Roland Orzabal is talking about his fondness for Genesis and King Crimson. “I was a big early Genesis fan – Foxtrot particularly. And Genesis Live was great. I loved King Crimson – especially Discipline, if you can call that prog? It depends what you define as prog. There used to be a lot of reverse snobbery – Genesis came from a public school so therefore they can’t be any good, they’re ‘not like us’. Okay, punk rock was a jolt and a Copernican inversion. We went from having long hair and playing eight-minute guitar solos in our teenage band to all of a sudden covering The Damned! Fashion is incredibly powerful in music, in the zeitgeist. You got to a certain point in the late 70s where you could not wear flares any more. And my platform shoes had to go. It was horrendous!”

After chuckling at the memories of his teenage wardrobe choices, and recalling the influence of Robert Wyatt and Pink Floyd, Orzabal becomes philosophical again.

“That’s the great thing about time passing. You see everything in its place, era-based: it’s just fantastic. Yes, you can like both the Sex Pistols and Genesis – of course you can!”

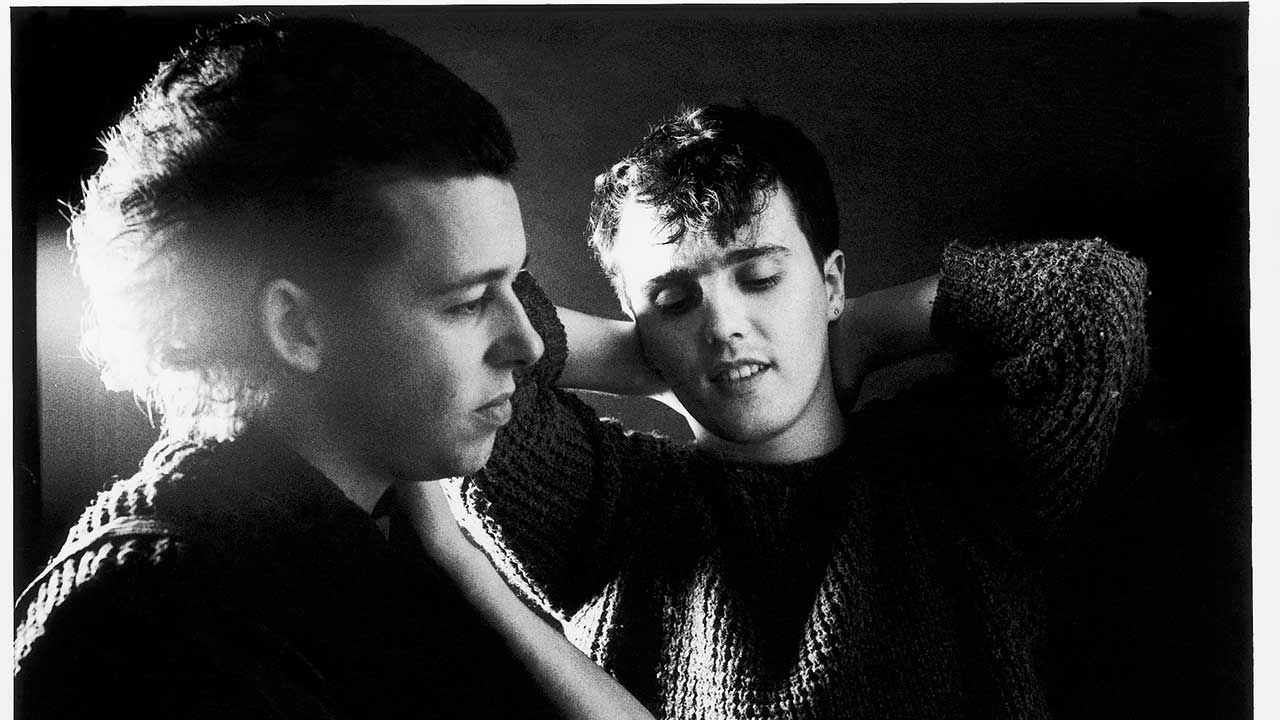

Tears For Fears’ first three albums lit up the 80s with an extraordinary range of genre straddling, and while they delivered a stream of odd, epic and insanely catchy singles, they were much, much more than the ‘synth-pop duo’ they were sometimes tagged as. 1983’s The Hurting, inspired by their fascination with primal therapy, was existential doom with hooks. 1985’s multi-platinum Songs From The Big Chair ruled the world, let it all out and was head over heels with invention. Yet perhaps The Seeds Of Love, flowering in 1989, was their most ambitious of all.

It took around four years and a million pounds to make, and effectively broke up the band – Orzabal continued with the name until he and Curt Smith reconciled in the early 21st century. It incorporated Beatles-esque psychedelia, pop, prog, soul, jazz, socialism and feminism, somehow stirring all these elements into an intoxicating cauldron of colour and catalysts. Now reissued with a bundle of diverse demos and out-takes (which reveal how varied the band’s playbook was), it remains a dazzling prism of sounds and styles.

It wasn’t easy to create. Whereas Tears For Fears had knocked it out of the park with their second album, this was a case of ‘the difficult third’.

“It’s nuts,” muses Orzabal. “I’m 59 now, and we’re talking about something I made in my late 20s. I remember it very well. The massive success of …Big Chair, and all the touring that ensued, created a massive hangover for Curt and me. If we hadn’t been pushed so hard to keep promoting, we’d have been better off. Then again, it was during those tours that we found ourselves in a Kansas hotel bar on a Sunday night and came across Oleta Adams playing this incredible gig. And she was a major factor in our making The Seeds Of Love such a special record. It defies genre; it surprised people who’d labelled us as one thing – it’s everything.”

