It’s April 1974 and Melody Maker can hardly believe the news: weirdo German eggheads Tangerine Dream are in the official Top 20 Album Chart with a strange piece of instrumental work called Phaedra. Its placing is even higher in the Maker’s own listings.

Not only are there no vocals, there are no hooks and precious little guitar. Instead there are Moogs, hulking great synths and 11-minute drones with titles like Mysterious Semblance At The Strand Of Nightmares. Affronted by such flagrant disregard for rock’n’roll protocol, the music weekly duly lays in.

“As far as I’m concerned,” wrote critic Steve Lake, “Phaedra is gutless and spineless, devoid of inspiration, imagination or plain old-fashioned funk. But maybe a few hundred thousand potential record buyers can’t be wrong.” He went on to compare Tangerine Dream’s history to “a B-Movie script. It’s all the brainchild of Edgar Froese, a failed heavy guitarist.”

Such journalistic venom was common. It was, lest we forget, the era of David Essex, ABBA and The Wombles. Alice Cooper was still considered edgy. To most ears, the music of Tangerine Dream seemed as forbiddingly foreign as it was unfathomable. Which is all well and good when nobody’s buying your records, but now they were a success.

“We didn’t have a great open-minded crowd in our early days,” Froese tells Prog today. “There was a rejection attitude all the way through ‘til we reached Number 10 with Phaedra on the Melody Maker charts. I remember the first ever LP review in Britain was half a page in Melody Maker. Steve Lake opened the review with the headline ‘Eat more shit – 100,000 flies can’t be wrong.’ But that was our breakthrough into the international market, even if Lake would have done everything to protect the market from the ‘German knob-turners’. He hated us.”

Fellow band member Peter Baumann, on the line from his home in California, recalls that same review. “I remember that ‘100,000 flies’ line well,” he says with a faint chuckle. “When Virgin picked up Phaedra we had chart success. But there were obviously still a lot of people saying, ‘What the hell is that?’”

Tangerine Dream were already used to all that though. They had started out in Berlin in 1967, when Froese corralled some fellow Academy Of Arts students into forming an experimental rock band to play parties and happenings. They became known in Berlin underground circles, once performing for German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys. Salvador Dalí saw them too, inviting them over to play at his villa in Cadaques, Spain. He was intrigued by what he called this “rotten religious music”. Froese and Dalí became friends for a time, though their artistic and political beliefs weren’t always mutually sympathetic. “During one of our longer conversations in his olive garden in Cadaques,” explains Froese, “Dalí was saying that he decided to be against everything the public like and adore. So if the masses like democracy he stands for dictatorship and the other way round. ‘If you’re a divine individual, you have to think and behave outside every rule the Bourgeoisie tries to dictate,’ he explained in his mixture of Catalan, English and French.

“As an artist and cosmopolitan being, he was absolutely fascinating. On August 8 1967, we performed The Resurrection of Rotten Christianity – Music for a Sculpture. It took place at a happening in the olive garden behind his home and atelie in front of a sculpture built out of Coca-Cola cans, some flotsam he found in the sea and olive tree branches.”

