In 1977, the American glossy magazine New Times interviewed William Burroughs, the beat writer and junkie figurehead who had inspired many of the rock generation. Burroughs’s 1959 novel Naked Lunch had been required reading for aspiring beatniks, and featured a sex toy that, as every Steely Dan bore knows, the group named themselves after.

Burroughs had never heard Steely Dan’s music until his New Times interviewer turned up with their latest album, Katy Lied. After listening to the opening track, Black Friday, the king of the beats delivered his verdict: “They’re doing too many things at once,” Burroughs complained. “To write a best-seller you can’t have too much going on. You take The Godfather – the horse’s head? That’s great. But you can’t have a horse’s head on every page.”

The mid-70s was the era for rock groups “doing too many things at once”. Yet Steely Dan stood apart from all of them. The musical alter-ego of bookish New Yorkers Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, Steely Dan, with their broad musical palette, didn’t really fit in anywhere. Their music wasn’t progressive rock, and it wasn’t quite jazz, blues, pop or soul either, even if it contained elements of all that and more. Instead, Steely Dan marched to the beat of a different drum – one sometimes tapping out a 9⁄8 time signature.

Steely Dan are a great contradiction: a rock’n’roll group that aren’t really a group and don’t really like rock’n’roll, but have sold 50 million records to people who do. Of those records, Pretzel Logic is the one that unites full-blown addicts, weekend users and novices alike. It’s the Steely Dan album for people who don’t want a horse’s head on every page.

Pretzel Logic was released in February 1974, and included a soon-to-be US top-five single, Rikki Don’t Lose That Number. It was a collection of songs about drugs, time travel, hustlers, sex pests and jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker. Or maybe it wasn’t.

“Throughout our career as professional wiseguys, we used to put on the interviewers a bit for the entertainment of the readers,” Donald Fagen warned one critic, before claiming their interviews were rife with “hyperbole and outright lies”.

Then again, that’s all part of Pretzel Logic’s esoteric charm. Who the hell is the titular Rikki, and what’s so important about that number? It’s as if Steely Dan ask the questions, then sit back, smirking, as the listener searches for answers that might not even exist. However, that search often leads to the duo’s former alma mater, the Bard, which as any Steely Dan bore will tell you, was the inspiration for their 1973 song My Old School, and more besides.

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen met in 1967 at Bard College, a liberal arts academy in Annandale-on-Hudson, upstate New York. Fagen’s father was an accountant, his mother a one-time professional singer. Their son played piano and saxophone, and enrolled at the Bard to study English Literature. Becker, a fellow New Yorker two years Fagen’s junior, arrived to study music.

“One afternoon I walked over to the Red Balloon, a crummy little shack in the woods that served as an on-campus music club,” Fagen recalled. “I could hear someone playing electric blues guitar inside. But this wasn’t the trebly, surfadelic white-guy sound I was used to hearing.”

The guitarist, who Fagen though “sounded black”, turned out to be a very white Walter Becker.

Soon after, Becker joined Fagen in his college group. “Donald was the dean of the pick-up band,” Becker remembers. “There were about eight musicians on the whole campus, and most of them were pretty poor.” One such pick-up band, the Leather Canary, had fellow alumnus and future comic actor Chevy Chase as their drummer.

Becker and Fagen bonded over their love of science fiction, Lolita novelist Vladimir Nabokov and jazz. Fagen was shocked to find a kindred fan: “As far as I was concerned, Sonny Rollins was mine. John Coltrane was mine. Miles Davis was mine. No one else ever knew or cared.”

Former Bard students remember Becker and Fagen dressed all in black, chain smoking cigarettes and blasting out bebop through a pair of huge speakers Becker had won in a poker game.

But what also united the pair – and the Bard’s entire student body – was a shared sense of cynical humour. The lasting impression is of a college populated by long-haired, dope-smoking versions of The Catcher In The Rye’s Holden Caulfield. “[The Bard] was a very cool school,” recalled a former student, songwriter Terence Boylan. So much so that eye contact and even direct speech were frowned upon. “You sort of had to rub your knees and look at your feet when you talked” – a trait Steely Dan arguably carried over into their music.

After graduating in 1969, Fagen couldn’t wait to get back to the city; even the sound of chirping crickets irritated him. Becker was asked to leave (“I wasn’t doing any work”) and followed soon after. As well as My Old School, The Bard also gave them the idea for the song Barrytown, which later appeared on Pretzel Logic.

