How Syd Barrett cast a spell that lasted throughout Pink Floyd's career

Pink Floyd are synonymous with Roger Waters and David Gilmour, but Syd Barrett remains the lost genius at the heart of the band

After their particularly acrimonious break up, The Eagles said they’d re-form when Hell froze over. So, Hell froze over. And it must have happened again for the Live 8 concert in July 2005, as the next most unlikely reunion took place: that of Roger Waters and the three-quarters of Pink Floyd who'd had the audacity to carry on without him.

But the real evidence of Hell’s temperature dropping well below zero would have been if Pink Floyd’s reclusive originator had stepped from the shadows, dusted off his guitar and joined his former bandmates on the Hyde Park stage. It’s often forgotten, but Pink Floyd is neither Roger Waters’ nor David Gilmour’s band. It’s Syd Barrett’s.

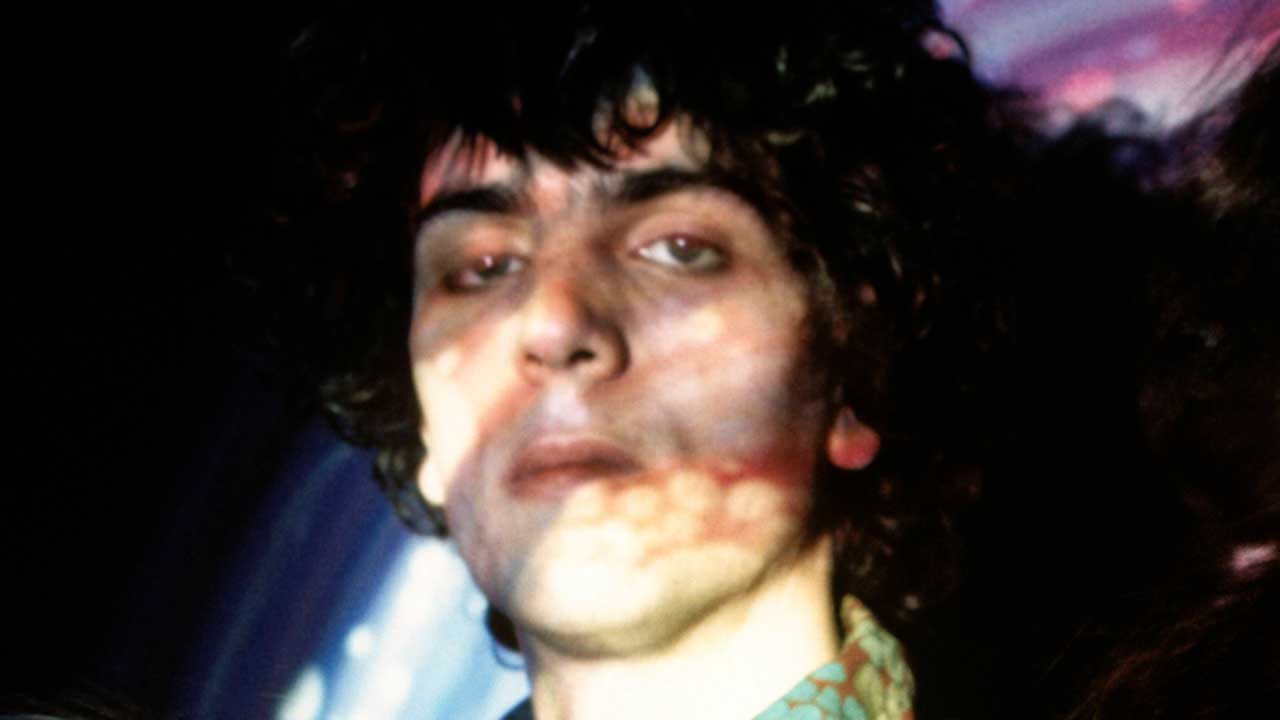

Sometimes it seems that Syd has been all but written out of Floyd’s history, the bitter split of Waters and Gilmour and the phenomenal success of post-Barrett albums like The Dark Side Of The Moon and The Wall overshadowing the humble beginnings of a psychedelic rock combo dreamt up by art student Barrett. For years, Syd appeared to be little more than a footnote: the guy who was once in Floyd, flipped out, left the band and the music biz, then led a semi-reclusive life in Cambridge before quietly passing away a year after Live 8.

