ and Sepultura’s Roots, he was one of metal’s hottest producers. Such was his status that Roadrunner Records had recently gifted him his own imprint, I Am.

Contrary to popular belief, Ross wasn’t instantly blown away by the Slipknot demo, which included future classics Wait And Bleed and Spit It Out. “It didn’t resonate with me,” he says now, speaking to Hammer from a Los Angeles recording studio, where he’s working on a new project with Sid Wilson. However, he was a big believer in fate. Slipknot’s manager at the time had reached out separately to the only contact she had in LA, who – unbeknownst to her – happened to be Ross’s own manager. For the producer, it was an “insane” coincidence that was too big to ignore.

“I just had this feeling about this band,” he remembers. “I said to my manager, ‘We gotta go to Des Moines, now.’”

On February 2, 1998, without previously having exchanged a single word with anyone in the band, Ross arrived in Des Moines to meet Slipknot for the first time. The band had recently been augmented by DJ Sid Wilson, aka #0.

“We’d arranged to meet them at Sid’s parents’ house, and they were all waiting for me, unmasked, on the deck,” says Ross. “As we drove up, I saw them run off, like excited children, into the basement where they rehearsed. Then they put on their instruments, and, oh my God…”

Slipknot planned to perform for the producer to show him what they were about. It was a full-on show, with one exception: they weren’t wearing their masks.

“Without the masks, I could see their facial expressions,” he says. “All that insanity was fully visible. I was kind of bummed out knowing that they wore masks because they were so expressive without them.”

That evening, with Ross in attendance, Slipknot performed at a sold-out Safari Club. The gig was every bit as unhinged as the producer had imagined. “They rolled up from behind the crowd,” he recalls. “No one knew they were coming. Joey was on Mick’s shoulders, kicking people in the head, and it was so freaking cool.”

Ross had to finish existing recording commitments with Amen, Machine Head and, surreally, rapper Vanilla Ice. There were also the terms of their contract with Roadrunner to be ironed out – at the producer’s insistence, the label would not receive a share of the band’s publishing or merch sales. As a show of faith, Ross invited the still officially unsigned band to LA in September to begin pre-production on their debut album proper at Cole Rehearsal Studios.

“We decided to drive out as a band,” Clown says. “We had a truck pulling an overloaded three-ton trailer. We almost died in that thing several times. I remember our families making us all food for the journey. Sid’s family loaded us up with sausages and the coolest shit for snacks.”

They were so all-in on their dream that they even chose to stay at a hotel called Roadrunner. “That’s how geeked-out we were as a brotherhood and how badly we wanted to do what we’d come out to do,” says Clown.

Slipknot spent a week at Cole Rehearsal Studios – where they got to watch Kiss prepping for an upcoming tour – before moving to Indigo Ranch Studio in Malibu. Before Ross would permit the band to set up their gear in the studio, the producer asked Corey Taylor to share the stories behind his lyrics with his bandmates. The vocalist held nothing back, revealing painful memories of growing up without a father, of childhood sexual abuse, of his teenage addiction to speed and cocaine, of being left for dead in a dumpster following a drug overdose and his subsequent suicide attempts. No one said a word as the singer spoke. Ross was in awe of Corey’s candour. “You take all the drama and darkness and trauma out of his words,” he says now, “and you’re left with pure love.”

It wasn’t just the singer who impressed the producer. “Corey is a genius, but he was surrounded by amazing people. Paul was an incredible songwriter and a really unique riff writer. Joey was unleashing pure white hot fire, and Clown was holding the whole force together with his wild mind. I still don’t know how those four were able to find each other. It’s one of those mysteries of humankind.”

It was Ross’s job to capture the chaos and intensity of Slipknot’s live show. “We made that album straight edge,” he says. “There were no drugs, no alcohol, no cigarettes, no nothing, because they had no money. But they were on a fucking mission, and they were so ruthless and so raw and so real. When we started recording, the performances were rabid. It was just unleash, unleash, unleash.”