A suburban hamlet in nearby Duchess County, Barrytown was home to the Christian Brothers and a seminary for trainee priests. It was only a mile and a half from Bard, but to its hip student body it was like another country. ‘Look at what you wear, and the way you cut your hair/I can see by what you carry that you come from Barrytown…’ Fagen sang on the song, which suggested its composers already felt apart from the world around them.

Becker and Fagen spent the next three years living in Brooklyn and trying to peddle their songs to the publishers and producers at Manhattan’s famed Brill Building, from which had previously flowed a raft of popular music classics written by songwriters including Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Burt Bacharach and Hal David and Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. By now the two jazz snobs had overcome their earlier aversion to rock’n’roll. They liked Bob Dylan for his lyrics, The Beatles for their tunes and the Rolling Stones for selling black blues back to America – Fagen thought that was hilarious. But their own compositions were quite different from anything by those artists. “They were bizarre, depressing tunes,” Becker admitted, while Fagen said “no one wanted to hear them”.

No one, that is, except Kenny Vance, founder of the soul group Jay And The Americans, who’d had a string of hits in the 60s. Vance heard something in Becker and Fagen’s oddball, plangent ballads. He offered to manage the duo, and hired them as backing musicians and arrangers for his band, which gave them a chance to earn some money and gain valuable touring experience.

Back at the Brill Building, Vance tried to convince established artists to record their songs. Becker and Fagen even pitched Charlie Freak (later the penultimate track on Pretzel Logic) to Barbra Streisand’s producer. It included vaguely ambiguous lyrics about a drug deal and a fatal overdose (‘Poor kid, he overdid’), but the producer’s reaction was less ambiguous: “Kenny, what are you, crazy? You gotta be out of your fucking mind!” as Vance told Steely Dan biographer Dave Di Martino.

The meeting wasn’t entirely a waste of time, however. Streisand later recorded one of the Becker and Fagen’s compositions, I Mean To Shine. “But it was altered beyond the point where we would have to take responsibility for it,” said Becker.