But if you consider it closely, you’ll see that without Syd there would have been no Pink Floyd as we know it – his profound magic casting a spell that pervades the myth and musical output of the Floyd throughout their entire career.

In 1965 Syd was studying fine art at Camberwell in London when he hooked up with fellow students Roger Waters, Rick Wright and Nick Mason (at this point David Gilmour was just a friend from home in Cambridge with whom Syd had traded guitar riffs). Syd commenced work developing his sound, and thus The Pink Floyd was born.

Syd had a vision for his musical endeavours, an idea that stepped beyond the three-minute pop songs that were chart fodder of the time. He saw his band not only as a musical entity, but rather as an extension of his creative and artistic endeavours. Barrett was never shy about admitting that music wasn’t his primary obsession.

“I didn’t mean to play forever,” he said. “It was painting that brought me here to art school. I always enjoyed that much more…”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Syd’s somewhat rudimentary guitar playing meant that he had to find other ways to express his musical vision. His playing was ramshackle, using wah-wah, feedback and discordant passages to create a sonic palette that was brand new to the music listeners of the mid-60s.

“The Floyd’s music arose out of playing together; we didn’t set out to do anything new,” Barrett reflected in 1971. “We worked up to See Emily Play and so on quite naturally from the Rolling Stones numbers we used to play. None of us advocated doing anything more eccentric.”

It was Syd who first took the tales of superficially everyday folk and translated them into quirky songscapes. But they were stories with an edge. Floyd’s early single, the aforementioned See Emily Play, dealt with madness. Lyrically Barrett was preoccupied with the mind and all its frailties, the chorus illustrating how close the central figure is to losing the plot: ‘There is no other day/Let’s try it another way/You’ll lose your mind and play/Free games for May/See Emily play’.

The themes of despair and a mind teetering on the edge of oblivion would become the blueprint that would characterise the rest of Floyd’s material, long after Barrett had left the band. From Dark Side’s tirade ‘I’ve been mad for fucking years, absolutely years, been over the edge for yonks…’ to the steady mental disintegration of Pink (the central character in The Wall), insanity was never too far away.

It’s an oft-told story concerning Syd’s reappearance – virtually unrecognisable, balding and overweight – in the studio as the band recorded Shine On You Crazy Diamond, Floyd’s homage to the man who had directed their career.

Even the song that paid tribute to Syd utilised the word ‘crazy’, albeit in an affectionate rather than abusive manner. ‘Shine on you crazy diamond/Well you wore out your welcome with random precision, rode on the steel breeze/Come on you raver, you seer of visions, come on you painter, you piper, you prisoner, and shine.’

Before Syd finally quit his own band in April 1968 following his own mental decline after prolonged LSD experimentation, it had been suggested that he would carry on working with Pink Floyd as a songwriter and possibly a studio musician. That was never to be, but whether Gilmour and Waters explicitly acknowledged it or not, his influence on the band has continued.

It wasn’t just Barrett’s obsession with the darker sides of the human psyche that would go on to characterise Floyd’s work without him. The spectacular light shows and theatricality were more than hinted at when he was in the band. Floyd’s early gigs utilised oil-slide projection and strobe-effect lighting to further enhance the music.

“Really,” Barrett told the Melody Maker in 1967, “we have only started to scrape the surface of effects, and ideas of lights and music combined; we think music and lights are part of the same scene, one enhances and adds to the other. But in future, groups are going to have to offer much more than just a pop show. They’ll have to offer a well-presented theatre show.”

And as we know. Pink Floyd took him at his word. Perhaps Roger Waters sums it up best.

“Syd is a genius,” he said after the Floyd split.

And there’s a very fine line between genius and madness.

Classic Rock editor Siân has worked on the magazine for longer than she cares to discuss, and prior to that was deputy editor of Total Guitar. During that time, she’s had the chance to interview artists such as Brian May, Slash, Jeff Beck, James Hetfield, Sammy Hagar, Alice Cooper, Manic Street Preachers and countless more. She has hosted The Classic Rock Magazine Show on both TotalRock and TeamRock radio, contributed to CR’s The 20 Million Club podcast and has also had bylines in Metal Hammer, Guitarist, Total Film, Cult TV and more. When not listening to, playing, thinking or writing about music, she can be found getting increasingly more depressed about the state of the Welsh national rugby team and her beloved Pittsburgh Steelers.