Did they intentionally move away from the perceived notions of ‘typical 80s pop’ and electronica to work on something more organic?

“Well, when we were in our early 20s we could watch Top Of The Pops and see people who looked like us, the same age, and we’d aspire to that. But having had all that huge commercial success, it was like: ‘Okay, been there, done that, what do we do next?’ The music scene in England was becoming more overtly pop: it was the days of Stock, Aitken and Waterman and I couldn’t listen to Radio 1 any more. Chris Hughes (who’d been our producer) had always been introducing us to 70s music, and indeed I’d grown up with it. Curt and I had a shared affection for early Blue Öyster Cult. So we’d hear Steely Dan, Little Feat, and think: we don’t want to compete with our peers anymore, we want to compete with those guys! With the classic artists. So that’s what we set out to do. It just took a long time…”

The album moved through a Snakes & Ladders board of sessions, producers, musicians and paradigm shifts. “And there were a lot of things going on, for me… personal growth.” They’d started the band to “get rich, get famous and get therapy”, inspired by the writings of Arthur Janov. Orzabal now finally started primal therapy, having moved to London with his wife. “The career went on the back burner, as I sort of dealt with my demons.” Two or three times a week he’d take the 25-minute walk from his new home in Belsize Park to therapy in Tufnell Park, and back, and “the songs emerged, on those walks”. He wrote and recorded in his upstairs studio, and “it was very peaceful”.

“And yet when you’re in London, you’re a little more plugged in. My antennae were certainly up. There was a change happening, and it ended up with the rave scene and the second ‘summer of love’. Part of me was tuning into that. I mean, I grew my hair, got a bit hippie-dippy! ‘I love a sunflower’ was something I saw graffitied on the fence opposite my house.”

Magical Mystery Tour seems to have played a part in the album’s DNA too, even though Beatlemania had all but bitten the dust during that era.

“Yes, it came back in the 90s, didn’t it? One of my favourite songs ever is I Am The Walrus, and sure, we’d mapped that out, including the tempo, when recording Sowing The Seeds Of Love. With a dash of Hello Goodbye.”

At the same time, they tapped into the topical as they lambasted ‘the politics of greed’.

“Exactly. I couldn’t bear Thatcher. Couldn’t stand her. I was becoming more politically aware, moving away from psychology. I started reading up on Marxism. It was a revelation.”

Orzabal takes it as a badge of honour when Prog asks if he was a perfectionist. “Still am, always was,” he replies.

As the team probed and prodded for his new direction, there were stalled stints with Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley and other faces in the producer’s big chair. “Chris Hughes, bless him – we worked with him again, fired him, hired him again. Everything got difficult for a while. Nothing was ever like: ‘Let’s just do this, record this three and a half minute song, nothing wrong with it, come on.’ No. Because of the ‘magnificence’ of …Big Chair, it was almost like we had to one-up ourselves. So Chris would take tracks apart and put in a middle-75 of backwards guitar, and it was: ‘Okay, Pink Floyd, here we come!’ Very prog, ha ha! But the thing is you can have a perfect track which lacks soul. For me, it had to have life. So, while there were arguments about the running order etcetera, for me the album wasn’t difficult, it was a joy. I am so proud of Badman’s Song, and what we did with that. Taking all the best bits from God knows how many takes – 30 or 40 – and ending up with all this amazing improvisation. I know the band got very pissed off at me at times, but I’m glad we did it, because it’s now there for posterity.”

Is Woman In Chains, sung as a duet by Orzabal and Adams, the feminist anthem it’s usually read as?

“Um… it was really about my mother. At one point in her life she was a stripper. My father and she ran an entertainment agency from a council house in Portsmouth. So she would go out to strip, and my father would send a driver out with her to spy on her. If she talked to another man, when she came back he would beat her up.

So it’s about domestic abuse.”

The conversation understandably takes a few detours before Prog gets back to the music, and Phil Collins’ appearance on that song.

“We did try to get him to do a big In The Air Tonight kind of thing,” smiles Roland, “but he was very reluctant to do so. So we hacked together that drum fill…” Smith had asked him if he’d play on the track, and how many days he’d need in the studio. Phil answered that he’d come in at lunchtime and be home in time for tea, and was.

Smith, for his part, explains Orzabal, became a “big picture figure” on the album, as “there were so many ‘details men’ already: he’d not get too involved in the nitty-gritty, but come in with an overview.”

More recently, Steven Wilson engaged with both nitty-gritty and overview with his mix for this release. “He’s done a remarkable job. He’s a bit of a genius, that guy.”

Ultimately though, The Seeds Of Love, and Tears For Fears’ template-smashing new vision, was more Roland Orzabal’s baby than anyone else’s. “I was just following the muse. Because if you don’t, you’re damned. And I’m glad I did. Because what you create is interwoven with life. That’s the incredible thing about art. It’s representing the changes within you, as you grow and evolve. My only regret is that perhaps Curt and I didn’t realise the magnitude of what we’d achieved together in that era. And we didn’t realise it wasn’t over. Had we patched things up back then, we could’ve made some more good records. But we were so young, y’know? Suddenly we became huge, with all the trappings and excesses that come with that. I’m thinking about my sons now, 25 and 28, and – ha! – ‘Well, this is what we did in our 20s…’”

In the present day, the reunited Tears For Fears have been working on their next album for seven years. A mere seven? “Exactly! We’re going to top The Seeds Of Love! [Laughs] If they allow me into America, because I need to be in the same room as Curt, we’re hoping to finish it this year.

“Look, we knew we were leaving a lot of people behind with The Seeds Of Love. And we were happy to do so. There is no other band that could’ve made that record.”