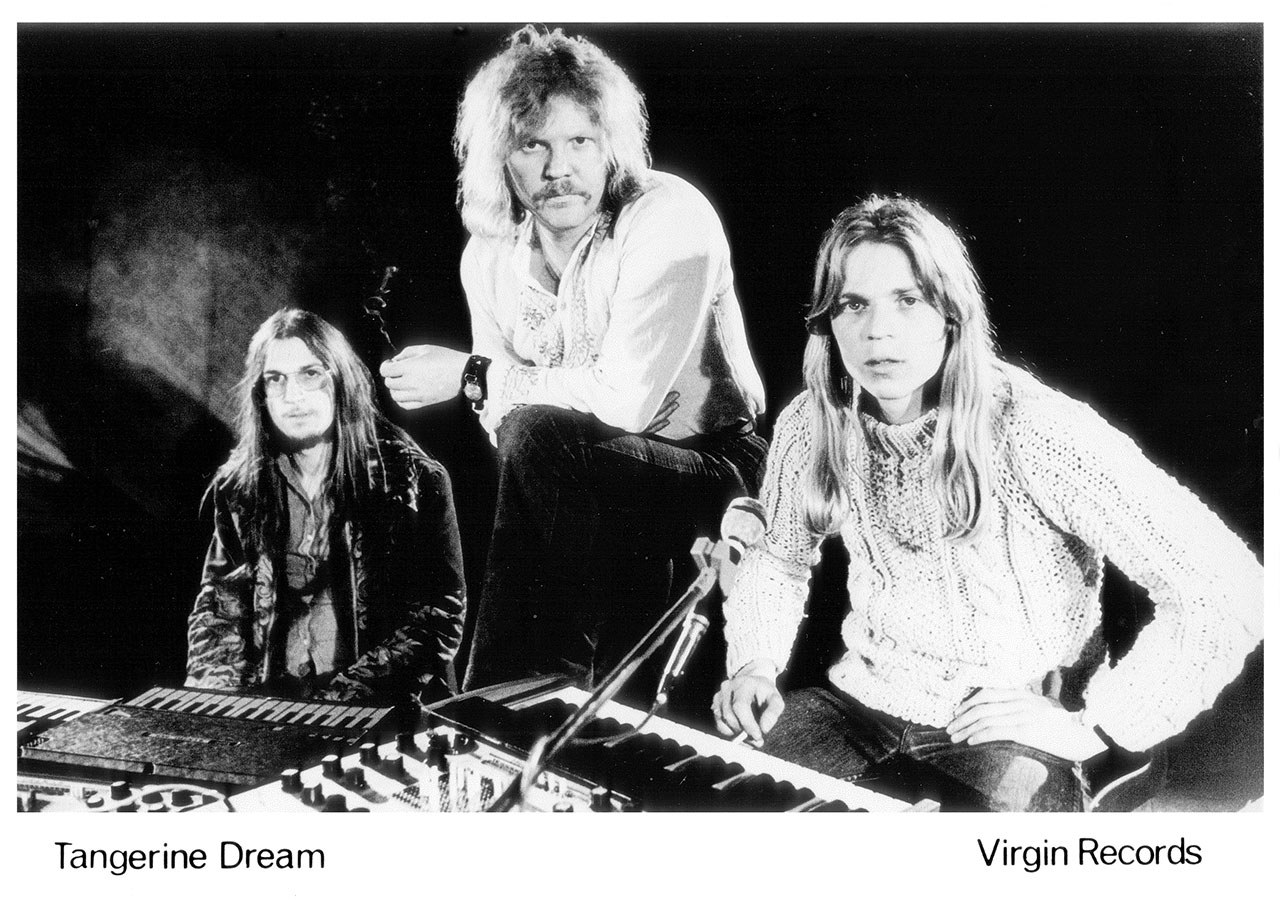

Froese readily acknowledges the influence of Dalí on his music. Suddenly, everything was possible. He decided to “do the same thing as he did in painting, in music.” Tangerine Dream’s debut LP, Electronic Meditation, arrived in 1970. Froese’s partners at that point were Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler, who joined him in freeform experiments with tape collage, percussion and rock guitar. When his bandmates left for pastures new, Froese brought in fresh blood, including drummer, flautist and synth player Christopher Franke. This marked a crucial shift in emphasis. The following year’s Alpha Centauri was more reliant on electronica and keyboards, prompting Froese to dub this new adventure in sound ‘kosmische musik’. The band took on its definitive form later that year with the arrival of 18-year-old Baumann.

It was a time of sweeping innovation in the German music scene. There was the esoteric, through-a-hedge-backwards rock of Can and Faust, the post-hippie imaginings of Amon Düül, the gliding electro pulse of Kraftwerk and the cosmic wanderlust of Ash Ra Tempel, to name but a few. Did Tangerine Dream feel part of all that? “Not at all,” says Baumann. “The Amon Düül guys and the Kraftwerk guys felt like they were all isolated. We were totally self-absorbed. There wasn’t much hanging out at all.”

Froese has a slightly different angle, suggesting that, even among the marginal so-called ‘krautrock’ clique, Tangerine Dream were outsiders: “There was a strong musical community in Germany during that period, but we weren’t a part of it. We couldn’t even invite others for a jam session, or jam around with others, because when we were switching on the knobs everybody became very suspicious. It was as if we were just starting a rocket for a one-way space exploration. There was one experience during a gig in Berlin with Amon Düül II. Before we started I gave the keynote of our philosophy by saying: ‘Dear friends, it’s December 6 1971 at 8pm in the city of West Berlin. Please be kind enough to improvise with us in a way that never can be repeated.’ They stared at me as if I had taken my head off and put it under my arm.”