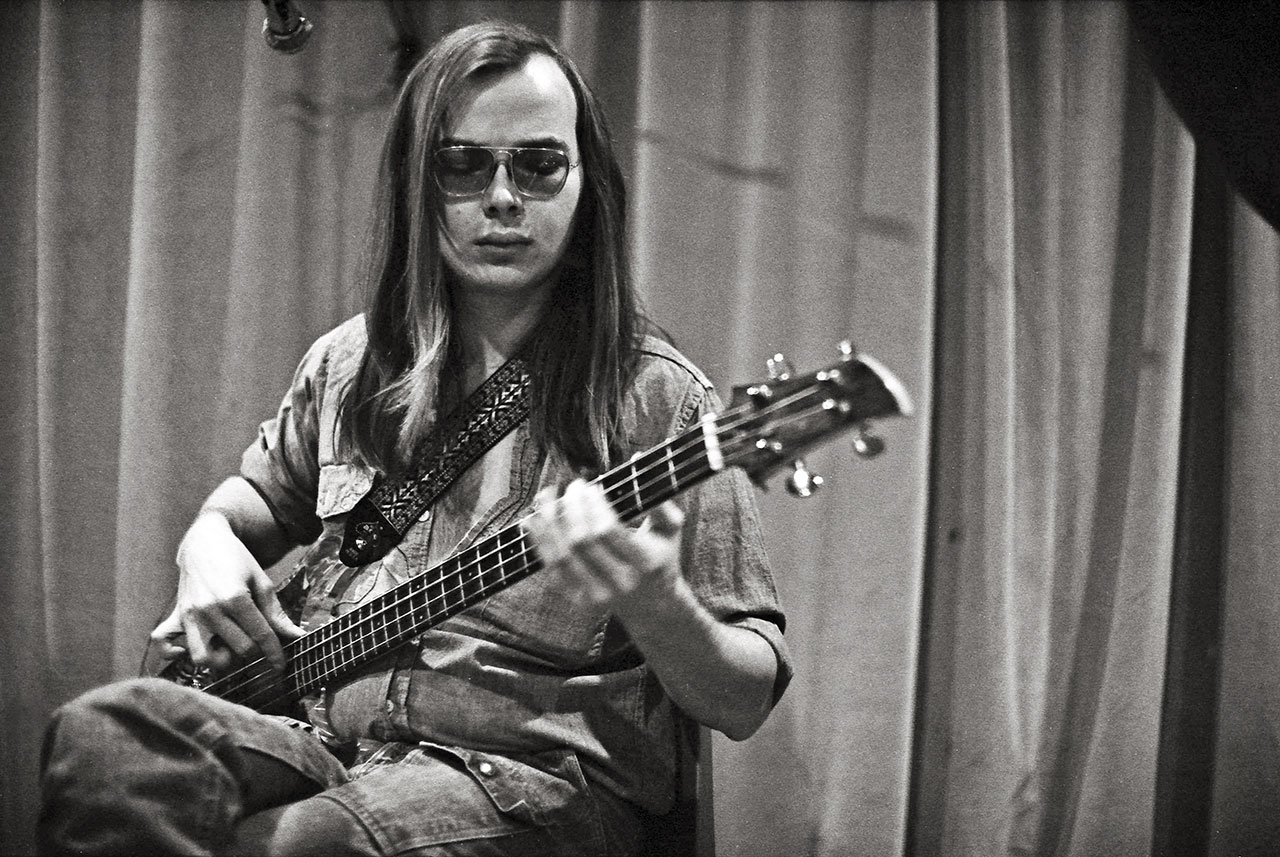

The catalyst for Steely Dan was an ad placed in alternative New York newspaper the Village Voice by guitarist Denny Dias in the summer of 1970: “Looking for keyboardist and bassist. Must have jazz chops! Assholes need not apply.” Becker and Fagen joined Dias’s group, but refused to play their Top 40 repertoire. Which alienated everyone, until only Dias remained.

In 1971, Becker and Fagen made their recording debut, with Denny Dias, on a Kenny Vance film You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It Or You’ll Lose That Beat. The film tanked, but you can hear the roots of Steely Dan in the duo’s unremarkable soundtrack.

By now their collection of unloved demos included four songs that would later be included on Pretzel Logic: Barrytown, Charlie Freak, Parker’s Band and Let George In, the latter eventually morphing into the album’s title track.

The big break finally came when Vance’s associate, Gary Katz, took a job as a staff producer at ABC Records in Los Angeles. Ordered to find some new talent, he called Becker and Fagen. The pair headed west.

Like Kenny Vance, Katz was convinced the odd couple had something, although nobody else agreed. “But when our job as staff songwriters at ABC failed spectacularly, the boss gave us a budget to record our own album,” said Fagen.

Denny Dias joined them in Los Angeles, where they brought in second guitarist Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter, drummer Jim Hodder and vocalist David Palmer, creating the first Steely Dan line-up.

Their debut album, Can’t Buy A Thrill, was recorded quickly at Village Recorders Studios in Santa Monica and released in November 1972. Palmer sang lead vocals on three tracks on the record, because Fagen didn’t like the sound of his own voice. But the singles from it, Do It Again and Reelin’ In The Years, with Fagen on lead vocals, raced up the Billboard chart, helping take the album to No.17.

Can’t Buy A Thrill was pop music reimagined by a pair of literate, jazz-loving wise-asses, its cryptic lyrics and odd chord changes suggesting a certain detachment – like they didn’t quite buy into the myth of rock’n’roll.

“We think these are very funny songs that we’re writing,” said Fagen. “And when we’re writing them we really do have a grand old time yukking it up about the lyrics.”

Having bagged an unexpected hit with Can’t Buy A Thrill, ABC Records pushed Steely Dan back into the studio in early 1973. But by then vocalist David Palmer was gone, after producer Gary Katz finally convinced Fagen that his peculiar nasal voice was the true sound of Steely Dan.