He pushed the band to their limits, and then some. He body-slammed the guitarists as they were tracking, bombarded Joey and Shawn with plant pots – whatever it took to jolt the musicians out of their comfort zones. Corey’s vocals were recorded in a booth plastered with dried vomit, animal faeces and Amen vocalist Casey Chaos’s blood. “It was unreal, man,” says Clown now, laughing. “We were insane. It was the best time ever.”

With recording almost done, the band returned to Des Moines to spend Christmas with their families. Over the holidays, Josh Brainard dropped a bombshell: he was quitting. When Slipknot returned to Indigo Ranch in February, former Stone Sour guitarist Jim Root was their new #4. Today, Jim recalls turning down the offer when Clown, Joey and Ross called him at home.

“I didn’t want to walk into a situation where somebody else had done all the heavy lifting, where I hadn’t put the work in,” he says. “But Clown was like, ‘Jim, we’ve all played in bands that supported your band, and you kind of laid the groundwork for us to do what we’re doing now.’”

During the final days at Indigo Ranch, Clown would often find himself staring at a piece of art created by one of the studio’s previous occupants. Before they’d finished recording their own debut album with Ross several years earlier, Korn had mocked up a home-made platinum disc using a piece of card from a pizza package. They had signed it, framed it and hung it on a wall with a note saying: ‘This is our platinum disc.’

“I thought it was so cool,” Shawn admits. “It was like, ‘Whether we sell a single record, this is our dream, this is how good this record is, this is what we deserve.’ Then one day I was finishing eating a $1 pizza from the local pizza place. It dawned on me that Korn had been eating those same $1 pizzas, too. My brain just melted, man. I was like, ‘OK, we’re gonna go platinum too, I know it.’”

May 27, 1999. I’m here to cover the opening date of Ozzfest at the Coral Sky Amphitheatre, West Palm Beach, Florida. It’s insanely hot and unimaginably humid, and, as I stand at the side of the stage, I’m soaked with sweat and in very real danger of collapsing with sunstroke. At which point nine masked men in matching red boiler suits walk out onto the festival’s second stage and all hell breaks loose.