But Tangerine Dream didn’t need anyone’s blessing. “It was strange,” recalls Baumann. “When the three of us were together, it felt like there was a fourth person there, a fourth energy. It was unique. We felt like we didn’t have personal profiles, we were a unit. We’d get together and stay up all night and listen to music – from Italian classical music to the first Pink Floyd record. We never watched TV; we’d just hang out, smoke a joint and listen to music until the early hours of the morning.”

By 1973 they had a strong cult following. Their music was now a pioneering mix of synthetic textures and ambient moods. Their prime European stronghold was the UK, where John Peel had declared Atem, the Dream’s fourth LP, his album of the year. Richard Branson’s fledgling Virgin label – then specialising in imports from

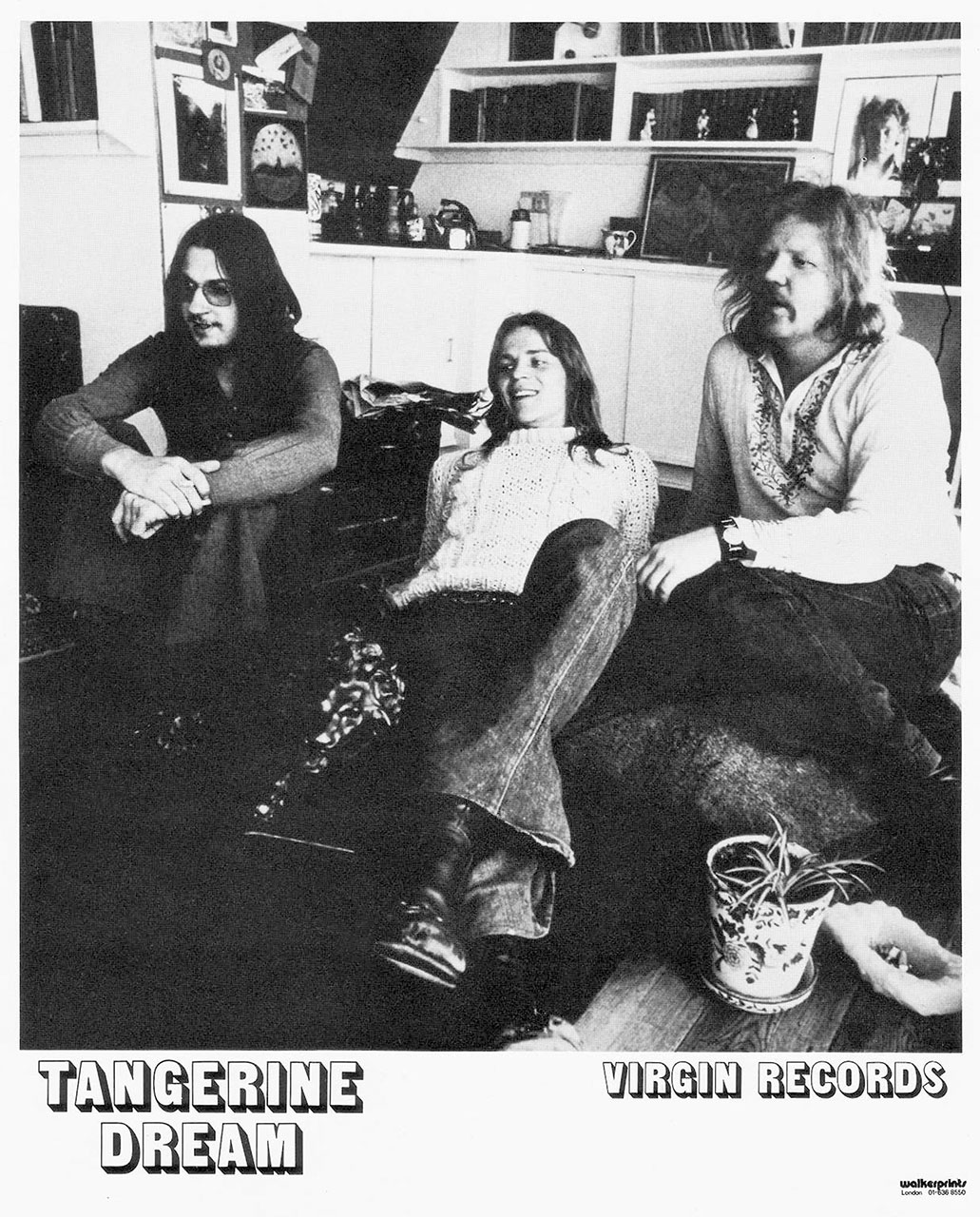

the continent – sold more than 15,000 Tangerine Dream albums, largely on the strength of Peel’s repeated airplay. It swiftly led to the offer of a record contract, with Froese, Franke and Baumann inking the deal on the stairs of Branson’s Virgin Records shop in Notting Hill. It was the beginning of a fruitful, if slightly unconventional, relationship. The courtship involved games of chess on Branson’s houseboat (“he lost three and won two against me”, says Froese) and, in Baumann’s words, “chasing girls and playing tennis at his house. It was hot, so we’d just play in our underwear.”

Then there was the time the band went to renegotiate their deal. “We went to

a building in Vernon Yard, just off Portobello Road,” remembers Baumann. “And Richard Branson was in the first office. We negotiated our contract, then suddenly he jumped out of the window. Somewhere he managed to find crutches and came back walking on them, pretending he was injured, that it was all over and he would have to close the offices. That he just couldn’t deal with us anymore. We had a strange reputation; we really were seen as ‘the Krauts’ at Virgin – we made bizarre music and had strange accents. We were like the weird kids on the block. Quite frankly, Richard didn’t have a clue why anyone would want to listen to our music. He wasn’t really a music fan. He liked the noise and the idea of doing big things, but he didn’t have the nerve or the patience to sit down and listen to our records.”

It was nevertheless a successful time for both parties. Phaedra was groundbreaking in its ambition and scope, the trio using Moogs and sequencers to sculpt a symphonic world of cosmic trance. “It goes back to my early years as a pupil of classical music, when I realised that everything in musical structure is bass-oriented,” explains Froese. “We were the first band to ever use the Moog modular system as