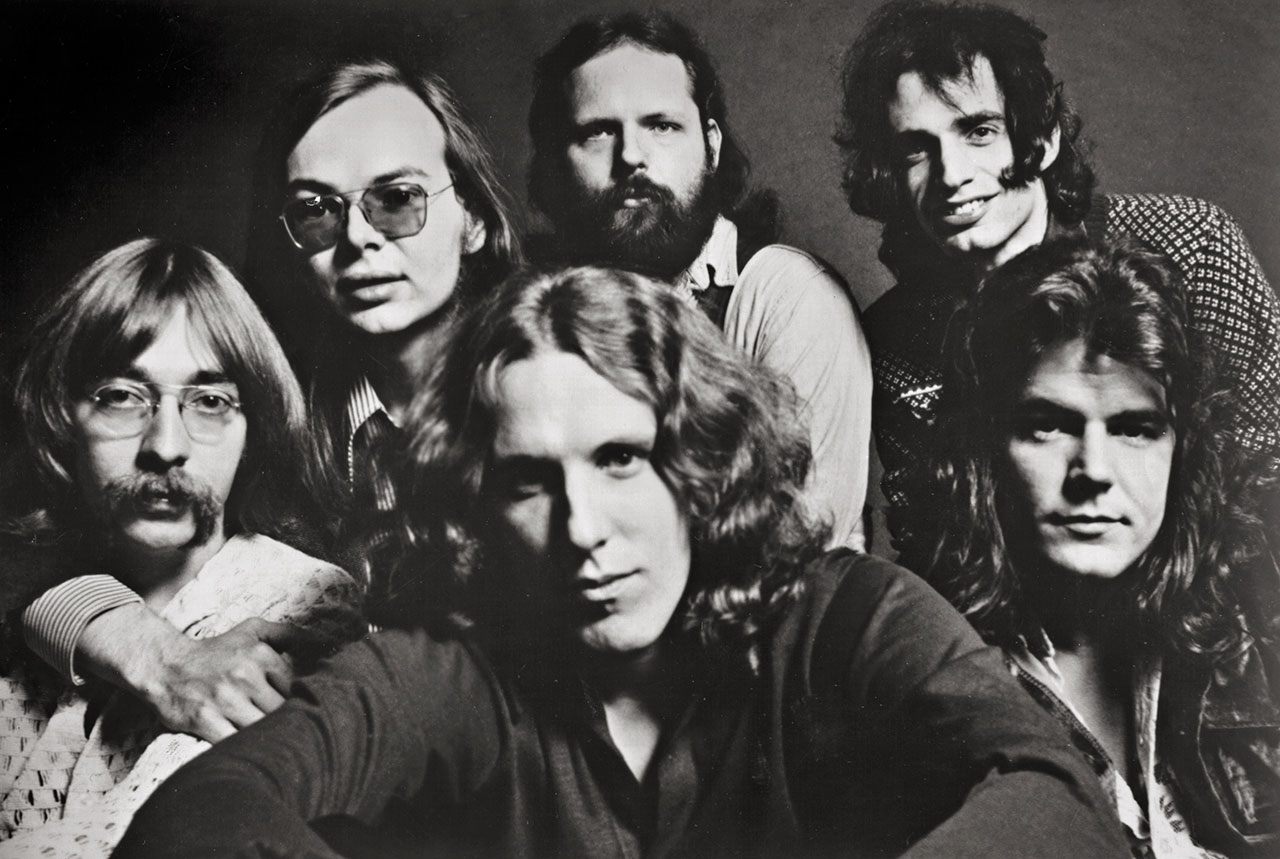

Their second album, Countdown To Ecstasy, was released in July 1973. Becker and Fagen revisited The Bard on the song My Old School, and hired guitar hero Rick Derringer to play the honking slide solo on Show Biz Kids. The album’s back cover bravely included a group shot. But the Dan, with their walrus ’taches and bib overalls, were unlikely to replace The Osmonds in the hearts of young America. The album was full of great songs, but it didn’t have a hit single. “That album was written hastily when we were on the road,” Fagen admitted later.

Out on the road, Steely Dan opened for The Kinks, Elton John and the James Gang. And Fagen hated every minute of it. Drummer Jim Hodder remembered Fagen having to take Valium just to get through a show: “He’d pace around the dressing room, the Valium would take effect, and right before we went on stage he’d have two shots of tequila.”

A schism developed between the largely abstemious Becker and Fagen and their bandmates, who merrily embraced all the narcotic and sexual perks of touring life. “I don’t like the jock atmosphere of the travelling rock’n’roll band,” Fagen complained. “It’s corny, it’s boring and it’s silly.”

The same divide continued during the making of Pretzel Logic, but for different reasons. Before the rest of Steely Dan reconvened at Village Recorders in October 1973, they were told that Becker and Fagen had hired session musicians to also play on the record.

Denny Dias wasn’t surprised. “I always thought Donald and Water were the band,” he said. But drummer Jim Hodder (who died in 1990) was shocked. Hodder was demoted to backing vocalist, while Jim Gordon (Eric Clapton/Joe Cocker) and teenage hotshot Jeff Porcaro (later of Toto) played the drums on Pretzel Logic. “I understand it now, but I resented it then,” Hodder said in 1985.

For Becker and Fagen, though, Steely Dan was still a work in progress. “We may have been typecast from our first album,” Fagen suggested. “But I don’t think I knew or anybody knew what kind of group that was.”