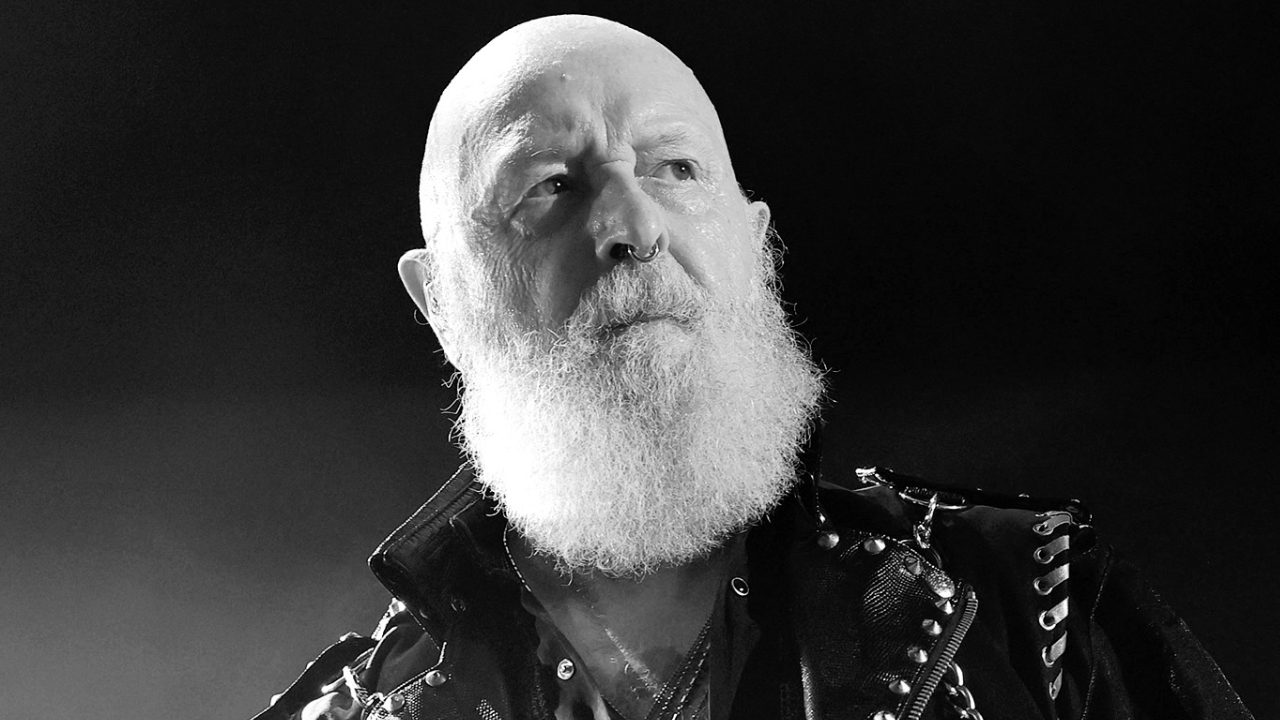

Slipknot are halfway up the bill on the second stage, but they’re already playing like they own the whole festival. Clown spends the set hitting beer kegs with a baseball bat as Craig Jones – sporting a black latex gimp mask with six-inch nails protruding from it – wrings white noise from a sampler. Elsewhere, percussionist Chris Fehn – who joined just before the band recorded their debut album, replacing Greg Welts as #3 – wanks the elongated nose of his unsettling Pinocchio-style mask, as gasmask-clad Sid Wilson repeatedly punches himself in the head. It’s the most chaotic, weird, terrifying, exhilarating, confusing, beautiful madness I and everyone else here has ever witnessed.

From that opening night, it was clear that nothing was going to stop Slipknot. “Ozzfest was mind-blowing,” says Jim Root. “We seemed to connect from day one. I remember after one of the shows, Joey was like, ‘We need to pull it together, we need to fucking be on our toes because this band’s fucking gonna blow up.’ At first, I didn’t have that intuition, but day by day you got the sense that we were picking up steam.”

Slipknot’s self-titled debut album was released on June 29, 1999, midway through that momentous Ozzfest run. It was an instant classic, a genuinely remarkable piece of outsider art that acted as a lightning rod for outsiders and outcasts. ‘Fuck it all! Fuck this world! Fuck everything that you stand for!’ Corey Taylor sings on Surfacing, nailing the band’s nihilistic appeal.

Metal Hammer’s review of the album drew comparisons with Korn, Ministry and underground noiseniks Fudge Tunnel, describing it as “the first frayed step on a journey into a hellish maze of torture and depravity”.

The album peaked at No.37 in the UK, and No.51 on the US Billboard 200, but its true impact was never going to be measured in purely commercial terms. I visited the band’s hometown of Des Moines in October 1999, and it was evident just how deeply it had connected with a fanbase the band had affectionately dubbed ‘Maggots’.

A signing session at a record store in the city drew more than a thousand fans, many wearing homemade masks and boiler suits, even more with lyrics tattooed on their arms and legs.

“We always remember where we came from and how hard it was to get here,” Joey told me. “Which is why we’ll kick 100% of your ass every night. If you keep a baboon in a cage for 24 years, the beast has got some shit to work out when it’s released.”

Slipknot were back in Des Moines as part of a tour that found them supporting Coal Chamber, who were being managed by Sharon Osbourne at the time. “We were fucking unhinged, and I think there were moves to kick us off the tour more than once,” says Jim. “But Sharon Osbourne would be like, ‘The reason you have people at these shows is because of that band. Shut your fucking mouths and play your shows.’ It was a very interesting time.”