a standalone sequencer. The programming of those [Phaedra] sequences was time-consuming but it gave the endless freedom to improvise on top of those basslines. Without exaggerating our musical capabilities, we were very much ahead of our time.”

1975’s pulsating Rubycon offered much of the same, albeit with more of a groove. That too was a commercial success, peaking at Number 12 in the UK album chart. But live gigs were a different matter. Tangerine Dream would later incorporate laser projections and the odd burst of pyrotechnics into their shows, but those early 70s audiences were often baffled by the band’s improvised musical excursions into anti-rock. The faithful lapped it up, of course, but there were also frequent walkouts and abuse.

“We were never physically attacked, but we were attacked mentally and emotionally very often,” says Froese. “The mass audience was and still is kind of an unconscious animal who never would leave home without a guaranteed safe return. As far as our early performances are concerned, the stage after a performance looked like a weekly vegetable market rather than a concert stage. People had fun throwing bad apples and bananas towards our early electronic gear and were laughing their asses off. You need a lot of trust in your beliefs and even more patience that one day it will be over. And I was right, fortunately. The worst and most intolerant country was, and still is, my homeland in Germany.”

The classic Tangerine Dreamteam lasted until 1977, when Baumann left the band for a solo career. “When you’ve had a good run, you sense that it’s coming to some sort of end,” he says. “It just felt like it wasn’t as much fun anymore. And I think Edgar wanted to go in some other direction.”

Froese, for his part, states that “I had to ask Peter Baumann to leave the band after he had performed a very offensive and egocentric affair about developing his solo career after our two US tours in 1977. Also my relationship with Christopher Franke was quite strained.”

When Franke finally quit 10 years later, Froese pressed on, releasing a dizzying array of solo albums and soundtracks alongside stewardship of Tangerine Dream, where he remains today. But it’s those Virgin albums of the 70s – reissued now by EMI – that showcase the band at its peak.

“We were always on the lookout for anything that made noise,” reflects Baumann. “I mean, I was crushing glasses against the wall and recording that before the synthesizer came along. It was all about sound and exploration.”

This article originally appeared in issue 14 of Prog Magazine.