Additional personnel on Pretzel Logic included keyboard player Michael Omartian and backing singer (and future Eagles bassist/vocalist) Timothy B Schmit. Both recalled Becker and Fagen’s exacting standards.

“They strived for perfection, and both paid attention to every note and breath,” Schmit told Classic Rock. “I remember doing take after take on Pretzel Logic. Finally I went: “Yes! I got it!’ And they pressed the talk-back button and went: ‘That was great, really good… One more time.’ So I did it again.”

“Working with Steely Dan could hardly be considered ‘fun’,” said Michael Omartian. “But it was rewarding. You planned on long hours and not a lot of affirming moments.”

Omartian was due to get married in the middle of the sessions. After sharing a bottle of champagne with the band, he drove to Las Vegas for the wedding, but was back at Village Recorders in time for the next day’s session. “When [Becker and Fagen] were happy, you would pretty much hear the words: ‘We got the take,’ and that was it,” he said. “You would realise you did a good job when you got a call to do the next song.”

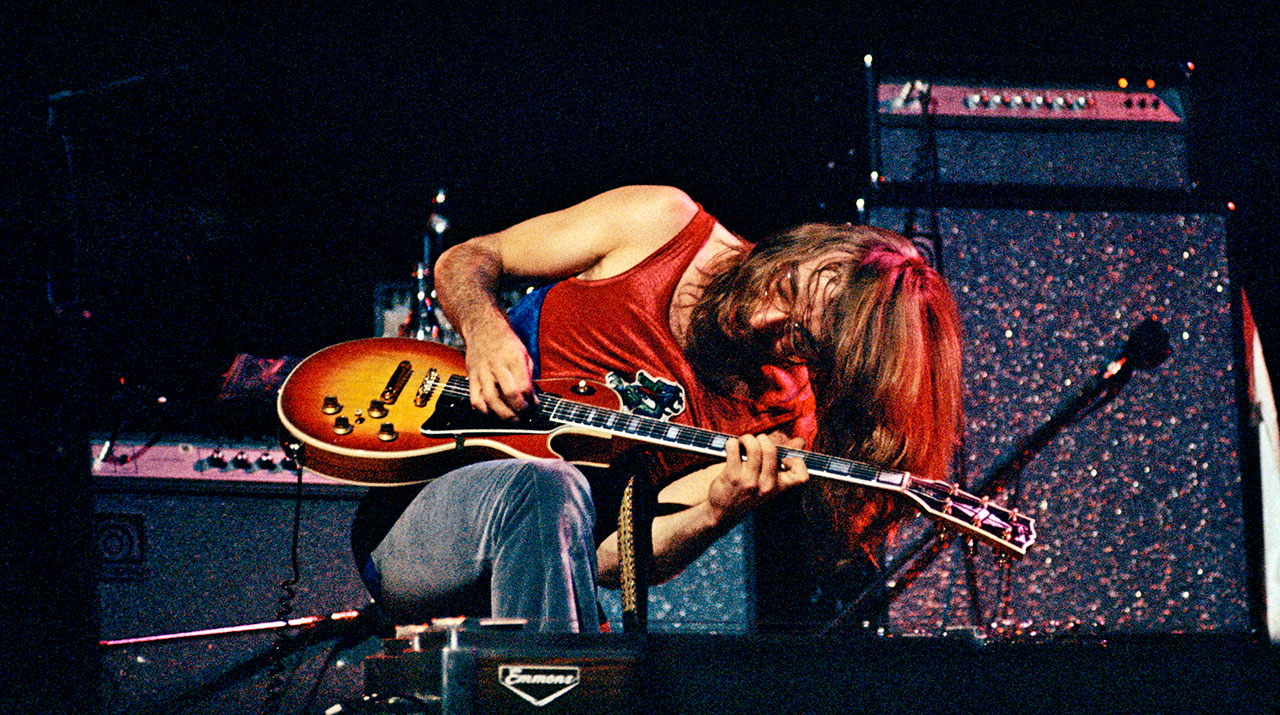

Becker and Fagen were just as tough on themselves. Becker usually delegated the solos to another guitarist, but was persuaded to play the one on Pretzel Logic’s title track. He spent an hour perfecting each bar. “Everything is flawed,” said Fagen. “The best you can hope for is the most precise playing that humans are capable of.”

Of Steely Dan’s three albums to that point, Pretzel Logic came the closest to meeting that expectation. To begin with there was Rikki Don’t Lose That Number, with Omartian’s syncopated opening piano figure, Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter’s measured guitar solo and Fagen’s glorious chord-change vocal: ‘But if you have a change of heart’. Near perfection, surely, in the album’s first 4:30 minutes.