Landmark moments came thick and fast. Slipknot played their first European show on December 13, 1999 at the London Astoria, a gig that’s since passed into legend. In March 2000, they made a chaotic appearance on primetime UK TV show TFI Friday, unleashing chaos on the early evening viewership. When they returned to the UK that August to play the Reading and Leeds festivals, one merchandise salesman in Leeds informed The Guardian that he had sold 14 t-shirts for headliners Oasis, and 2,500 Slipknot shirts. No metal band had embedded themselves in the public consciousness as quickly and deeply as Slipknot, not even Metallica or Korn.

“At the time, their success felt weirdly normal to me,” says Ross Robinson, “because I was having these hit records one after another. But the beauty of it was that it was so the opposite of what everybody else was doing. There were no blastbeats elsewhere on the charts, there were no extreme molten metal, destroyer riffs. Limp Bizkit and Korn were going showbiz, but Slipknot weren’t riding the Nookie train. That album was such a pure, perfect encapsulation of who they were. And that authenticity is what drew people in, and what you can still hear, 25 years on.”

The producer isn’t wrong when he says that. Slipknot’s meteor-sized impact would change both music and metal culture itself. The impact of their percussive barrage and the sheer intensity of the music as a whole brought extremity in from the margins, influencing everyone from Bring Me The Horizon to Suicide Silence and beyond, while their experimental streak paved the way for everyone from Deafheaven to Code Orange.

And then there’s the image: the masks and anonymity that seemed so freaky and new at the time are completely normal now. The current trend for bands hiding their faces and/or identities was seeded by Slipknot.

“That nine of us idiots from Iowa could have such an impact on the world, it’s really surreal,” Jim Root admits. “It’s still surreal. And it doesn’t occur to me until I talk to someone like you who points it out, because living in it, you can’t look at it objectively. We’re still us, and we just do what we do, and don’t think about it. Even now, really, we don’t understand how that affects anyone else. But it’s nice if people think we’ve made a difference to their lives.”

It’s October 1999, and Clown is in the living room of his suburban Des Moines home, his mask in his hand. He tells me that he slept badly the previous night because he was so excited about his band’s trajectory. He’d ended up watching James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster Titanic on TV.

“Joey told me the last half hour is so rad, so I watched it, and I’m not embarrassed to say, I got all fucked up, dude,” he said. “When the girl says goodbye to the guy and tells him she won’t forget him, it got to me. I got back into bed beside my wife, and I started thinking about my life. This is the craziest fucking dream I’d ever want.”

When I read this quote back to Clown today, one week before his band go on the road to celebrate the 25th anniversary of their debut album, there’s a brief pause as he absorbs his own words from a quarter of a century earlier.

“I got goosebumps listening to that,” he admits. “My whole body has got goosebumps. Man… what a journey. I’ve lost a child, I’ve lost my partners in crime - the two most important people who had most to do with that record are gone - but we’re still relevant, still making art, still believing, still hoping, still dreaming, still imagining. These 25 years have been insane. And I can’t tell you right now if it’s everything I wanted, because it’s not done yet, it just keeps morphing into more madness.

“It’s been hard. There’s been a lot of loss. We could have easily just said, ‘No more’ after Paul passed, easily just said, ‘Forget it’ after Joey died. There’s a lot that no one knows about that, but it’s no one’s business. We could have easily tossed in the towel. But I’m a fighter, and I don’t believe in giving up on believing. You know what? We need this band.

“Brother, the band will never be like that again. I can’t tell you how close we were then: we’re not that close anymore. People are gone. Craig’s out. Chris is out, Joey’s out, Paul’s out. The band is different. But, back then, there was nine guys that wanted to be in the same place, and we made it work. And we wound up here, and here is wonderful.”

Slipknot tour the UK from December 14. For the full list of dates, visit their official website.

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.

![Slipknot - Spit It Out [OFFICIAL VIDEO] [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/ZPUZwriSX4M/maxresdefault.jpg)