So who was Rikki? Steely Dan never said. But the American writer and former Bard student Rikki Ducornet later outed herself, claiming a young Donald Fagen had passed her his phone number at a party. Although you still wonder if her story isn’t another Bard college in-joke to throw everyone off the scent.

Only Parker’s Band seemed to be about something tangible: jazz saxophonist Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker’s ensemble, with an allusion to its leader’s drug habits: ‘We will spend a dizzy weekend smacked out in a trance.’ The jazz homage continued with a cover of Louis Armstrong East St. Louis Toodle-Oo, on which a wah-wah guitar mimicked the muted trumpet on the original. Closing side one, it sounded like a piece of intermission music.

The rest of Pretzel Logic was filled with wonderful half-told stories. On the stately Any Major Dude Will Tell You, Fagen sung about ‘a squonk’s tears’, after a mythical animal in Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’s Book Of Imaginary Beings. (Genesis read the same book and wrote their song Squonk two years later.)

But who was Buzz, and was he ‘a fairy’ as suggested in the lyric to Through With Buzz? “It’s a song about a more or less platonic relationship between two young people,” Fagen explained. Although apparently, Fagen said, the male half began having sexual fantasies about his female friend. Elsewhere, the title track, a rare Steely Dan 12-bar blues, found its protagonist teleporting back in time to meet Napoleon and to experience ‘a travelling minstrel show’. And you could still hear the black-clad English Lit student Donald Fagen in Barrytown, a song that so impressed writer William Gibson that he named a city after it in his 1986 cyberpunk novel Count Zero.

What also amazes about the Pretzel Logic album now is how Becker and Fagen use their influences to such great and often unexpected effect. Night By Night, with its great filmic lyric (‘It’s a beggar’s life, said the queen of Spain…’), begins with blaring horns and a choppy funk rhythm like the soundtrack to a 70s blaxploitation movie. Closer Monkey In Your Soul suggests a Motown hit gone horribly, brilliantly wrong. The album is full of great musical anomalies: the sweeping strings on Through With Buzz; Steely Dan ‘doing’ The Byrds on With A Gun; and are those sleighbells on Charlie Freak?

Interviewed in 1977, Fagen said “there was a good year’s worth of introspective thinking involved” with any new Bob Dylan album. He could have been talking about Steely Dan. Even the front cover photo of Pretzel Logic, taken in snowy Central Park in New York invited speculation. Apparently there was an earlier version with a young vendor, who had spelt ‘pretzels’ correctly on his cart, but he wouldn’t sign a release form allowing ABC to use the picture, so the photo of an older ‘hot pretzle’ [sic] vendor, looking like a Mafia don in disguise, was used instead.

The critics adored Pretzel Logic; New Musical Express anointed it their Album Of The Year. More importantly, normal people bought it in droves, at least in the US where it reached No.8. In the UK it only just made the Top 40.

Steely Dan made their live UK debut that summer, at London’s Rainbow theatre. Apparently they spent five minutes tuning up before they played a note. “Don, baby, you ain’t as cool as you think,” finger-wagged one reviewer.

On July 5, 1974, Steely Dan played the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Only Becker and Fagen knew it would be Steely Dan’s last show (until 19 years later, it turned out). After the gig, some of the band spent the night dropping acid at Becker’s house. The following morning, as they slouched around in a post-LSD daze, Becker informed them that the group was no more. It was over. “We all busted our asses,” said Jim Hodder. “But it was those guys that were Steely Dan.”

After summer 1974, Fagen and Becker officially ‘became’ Steely Dan and retreated to their natural habitat: the studio. For future albums, including the exquisite The Royal Scam and Aja, they hired the cream of America’s session musicians to try to recreate the perfect sounds in their heads.

Right now, the late-sixty-something Becker and Fagen are back on the road. Steely Dan are finishing a nine-night residency in Las Vegas, smirkingly billed as Reelin’ In The Chips. A promotional photo shows them posing by a blackjack table, the spirit of The Bard still lurking behind their older, craggier eyes.

There hasn’t been a new Steely Dan album since 2003. In Las Vegas they’ve played the old songs, even the ones with “a horse’s head on every page”. After all, there are plenty of good ones to choose from. But still you wonder: did they ever find perfection? Maybe not. But on Pretzel Logic they certainly came close.